Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Hassan Vally, Associate Professor, La Trobe University

To understand the spread of COVID-19, the pandemic is more usefully viewed as a series of distinct local epidemics. The way the virus has spread in different countries, and even in particular states or regions within them, has been quite varied.

A New Zealand study has mapped the coronavirus epidemic curve for 25 countries and modelled how the spread of the virus has changed in response to the various lockdown measures.

The research, which is yet to be peer-reviewed, classifies each country’s public health response using New Zealand’s four-level alert system. Levels 1 and 2 represent relatively relaxed controls, whereas levels 3 and 4 are stricter.

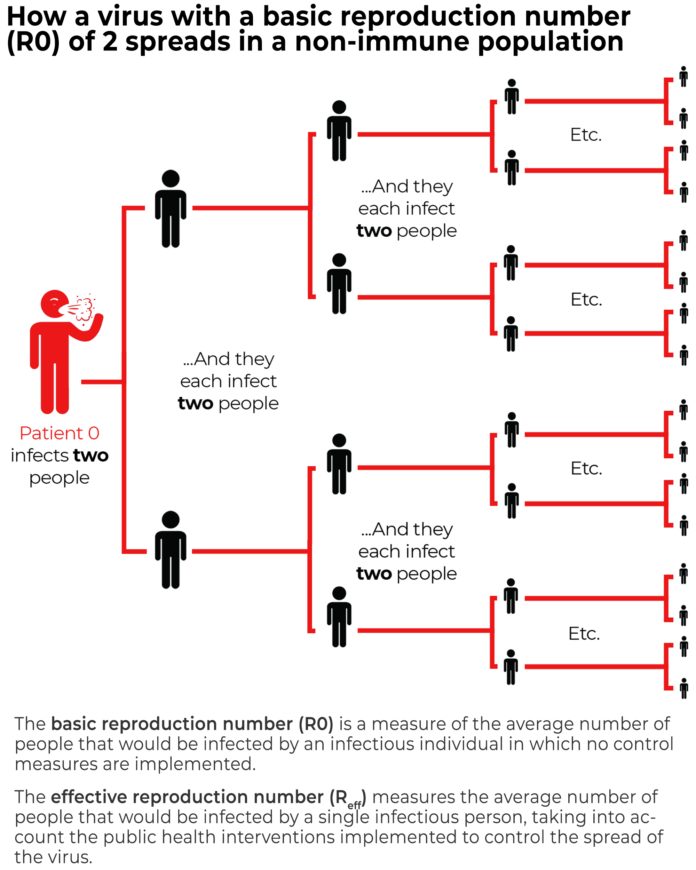

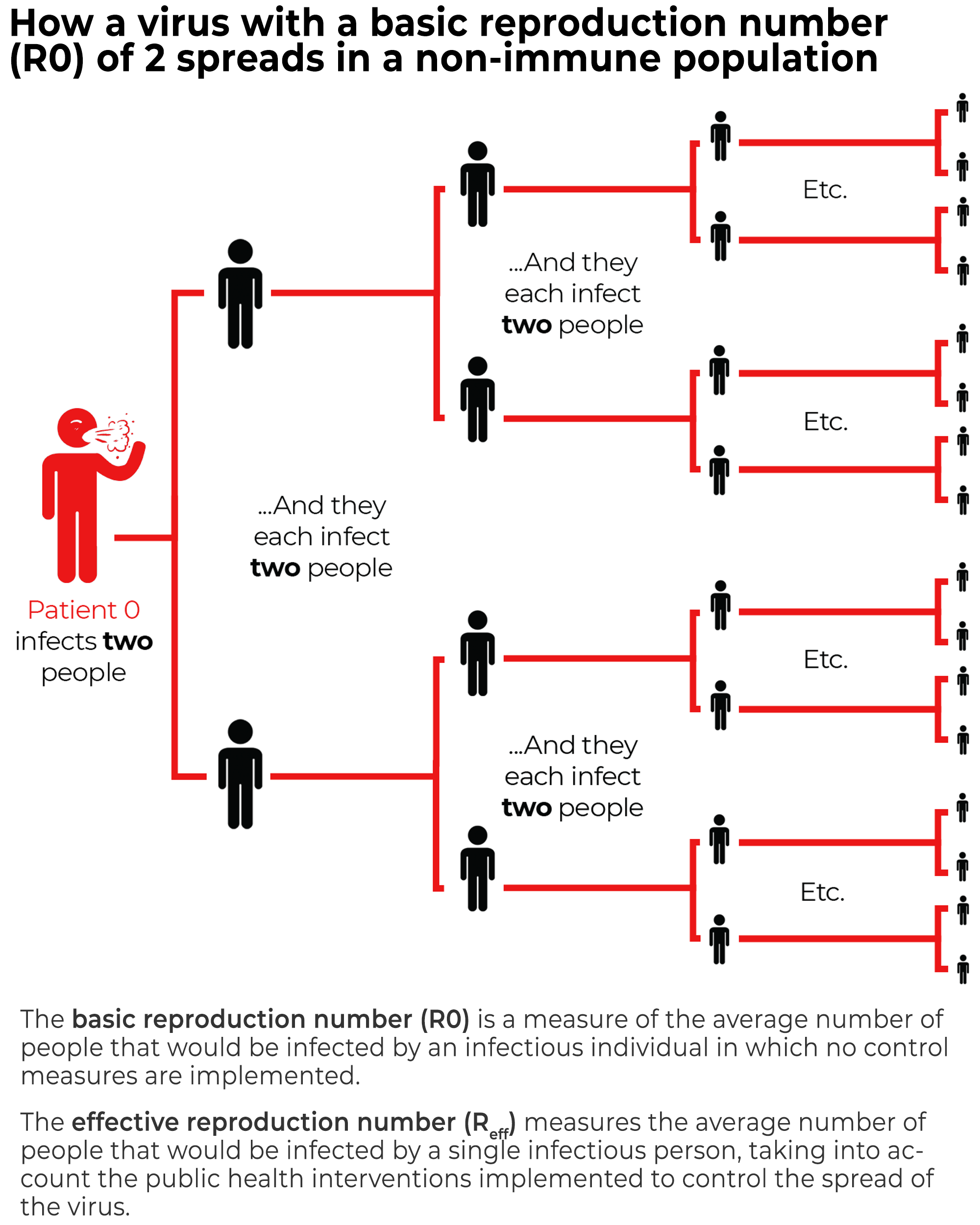

By mapping the change in the effective reproduction number (Reff, an indicator of the actual spread of the virus in the community) against response measures, the research shows countries that implemented level 3 and 4 restrictions sooner had greater success in pushing Reff to below 1.

An Reff of less than 1 means each infected person spreads the virus to less than one other person, on average. By keeping Reff below 1, the number of new infections will fall and the virus will ultimately disappear from the community.

Conversely, the larger the Reff value, the more freely the virus is spreading in the community and thus the faster the number of new cases will rise. This means a higher number of cases at the peak of the epidemic, a greater risk of the health system becoming overwhelmed, and ultimately more deaths.

Here are some of study’s findings from states and nations around the world:

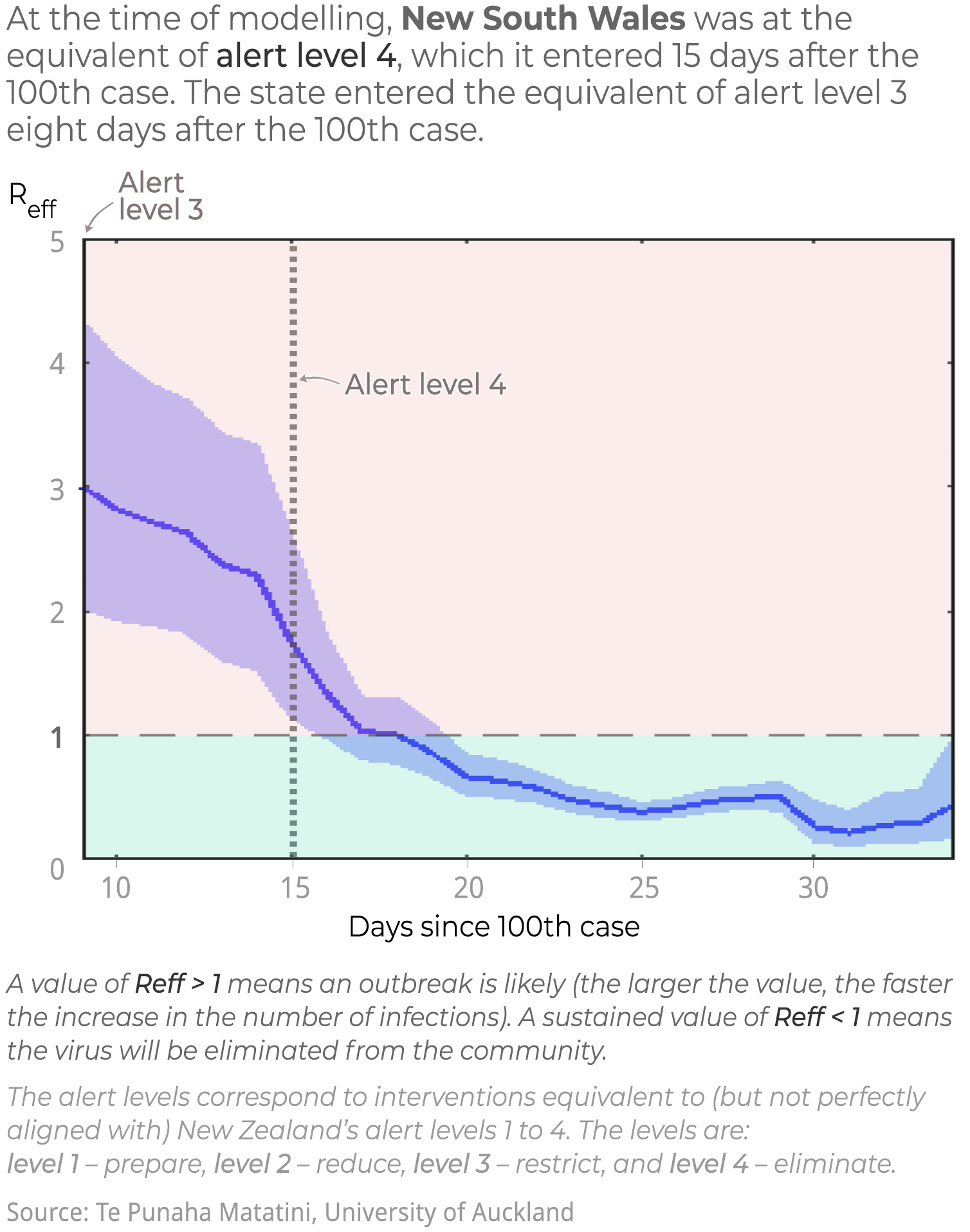

New South Wales, Australia

The effect of Australia’s strict border control measures, implemented relatively early in the pandemic, can clearly be seen in the graph below. Federal and state governments introduced strict social distancing rules; schools, pubs, churches, community centres, entertainment venues and even some beaches were closed.

This prompted the Reff value to drop below 1, where it has stayed for some time. Australia is rightly regarded as a success story in controlling the spread of COVID-19, and all states and territories are now mapping their paths towards relaxing restrictions in the coming weeks.

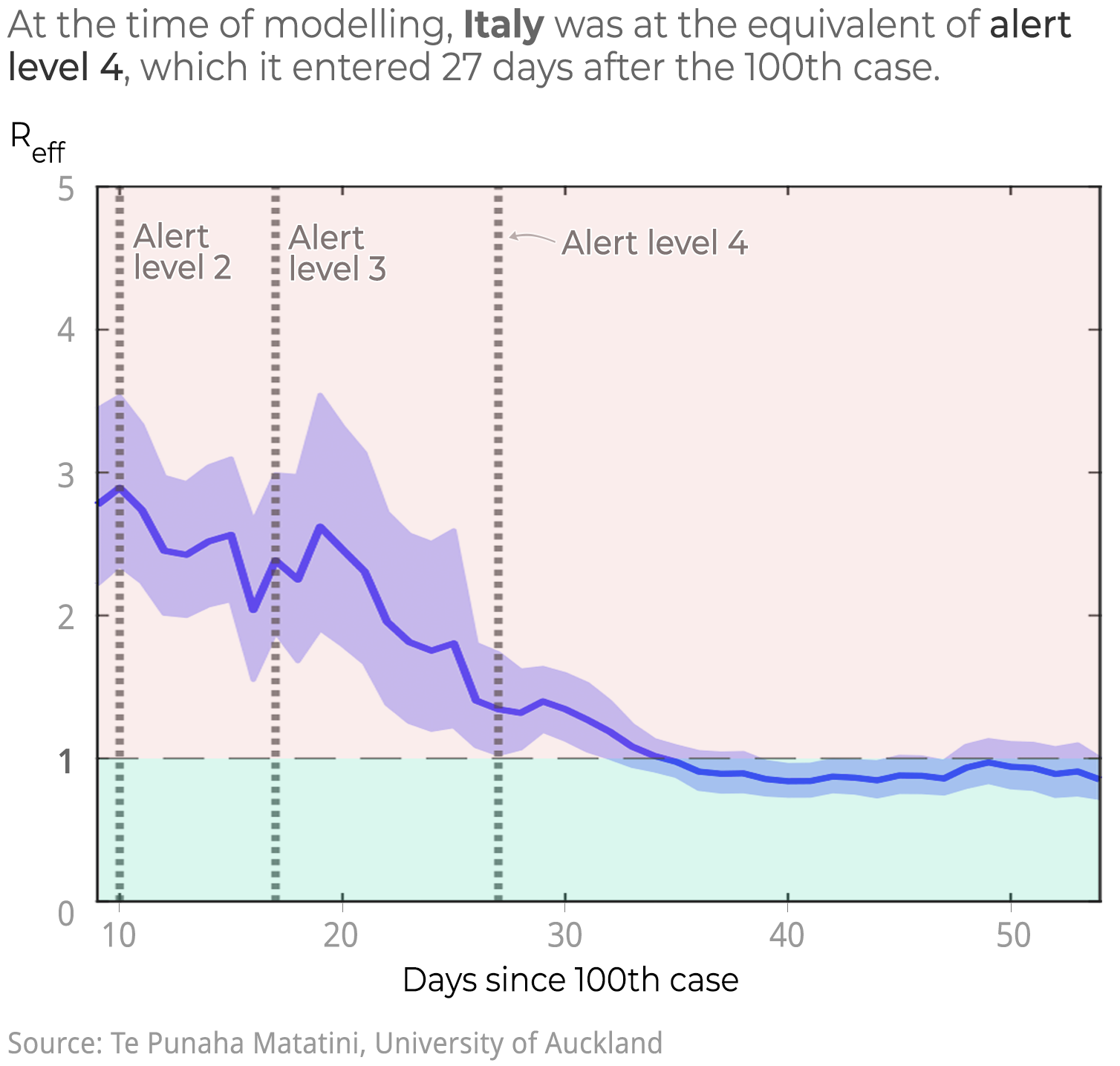

Italy

Italy was relatively slow to respond to the epidemic, and experienced a high Reff for many weeks. This led to an explosion of cases which overwhelmed the health system, particularly in the country’s north. This was followed by some of the strictest public health control measures in Europe, which has finally seen the Reff fall to below 1.

Unfortunately, the time lag has cost many lives. Italy’s death toll of over 27,000 serves as a warning of what can happen if the virus is allowed to spread unchecked, even if strict measures are brought in later.

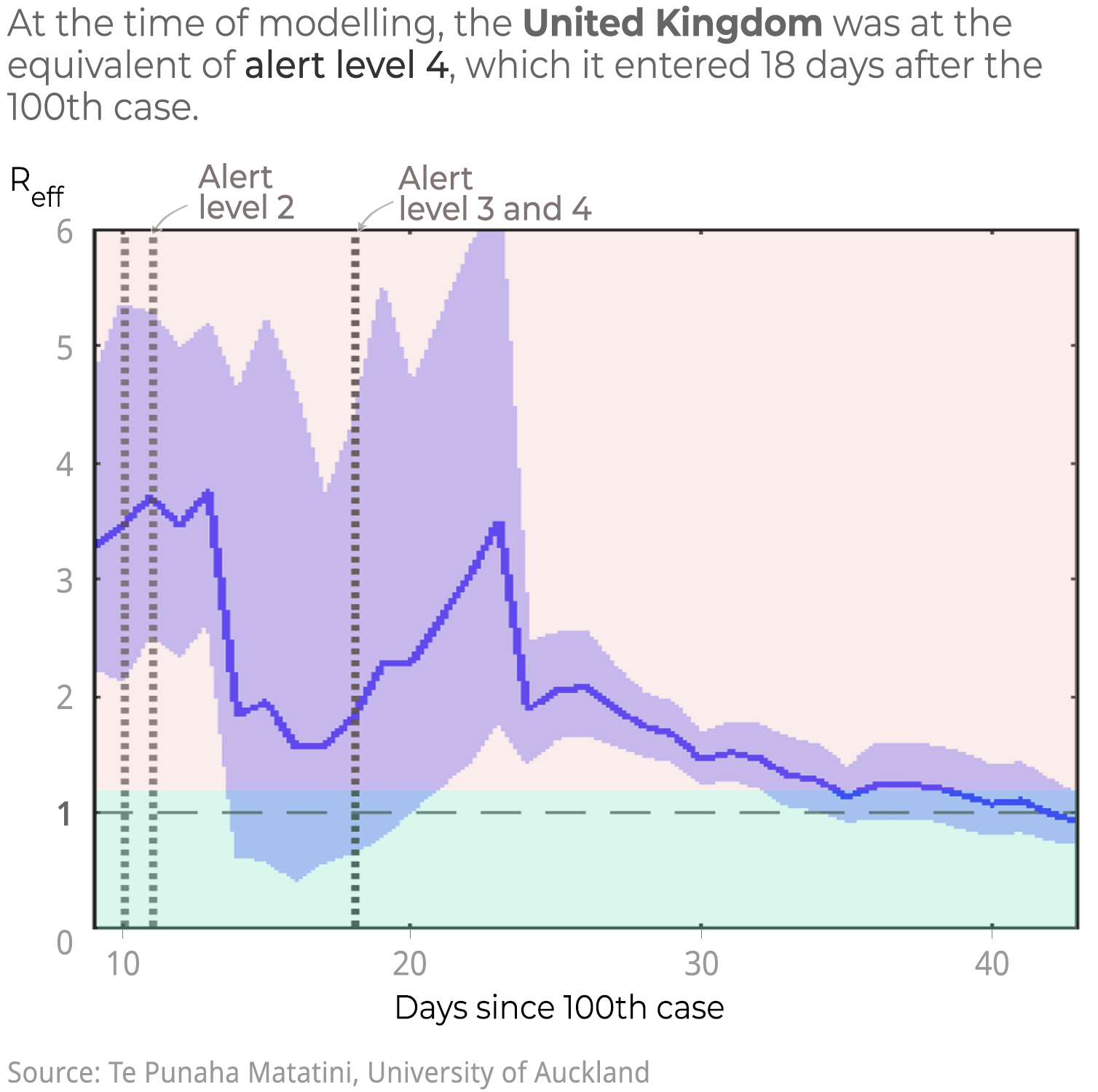

United Kingdom

The UK’s initial response to COVID-19 was characterised by a series of missteps. The government prevaricated while it considered pursuing a controversial “herd immunity” strategy, before finally ordering an Italy-style lockdown to regain control over the virus’s transmission.

As in Italy, the result was an initial surge in case numbers, a belatedly successful effort to bring Reff below 1, and a huge death toll of over 20,000 to date.

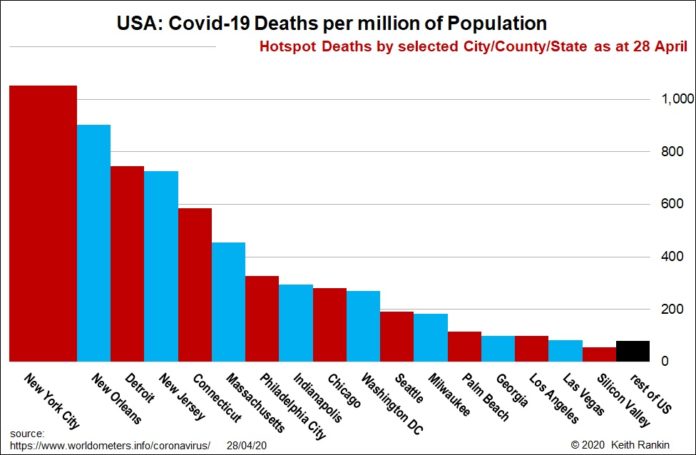

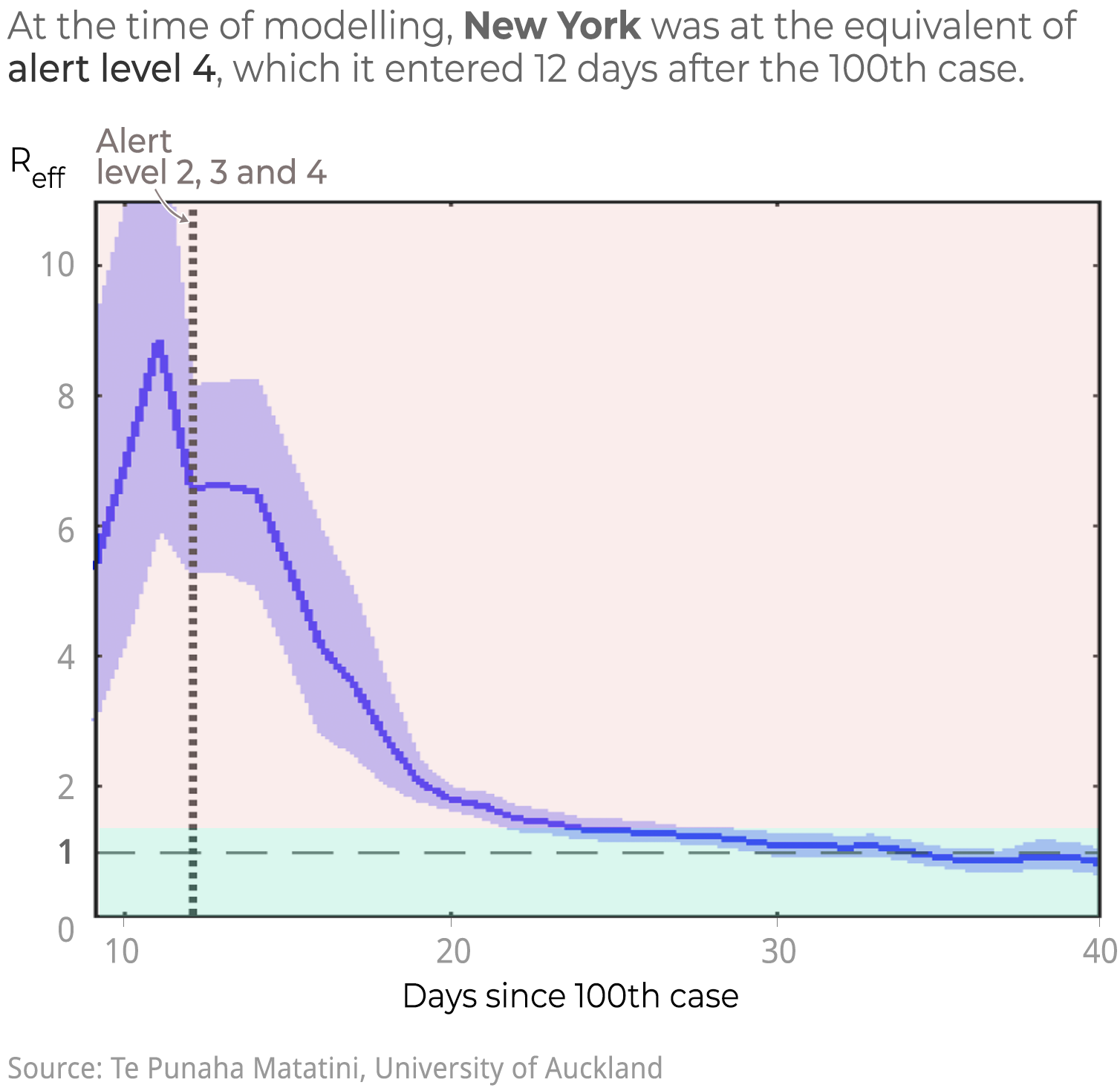

New York, USA

New York City, with its field hospital in Central Park resembling a scene from a disaster movie, is another testament to the power of uncontrolled virus spread to overwhelm the health system.

Its Reff peaked at a staggeringly high value of 8, before the city slammed on the brakes and went into complete lockdown. It took a protracted battle to finally bring the Reff below 1. Perhaps more than any other city, New York will feel the economic shock of this epidemic for many years to come.

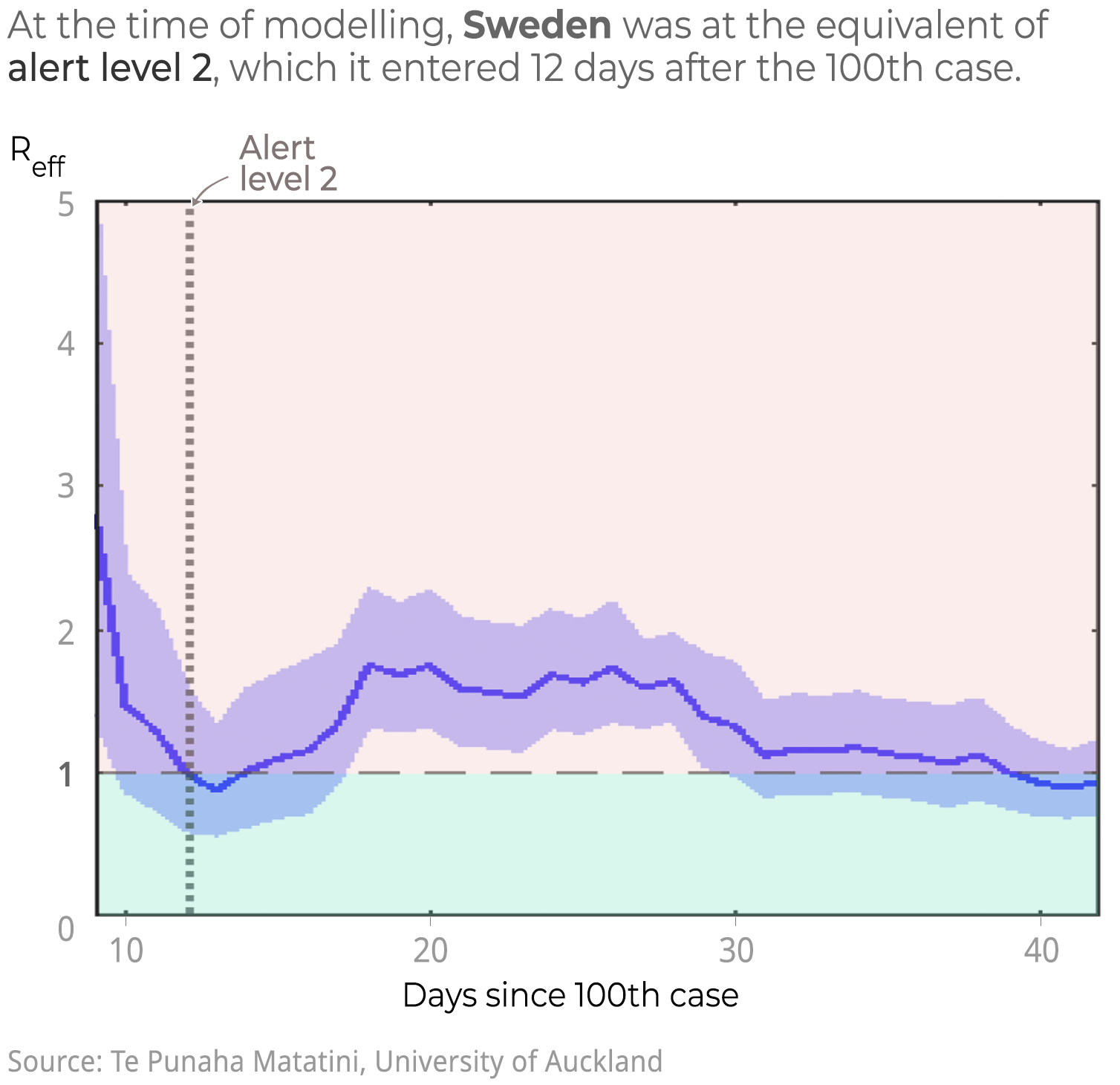

Sweden

Sweden has taken a markedly relaxed approach to its public health response. Barring a few minor restrictions, the country remains more or less open as usual, and the focus has been on individuals to take personal responsibility for controlling the virus through social distancing.

This is understandably contentious, and the number of cases and deaths in Sweden are far higher than its neighbouring countries. But Reff indicates that the curve is flattening.

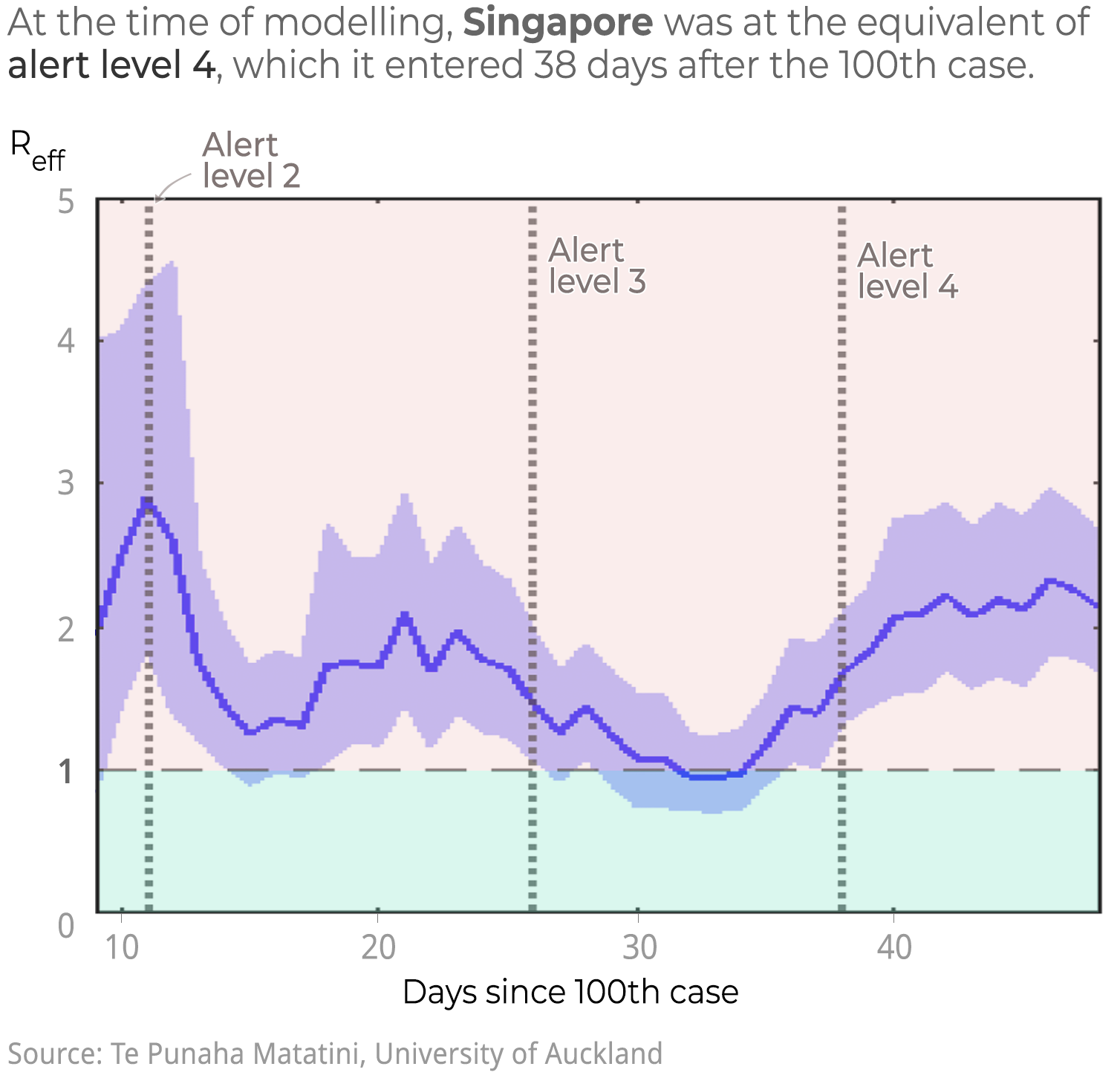

Singapore

Singapore is a lesson on why you can’t ever relax when it comes to coronavirus. It was hailed as an early success story in bringing the virus to heel, through extensive testing, effective contact tracing and strict quarantining, with no need for a full lockdown.

But the virus has bounced back. Infection clusters originating among migrant workers has prompted tighter restrictions. The Reff currently sits at around 2, and Singapore still has a lot of work to do to bring it down.

Individually, these graphs each tell their own story. Together, they have one clear message: places that moved quickly to implement strict interventions brought the coronavirus under control much more effectively, with less death and disease.

And our final example, Singapore, adds an important coda: the situation can change rapidly, and there is no room for complacency.

– ref. 6 countries, 6 curves: how nations that moved fast against COVID-19 avoided disaster – https://theconversation.com/6-countries-6-curves-how-nations-that-moved-fast-against-covid-19-avoided-disaster-137333