Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Sunanda Creagh, Head of Digital Storytelling

What do you need to know about COVID-19 and coronavirus? We asked our readers for their top questions and sought answers from two of Australia’s leading virus and vaccine experts.

Today’s podcast episode features Professor Michael Wallach and Dr Lisa Sedger – both from the School of Life Sciences at the University of Technology, Sydney – answering questions from you, our readers. An edited transcript is below.

And if you have any questions yourself, please add them to the comments below.

New to podcasts?

Everything you need to know about how to listen to a podcast is here.

Transcript

Sunanda Creagh: Hi, I’m Sunanda Creagh. I’m the Digital Storytelling editor at The Conversation, and I’m here today with two of Australia’s leading researchers on viruses and vaccines.

Lisa Sedger: Hi, my name’s Lisa Sedger. I’m an academic virologist at the University of Technology Sydney. And I do research on novel anti-viral agents and teach virology.

Michael Wallach: I’m Professor Michael Wallach, the Associate Head of School for the School of Life Science (at the University of Technology Sydney) and my expertise in the area of development of vaccines.

Sunanda Creagh: And today, we’re asking these researchers to answer questions about coronavirus and COVID-19 from you guys, our readers and our audience. We’re going to kick it off with Dr. Sedger. Adam would like to know: how long can this virus survive in various temperatures on a surface, say, a door handle or a counter at a public place?

Lisa Sedger: Oh, well, that’s an interesting question, because we hear a variety of answers. Some people say that these types of envelope viruses can exist for two to three days, but it really depends on the amount of moisture and humidity and what happens on that surface afterwards, whether it’s wiped off or something. So potentially for longer than that, potentially up to a week. But with cleaning and disinfectants, etc, not very long.

Sunanda Creagh: And what’s an envelope virus?

Lisa Sedger: Well, viruses are basically nucleic acid. So DNA like is in all of the cells in our body or RNA. And then they have a protein coat and then outside of that they have an envelope that’s made of lipids. So it’s just an outer layer of the virus. And if it’s made of lipids, you can imagine any kind of detergent like when you’re doing your dishes, disrupts all the lipids in the fat. That’s how you get all the grease off your plates. Right? So any detergent like that will disrupt the envelope of the virus and make it non-infective. So cleaning surfaces is a good way to try and eliminate an infective virus particle from, for example, door handles, surfaces, et cetera.

Sunanda Creagh: And Professor Wallach, Paul would like to know: should people cancel travel plans given that this virus is already here? Does travelling make the spread worse? And that’s international travel or domestic travel.

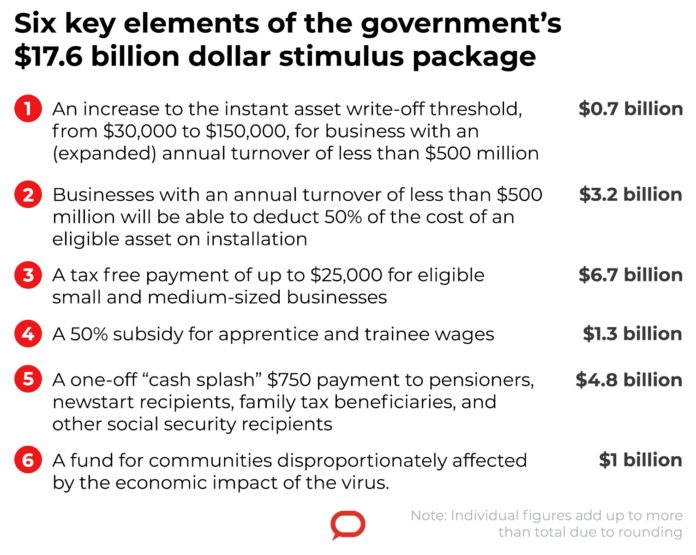

Michael Wallach: So this question has come up to many different governments from around the world who’ve reacted very differently. Australia’s been very strategic in banning travel to certain places. And of course, those places you would not want to travel to at the time when there’s an outbreak like China, Italy, Iran, etc.. I was also asked the question on ABC Tasmania: should the Tasmanians restrict domestic travel to Tasmania? At the time, they had a single case. And I said to them, if you have one case, you most likely have more. You will not prevent the entry of the virus into Tasmania. But what restricting travel can do is restrict the number of people who are seeding that area with virus and make it more manageable. So it’s a question of timing. As I was saying to you earlier, the cost-benefit of closing off travel has to be weighed very carefully because the economic impacts are very great. So I think it’s a case by case basis. Ultimately, the planet is now seeded. And we’re moving into the stage of exponential growth and that it will affect travel very severely, where in all likelihood, travel will be very much curtailed now.

Sunanda Creagh: And this question’s from our reader, David. He wants to know: with the flu killing more people each year than coronavirus and mostly the same demographic, why is this outbreak receiving so much attention? Can’t we just catch the flu just as easily without cancelling events and travel plans?

Lisa Sedger: Yes, and I understand the question. Flu exists. We get it seasonally every year and then we get pandemic flu. And yes, people do die from influenza. I think it was 16,000 people in the US died last US winter. But the issue with this virus is that we don’t yet know how to treat it particularly well. We’re trialling anti-viral drugs in China at the very moment. There’s clinical trials on experimental drugs. There’s drugs that doctors are using. But until that data comes in and we actually know what regime of anti-viral drugs (are best) to use, then we don’t really yet know how to treat it with anti-viral drugs. The other thing is with flu, we have a vaccine. People can take the vaccine. Somebody gets sick in their family, the other family members can take the vaccine and prevent the spread of the virus. So the difference is with flu, we have ways to control it. We know about the disease. We know how it presents. This virus, we’re still understanding the clinical presentation and in different cohorts. So different age groups, different countries, different situations, we’re still understanding the symptoms. And we don’t yet fully know how to control it by antivirals. And we don’t have a vaccine yet.

Michael Wallach: Can I just add to that a bit? I think one of the reasons we’re being so careful is when it broke and Wuhan, at the beginning the mortality rate was extremely high. And with related viruses like SARS, and MERS that went as high as 35%, whereas flu mortality rates is usually around 0.1%. So it was that very high mortality rate that gave a real shock. Had it continued, it would have been devastating. We’re very fortunate that now we see it dropping down to the 2 to 3% level and some say much lower.

Lisa Sedger: And we also know now that some people get COVID, have very minimal symptoms and almost don’t even know that they’ve been sick. So I think that fear and anxiety, in that sense, is lowering.

Sunanda Creagh: And Molly wants to know: how far off is a vaccine?

Michael Wallach: So, we are working on vaccines in Australia. The group in Melbourne was the first to be able to isolate and grow the virus. And I’ve been in touch with them, in fact, this morning. We’re working collaboratively nationally as well as internationally, collaborating with people at Stanford Medical School who through Stanford, in collaborations we have with them, we have worldwide about 15 vaccine projects going, plus all sorts of industry companies are aiming to make vaccines. In fact, one company in Israel early on announced that they believe that they can get to a vaccine within a few weeks. The problem with the vaccine is you may produce it even quickly, but it’s testing it and making sure that it’s actually going to help. There’s a fear, with COVID-19, that if it is not formulated correctly, to make a long story short, it can actually exacerbate the disease. So everyone has to take it slowly and carefully so that we don’t actually cause more problems than we currently have. But I’m optimistic and believe that we’ll get there. The WHO declared it would take 18 months. I would like to present a more optimistic view, not based on anything that substantial, but I think we can do better than that. And it is a great learning curve for the next time this happens.

Lisa Sedger: Can I make a comment on that, too? Recently, we’ve just seen Africa experience a very significant outbreak of Ebola virus, and there’s been an experimental vaccine that’s been administered that has largely controlled that outbreak. I think the people working in vaccines and the people who do the safety and efficacy studies, we’ve learnt a lot from how to administer vaccines, how to get the data we need to show safety more quickly than we might have in the past. So in the sense we’ve learnt, we’re learning lessons constantly from viral outbreaks. It might not be the same virus, might not be the same country, even the same continent. But we’re learning how to do these things more efficiently and more quickly. And always the issue is weighing up safety versus the ethics of the need to administer all get it, get the drug out there as quickly as possible.

Sunanda Creagh: This reader asks: isn’t lining up at fever clinics for tests just going to spread it even more?

Michael Wallach: So for sure, the way in which people are processed at clinics is crucial and the minimal distance you should keep from a person who’s infected is, according again to the WHO, is one metre. So the clinics have to ensure that spread is minimised, not only spread between people waiting in line, but to the health workers themselves. We’ve had real problems for health workers in China. Several died. And we face that problem here. One of the things we have to do is ensure that we protect our health workers because otherwise they’re not going to want to go in and actually see the patients. Unfortunately, masks alone do not work. We can’t rely on them. So it’s a problem. In Israel, for example, testing for COVID-19, takes place in one’s home. An ambulance pulls up and takes the swab and then takes it to the lab. That actually would be the ideal approach. True, the ambulance services in Israel now are swamped and having great difficulty in coping. But as much as we can keep people separated from each other when they’re infected, it’s crucial for the success of any campaign.

Sunanda Creagh: And these questions from Jake. He wants to know for people like myself living in Victoria. How likely is it that we can catch the virus and is hand-washing really the only thing we can be doing to protect ourselves?

Lisa Sedger: I think we now know that the virus is definitely in Australia. If you go to the New South Wales or Victorian Health government websites, you can see them update the statistics daily, even less than a day so that the truth is it’s here and it’s probably in more people than we realise because we haven’t tested as many people and we now realise some people are asymptomatic or don’t show classic flu like symptoms. So it’s here and you can’t say that you’re not going to get sick. Alright? That’s the first thing to say. The second thing is, though, we can minimise what we do. Okay. So we can wash our hands constantly. We can try not to touch our face, our eyes, our ears, our nose. We’ve learned, for example, even how do you dispose of a tissue when you sneeze or cough or, you know, sneeze into your elbow? So it’s just about common sense. This is what I think. It’s no different really than protecting yourself from any respiratory virus infection. So seasonal flu or even a pandemic flu.

Sunanda Creagh: And how do you dispose of a tissue safely?

Lisa Sedger: Well, I guess you fold it in and then you put – you don’t touch it, you don’t put it up your sleeve, OK? – you put it in the garbage bin and wash your hands afterwards.

Sunanda Creagh: Michael would like to know: what can we learn from other countries that are handling this well? He says basically South Korea, as far as I can tell.

Michael Wallach: So the country that handled this outbreak the best so far has been Taiwan. The Taiwanese have been amazing in the sense that after the pandemic commenced in China, many Taiwanese returned to Taiwan. And you would have expected they’d seed that island very strongly and it would be a major outbreak. They were ready before the pandemic commenced. And that was largely because they went through a SARS outbreak. Previously, they had in place all the testing, all the people. They have the best health system in the world. And they kept the numbers down to 45 cases during a period when in China it was going into the tens of thousands. And they should be commended on that. It’s quite amazing the way they did that. The issue now in Taiwan, which concerns them, is in the end, that’s a great start. But their population now is unexposed and susceptible. So how do you release them from this sort of quarantine situation? That is the next phase. And that’s what we’re looking to see how that works, because same in Wuhan. The minute you put everyone back out to work and in the street, will there be a second wave? Most virologists, I think, would expect there will be a major second wave, third wave and maybe continued into the future. So we have to continue with our preparedness and with the hope that the vaccine will come into effect sooner rather than later. And then bringing the quarantine approach, enabling that peak of viral infection to occur when the vaccine is available. That would be the goal.

Lisa Sedger: If I could just add one point there. When you look at the number of cases on a per day basis in Wuhan, it was escalating very quickly. And then they brought in their very strict quarantine and self-isolation. But the cases continued to increase until a point where it started to look like it was under control and going down. And that was after two weeks. So quarantine only works until after the quarantine period, because only after that will you see the effect. So I would argue there’s two factors for why isolation worked in Wuhan: One was you limited the spread through the self-isolation and imposed quarantine, but at the same time, the number of people who are infected and asymptomatic were building their own immunity. The number of people who were infected and sick but who survived, one would imagine, have a robust immune response to that virus. So at the same time as limiting spread, you have also slowly built or actually quite quickly built a community with much higher levels of what we call herd immunity. So this second outbreak may come, but it may be considerably less significant.

Michael Wallach: In fact, that the areas where there are the major outbreaks maybe have better herd immunity than places where you keep it down to nothing. So it works both ways.

Sunanda Creagh: And Jane would like to know: when do we stop testing for this disease and basically just assume that everybody with the sniffles has it?

Michael Wallach: So first of all, the major symptoms are not sniffles, they are fever and coughing and shortness of breath. It’s the sniffles, though, that causes it to be spreadable more easily. That’s a good question: what the health authorities will decide to do at various stages of this pandemic. We’re now at what I would consider the early seeding phase. The world is now seeded with virus and different countries were going through exponential phases like described in Wuhan at different times. And how do they handle that will be a crucial question. I’ve seen all the different approaches from US, Israel, Iran. I think that a mixture of very strategic quarantine with travel restrictions, with bringing in other types of… certainly health authorities will need to control the number of beds that are being occupied. For example, again, in Israel, they just went over their bed limits, so patients are starting to be treated at home. So at some point, I think depending on how the epidemic goes, if we can keep it under control, we can keep the testing going. We can keep control. If the exponential rise is too fast, we will lose control and the testing will become meaningless. So the hope is that things will be sorted and I think Australia has the opportunity to do really well and big decisions have to be made now.

Lisa Sedger: There’s already a paper just this week published in The Lancet that profiles survivors versus those who have succumbed from the infection. And we’re starting to learn what some of those factors are. So as as clinicians can better predict who are likely to be the more seriously ill people, they can better predict who should go to hospital for treatment, and as Michael has said, who are better actually just treated at home.

Sunanda Creagh: And Dr. Sedger, Kardia would like to know: how does this virus respond to cold or warm temperatures? Is it like the flu, which thrives in cold weather?

Lisa Sedger: I have heard so many different things about this. I will be completely honest and say I’m not certain that we really know. What we know is when this high humidity viruses can exist for longer because they don’t dry out. So that envelope we talked about is less likely to be dried out. And once that’s dried out, the virus is less infective. It’s not actually infective at all if it’s disrupted that envelope. But whether it likes cold temperatures, high temperatures, we think it’s not a warm temperature virus. We think it’s more a cold temperature virus. China’s just been going through their winter. Maybe one of the reasons it’s been big in Italy is they’ve just had winter. We also think the coexistence of seasonal flu in Italy at the same time is probably one of the factors that’s made it more severe. So, yeah, look, different circumstances in different countries, different climates. It’s not just about climate, though. It’s about susceptibility of various populations. Therefore, it’s a hard question to answer (at the moment).

Michael Wallach: Look, I would say in working in infectious diseases for many years, it’s a very difficult thing to predict. Remember with, it doesn’t matter which disease I was working on, everyone said it can’t transmit in dry climates. And it transmitted beautifully in the desert. And you think everything’s totally dry and it still transmits and vice versa.

Lisa Sedger: Well, you’ve got MERS is another coronavirus, which is your Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome, and that’s in the desert climates. So that’s why I wanted to hedge my bets on my answer.

Sunanda Creagh: And Professor Wallach, this reader wants to know: once you’ve recovered from coronavirus, can you just go back to your normal, non-isolating life?

Michael Wallach: So the current understanding, according to colleagues also in the U.S., is if you go through one infection, you’re probably rendered immune against re-infection. There have been reports of cases of people getting re-infected. But the opinion that I heard so far is that it’s probably recurrence of the same infection that probably went down in terms of clinical symptoms. But the virus remained that just came back up. It happens with the flu all the time. The question is, what should be your behaviour after you go through a bout? I guess I would still be careful, which Lisa can maybe add to, it could be that the virus will continue to mutate. Although again, I fortunately heard this morning that they’re not that worried about this virus mutating at the rate that flu does. And we’re hopeful that we will develop herd immunity. People have gone through it then will be fairly safe unless, you have some immune disorder. And then it will become part of our environment just like flu is.

Sunanda Creagh: And here’s a question from me. It seems like there’s two camps. There’s the people who genuinely really concerned, quite worried about the situation. We see that in the panic buying. And then there’s the other camp of people who are saying it’s all been blown up. It’s all hype. We don’t really need to worry about it. It’s too early to panic. And I just wondered, how do you reconcile those two views out there in the community?

Michael Wallach: So early on in this outbreak, when I was interviewed also on the ABC and speaking to other groups, I took a very low panic view, maybe because I’ve been thinking about a pandemic for many years. And for me, it was always not a question of if, but when. I actually look at this, in a way, in a positive sense. We’re facing a pandemic that, yeah, as terrible as it is, is nothing in comparison to what could be if it’s a pandemic flu. For example, we experienced the Spanish flu in 1918, which killed somewhere between 20 to 50 million people. So the order of magnitude of mortality right now is extremely low compared to other potential pandemics. If you take China out of the equation, we’re at about 1500 people who died worldwide. That’s not to say we shouldn’t show great respect for the value of their lives. It’s mainly very elderly people with complicating illnesses and probably would have had the same effect if they were infected by flu. So my take on this whole thing is we all have to stay calm. We all have to accept the fact that this is part of nature. These viruses are out there all the time. We know them. I can detect now flu viruses in wildlife, birds that are coming into this country now, that can mutate and start affecting humans. So we have to be prepared. We have to face up to them, together in a collaborative way, in a scientific and professional way. And we could win. If we panic and react the way the market is, for example, of course, that’s that’s an improper way to react. Rather, this is part of being, of our biology. Viruses exist that can hurt us and they will always exist.

Lisa Sedger: Yeah. Look, I think there are a few factors that we can really learn from. So one is to work out where these viruses come from. And a lot of these RNA viruses exist in bats. They seem to be transmitted into wild animals through bat droppings. And I think one of the lessons we, the world all over, might need to learn is how we deal with the marketing and selling of wild animals that are then used for foods. That may then prevent these viruses from getting into the human population. So I think there are lessons to be learned, number one. But Michael, I would disagree with you in one sense “that it is maybe not as bad as pandemic flu”, on the other hand: we do have vaccines for flu, we do have anti-virals. And we have a whole world that has various levels of immunity to flu and different strains of flu. Whereas this virus is entering into a naive (non)-immune population. And that’s what’s so significant to start with. It may be that as our immunity at a population level increases, as a disease this will become far less significant. But the first outbreak of it in a naive, (non)-immune, (and a) “naive population” will always have the highest level of morbidity and mortality. And that’s where we have learned from other diseases like Ebola. As I mentioned, what we already know about flu, how we already control flu and the development of new and novel antiviral agents will be just as effective and important, I believe, as will the development of vaccines. So I think there’s a lot to learn to prevent this or limit, I should say, to limit these the severity of the outbreak and maybe even prevent it from happening again. As I say, if we stop trapping wild animals and eating them, we might prevent the outbreak of some of these type of RNA viruses.

Michael Wallach: So I certainly agree with that. And China is now putting into law a restriction on the sale of wildlife in their markets. What I’m trying to do, and I hope we both agree, is that in proportion to, for example, influenza, even seasonal flu that killed in one year I think up to 600,000 people worldwide, I’m just trying to put things into proportion. To prevent people from panicking. To understand that, yes, this is affecting the elderly. And anyone who is elderly, suffering from heart or respiratory conditions would certainly isolate themselves. So where my wife’s parents live, where they live in a retirement village, they made a decision to close off the entire village. Nobody’s allowed in, as a means of preventing – because they’re an elderly population – people bringing in COVID-19 and infecting that area. And I certainly agree with that sort of strategy.

Sunanda Creagh: And John would like to know: are the death rates likely to be lower in a country like Australia with lower rates of smoking than places such as China, Iran and Indonesia?

Lisa Sedger: Again, I think this is a little bit we have to watch and just wait and see. It’s very hard to predict these things. It was intriguing that some of the highest death rates in China appeared to be men as well as just the elderly. And that might be because there’s a high rate of long term smoking. So almost like an endemic lung pathology within that community that somehow exacerbated the disease. In Australia, we may find that there are different populations that are the most at risk. So we know, for example, the virus uses a receptor to get inside of cells that is a protein present on cardiac tissue. So people with known cardiac conditions may turn out to be at higher risk. And in a non-smoking type country, maybe people with existing heart conditions will turn out to be the most at risk. In America, we might find something quite different. What we might find is it’s more socio-economic. Maybe people without health insurance. Maybe people who are homeless and live on the streets will turn out to be the most affected because they have limited resources to be able to get treatment and they can’t afford treatment. So I think each country will be different. We mentioned earlier Italy has one of the highest fatality rates at the moment. That may be because they actually have a large number of people within their population that are over 65. So it might actually be not that surprising given that demographic. It might also be that they’ve had an outbreak of seasonal flu at the same time. We don’t know whether one type of virus limits the other. It’s quite possible you can get co-infections and that’s where people get the most sick. I think it’s going to pan out in different countries slightly differently. I think it’s a case of watch this space.

Michael Wallach: The other thing, just on the rate of transmission. What they go according to is the people who show up to the clinic. And the results from a study done in China indicate that they may have only picked up 5% of the people that have COVID-19. So it’s about 20-fold more than actually recorded because it’s mild and very little symptoms. The other thing that’s becoming a little disconcerting for scientists is there may be two strains of the virus. And the initial outbreak, as I said, the mortality rate was very high. It could be the virus, in order to transmit, went through a mutation that aided its transmission. And I would hope that would probably occur in pandemic flu. Maybe a little less pathogenic than the original strain was. I was surprised to see at the beginning such high mortality and then how it dropped down. That’s the results also put online by the CDC. And we’re looking and following that.

Lisa Sedger: Yes, viral evolution is a really key topic at the moment. We think RNA viruses and the rate that they mutate is much higher than DNA viruses. And it’s really a factor of how quickly the virus mutates and how quickly a person’s immune response is able to effectively control the virus replication. So the viruses that sometimes persist longer in a community are not necessarily the most virulent. So what we might also be seeing is a population, a group within the population who get a less severe disease, maybe even asymptomatic, but that may, long term, prove to be the bigger – how could I put this? – the bigger population of viruses that exist within that community.

Sunanda Creagh: And Michael would like to know: if I could shrink myself down to microscopic size and watch a virus invade a cell, what would I see?

Lisa Sedger: Well, a virus is not like a bacteria. A bacteria is a entity all of its own, and it can replicate and make another copy of itself and grow on a nutrient source. A virus, however, is sometimes called a non-living entity because outside of a human cell, it can’t replicate. It just exists as an entity. A virus is essentially just a piece of DNA, which is, you know, in the nucleus of every cell. It’s what our chromosomes are made of. So it’s either DNA or RNA surrounded by a protein coat and sometimes it’s also a lipid-based envelope outside of that, again. The virus will somehow encounter a cell. And for respiratory viruses, it’s largely by us inhaling water vapour droplets. They may contain hundreds of viruses. Those viruses then will attach or be exposed to our respiratory epithelium. If the virus can actually bind to the respiratory epithelium cell, then it might get inside. Once inside, it may or may not have the capacity to actually undergo replication, but it has to uncoat from that protein shell. Then the nucleic acid, the DNA or RNA has to make another copy of itself. Then all the genes that are in the virus have to get expressed as proteins. They then reassemble into a new viral particle and then the virus will get out of the cell. Sometimes it lyses (breaks) the cell, sometimes it will just buds out from the cell and leave the cell intact. And that’s what a virus is. That’s why we, some people call them living or non-living because they can only replicate in inside a cell, a host cell.

Michael Wallach: And it’s not like viruses have a will. So if they want to do this, it’s just part of evolution.

Lisa Sedger: Yes, I’m never a favour of the argument you sometimes see people say “it’s warfare, it’s the virus vs. immune system!” But there’s no will involved, it’s just capacity of life to replicate itself.

Sunanda Creagh: And Deidre writes in to say, I heard on the radio today that half the population is likely to get this. And with, say, a 1% death rate, the body count will add up. And I wondered what you thought of that.

Michael Wallach: So there was an announcement actually by Angela Merkel preparing Germany for 70% of the population being infected. Lisa may say the number is lower, I don’t know, until we build up herd immunity. The question of the mortality rate, as I alluded to before, I think based on what again, CDC and WHO are writing, is probably overestimated. Some estimate the mortality rate as being much lower. That’s not to say… every death is a family and has to be looked at and be concerned about. So again, I think and would like to hope that as we develop new vaccines, as we develop drugs, as we develop approaches to quarantine people, test them, keep them at home, isolate them, we’ll get the mortality rate under control. And I’m going to express an optimistic view. This world has amazing capabilities of doing amazing science. And if we apply it and work together, I think we can control this problem.

Lisa Sedger: Yes, absolutely. I would endorse that. And I’d say that the mortality rates at the moment simply reflect who is being tested. And it’s primarily people who are turning up with symptoms. But we’re now beginning to appreciate that there is a large number of people who could be quite asymptomatic, who are never tested. This virus will certainly have infected many more people than will be tested. And if we did have surveillance of every single person being tested, then there’s two questions here: Are you testing for the presence of the virus? If they’ve had virtually no symptoms and not a big illness, you might not find the virus. But if we test for the presence of an immune response to the virus, we would truly know how many people have been infected. And then we could get a true estimate or at least a much closer estimate of what the mortality rate really is. So at the moment, there’s hyperbole.

Sunanda Creagh: And Catherine asks, what is the likelihood of transmission through using a public swimming pool?

Lisa Sedger: I would think quite small because a) the virus would be quite diluted in a swimming pool. Secondly, swimming pools are all treated with chlorine, for example, and chlorine is a very effective anti-viral agent. You’d have to drink a lot of swimming pool water to get the virus.

Michael Wallach: I agree with that.

Sunanda Creagh: Candy would like to know: there are conflicting symptoms lists circulating on Facebook. One says it starts with a dry cough and if your nose is running, it is not COVID-19, which I suspect is incorrect. Can we please have an accurate list?

Michael Wallach: So, again, the major symptoms are, in fact, the cough and shortness of breath and fever. But, it’s not to say it’s not possible that you’ll have also upper respiratory effects. The virus goes into the lung and attaches to the alveolar cells or to the cells that make up our air sacs and that help our breathing. And it has to get there to really cause this disease. So if there’s upper respiratory involvement, which includes sneezing and runny nose, et cetera, it’s probably not the main effect of the virus. Again, I would say if you see that somebody is sneezing and wheezing and and that’s it, it’s probably an allergy, but it does frighten people. I was on the train this morning, and I know if I, God forbid, sneezed the whole train would empty out pretty quickly.

Lisa Sedger: You know, we’re just coming into winter. And actually, it’s a really good question because at the moment, what’s building is a sense of fear. But we must keep in perspective that there will also still be the normal seasonal cases of flu. So just because somebody sneezes or has a sore throat does not mean that they’ve got COVID-19. And we need to make sure, I think it’s really important that we don’t stigmatise people who have symptoms because it may not even be COVID. And we’re all at risk from any respiratory tract infections and already have been for years. That’s not a new thing. We just need to keep things in perspective.

Sunanda Creagh: A question from Karen: can you catch it twice?

Lisa Sedger: Normally, I would have said no, because we imagine that there’s a good immune response that will then provide you protection from re-infection. That’s what our immune system does. But this is a new virus. We don’t yet fully understand how our immune system clears it. We don’t know whether virus can remain for a longer period of time. I would would say, though, that there are only a few cases of people who have been treated, appear to have recovered, they’ve gone home, they’ve then had another relapse. There’s only a very few number of cases that have been like that. So for all intents and purposes, I don’t think that’s something we should fear and it’s not something we’ve seen with the previous SARS outbreak in 2003.

Sunanda Creagh: And Tim would like to know: how will quarantine work in a family?

Lisa Sedger: Yeah, it’s interesting, isn’t it? We think of quarantine as being away from work or away from public places. But really, if you have been infected, then the people in your family are as at risk as your work colleagues would be at work. Again, I think it’s about just common sense. Don’t share food utensils, wash your hands, don’t keep touching your face and your mouth and your nose. Get rid of tissues in a nice sort of clean manner. It’s about minimising transmission.

Michael Wallach: Let me just add to that, that all the data indicates that children likely will only get very mild symptoms, if at all. So if you’re a family member and you’re worried about your children, this is one time that you can be happy about this. All the results so far indicate that children aged zero to nine, there’s not been a single death.

Lisa Sedger: Whereas what we do know is the elderly appear to be more susceptible to a more severe disease. So that’s where if I’m sick, it’s better not to go and visit my grandparents or something like that. That’s where quarantine within the family works in a practical sense.

Sunanda Creagh: And just to finish up, is there anything else that you’d like to add?

Lisa Sedger: Yeah, I think I’d just want to finish with a really positive note. I mean, we live in an amazing era of medical research and science. Within within a very, very short period of time, parts of the virus had been sequenced. We now track the virus in its entire sequence. We know, we have clinical trials for the drugs. We have people working on vaccines. We have epidemiologists better understanding the disease susceptibility within a population. I mean, we learn a lot from other existing outbreaks of infectious diseases. And I remain positive that, you know, the medical and scientific community working together will be able to solve this. I’m quite confident that there’s a really strong response. That’s not to diminish that people have died and it’s been tragic. But we live in an era where we’re exposed to infectious agents and we are getting better and better at controlling most of those infections.

Michael Wallach: So I’ll just add and put in a plug for a program I’m very much involved with called Spark working with people at Stanford. We established a program for exactly this time, when there’s sudden outbreaks. And the program now involves 23 countries and around 70 institutions, all working together for outbreaks of Zika, Ebola and now coronavirus. It gives me great hope that, apart from what you said, we’re now working together collaboratively like never before. We’re putting our egos outside and we’re saying we have social responsibility to do better. Certainly, in the case of a pandemic. And we’re doing it. And we’re very proud to be able to say we have 15 projects going on now collaboratively that we just formed over the past two weeks, together with our colleagues all over the world. I also believe in a very bright future.

Production credits

Recording by postgraduate.futures at the University of Technology Sydney.

Audio editing by Sunanda Creagh.

Theme beats by Unkle Ho from Elefant Traks.

Read more: Coronavirus is stressful. Here are some ways to cope with the anxiety

– ref. Coronavirus and COVID-19: your questions answered by virus experts – https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-and-covid-19-your-questions-answered-by-virus-experts-133617