Keith Rankin, 26 February 2019

Until late 2018, New Zealand’s immigration statistics have been woefully inadequate. While it has always been possible to keep taps on the total number of people in the country – through births, deaths, and net international passenger movements – ‘official’ net immigration numbers have long been calculated by stated intentions (as on arrival and departure cards) rather than by actual outcomes.

For statistical purposes, immigrants are people who arrive in New Zealand, and stay for at least 12 months without leaving the country.

For recent history, actual outcomes have been ascertained by matching arrivals and departures (through passports, not self-declared passenger data). For 2018 new arrivals, the numbers of people expected to stay in New Zealand for more than a year have been estimated using information associated with their visa. For 2018 recurrent arrivals, their likelihood of staying at least 12 months is estimated from a travel history of at least 16‑months.

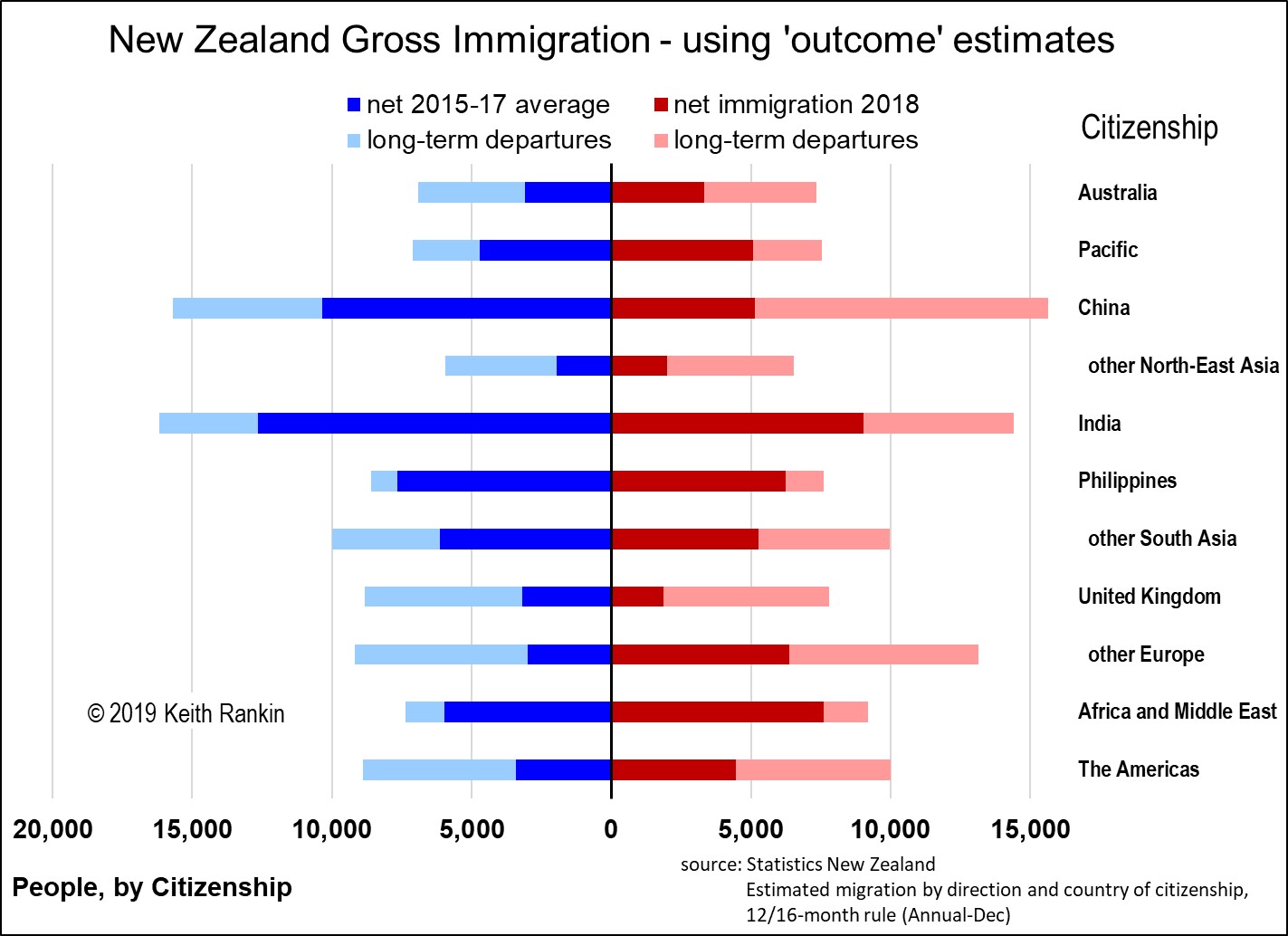

Immigration statistics have been recalculated from 2015, using this new method. The chart shows 2015‑17 annual average long‑term arrivals (total blue), 2015‑17 annual average long‑term departures (light blue), with annual average 2015‑17 net migration in dark blue.

The equivalent 2018 data is shown in red.

The data in the chart is categorised by nationality (country of citizenship), and excludes New Zealand citizens. (For New Zealand citizens net immigration is negative. This is partly because some immigrants acquire New Zealand citizenship, and later depart as New Zealand citizens. It is also because New Zealand has always been a country of emigration as well as a country of immigration.)

The most important feature of the chart is that, while gross immigration has changed little (though with increases from Europe, the Americas, and Africa), departures of immigrants have increased markedly. The result is a significant overall fall in the net immigration of foreign citizens.

The places with the least return migration are Philippines, Pacific countries, and Africa (especially South Africa). These are the most obvious cases of economic migration, where immigrants are largely content with life in New Zealand. These are also the countries from which most immigrants seek New Zealand citizenship; so when they leave they are more likely to leave as New Zealand citizens.

In the middle are countries with high numbers of international students – China, India, South (including Southeast) Asia – reflecting the ambivalent immigration status of international students. These are also countries whose middle-class residents have aspired to hold alternative national residencies while never quite leaving their countries of origin. Tellingly, however, China is showing substantially more return migration than previously. It is coming to look more like the richer countries of Asia (North-East Asia) and the English‑speaking developed countries, with the highest levels of return migration.

For these economically‑advanced countries, a major driver of return migration will be dissatisfaction – much of that due to inflated initial expectations of life in New Zealand. There will also be a considerable amount of churn associated with a rich anglo middle‑class who see themselves more as citizens of the world than as citizens of a particular country. These are heavily globalised people, for whom traditional concepts of international migration do not apply. Their migration patterns are driven as much by the ever‑cheaper price of air travel, facilitating a transience (eg home‑ownership in multiple countries) and consumerism that imposes a high environmental footprint on the world.

Finally, there is an increasing category of lifestyle refugees – suggested from European and American data. These are people – mainly social liberals – driven by fears of environmental disaster and of political populism; and probably in part unspoken concerns about how immigration in their home countries has changed many of their cities. Europe (excluding the United Kingdom) has bucked the overall trend, showing easily the biggest increase in net immigration. This is especially true of Germany and France, which showed a near‑doubling of gross immigration in 2018. Time will tell whether these people stay.

It is great to see Statistics New Zealand finally creating some worthwhile immigration statistics; statistics that show high levels of migrant departure as well as of arrivals. What we need also is reliable information about internal migration – changes in the distribution of population within New Zealand. My sense is that Auckland has experienced a disproportionately large amount of departures, to other parts of New Zealand and other parts of the world. Many people have cashed up their capital gains in residential property.