Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Michelle H Lim, Senior Lecturer and Clinical Psychologist, Swinburne University of Technology

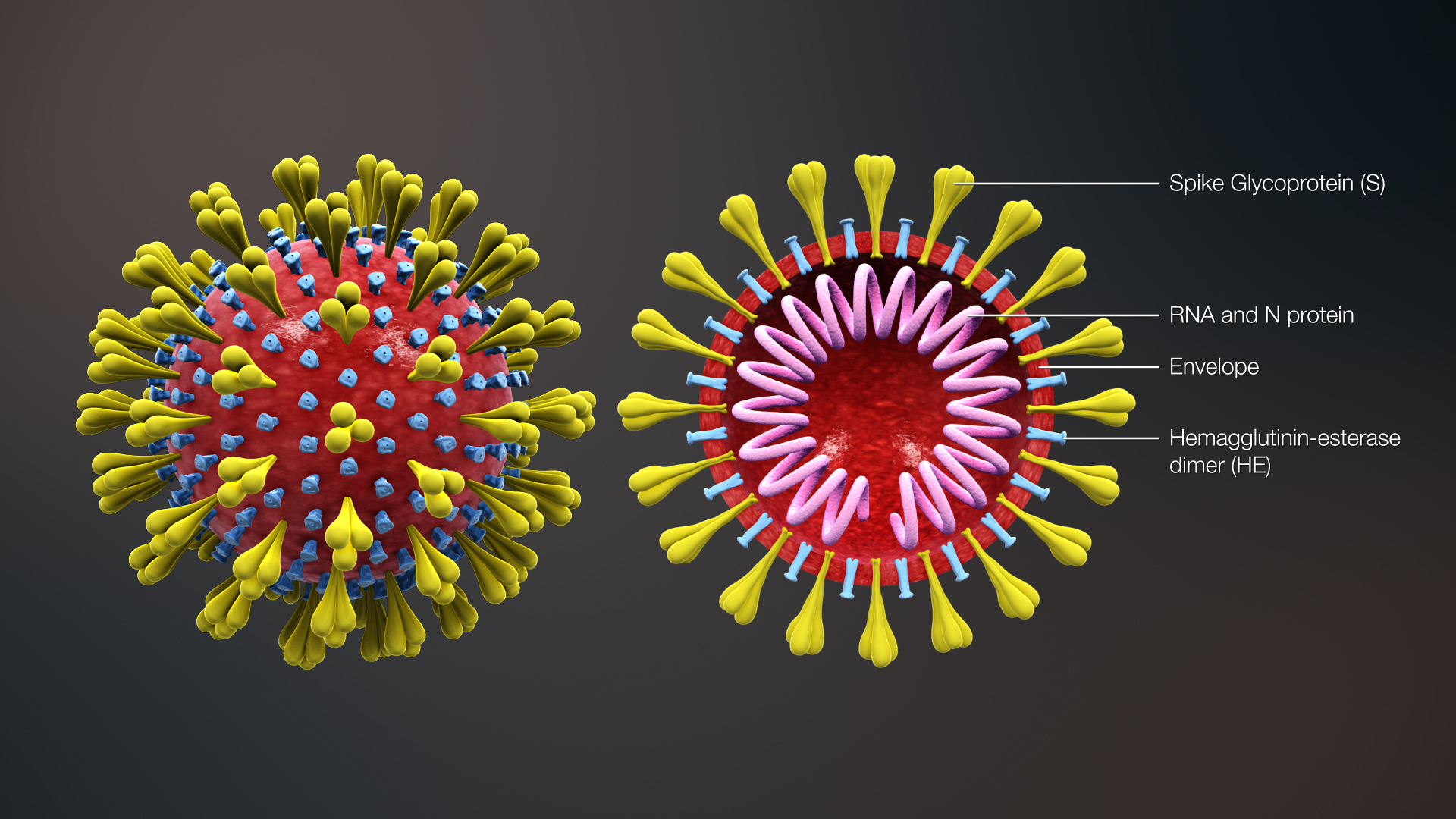

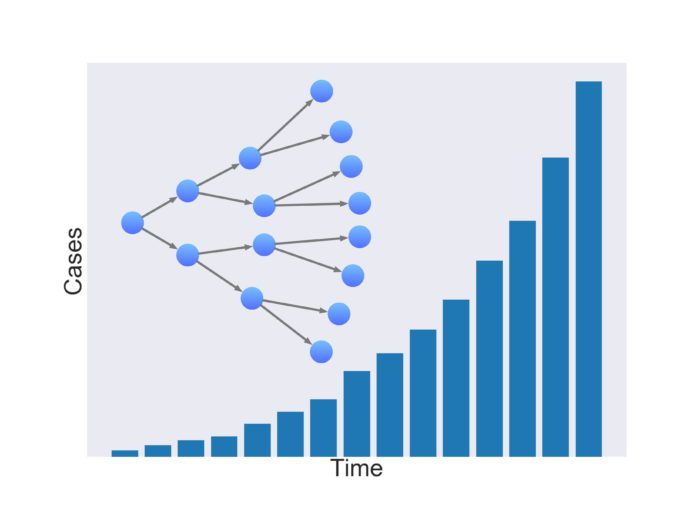

COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, is a challenge for everyone.

We know positive social support can improve our capacity to cope with stress. But right now we’re being asked to keep our distance from others to minimise the spread of the virus.

Many people are facing periods of enforced isolation if they are believed to have COVID-19 or have been in contact with someone who has.

Even those of us who appear to be healthy are being directed to practise social distancing, a range of strategies designed to slow the spread of a disease and protect vulnerable groups from becoming infected.

Among other things, this means when we’re around others, we shouldn’t get too close, and should avoid things like kissing and shaking hands.

This advice has seen the cancellation of large events of more than 500 people, while smaller groups and organisations have also moved to cancel events and regular activities. Many workplaces with the capacity to do so have asked their staff to work from home.

While it’s crucial to slowing the spread of COVID-19, practising social distancing will result in fewer face-to-face social interactions, potentially increasing the risk of loneliness.

Humans are social beings

Social distancing and self-isolation will be a challenge for many people. This is because humans are innately social. From history to the modern day we’ve lived in groups – in villages, communities and family units.

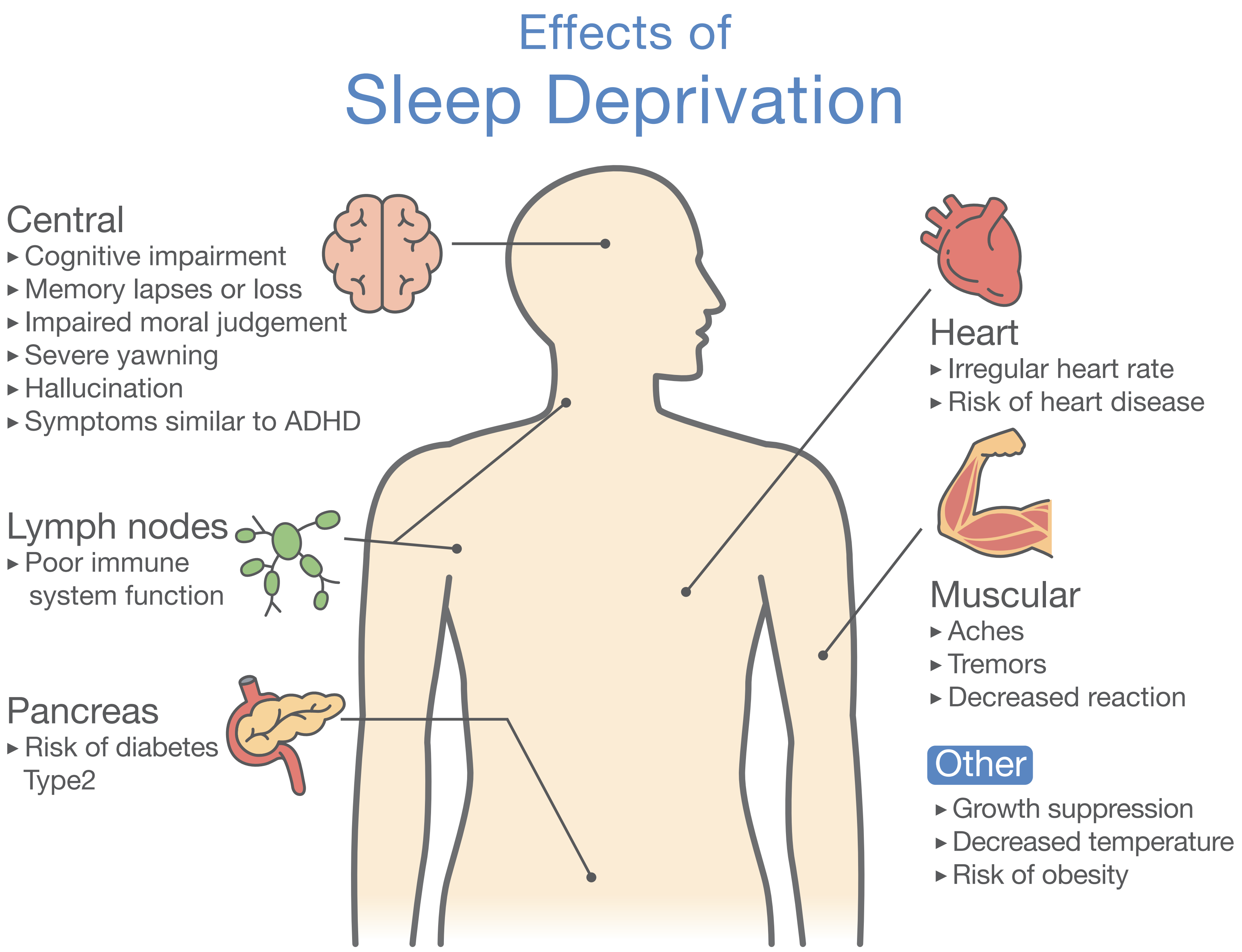

While we know social isolation has a negative impact on health, we don’t really know much about what the effects of compulsory (and possibly prolonged) social isolation could be.

But we expect it could increase the risk of loneliness in the community. Loneliness is the feeling of being socially isolated.

Recent reports have indicated loneliness is already a significant issue for Australians, including young people.

Loneliness and social isolation are associated with a similar increased risk of earlier death: 26% and 29% respectively compared to someone who is not lonely or socially isolated.

Read more: 1 in 3 young adults is lonely – and it affects their mental health

People who are socially vulnerable, such as older people, are likely to struggle more through this uncertain period.

If older adults are forced to self-isolate, we don’t have contingency plans to help those who are lonely and/or have complex health problems.

While we can’t replace the value of face-to-face interactions, we need to be flexible and think creatively in these circumstances.

Can we equip older people with technology if they don’t already have access, or teach them how to use their devices if they are unsure? For those still living at home, can we engage a neighbour to check in on them? Can we show our support by finding the time to write letters, notes, or make phone calls?

Supporting each other

Research shows a period of uncertainty and a lack of control in our daily lives can lead to increased anxiety.

In times like this, it’s essential we support one another and show compassion to those who need it. This is a shared experience that’s stressful for everyone – and we don’t know how long it’s going to go on for.

Fortunately, positive social support can improve our resilience for coping with stress. So use the phone and if you can, and gather a group of people to stay in touch with.

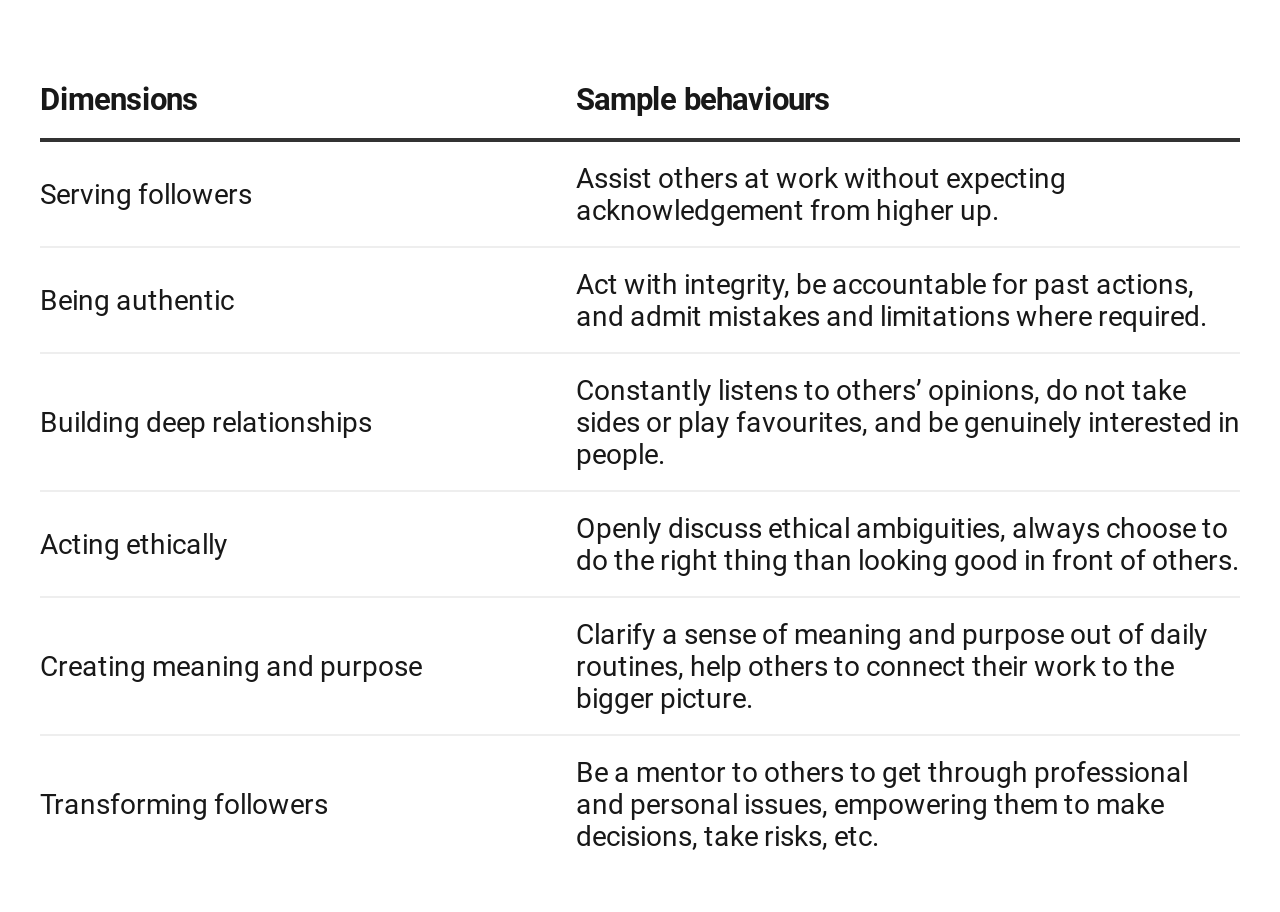

Further, positive social interactions – even remotely – can help reduce loneliness. Showing genuine interest in others, sharing positive news, and bringing up old memories can enhance our relationships.

Staying connected

Here are some tips to remain connected when you’re practising social distancing or in quarantine:

-

think about how you can interact with others without putting your health (or theirs) at risk. Can you speak to your neighbours from over a fence or across balconies? We’ve seen this in Italy

-

if you have access to it, use technology to stay in touch. If you have a smartphone, use the video capabilities (seeing someone’s facial expressions can help increase connection)

-

check in with your friends, family, and neighbours regularly. Wherever you can, assist people in your life who may be more vulnerable (for example, those with no access to the internet or who cannot easily use the internet to shop online)

-

spend the time connecting with the people you are living with. If you are in a lockdown situation, use this time to improve your existing relationships

-

manage your stress levels. Exercise, meditate, and keep to a daily routine as much as you can

-

it’s not just family and friends who require support, but others in your community. Showing kindness to others not only helps them but can also increase your sense of purpose and value, improving your own well-being.

Read more: Coronavirus is stressful. Here are some ways to cope with the anxiety

So get thinking, take considered action, and be creative to see how you can help to minimise not only the spread of COVID-19, but its social and psychological effects too.

– ref. Social distancing can make you lonely. Here’s how to stay connected when you’re in lockdown – https://theconversation.com/social-distancing-can-make-you-lonely-heres-how-to-stay-connected-when-youre-in-lockdown-133693