Analysis by Keith Rankin.

The most important measure of the favourability or otherwise of the international economic environment is called a country’s ‘Terms of Trade’. This label essentially means ‘barter price’, reflecting that international trade is essentially one country’s barter with the rest of the world.

(Digression. We note that such ‘barter’ is rarely the simultaneous barter with which we usually associate that word; whereby in a single mutual exchange, swaps of agreed equal value are made. So, for any given country in any given year, the barter is rarely a swap of equal value between domestic [our] and foreign [their] goods. If, in any given year, a country receives [by agreed value] more goods and services than it gives up – ie imports more than it exports – then that country is either incurring a debt to the rest of the world, or spending a credit. This process of incurring debts and spending credits – or, from the other side of the ledger, of incurring credits and settling debts – is known as ‘intertemporal trade’; ie as trade over time. Trade between one country and the rest of the world is expected to balance in the long run, at least in theory; however, see my International Trade over time: gifts with strings, Evening Report 8 May 2025, which shows that this long-run balancing often doesn’t happen in practice. We also note that Donald Trump’s project is to upset this coherent barter process by separately accounting for trade between his country and each other country; Trump wants, in each year and for each country, either a perfect barter, or for the other country to get [to import] more by agreed value than it exports. Thus Trump wants the United States to build up indefinite trade credits with each and every country; meaning that, eventually, he wants each country to have permanently unsettled debts with respect to the USA. That perpetual accumulation of credits is what President Trump calls “making money”. It’s what economists call mercantilism. Historically, Netherlands is the country most notorious for its mercantilist approach to international commerce.)

The ‘terms of trade’ does not measure the balance of trade. Rather, it is a measure of what a given amount of exports will buy. Thus, ‘favourable’ terms of trade are when $1,000,000 of exports will buy many imports. And adverse terms of trade are when $1,000,000 of exports will fund a relatively small quantity of imports.

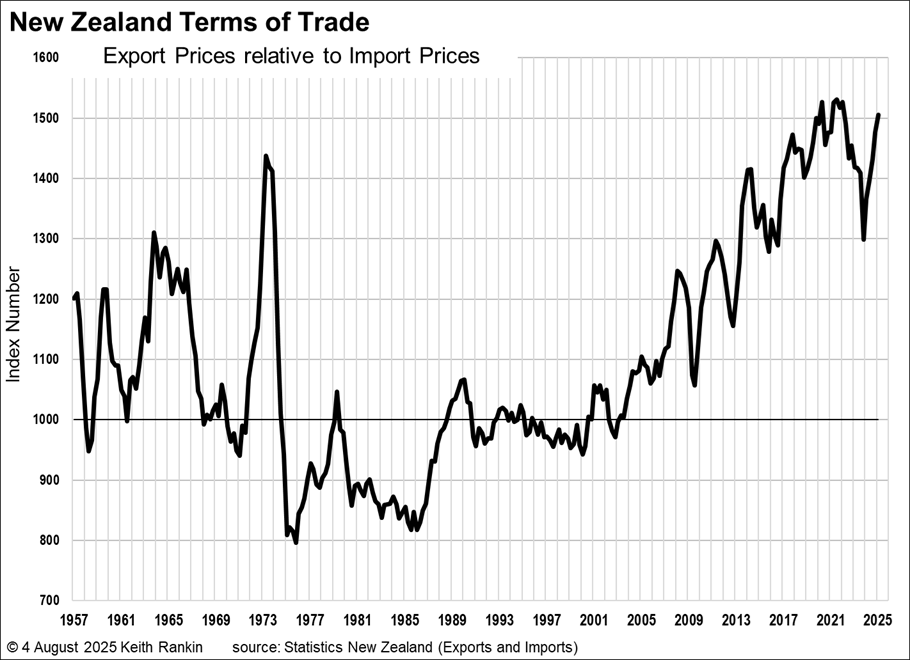

The chart above shows that Aotearoa New Zealand is currently enjoying near-record favourable terms of trade. At least with respect to New Zealand’s economic position in the world, New Zealand is currently enjoying the best of times. (And Donald Trump’s shenanigans in the United States will barely put a dent in this serendipitous state of affairs for New Zealand.) Indeed, when the Terms of Trade data for the June quarter of 2025 is released next month, New Zealand may have achieved a record-high terms of trade; the present covid-induced record high (from 1957, the year the data from Statistics New Zealand commences) is late 2021.

This year, if a terms-of-trade measure of 1000 is seen as neutral, then we are at present fifty percent above neutral, meaning our exports will buy fifty percent more imports than they would have bought under neutral – eg 1990s’ – international conditions.

We may note that from a perspective of 1985, New Zealand was ‘suffering’ a long-term decline in its terms of trade, indicating a need for economic diversification. But over the last 40 years, the whole lives-to-date of most living New Zealanders today, New Zealand has enjoyed a secular (albeit fluctuating) rise in its terms of trade; a persistent rise of its average living standards. This is not because of diversification; it is indeed despite diversification, and because the diversification of New Zealand’s tradable economy since the 1980s has been somewhat limited.

We can look back over this chart, and observe the good times and the bad times; noting that these good times and bad times have reflected New Zealand’s position in the ‘stormy seas’ of international commerce.

The terms of trade are only minimally affected by the economic policies of the day. The main reason for the improvement of New Zealand’s terms of trade since 2000 would be the rising living standards of the growing middle classes of the developing world (ie of the ‘global south’).

The terms of trade have contributed to many of New Zealand’s election results. A declining ‘terms of trade’ during election year would increase the likelihood of a change of government in New Zealand.

I’ll just make three further comments about the history.

First, the drops in 1974 and 1979/80 reflect geopolitical crises in southwest Asia – the Arab-Israeli War of 1973, and the Iranian Revolution of 1979 – and their impacts on world oil prices. Conversely, the rebound from 1986 reflects the resolution of the economic consequences of those crises, with substantial real falls in the price of oil.

Second, in the 1960s, the timing of the terms of trade fluctuations tended to reflect the timing of British general elections (meaning the relatively generous fiscal policies of the British government in the lead up to those elections, leading to more British consumer spending): 1959, 1964, 1966, 1970. (We note that, in the absence of such policies in 1970, the British Labour Government lost an election it was expected to win. And the new Conservative Government pursued unusually generous fiscal policies soon after it came into being.) The United Kingdom joined the European Economic Community (now the European Union) in 1973. Before then, it was the British market that largely determined New Zealand’s terms of trade.

Third, New Zealand economists used to take a keen note of the terms of trade, as a key economic barometer. This century, the ‘terms of trade’ only rarely becomes a point of public discussion about ‘the economy’. This reflects an increased (and somewhat misplaced) academic emphasis on government policy as a determinant of New Zealand’s economic success or otherwise. And a reflection of the unwillingness of New Zealand’s progressive and conservative elites to facilitate a sharing of the gains arising from New Zealand’s favourable terms of trade.

______________

Keith Rankin (keith at rankin dot nz), trained as an economic historian, is a retired lecturer in Economics and Statistics. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand.