Analysis by Keith Rankin.

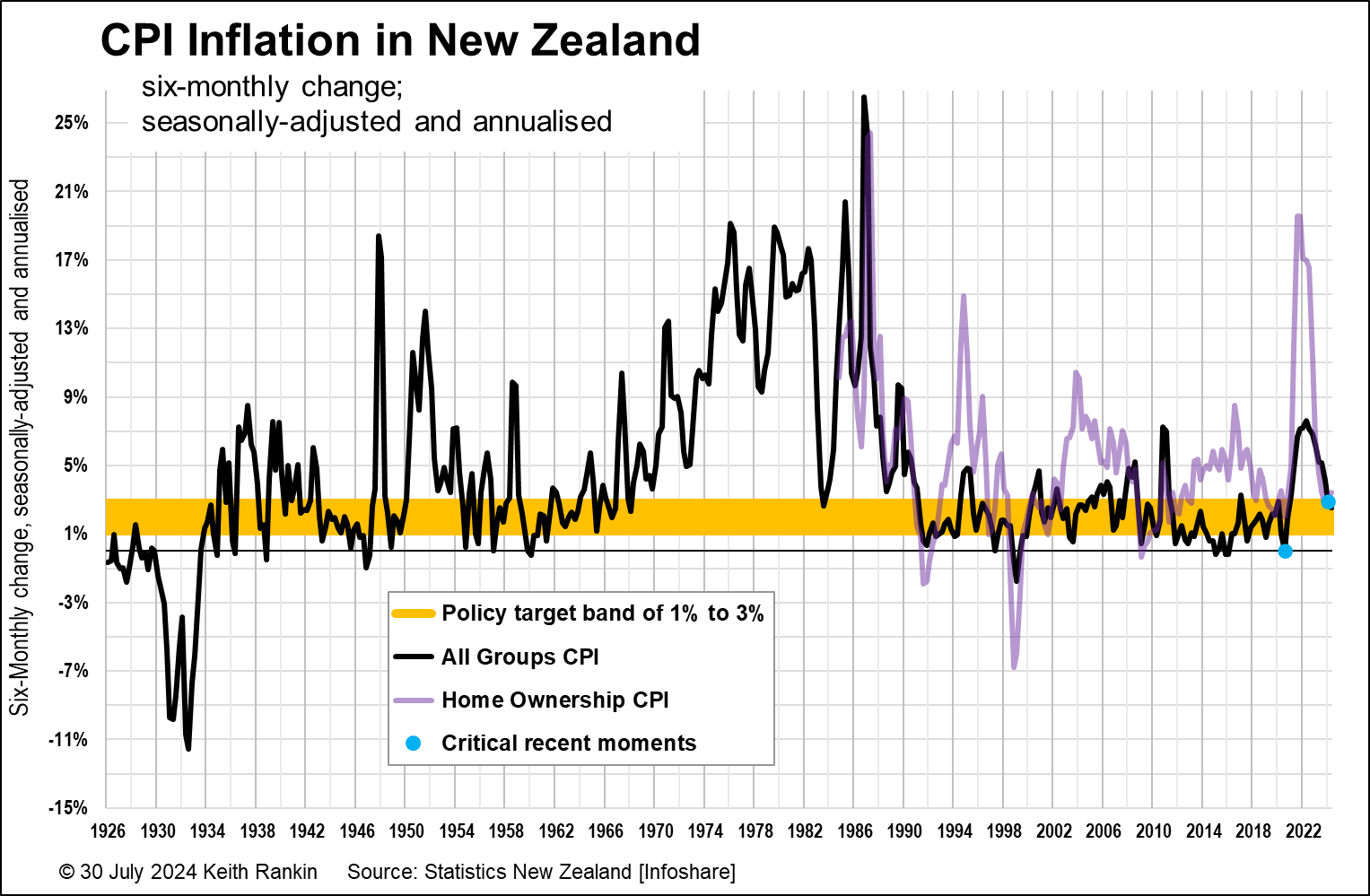

The above chart shows CPI inflation in New Zealand in historical context. The chart shows (in orange) the present policy target band of one to three percent annual inflation. And it shows the ‘home-ownership’ component of the CPI.

The chart looks different to most charts of CPI inflation, because it uses seasonally-adjusted price comparisons over a six-month period, rather than over a 12-month period. These biannual price increases are then ‘annualised’, so that the numbers are scaled to the annual percentages we are familiar with.

The making of this chart was triggered by me reading a NZ Listener editorial ‘House of the rising sum’, from 28 November 2020. The context is that some economists were arguing, even then, that the Reserve Bank should have started raising interest rates in the latter part of 2020.

The Reserve Bank has mandates to manipulate interest rates and monetary quanta in order to keep CPI inflation within the orange band. (The Bank is also mandated to protect the integrity of the financial system, and this overriding provision was in play in 2020, as it was in 2008/09.)

The mantra goes that if the calculated CPI inflation rate is below the orange band then the Bank should cut interest rates, and that if above the orange band then the Bank should raise interest rates. (The mantra is basically a policy-vestige of the gold standard era – 1870s to 1914, 1926-1931 – which was revived in the monetarist 1980s and applied to a world with flexible exchange rates.)

The chart shows that, based on the inflation-interest mantra, late in 2020 (at the time of the Listenereditorial; see the first blue dot in the chart) that interest rates should not have been raised (and should perhaps have been cut, from 0.25% to 0% or 0.1%). There is certainly no mandate in favour of pursuing an anti-inflation policy at that time.

The chart also shows that CPI inflation in 2024 is within the orange band. (Refer to the second blue dot.) This means the Bank should be in an interest-rate cutting phase. Yet the bank hasn’t yet done a single cut. This failure to act in accordance with its mandate should be the subject of a major political conversation today.

Looking more broadly, we see that CPI inflation is typically ‘spikey’ in nature; quick to rise and quick to fall. Some of the biggest spikes are associated with the introduction of GST (Goods and Services Tax) in 1986/87 and the two occasions in which the GST rate was increased (1989, 2010).

The spikey nature of CPI inflation gives lie to the new-monetarist notion that inflation is driven mainly by expectations of inflation. If that was true, unacceptably high inflation rates would plateau until those expectations were bludgeoned out of our psyches. (Yes, even the textbooks say that sound disinflationary monetary policy requires “credible” interventions, meaning that the bludgeon has to be seen to be being used, and that it will continue to be used until our alleged-beliefs conform with our required-beliefs. It’s like a credible torture policy, common in autocratic societies.)

The only times there were something close to inflationary plateaux in New Zealand were in the 1970s and the Korean War period of the early 1950s. The more recent plateau was essentially over in 1984, with two subsequent spikes being principally due to the short-lived devaluation of 1984, and the introduction of GST in 1986.

The introduction of the Reserve Bank Act, which formalised the present practice of monetary policy, took place well after the end of the 1970s’ inflation plateau. It was a policy to address a problem that did not exist then; though some will argue that the plateau of inflation did not end until after 1986. (The argument is that inflation would have been high in 1986 even if GST had not been introduced. I don’t think the data supports that interpretation; the 1986/87 spike looks to me like a classic tax spike.)

Two more points to note. The deflationary plateau of the early 1930s is the Great Depression. Deflation is a much bigger problem than inflation, and policy-making in 2020 appropriately had that message in mind.

The second point is that the purple line shows the urban real-estate price booms since 1984. In the 1980s and 1990s we see house price inflation spikes coinciding with general CPI spikes, although 1986/87 was also a tax-spike. In the 2000s we see (after the initial spike) a house price boom coinciding with a period of tight monetary policy – rising Bank-set interest rates and rising CPI inflation.

In the 2010s we see a similar house price boom coinciding with a period of unusually low interest rates. This tells us that neither high nor low interest rates are the dominant driver of real-estate inflation; something else is going on. The suggestion in the later 2010s was that the something-else was immigration. Yet immigration certainly was not the cause of the 2021 house-price spike. Mass immigration came after that spike.

The most recent house-price-spike most likely does have something to do with easy monetary policy lasting for nearly a year after the first blue dot. But it didn’t have to be that way. The Bank created extra money, contingency money; the course the pandemic was taking was highly uncertain. Newly created money was parked in the commercial banks instead of in the government’s coffers. Because the government was unwilling to borrow that money – even when the interest rates were near to zero – the money ended up sitting on the balance sheets of the commercial banks. The banks naturally found that the most profitable outlet was to push that money through the commercial banks into the housing market; increased business lending was neither possible nor appropriate at that time of great global uncertainty. Asking commercial banks to park money is like asking a fox to guard chickens.

CPI inflation spikes are a fact of normal economic life. Global events create price shocks. Normally the market-economy resolves these shocks quite quickly; and that’s what most of us expect to happen despite a few academic and bank economists telling us we have inflationary expectations whenever prices spike.

Autocratic monetary policy – a policy mantra through which central authorities override normal market-based resolutions – undermines normal market responses, and raises inflation expectations while claiming to be lowering them. High interest policies act as a tax on producers – precarious workers and precarious businesses – for the benefit of the top wealth decile, the ten-percenters. Far too much of our political conversation has been dominated by ten-percenters and their ‘west-wing’ world views; these are the people who refuse to contemplate that the interest rate inflation mantra might be flawed policy.

*******

Keith Rankin (keith at rankin dot nz), trained as an economic historian, is a retired lecturer in Economics and Statistics. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand.