Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Brian Oliver, Research Leader in Respiratory cellular and molecular biology at the Woolcock Institute of Medical Research and Professor, Faculty of Science, University of Technology Sydney

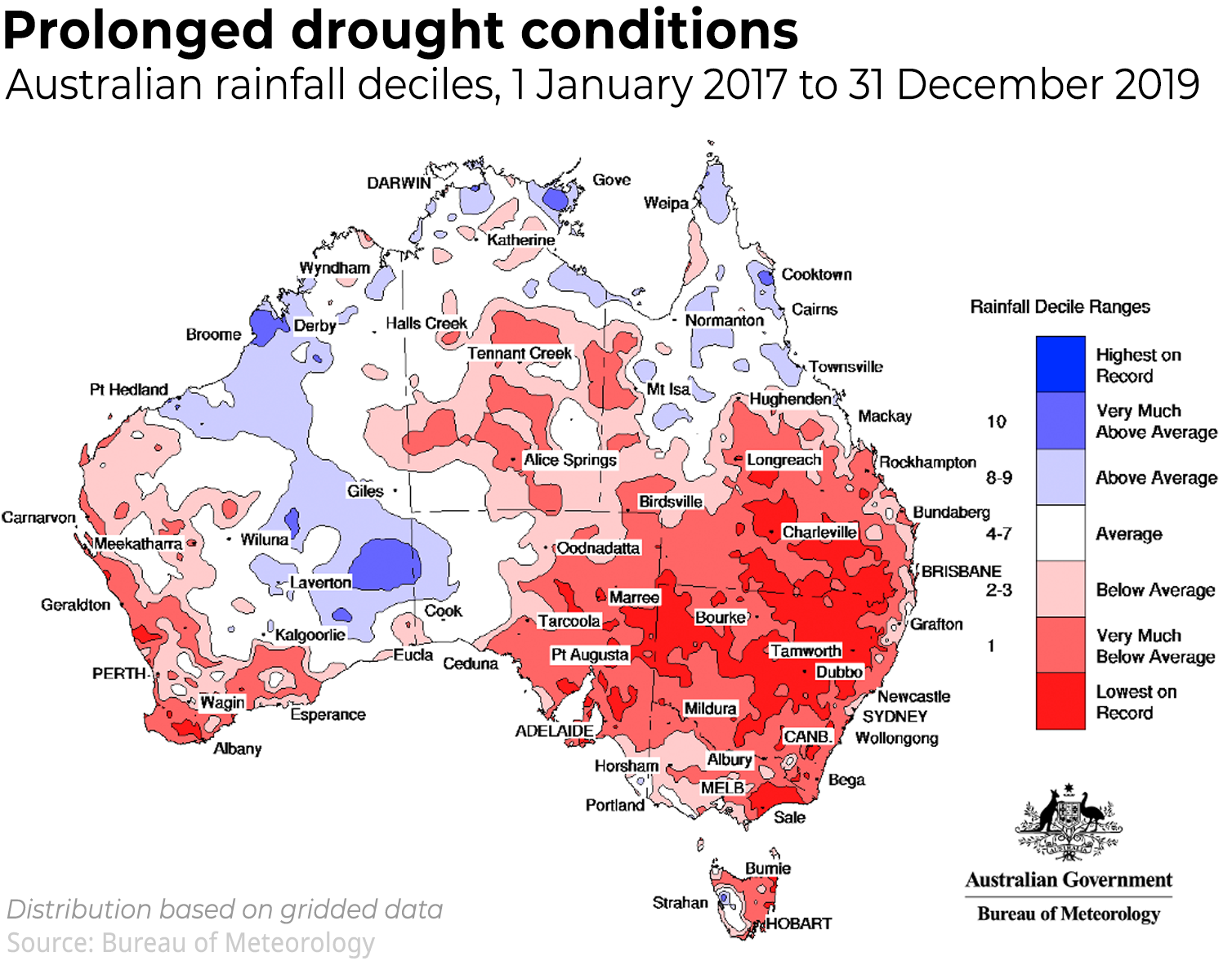

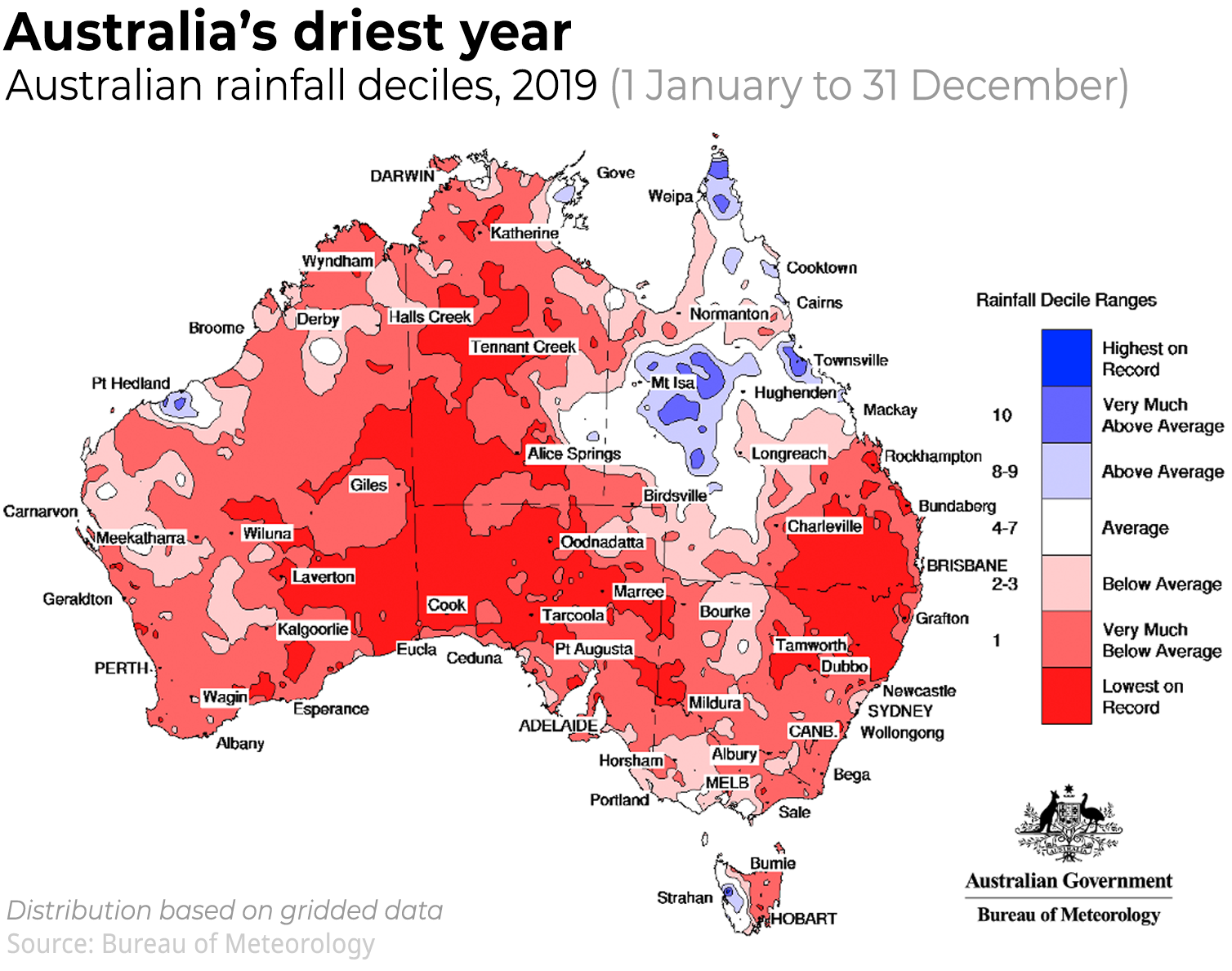

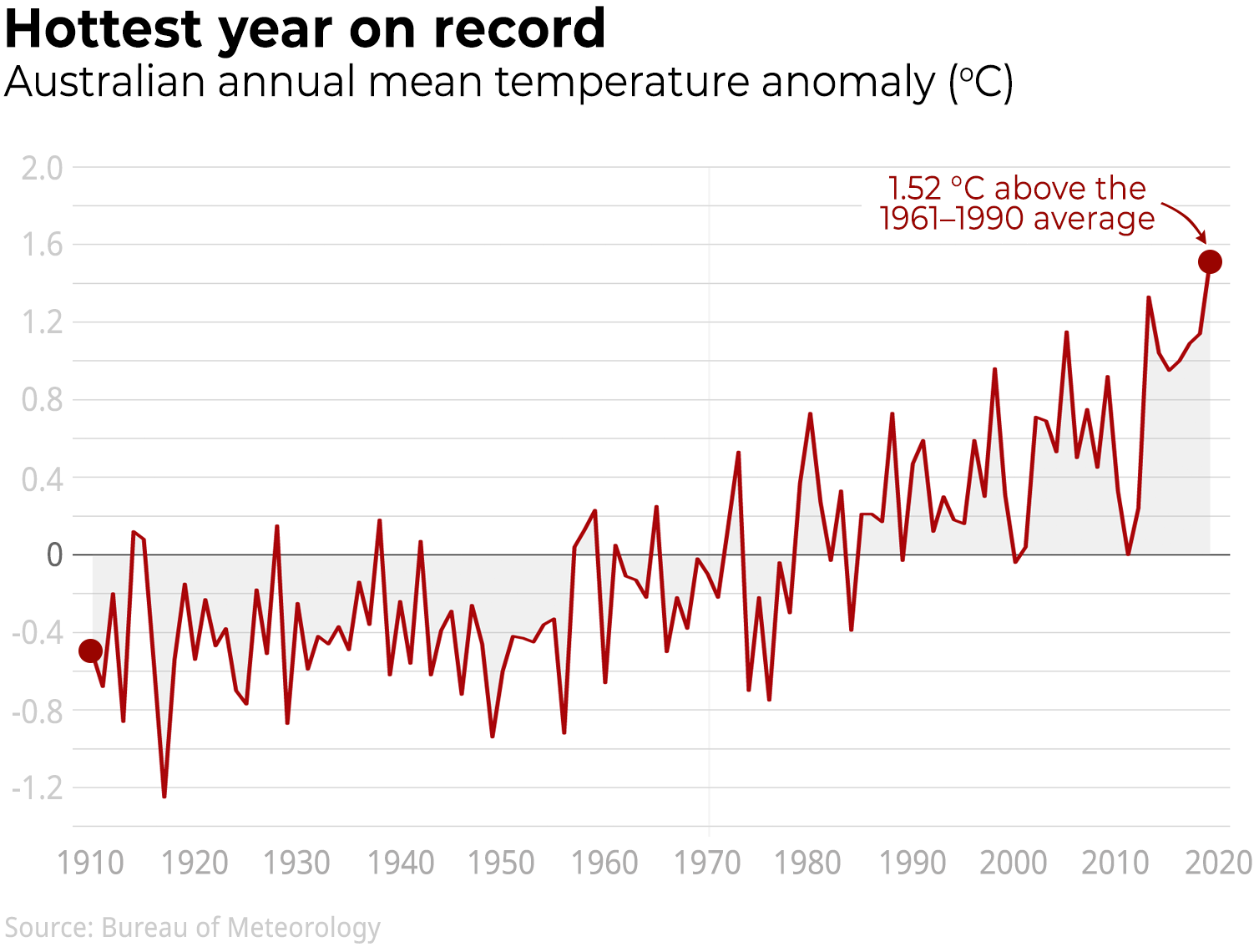

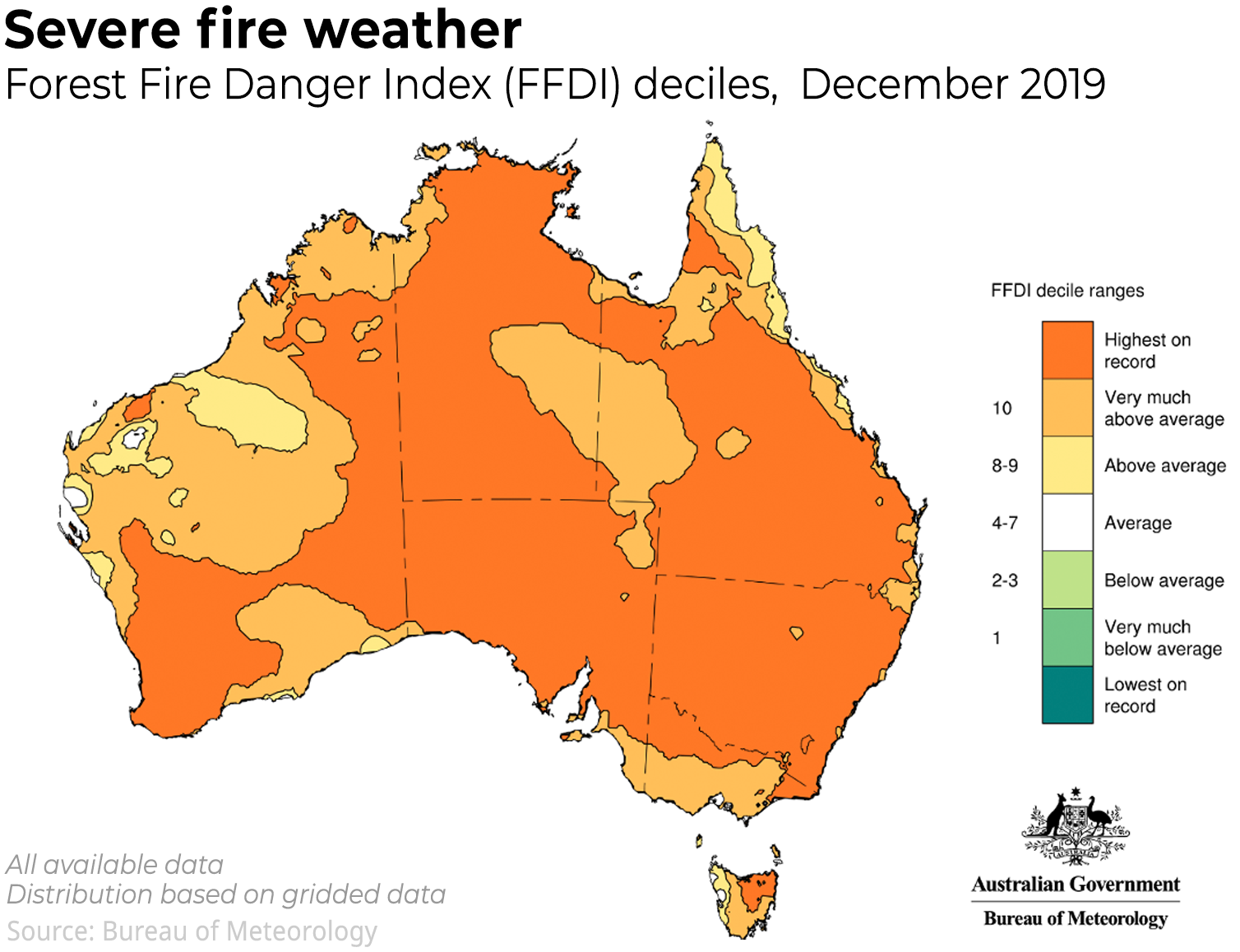

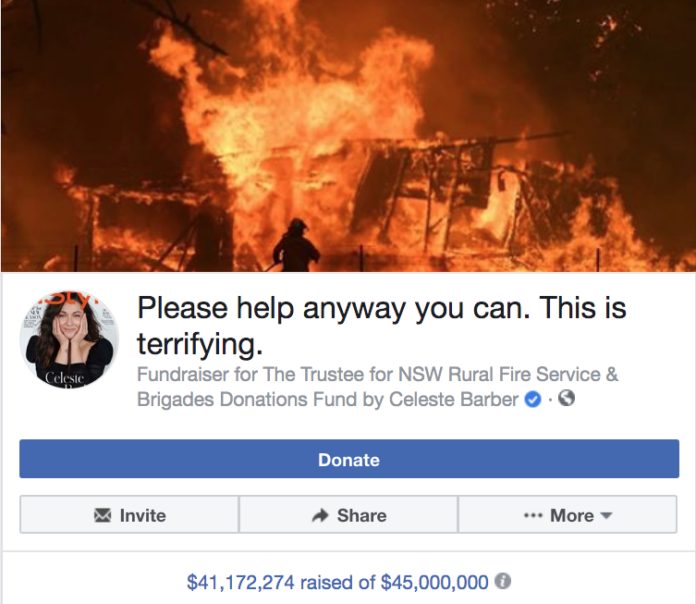

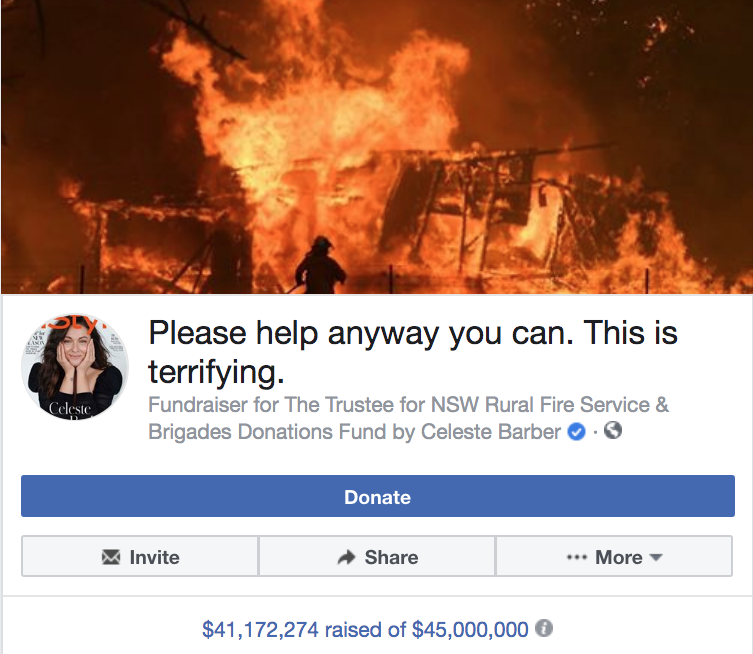

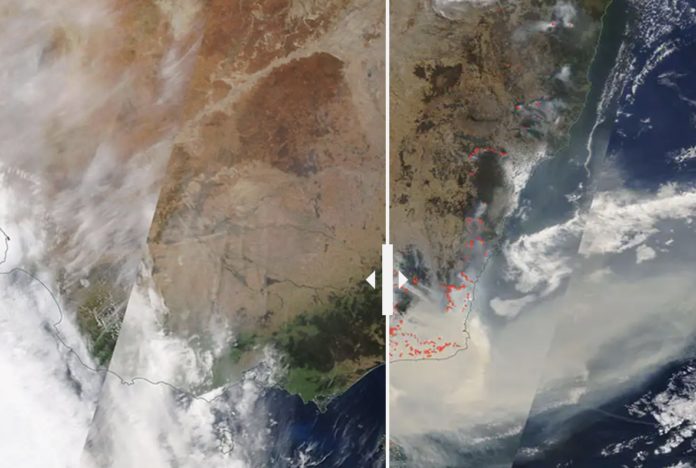

In previous years, Australians might have been exposed to bushfire smoke for a few days, or even a week. But this bushfire season is extreme in every respect. Smoke haze has now regularly featured in Australian weather reports for several weeks, stretching across months in some areas.

What we considered to be short-term exposure we must now call medium-term exposure.

Given this is a new phenomenon, we don’t know for sure what prolonged exposure to bushfire smoke could mean for future health. But here’s what air pollution and health data can tell us about the sorts of harms we might be looking at.

Read more: Climate change set to increase air pollution deaths by hundreds of thousands by 2100

Short-term effects

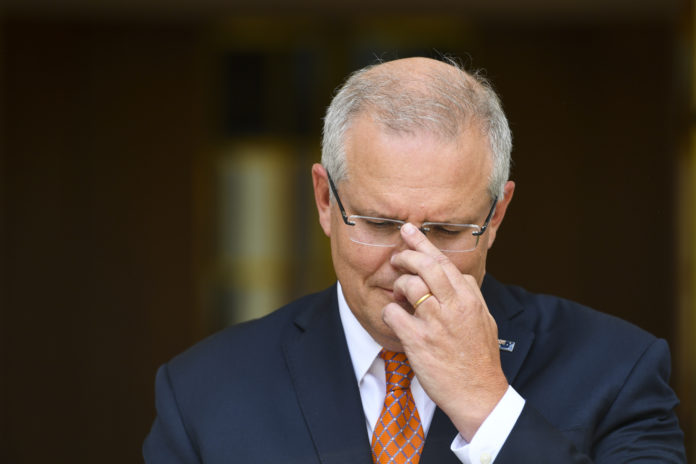

We know poor air quality is having immediate effects, from irritated eyes and throats, to more serious incidents requiring hospital admission – particularly for people with existing respiratory and heart conditions.

After the smoke haze hit Melbourne on Monday, Ambulance Victoria recorded a 51% increase in calls for breathing difficulties.

This aligns with Australian and international research on the acute effects of exposure to bushfire smoke.

But the long-term effects aren’t so clear.

Long-term effects: what we know

When considering the long-term health consequences of air pollution, we draw on data from heavily polluted regions, typically in Africa, or Asia, where people are exposed to high levels of airborne pollution for years.

It’s no surprise long-term exposure to air pollution negatively affects health over their lifetime. It’s associated with an increased risk of several cancers, and chronic health conditions like respiratory and heart disease.

The World Health Organisation estimates ambient air pollution contributes to 4.2 million premature deaths globally per year.

A recent study in China reported long-term exposure to a high concentration of ultrafine particles called PM2.5 (which we find in bushfire smoke) is linked to an increased risk of stroke.

Read more: How does poor air quality from bushfire smoke affect our health?

We also know the dose of exposure is important. So the worse the pollution, the greater the the health effects.

It’s likely some of these long-term effects will occur in Australia if prolonged bushfires become an annual event.

Experimental studies

Observational studies, like the Chinese one mentioned above, demonstrate the long-term health effects of long-term exposure to air pollution. But we don’t really have any studies like this following populations which have experienced short- or medium-term exposure.

To explore the health risks of more limited exposure, we can look to experimental data from cell and animal models.

These studies follow the models for days (short-term) or weeks (medium-term). They show exposure to any type of airborne pollution – from traffic, bushfires, wood or coal smoke – is detrimental for health.

The results show increased inflammation in the body, and depending on the model, increased incidence of respiratory or heart disease.

What about bushfire smoke?

We don’t have a lot of experimental data on the effects of bushfire smoke specifically, apart from a few studies on cells in the lab.

In my lab we’ve found the short-term in-vitro effects of bushfire smoke are comparable to the smoke from cigarettes. This does not however mean the long-term heath effects would be the same.

Read more: Pregnant women should take extra care to minimise their exposure to bushfire smoke

If we think about what’s burning during a bushfire – grass, leaves, twigs, bushes and trees – it’s also reasonable to draw on experimental data from wood smoke.

Wood smoke contains at least 200 different chemicals; some of them possible carcinogens.

In one small study, ten volunteers were exposed to wood smoke for four 15 minute periods over two hours. Afterwards, participants experienced increased neutophis, a type of agressive white blood cell, in both their lungs and circulation. The concentration of particulate matter in the wood smoke was lower than the levels we’ve seen in Sydney.

These short term studies show bushfire smoke is toxic, and it’s this toxicity which is likely to cause long-term effects.

One review found lifelong exposure to wood smoke, for example from indoor heaters, is associated with a 20% increased risk of developing lung cancer. Though it’s important to remember this is long-term exposure; the risks associated with medium-term exposure are not yet known.

How can we apply these findings?

Taking data from one type of airborne pollution and applying it to different pollutants – for example comparing the smoke from only one type of wood to bushfire pollution – is complex. The chemical make up is likely to differ between pollutants, so we need to be cautious extrapolating results.

We also need to be wary about how we translate results from cell and animal studies to humans. Different people are likely to respond to bushfire smoke differently. Our genetic make up is important here.

And with variable factors like at what age the exposure starts, how long it lasts, and other factors we’re exposed to during our lives (which don’t exist in a petri dish), it’s difficult to ascertain how many people will be at risk, and who in particular.

Looking past the haze

The human body actually has a remarkable capacity to cope with air pollution. It appears our genes help protect us from some of the toxic effects of smoke inhalation.

But this doesn’t mean we’re immune to the effect of bushfire smoke; just that we can tolerate a certain amount.

So would a once in a lifetime medium-term exposure have a chronic effect? At the moment there’s no way of answering this.

Read more: How rising temperatures affect our health

But if, as many people fear, this medium term exposure becomes a regular event, it could cross into the long-term exposure we see in some countries, where people are exposed to poor air quality for most of the year. In this scenario, there’s clear evidence we’ll be at higher risk of disease and premature death.

For now, we desperately need studies to help us understand the effects of medium-term exposure to bushfire smoke.

– ref. We know bushfire smoke affects our health, but the long-term consequences are hazy – http://theconversation.com/we-know-bushfire-smoke-affects-our-health-but-the-long-term-consequences-are-hazy-129451