Analysis by Keith Rankin.

The ‘Young Elderly’ are in essence the post-war baby-boomers. An average young elderly person in these charts was born around 1950 to 1952.

The charts look at ‘quarterly excess deaths’, so do not show week-by-week fluctuations in deaths. For example, data for the very end of 2022 covers the whole of the last three months of 2022.

As in my previous recent charts (see my Spiralling Deaths in Germany, Evening Report, 14 March 2023; and Examples of Germany and Denmark, Evening Report, 12 March 2023), I have emphasised Germany, because late-pandemic mortality has been so bad there. And because Germany’s differences with the rest of Europe create a very useful point for epidemiological analysis.

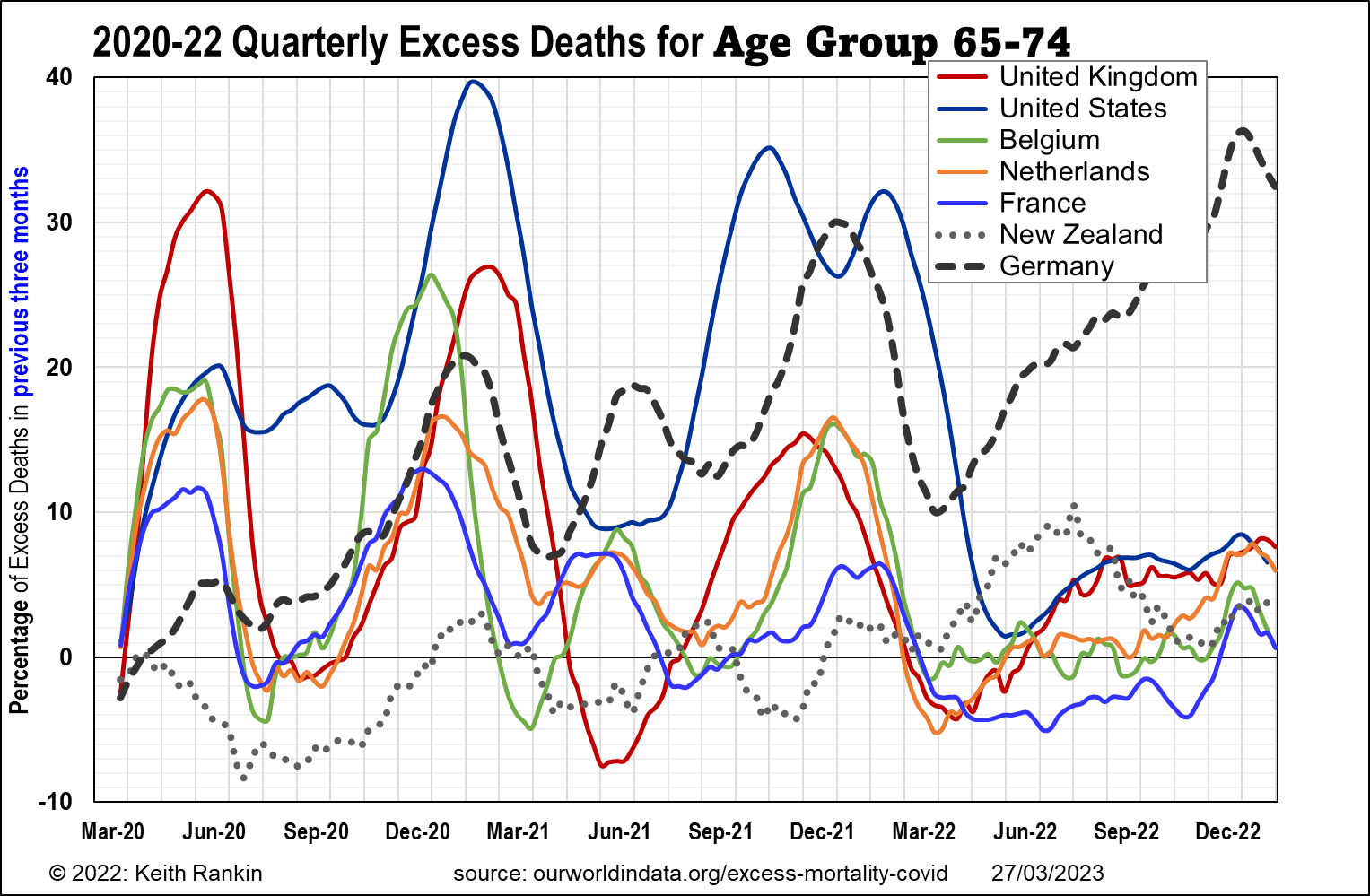

In the first chart (above), of the countries shown only Germany and New Zealand had excess deaths in this age group below ten percent in the first six months of Covid19. The United Kingdom was easily worst then.

The United States had a really bad pandemic, for two years from April 2020 to April 2022. But, subsequently, for nearly two years since April 2021 Germany has been for the most part easily the most deathly of these countries, for the young elderly, with only the USA contesting Germany for this dubious honour. For some of 2022, New Zealand was in second place out of these seven countries.

We note that Belgium, Netherlands and France all had high death rates early in the pandemic, but have subsequently had much lower death rates than Germany for this age group.

The two obvious avenues for investigation are diet (the French surely have a more healthy diet?) and differences in the policy responses to the Covid19 pandemic. My understanding is that, while all countries had similar public health restrictions during the peak weeks of Covid19, Germany was much the slowest of these countries to remove mandated public health measures. Germany’s abundance of caution may have backfired big-time. Yet the only reason given here (on Deutcshe Welle) is: “that diseases other than Covid19 are bouncing back because fewer people are wearing masks amid a general relaxation of pandemic rules in comparison with the past two years”. There is no hint of comparative analysis in this particular DW media report.

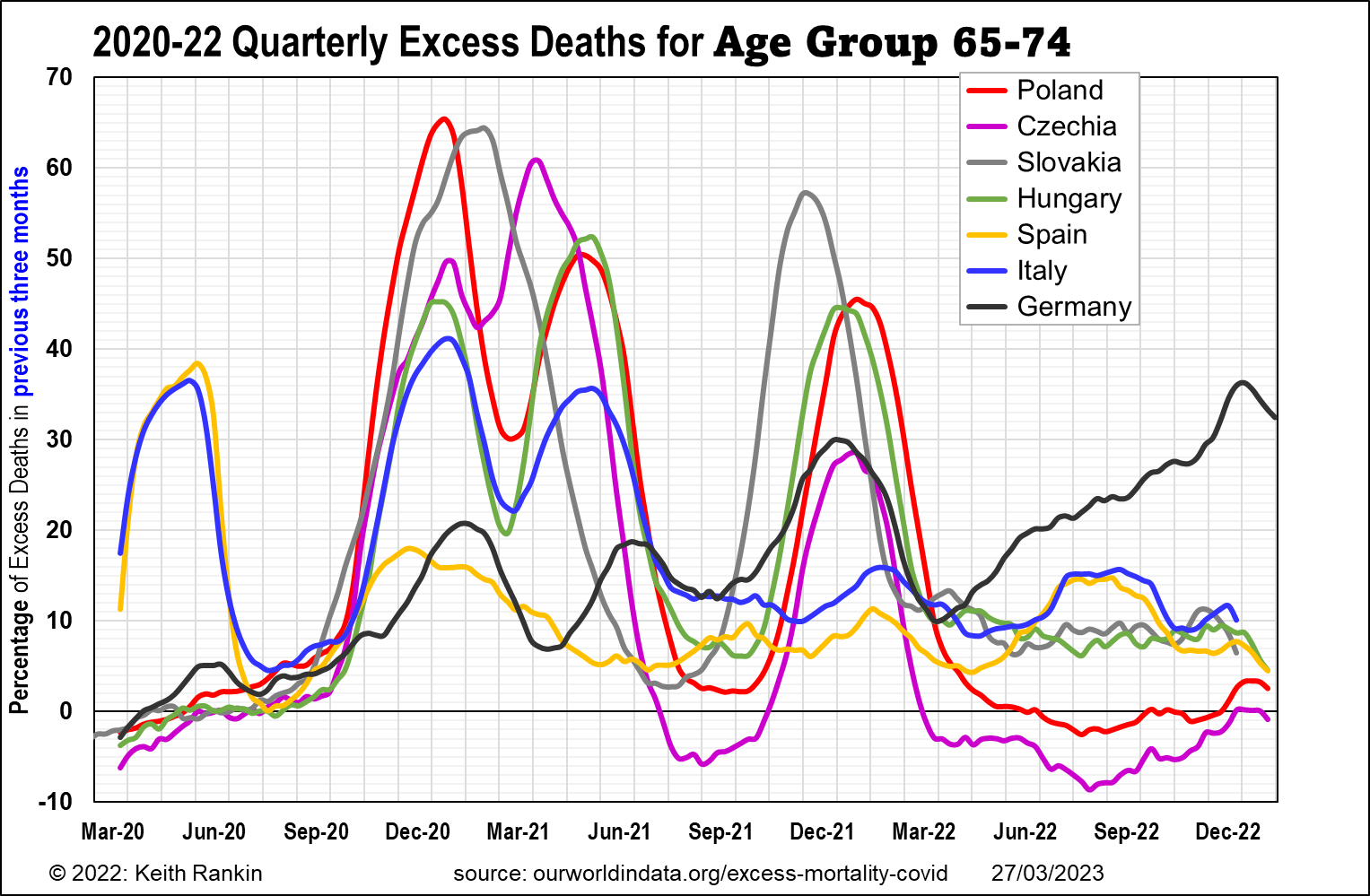

The second chart compares Germany with its four nearest Eastern European countries, and with the two Mediterranean countries which were the first to experience substantially elevated pandemic death rates.

For the young elderly ‘boomers’, Spain and Italy show quite the opposite pattern to Germany; they started with high death rates and then moved to generally lower rates. Both had summer mortality peaks in 2022, to some extent due to the summer heat waves but mainly due to the rebounding of tourism with Covid19 still present. Covid19 flourishes in bars and restaurants, and in airport terminals.

The eastern countries had more deaths overall in the middle seasons of the pandemic, despite (or maybe because of) the success of the measures taken in the early months of the pandemic. Also, for these countries, with lower life expectancies than their western neighbours, the young elderly are on average closer to their eventual deathdays. It is important to note that these eastern countries had the fewest pandemic-related deaths after March 2022. Presumably their people most at risk of dying had already died, and the remainder had higher natural immunity to respiratory illnesses than did the older citizenry of Germany. (I am not aware that Polish, Bohemian or Hungarian cuisine is particularly noted for its health benefits, in contrast to the much-touted Mediterranean diets; so a better diet is probably not the reason.)

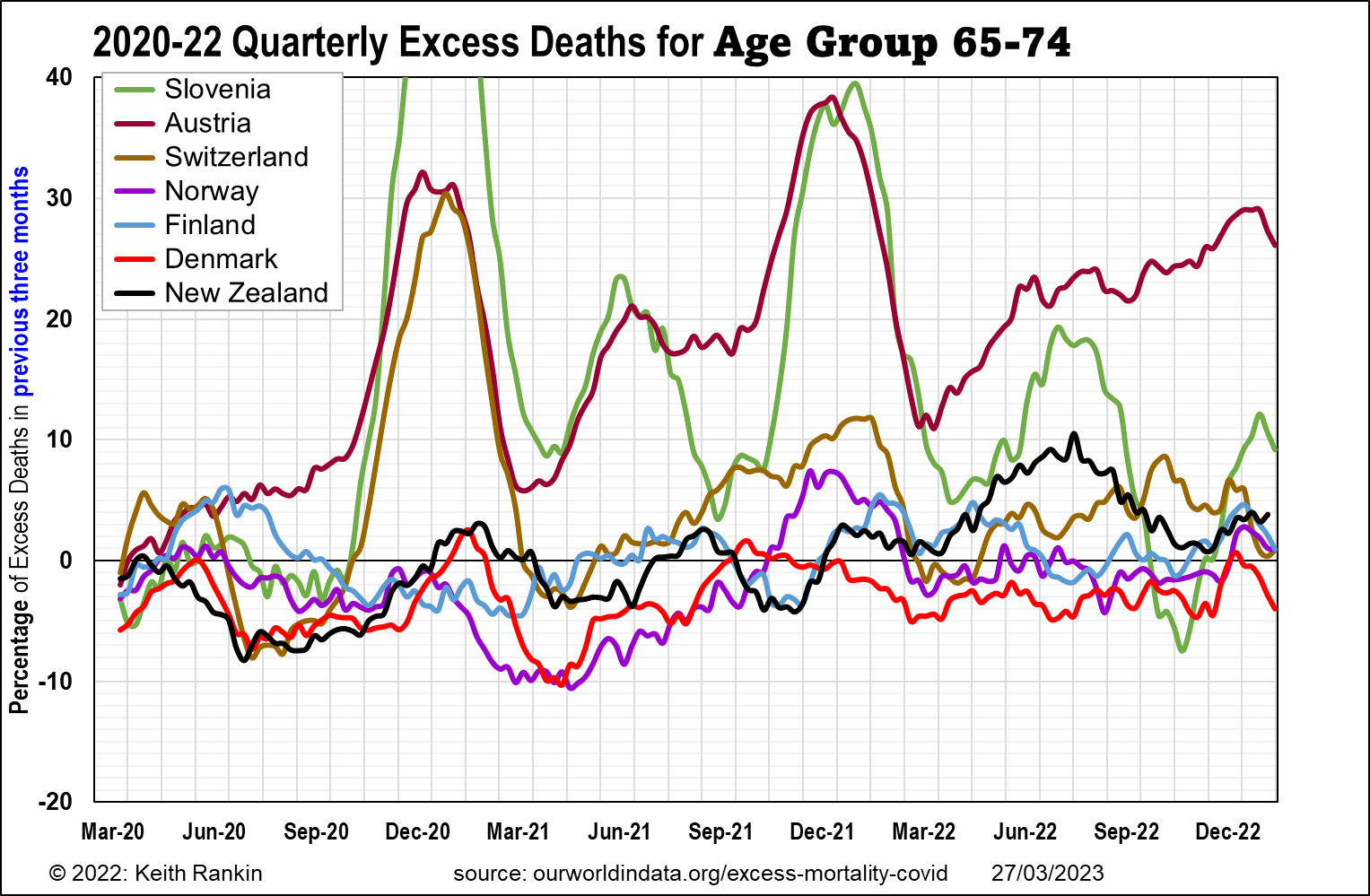

There is one other country with a similar pandemic death-profile to Germany; its southern geographic and cultural neighbour, Austria. The final chart here shows the smaller countries of western and central Europe, plus New Zealand. (Australia and Sweden do not provide age-group data.)

First we note that Austria and its neighbours Slovenia and Switzerland start out closely synchronised. Switzerland drops off Austria’s high young-elderly mortality path from March 2021, and Slovenia drops off a year later (though has a high summer peak in line with its Italian neighbour). The Scandinavian countries had generally low death rates for the young-elderly age group. (They did however see rising deaths from mid-2021 for the older elderly.)

Any valid epidemiological analysis for Germany’s 2022 tragedy needs to take into account the similar experience of Austria, as well as the generally different experiences of the other European and neo-European countries.

The United States still has a worse overall pandemic record than Germany, for the young elderly. The worry for Germany, though, is that the reasons for its really bad 2022 have not necessarily been resolved; 2023 may be just as bad. Time will tell; so long as an asteroid strike or a nuclear war don’t displace infectious diseases as drivers of excess mortality in Europe.

Keith Rankin (keith at rankin dot nz), trained as an economic historian, is a retired lecturer in Economics and Statistics. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand.

https://www.dw.com/en/winter-illnesses-burden-germanys-intensive-care-units/a-64135331

https://www.dw.com/en/top-german-virologist-says-covid-19-pandemic-is-over/a-64214994