Analysis by Keith Rankin.

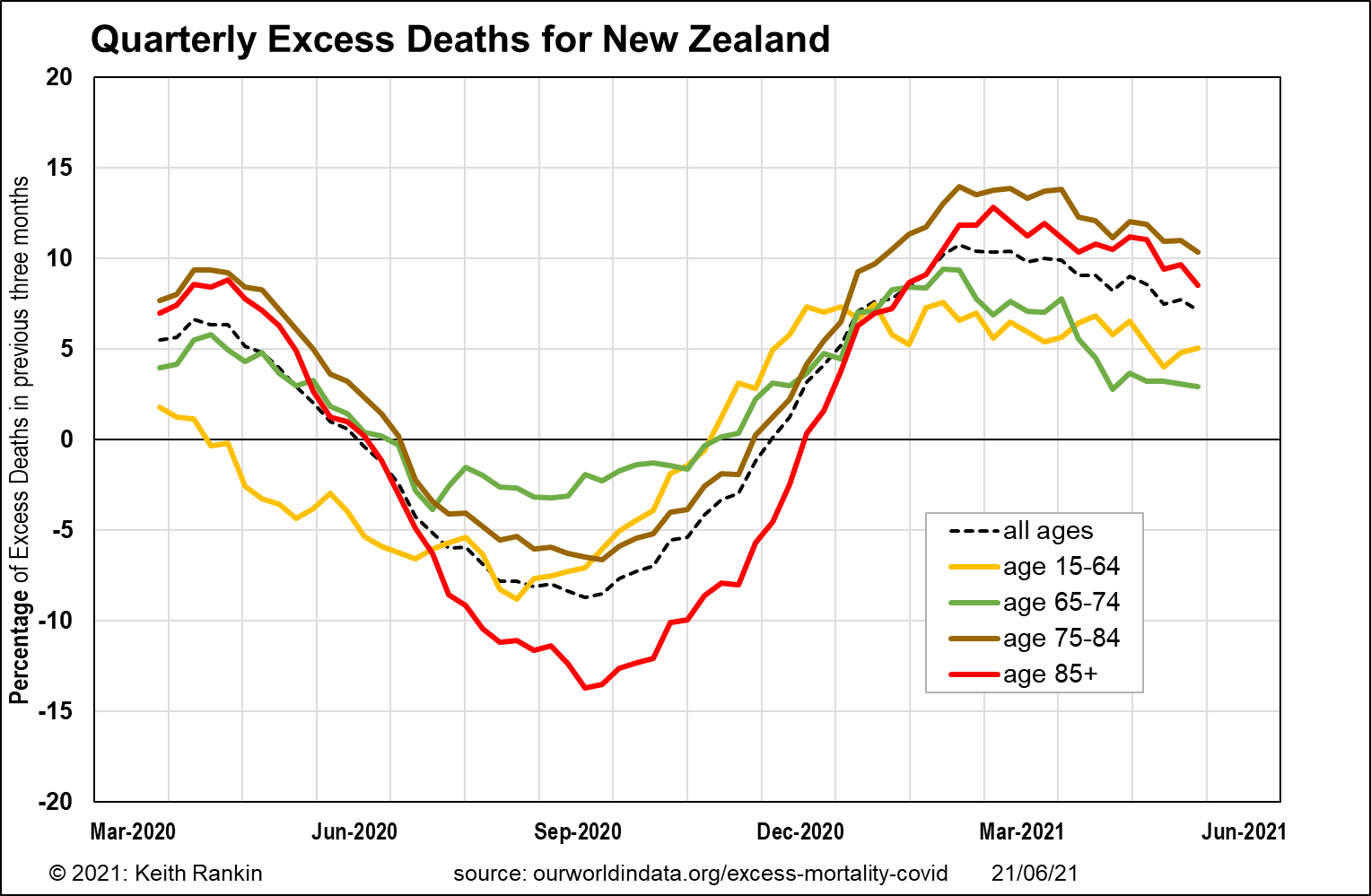

The international source for these data calculates the percentage increase (decrease if negative) of deaths compared to ‘expected deaths’. There is a weakness in the data, in that ‘expected deaths’ is simply the average for 2015 to 2019. Thus, it does not account for rising populations in the various age cohorts. New Zealand has an unusually large ‘baby boom’ cohort, compared to all comparator countries. Also, New Zealand has a bigger ‘young’ cohort than most economically developed countries, meaning that its population is rising relatively quickly. More people means more deaths, but not necessarily higher death rates.

The chart shows quarterly averages, meaning that the most recent data are for the whole of March, April and May 2021.

New Zealand is a potentially good benchmark country, because Covid19 deaths have been too few to register on a chart of excess deaths. Thus, the New Zealand chart shows the impact on mortality of the preventative emergency response to Covid, plus any other underlying reason for increasing or decreasing deaths.

We clearly see that the Covid19 restrictions prevented many deaths, from winter infections, to New Zealand’s oldest residents. Subsequent 2021 data suggests that some deaths were simply postponed by six months. The pattern is similar for 75-84 year-olds, as for older residents.

We see that baby boomers – in green – gained least from the lockdowns. And they appear to be settling at death numbers about four percent above the 2015-19 average; mainly a measure of rising numbers of living people in the boomer age group. The working-age group appear to be settling at higher rates of death than they experienced at pre-covid times. It is likely that this (yellow) death pattern is mainly driven by 45-64 year-olds, who die at greater rates than younger adults. These are ‘Generation Jones’ and ‘Generation X’; the latter is a generation I have been long concerned about.

To understand if we need to be specially concerned, we need to compare with other comparable countries. (See my earlier Covid19 and excess deaths.)

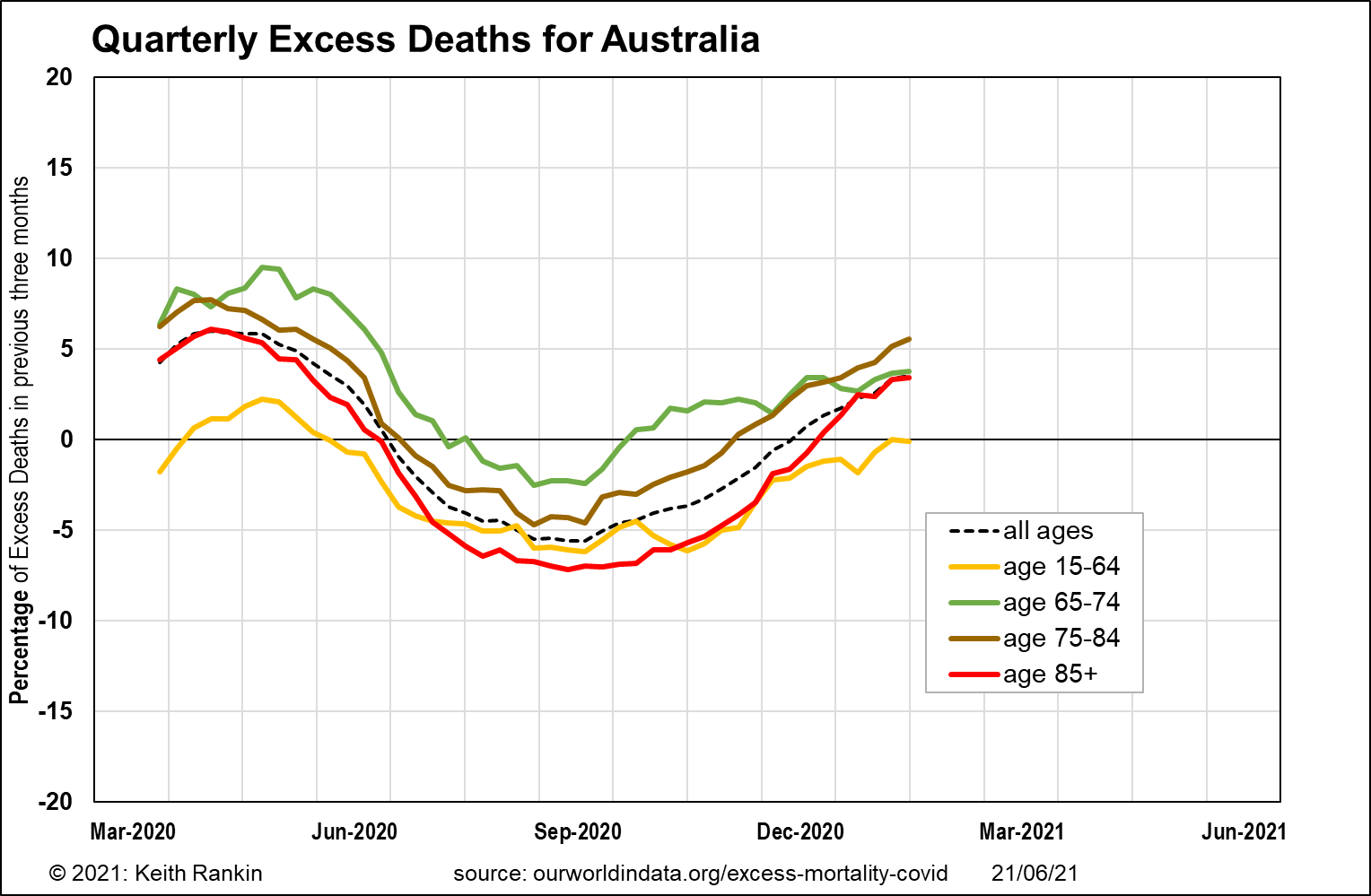

Australia is slower to release its mortality data than most other economically advanced countries. While the pattern is generally similar to that of New Zealand, it looks like Australia has significantly fewer ‘postponed deaths’. There is also a sense that working-age adults are under less stress in their lives than are working-age New Zealanders.

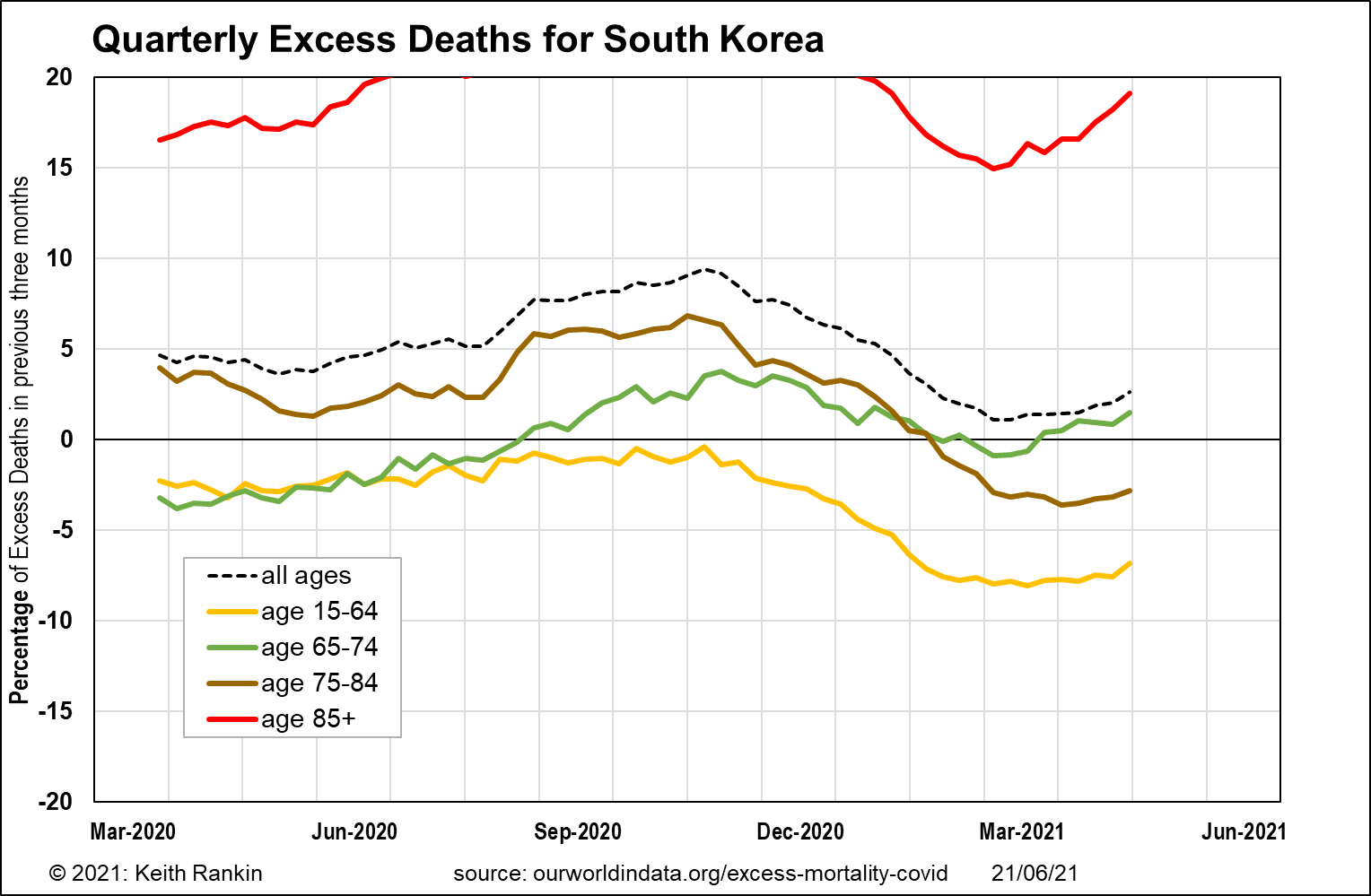

South Korea, lost more of its relatively small population born before 1936. Other age groups, including that raised through the tumultuous years of Japanese occupation and the Korean War, were barely affected (in deaths) by the pandemic, and are showing all the signs of increased longevity for both working-age adults and the generation born during World War 2.

(Note that I have clipped Korea’s Covid19 mortality peak for the very old, in order to keep the value scale the same for each country’s chart.)

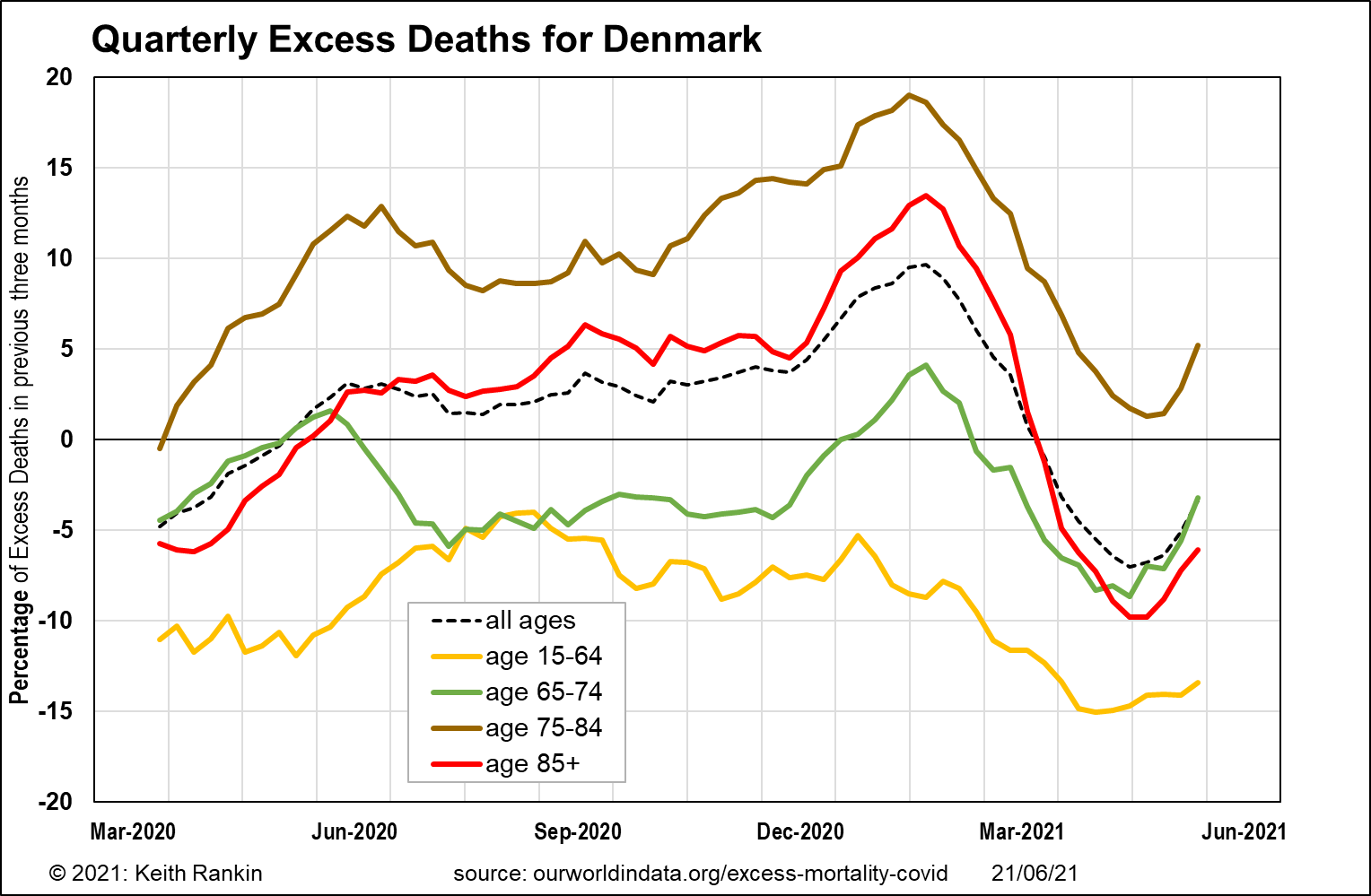

While Denmark is not a country without problems, it is a country that treats its younger people well, and it shows. Denmark is particularly interesting as a European Union country which does not use the Euro. It was the pioneer of negative interest rates (from 2014) and does not have a rental housing market that is anything like as defunct as New Zealand.

Despite major outbreaks of Covid 19 in April and December 2020, all age groups in Denmark in 2021 are doing much better than New Zealand.

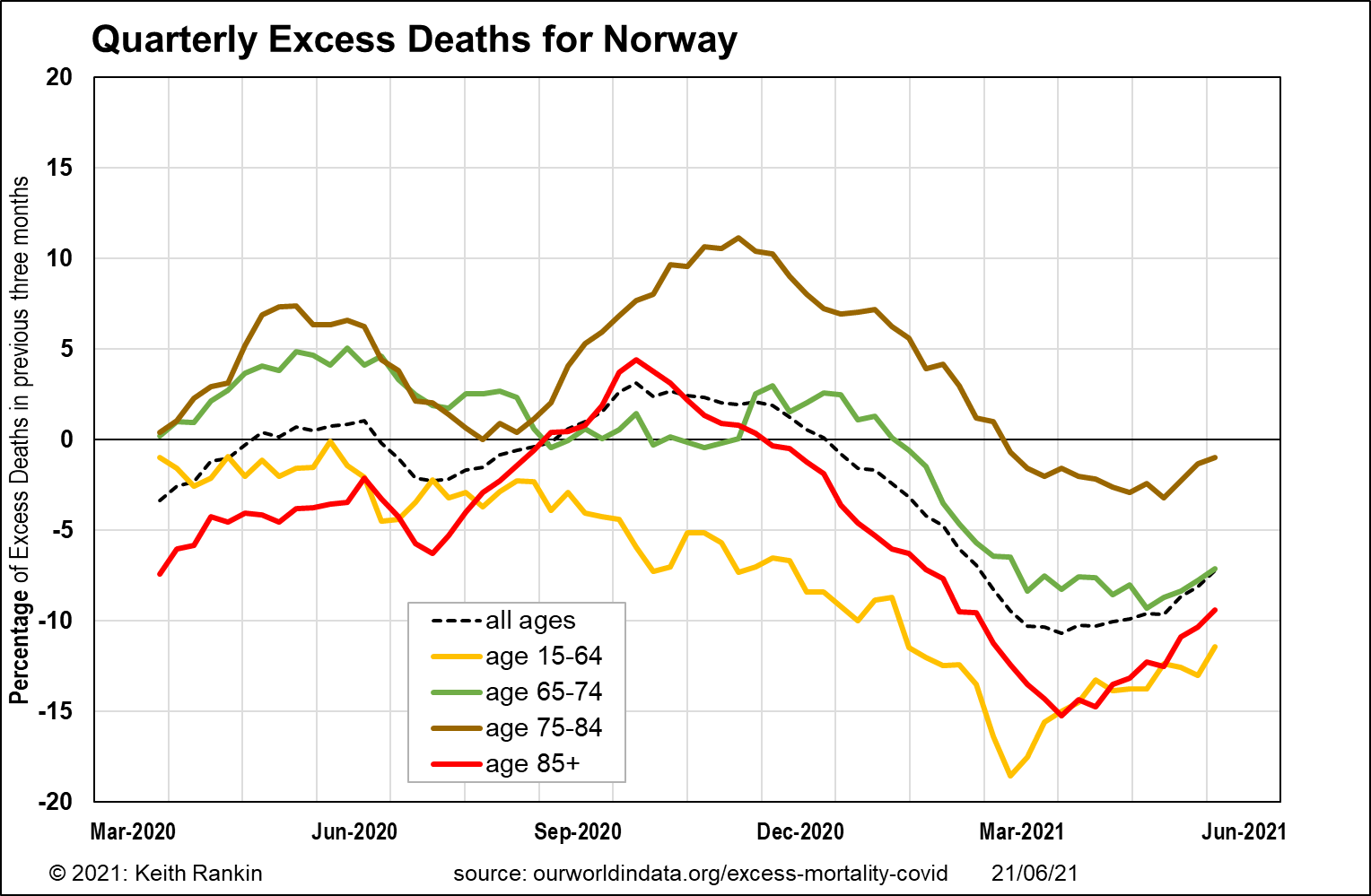

Norway, like Denmark and New Zealand, has a population of between five and six million people. Covid19 mainly impacted on 75-84 year-olds. All age groups are doing much better than New Zealand, and it’s not clear that Norway would have an age structure substantially different to New Zealand.

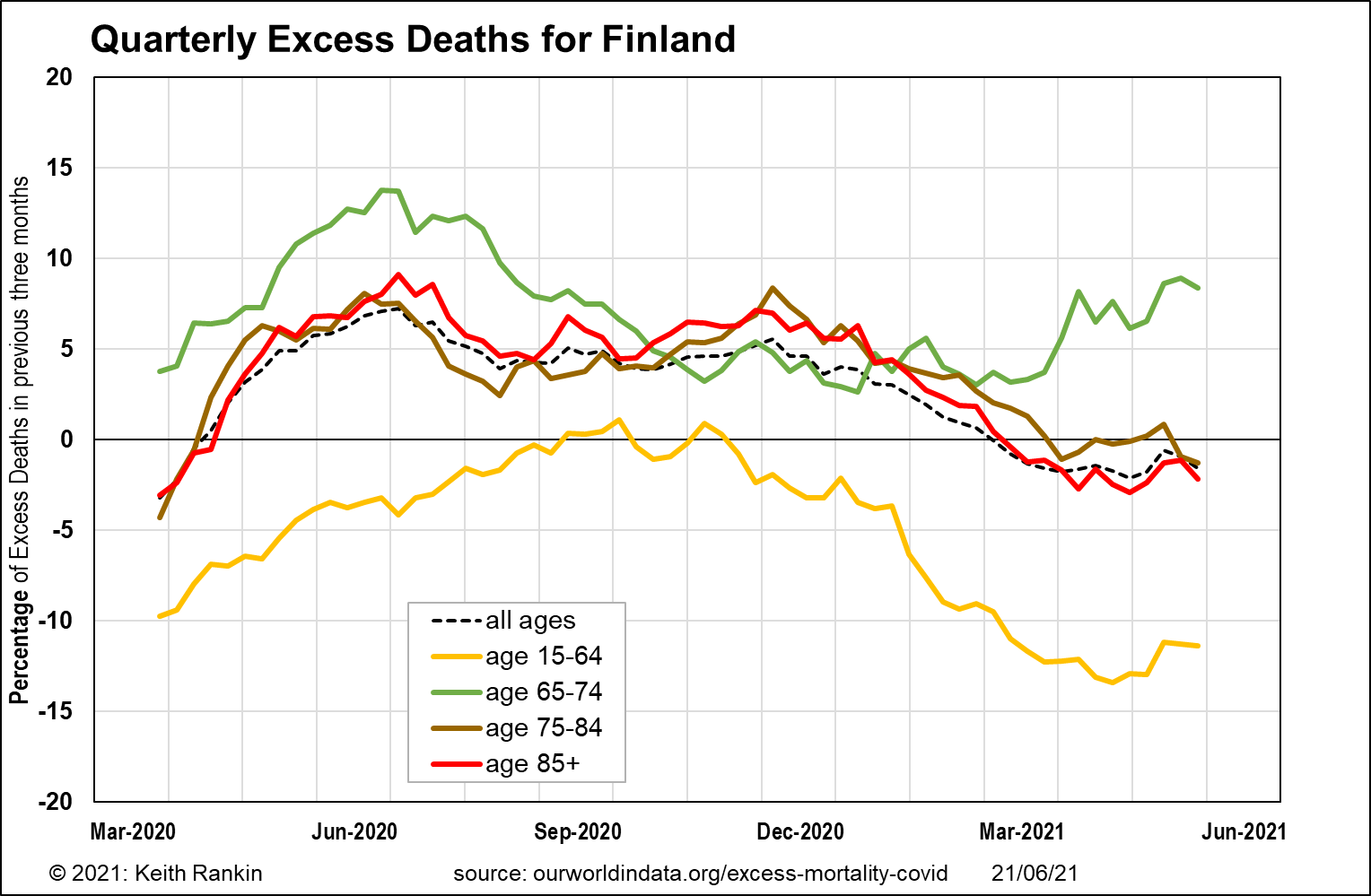

Finland was the Nordic country least affected by Covid19. (And it is another country with just over five million people.) Younger people were hardly affected at all, though there were some deaths that offset what would otherwise have been a fall in death rates, in the northern summer and autumn.

Of interest to us in New Zealand though, is that the baby boom generation (aged 65-74) did not fare well in Finland. Unlike Finland’s small Nordic neighbours, Finland is one of several countries – others include Spain, Greece, USA, Poland – for which excess deaths of 65-74 year-olds are markedly higher than for 75-84 year-olds. This may indicate that working lives in Finland may have included higher levels of social stress than in their Nordic neighbours. Indeed, this may reflect that Finland is the only Nordic country in the Eurozone of the European Union, and that Finland (like Greece and other southern Euro countries) has been subject to degrees of fiscal discipline that emanate from Brussels and Berlin rather than from Helsinki. All may not be well in this allegedly happy country.

These six countries have all dealt with the Covid19 pandemic successfully so far; New Zealand and Australia by literally shutting it out, and the others by striking successful balances made possible by having less stressed societies.