Analysis by Keith Rankin.

Those countries which are most efficient at reporting demographic information now have complete deaths’ data for last year. Some information revealed is worth noting. (With the exception of Poland, further below, all countries’ charts have a scale of excess deaths ranging from -10% to +70%.) Most of these are countries that ‘performed’ well on Covid19 mortality in the first year of the pandemic, due in that year to public health mandates.

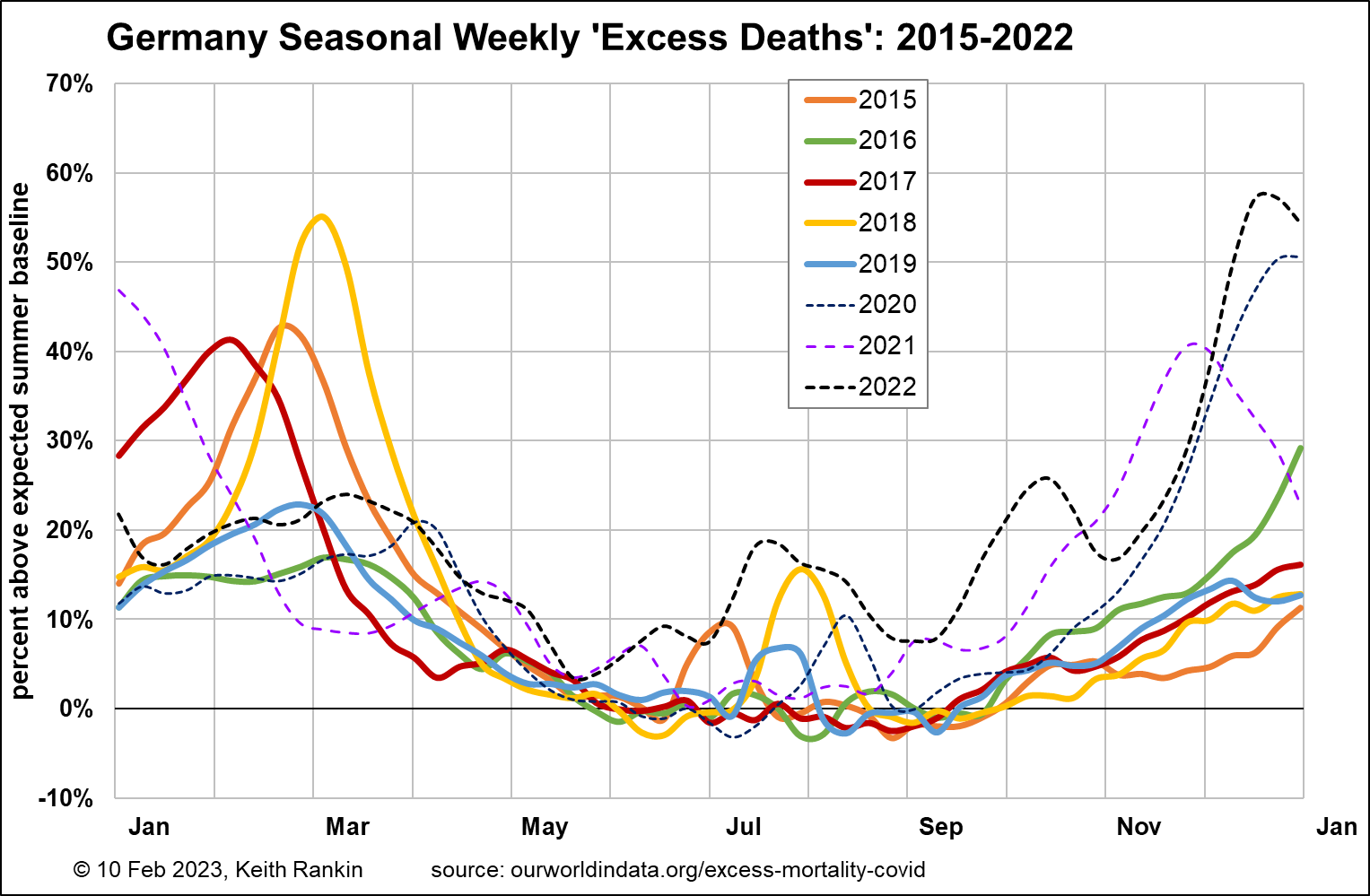

Germany experienced its worst ever wave (since 2015) of epidemic mortality at the very end of last year, even exceeding deaths in the big influenza outbreak of early 2018. More generally, 2022 was easily Germany’s worst year for pandemic-related mortality. We also note that Covid19 seems to be especially problematic in the late autumn months, whereas influenza has done its ‘killing’ mostly in the late winter. Germany also reveals smaller mid-summer mortality peaks which reflect the greater mingling of people from around the world.

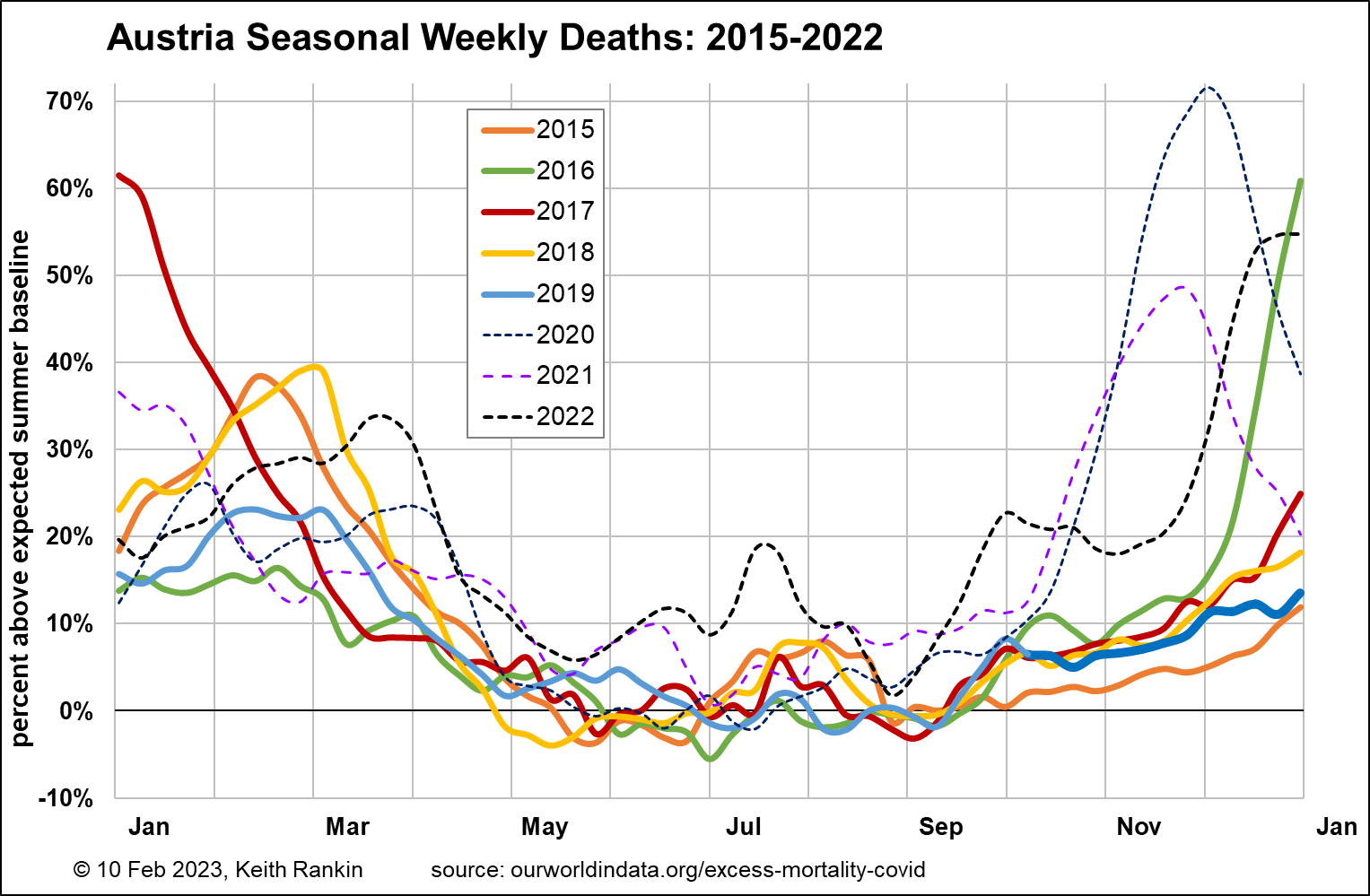

Austria shows epidemic death patterns similar to Germany, though slightly more accentuated (probably) due to Austria’s smaller population. Additionally, Austria suffered much more than Germany from the initial 2016/17 blast of the 2016‑2018 global influenza epidemic.

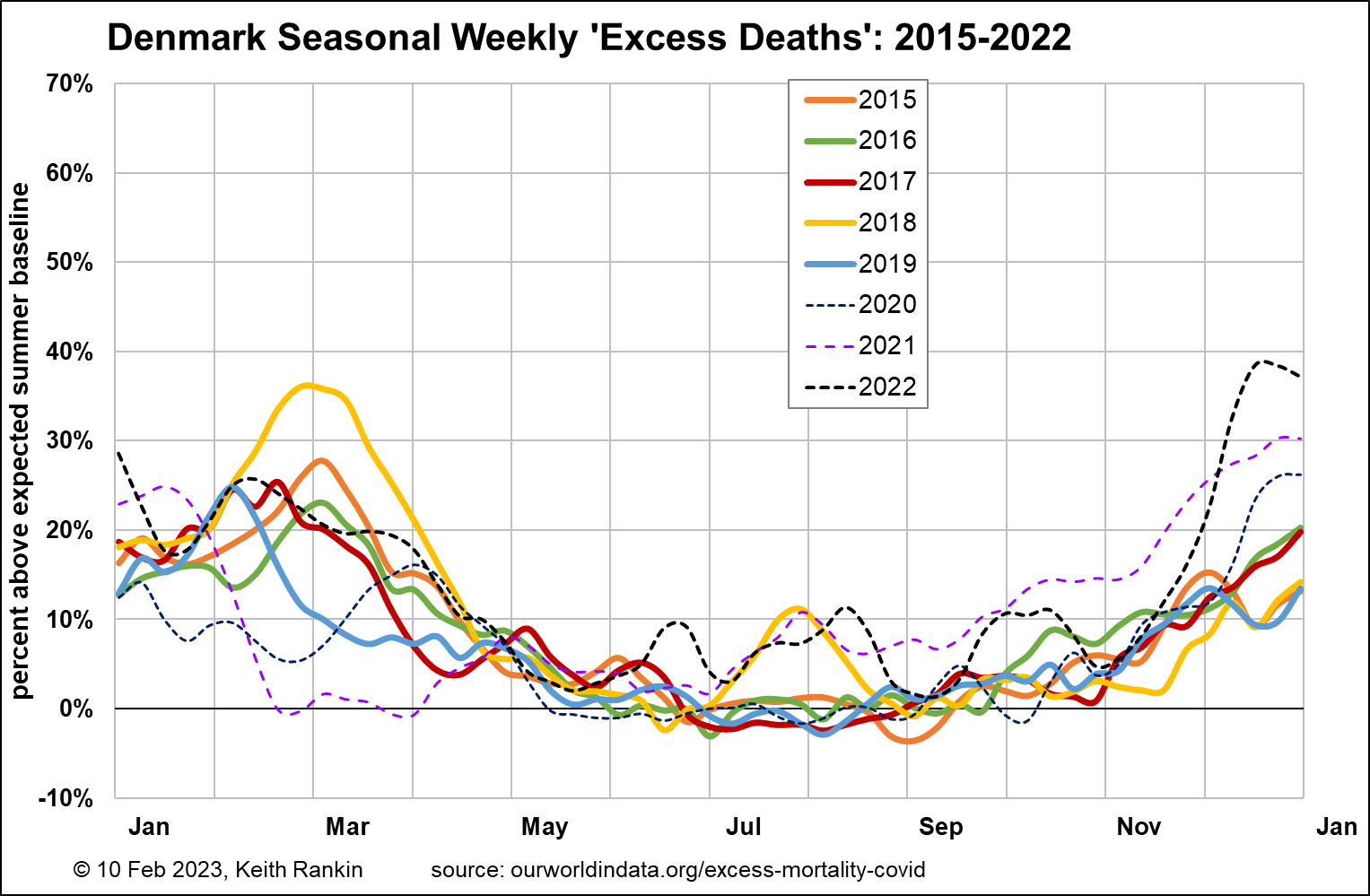

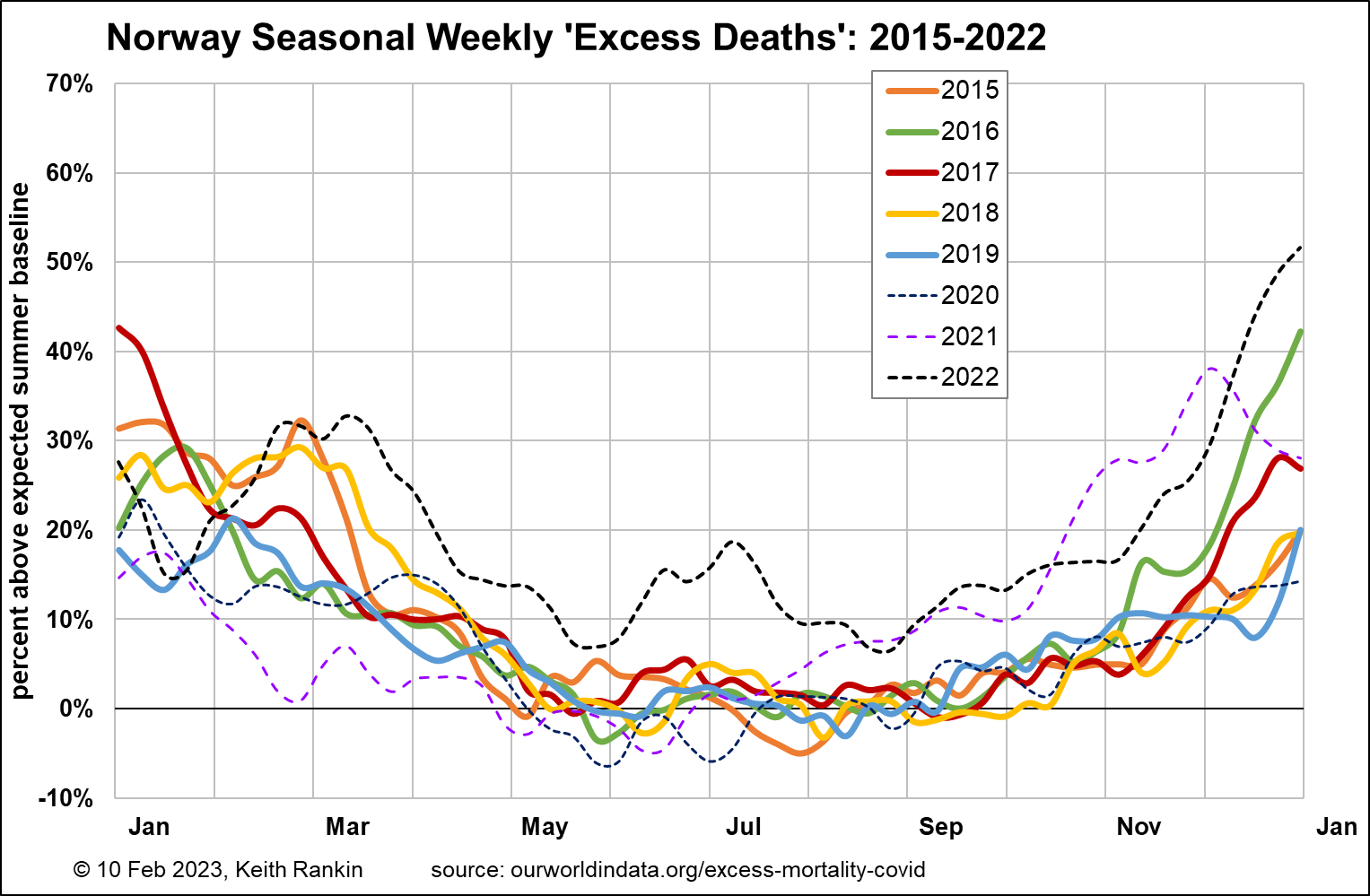

Denmark, as is the case with Scandinavia more generally, shows lower epidemic mortality in both the 2010s (influenza) and 2020s (coronavirus). Nevertheless, as with Germany, December 2022 was Denmark’s worst month for excess deaths in the whole of the eight-year period 2015-2022. Likewise, Norway, which had no excess deaths in 2020, had a disappointing 2022.

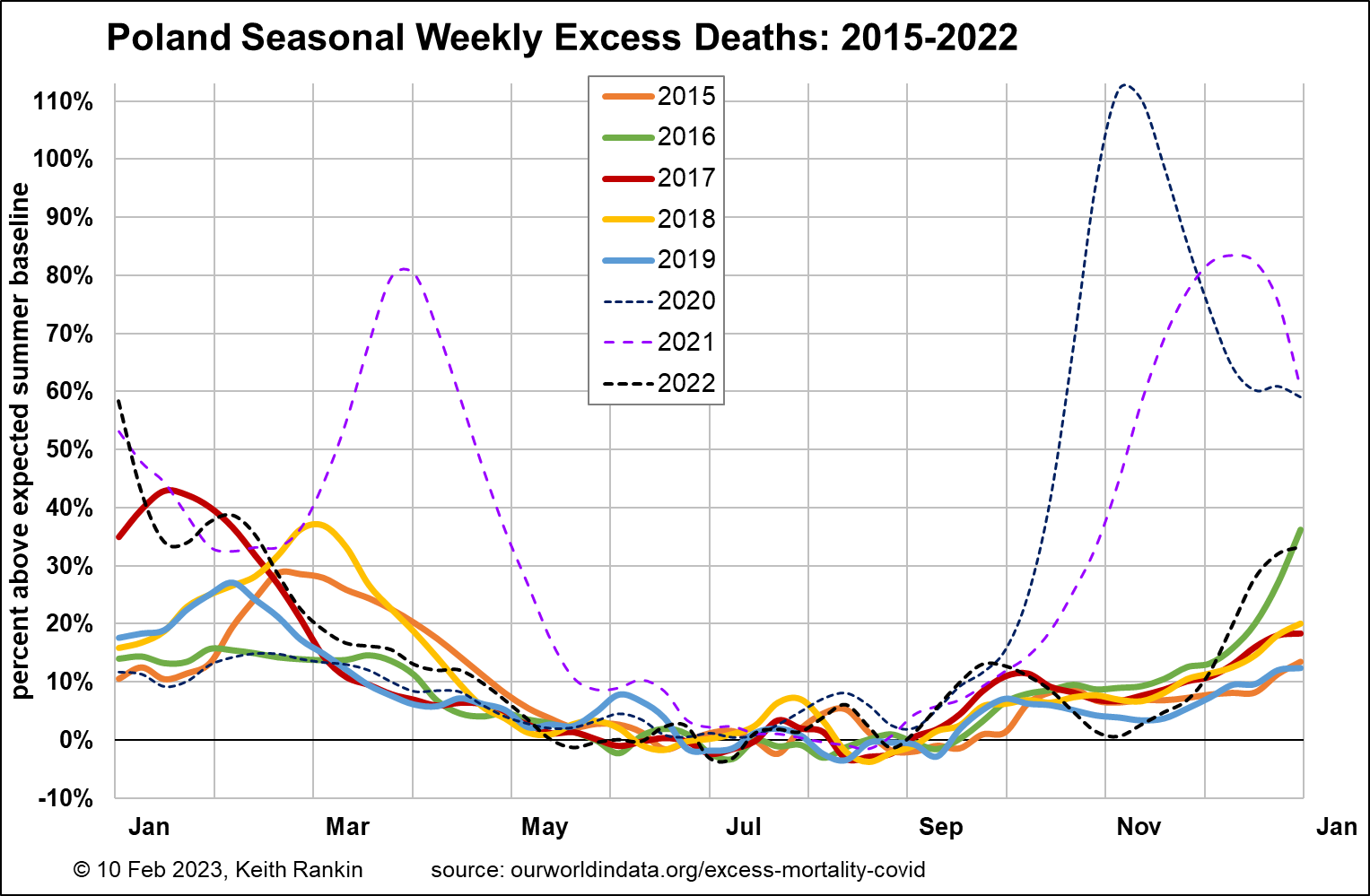

On the other hand, Poland, which had no excess deaths for the first six months of the pandemic, also had a normal epidemic year in 2022. Quite unlike the previously mentioned countries. Instead, Poland had a really bad 15 months, from October 2020 to December 2021. Poland, like most other Eastern European countries, appears to have suffered initially – in late 2020 – from an unusually weak level of general immunity. And then, by 2022, most of the people most vulnerable to Covid19 had already died, mostly in 2021.

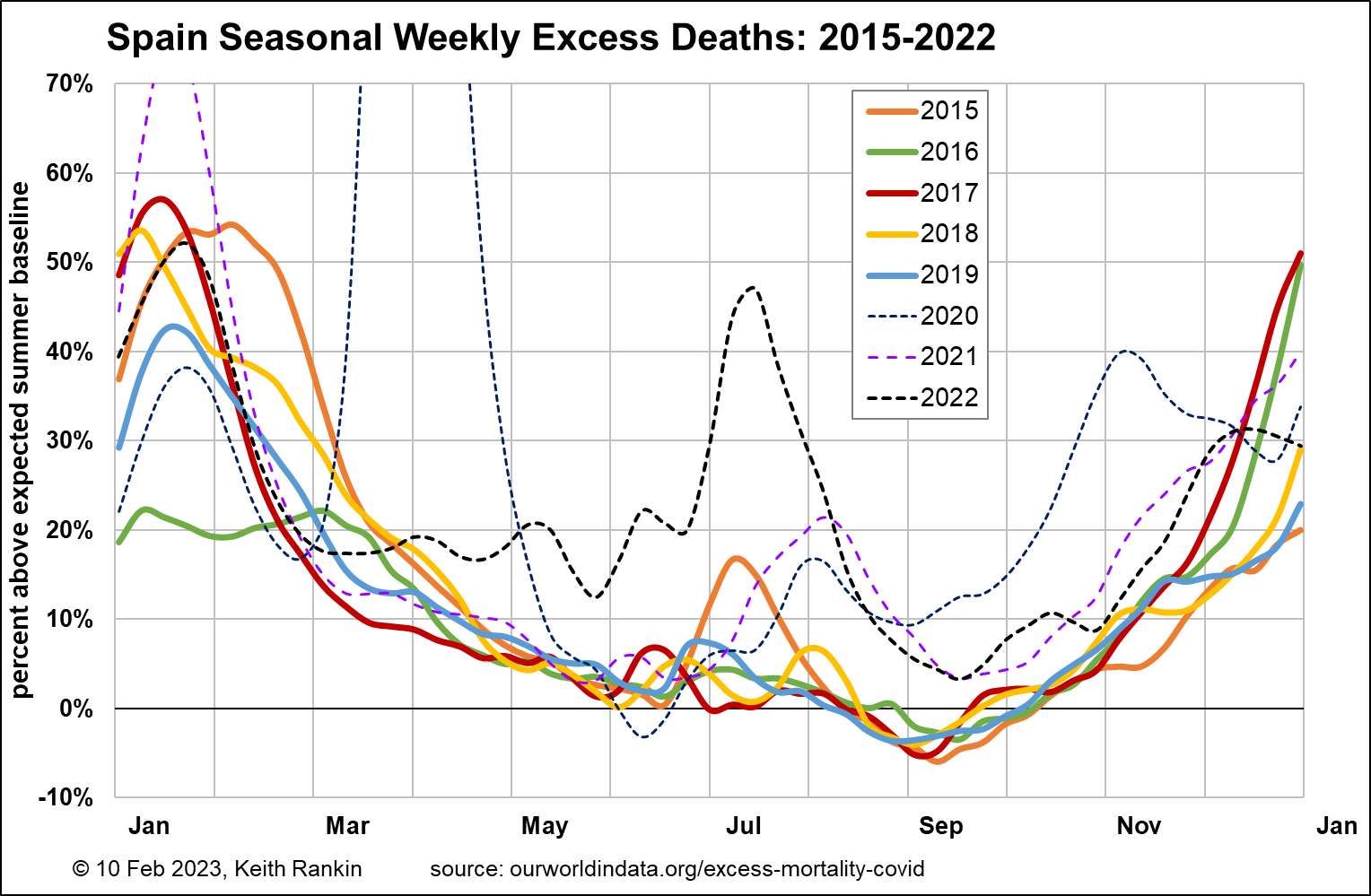

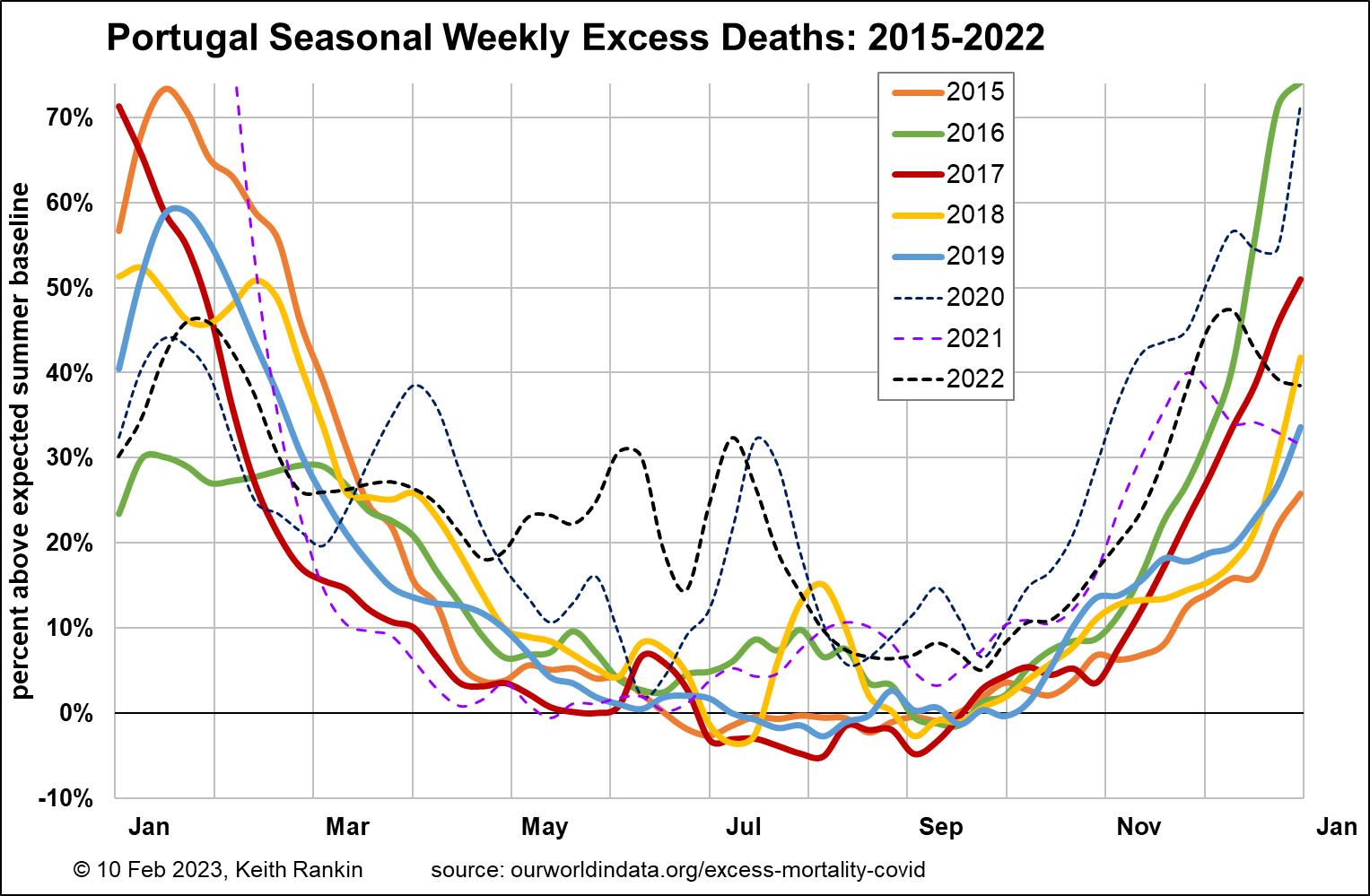

Finally, Spain and Portugal. These two countries were more severely impacted in the first year of the pandemic than any of the previously mentioned countries. Portugal proved to be particularly vulnerable to the alpha variant of the coronavirus, in January 2021. (We also note that, like Austria, Portugal shows more general seasonal variation than its larger neighbour, again simply because it is much smaller than its neighbour.) While Covid19 deaths have conformed with the general pattern of winter deaths in these two countries, summer last year was problematic in the Iberian Peninsula. In mid-2022, the Covid19 problem – linked to tourism – was compounded by likely excess deaths arising from the heatwaves and wildfires.

The lesson for Aotearoa New Zealand is that pandemic-consequent mortality is not over yet. As much as locals prefer not to believe it, New Zealand and New Zealanders are not exceptional. The mortality experience of New Zealand in the southern autumn and early winter of 2022 was not unlike that of Norway in its northern autumn and early winter of 2021. It is quite possible that New Zealand’s experience this coming autumn and winter will be similar to that of Norway in late 2022. New Zealand still has many vulnerable people.

______________

Keith Rankin (keith at rankin dot nz), trained as an economic historian, is a retired lecturer in Economics and Statistics. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand.