Analysis by Keith Rankin.

Demographic information is starting to filter through again, after a slowdown in the Northern Hemisphere. And New Zealand now has reliable mortality data up to the end of July 2022. Australia continues to lag.

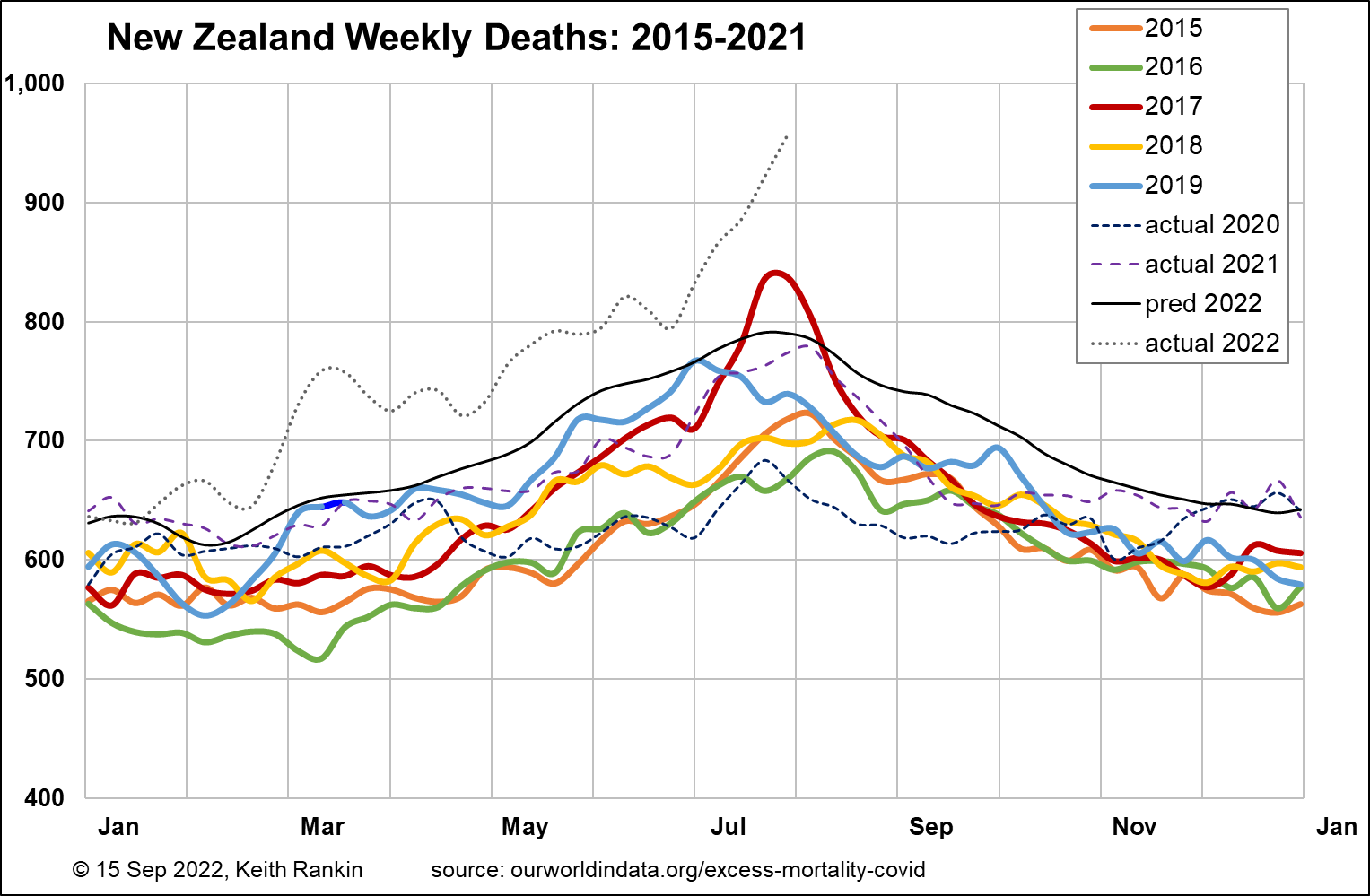

In the last week of July, New Zealand reached a record number of deaths in a single week; at least a record for the years since World War One. Those 957 deaths represent a 50% excess above the January to March low-mortality baseline. This puts our peak deaths in New Zealand’s ‘year of covid’ at above the huge influenza peak of 2017; and this peak follows a disastrous autumn.

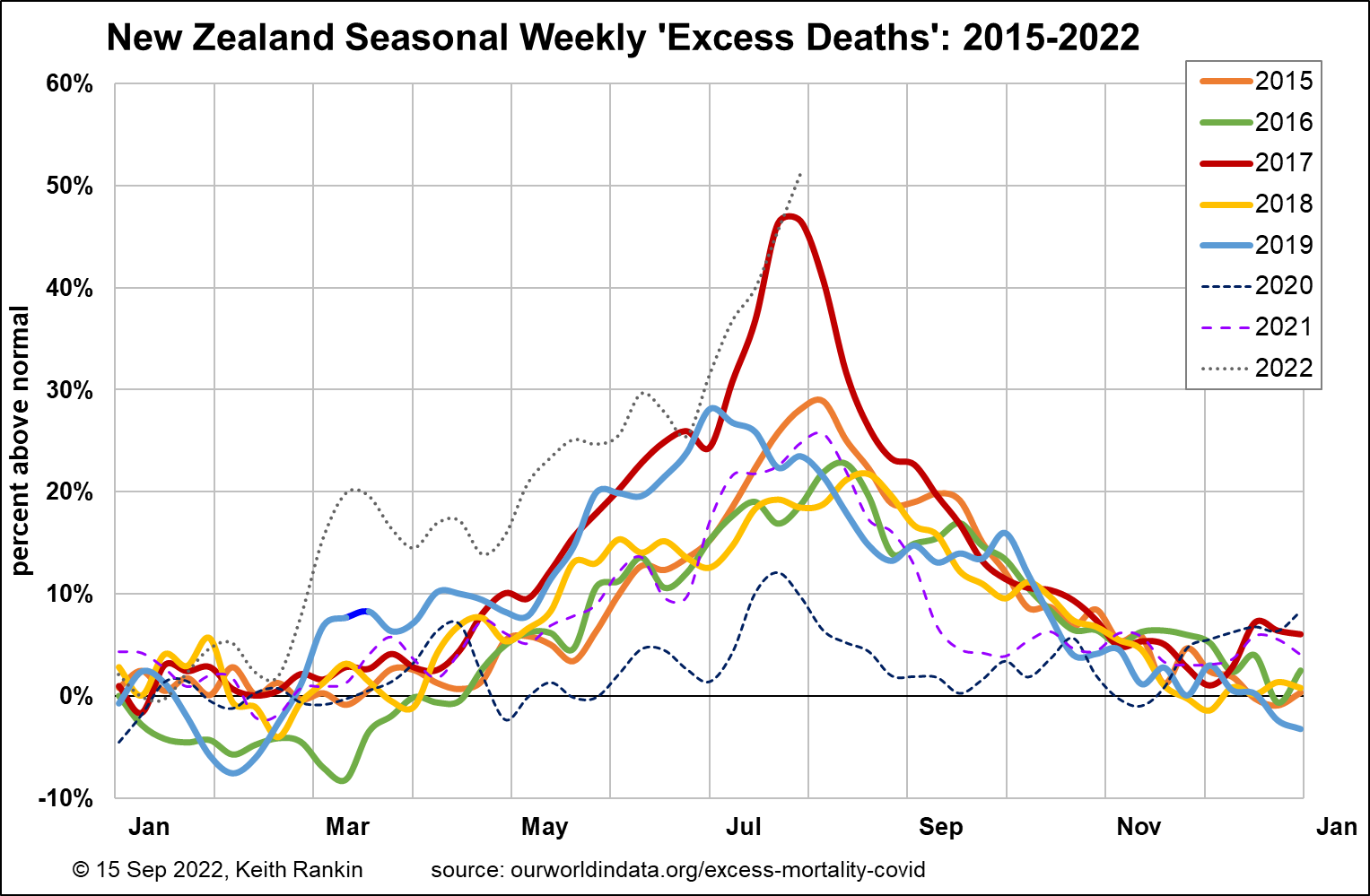

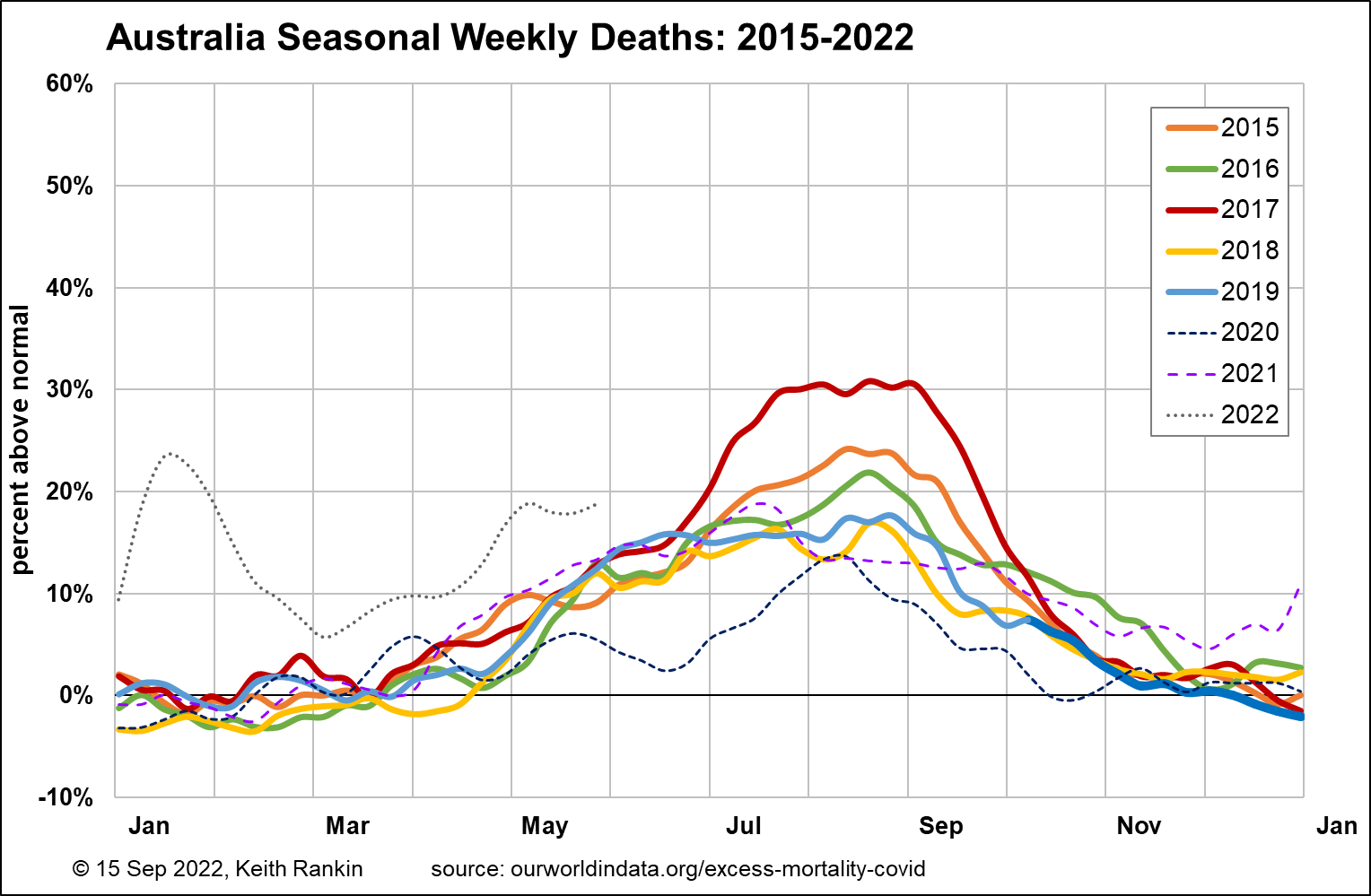

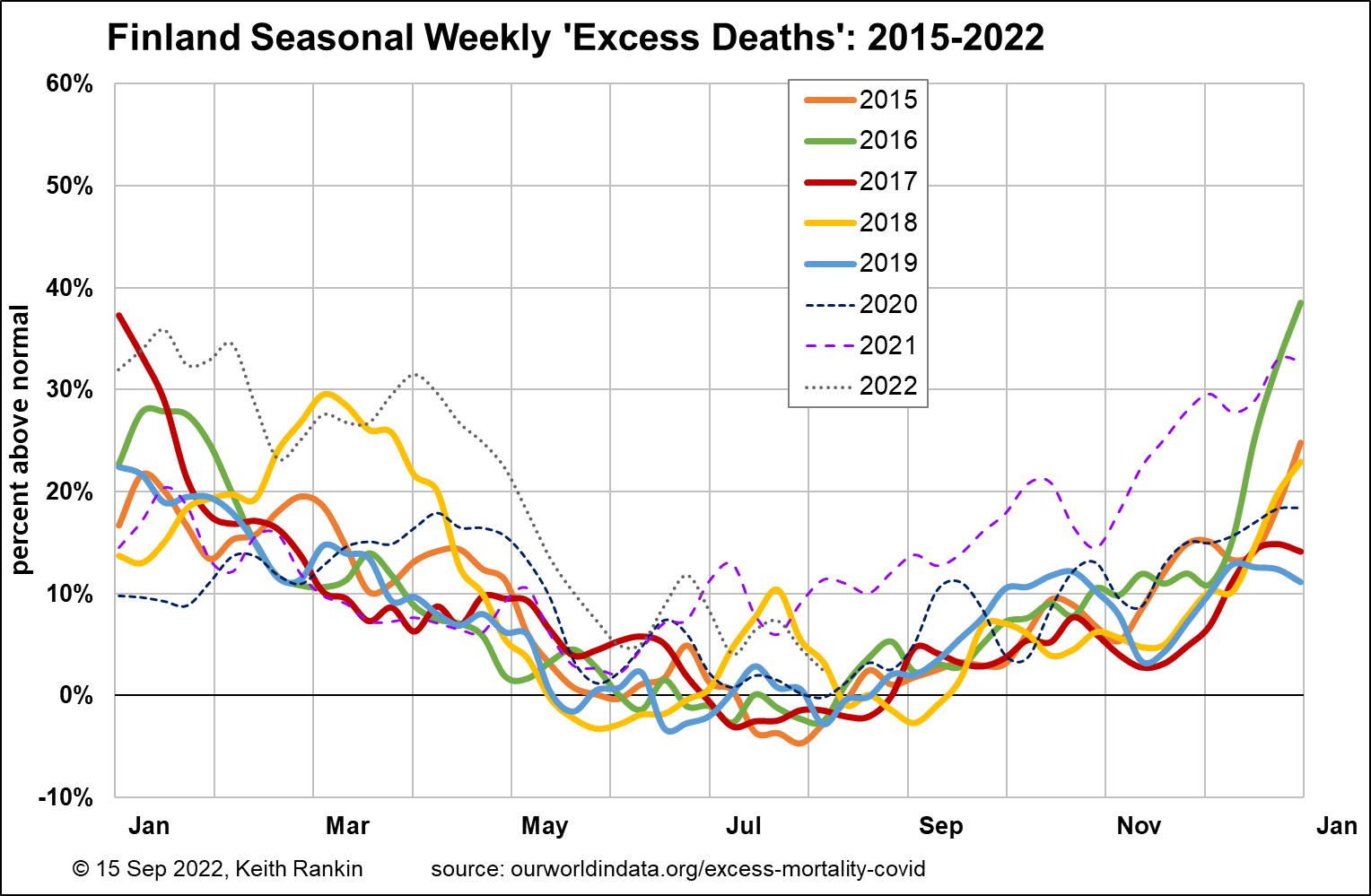

Comparisons

The four charts below all follow the same scale, allowing for excess seasonal and epidemic deaths to range from -10% to +60% of ‘baseline’ deaths. We note that, in most countries, the (unseen) baseline moves due to both general increases in the population and due to aging populations. The chart above includes the projection for 2022, based on pre-pandemic data. It shows a summer baseline for 2022, of about 630 weekly deaths.

We also note that, in additional to seasonal and epidemic mortality, any chronic increases in mortality from 2020 – ie non-seasonal nor epidemic deaths – will also show up, given that baseline estimates are drawn from 2015 to 2019 data. A slight flaw in the analysis – ie something not corrected for – is diminishing population growth from 2020 resulting from reduced immigration, reduced birth rates, and from the covid toll. Indeed, in some countries Covid19 may be reversing pre-covid aging trends (especially in Eastern Europe and Latin America where many older people have died, and from where youth emigration has decreased).

In Australia, the 2017 influenza peak lasted longer, though was less ‘peaky’. This is typical of a larger country, where different regions naturally peak at different times. Australia is likely to sea a 2022 peak of excess deaths between 30% and 40%.

Finland is a good country to compare with New Zealand, because it has the same size population, and because its government tried very hard to keep Covid19 out for as long as possible. Finland has two influenza peaks, comparable with New Zealand and Australia in 2017. And Finland’s covid peak of 35% is likely to be the same height as Australia’s. Of particular significance is its long mortality tail in the spring of 2022; and also the significant and sustained excess covid mortality in the autumn of 2021. My expectation is that Finland, as a good lead indicator so far for New Zealand and Australia, will continue to be a good predictor for us ‘down-under’.

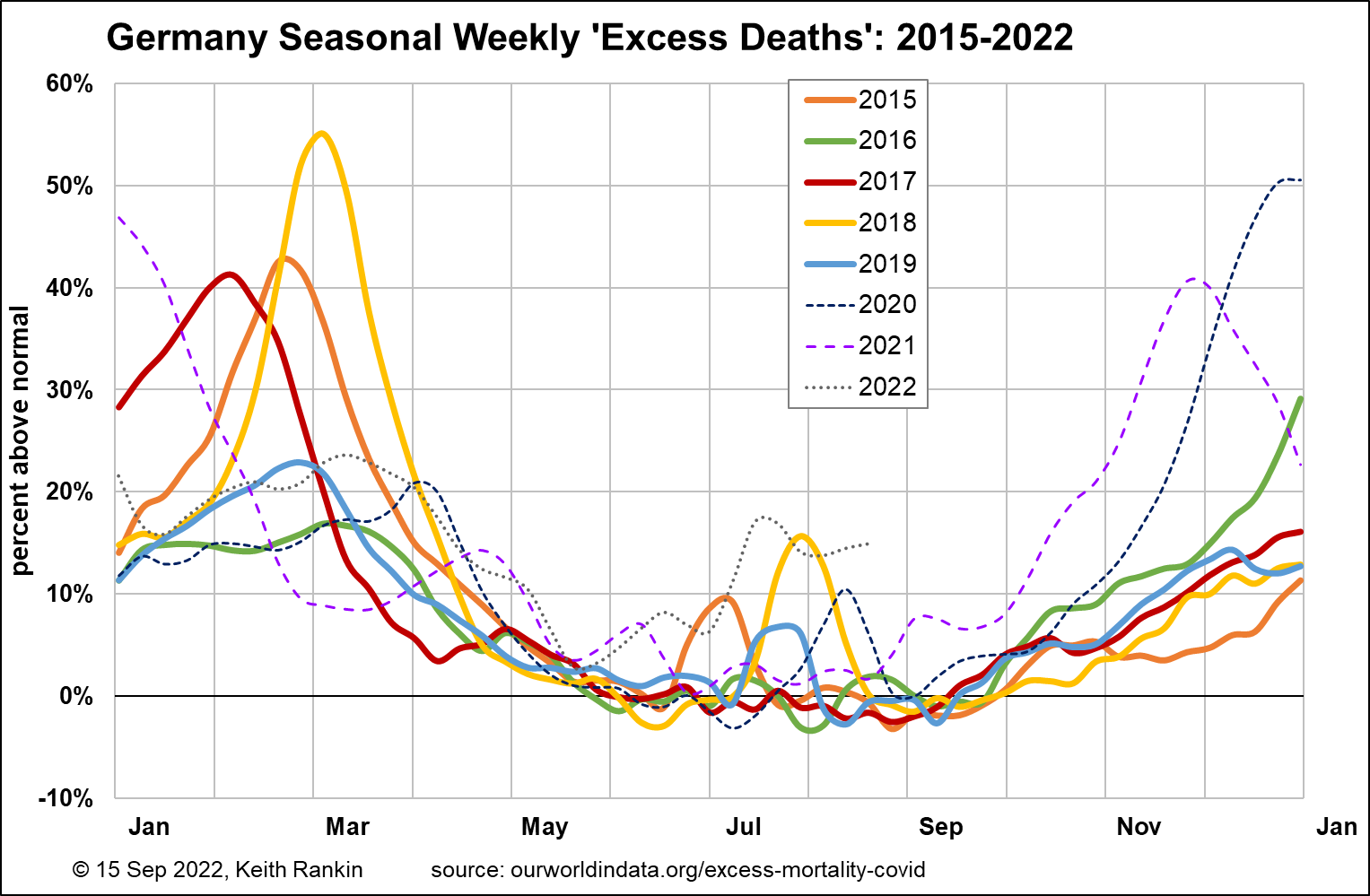

Germany is also interesting, with none of its covid epidemic outbreaks as ‘high’ as its influenza peak; though its covid peaks have been wider than its influenza peaks, as well as being earlier in the season (ie late autumn rather than winter). (The winter downturns will have ben due to public health mandates.) Germany, however, has a history of summer mortality outbreaks. This year, summer excess mortality is starting to look more chronic. One way or another, baseline mortality in Germany is itself rising in the wake of the pandemic.

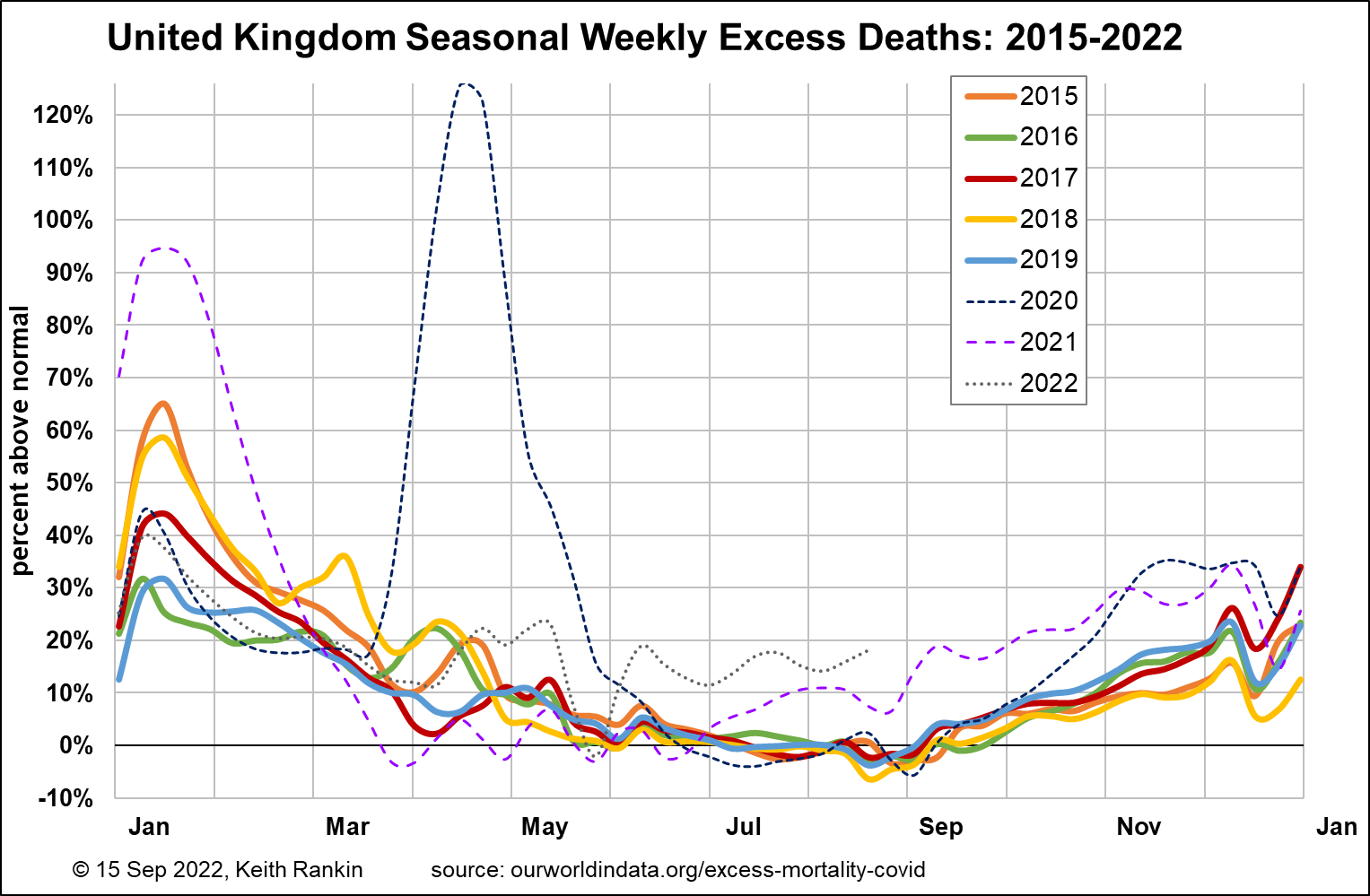

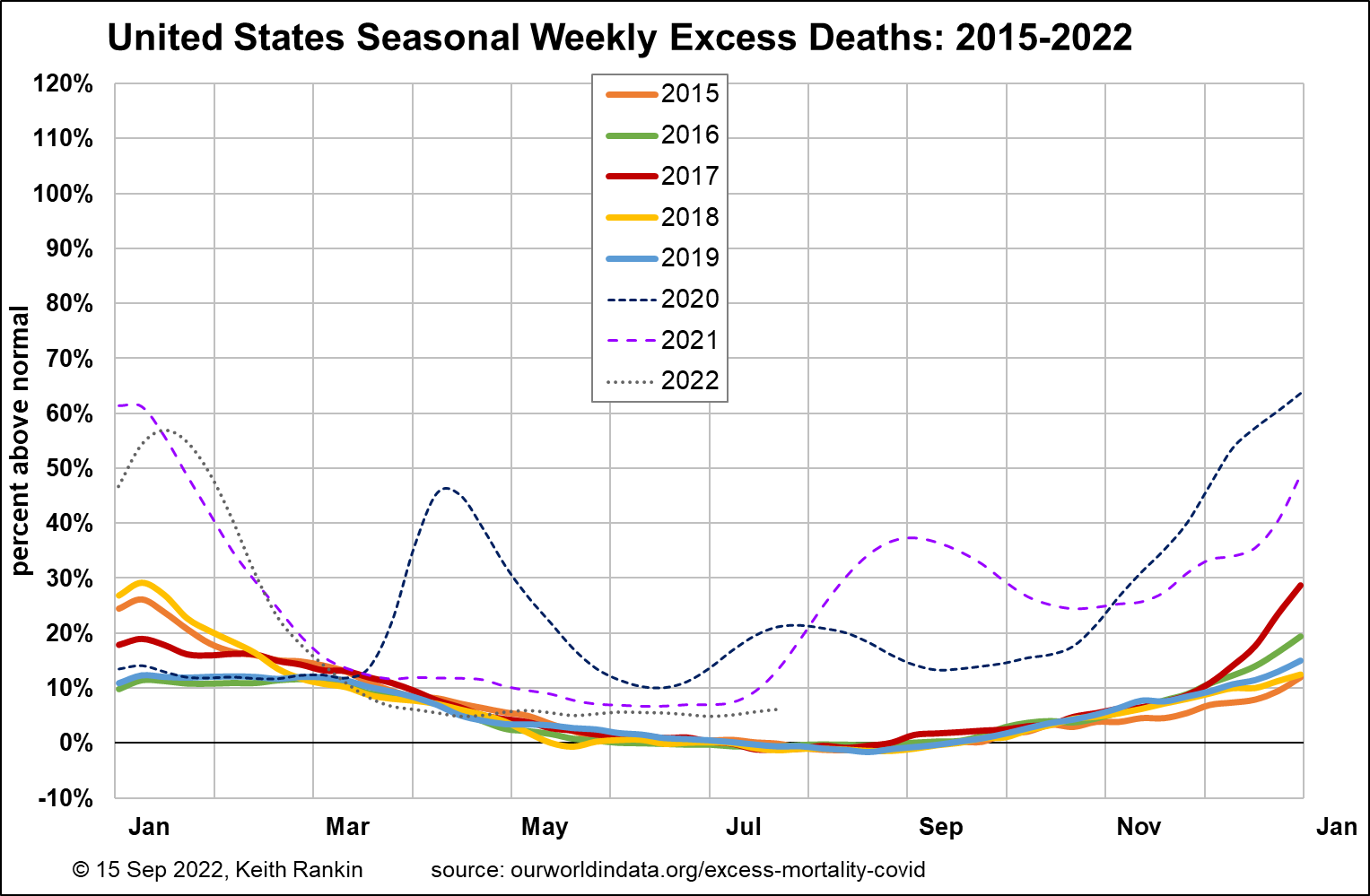

I finish with United Kingdom and United States, which require a different scale mainly due to the United Kingdom’s initial covid outbreak in early 2020.

In the United Kingdom we see particularly high influenza peaks in the Januarys of 2015, 2017 and 2018. The winter covid peak of 2021 had that same timing, and reached 95% of excess deaths (ie excess compared to summer). From March 2021, however, we see nothing in excess of 40%. Though we do sense an emergent pattern of chronic autumn mortality, comparable with Germany.

The United States has updated its recent mortality statistics, now showing a summer excess of around 6%. This may prove to continue into the autumn, in line with what appears to be happening in Germany and United Kingdom. The peaks in the United States are not nearly as high as those of the United Kingdom, reflecting its larger size and more dispersed population. Instead of being high, the American peaks of seasonal and epidemic mortality are wide, resulting in more overall excess mortality there than in the United Kingdom.

2020 does appear to represent a demographic turning point in these countries, and probably in the world as a whole. New Zealand should not be too self-congratulatory; the mortality patterns we are now seeing are not exceptional, only delayed by two years. (Even 2021 in New Zealand is concerning; normal seasonal mortality took place despite some particularly strong public health restrictions. 2021 was a year with few covid or influenza deaths. So what were people dying of?)

*******

Keith Rankin (keith at rankin dot nz), trained as an economic historian, is a retired lecturer in Economics and Statistics. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand.