Analysis by Keith Rankin.

Are wars affordable? The answer of course is ‘yes and no’.

Affording a war is different from financing a war. To make any new thing affordable, either there must be a reallocation of resources or a deployment of resources not otherwise in use. Or a mix of both. Further, resources get destroyed, and not only the resources of the ‘loser’.

Wars may be fully tax-funded – that is, by increased taxation – by one or more belligerents; but most usually they are not. Otherwise, wars are financed. Financing is a mechanism which enables the distribution of spending to differ from the distribution of income. Typically, spending by warring parties exceeds their incomes, so must be financed through government ‘fiscal’ deficits.

Income is the rights to current goods and services; that is, to current output. Present tense. In particular wages, profits, rents, royalties. Finance is the principal mechanism whereby such rights to current output are transferred by some people (including businesses and governments) to other people. By giving up a right to current output, a party either gains a right (ie a ‘claim’) to future output or is fulfilling an obligation – a debt – incurred in the past. Thus, giving up rights to current output is called either ‘saving’ or ‘debt repayment’. Saving, conceding such rights in return for claims on future output, is commonly understood as lending or ‘advancing’ funds.

We note that in many cases, debtors – parties holding obligations incurred in the past – have discretion over when they fulfil their obligations. Likewise, savers (creditors) have some discretion over when they call in (ie realise, spend) their savings; that is, discretion over when they exercise – ie liquidate – their historical claims to current output. As a general matter, is it a good thing if those two matters of debtor and creditor discretion balance out, creating a sense of ‘equilibrium’.

Historically, however, creditors have often failed to liquidate their claims at all; many creditors like to hold onto their claims for indefinite periods, thereby enabling debts to be merely ‘serviced’ rather than repaid. Unrealised claims are called ‘wealth’, and many people like to hold wealth until they die, rather than spend it.

If insufficient current output is purchased by past savers, it becomes a systemic requirement that new debts are contracted and spent.

When sovereign governments contract new debts to fulfil this systemic requirement (possibly as ‘debtors of last resort’), this is ‘fiscal accommodation’. When governments refuse to contract new debts to fulfil this systemic requirement, we may call this either ‘fiscal consolidation’ or ‘public austerity’.

Wars – and preparations for war – may be destructive (or at least non-productive) examples of fiscal accommodation; such accommodating militarisation may achieve that purpose without specific intent to do so. (In the 1930s the renowned economist John Maynard Keynes offered, as an example of contextually beneficial non-productive fiscal accommodation, governments paying workers to dig up holes and fill them in again!)

Wars

Medieval wars were often short-term affairs, because of seasonal patterns of labour demand. Wars have for the most part been labour intensive; and that’s still the case today, even if the casualties of post-modern wars are more likely to be civilians and less likely to be soldiers and sailors.

Medieval sieges often had to be terminated around August because the soldiers in the sieging army had to return to collect the harvest. September was the time of the year when there was virtually zero unemployment. Siege defence was made possible because harvest labour requirements would likely break the stalemate. The corollary is that medieval wars could be afforded because, in late-spring and early-summer, there was seasonally unemployed labour.

In the modern period (approximately 1490 to 1990), especially in Europe, labour became increasingly divorced from agriculture, making it possible to have ever larger standing armies (and navies), making bigger and longer wars possible. Further, the modern period saw the emergence of sovereign nation states; so, increasingly, war finance became intrinsically connected to public finance. Wars of exploitation and territorial expansion became a central feature of the emergent mercantile States.

Public finance and war finance were essentially the same thing in the golden eras of merchant capitalism (roughly 1550 to 1800) and subsequent industrial capitalism. That financial conflation is re-emerging as a new reality of the twentyfirst century, as sovereigns (and their foreign state and non-state proxies) up their military spending while simultaneously diminishing their commitments to the peacetime provision of public goods.

Fast forward to the years from 1989 to 2011

This transition period from modern to post-modern may be seen as a particularly peaceful period – after the Great World War of 1914 to 1945; after the wars of recolonisation and decolonisation which may be seen to have ended in 1979 with the revolution in Iran and Vietnam ending the post-colonial genocide in Cambodia; after the wars in Lebanon, the Falkland Islands, and Iran-Iraq; and after the fall of the empire of the Soviet Union.

The millennial years 1989 to 2011 are sometimes called the ‘unipolar moment’, when the United States could and would call the shots; typically with a foolhardy and exceptionalist perspective of the world as a kind of playpen for Washington and New York largesse. And with a neoliberal outlook through which narratives about the Great Depression and World War Two were recast. In the latter case, World War Two became a grand narration of ‘Hitler versus the Jews’; most of the many other lessons arising from the years 1914 to 1945 were largely forgotten.

I am particularly interested in the affording and financing of the Second Gulf War (essentially 2003 to 2009, an asymmetric war between United States and Iraq); although good starting points are the post-Tiananmen (after 1989) emergence of China and the execution in 1990 by the United States of the First Gulf War.

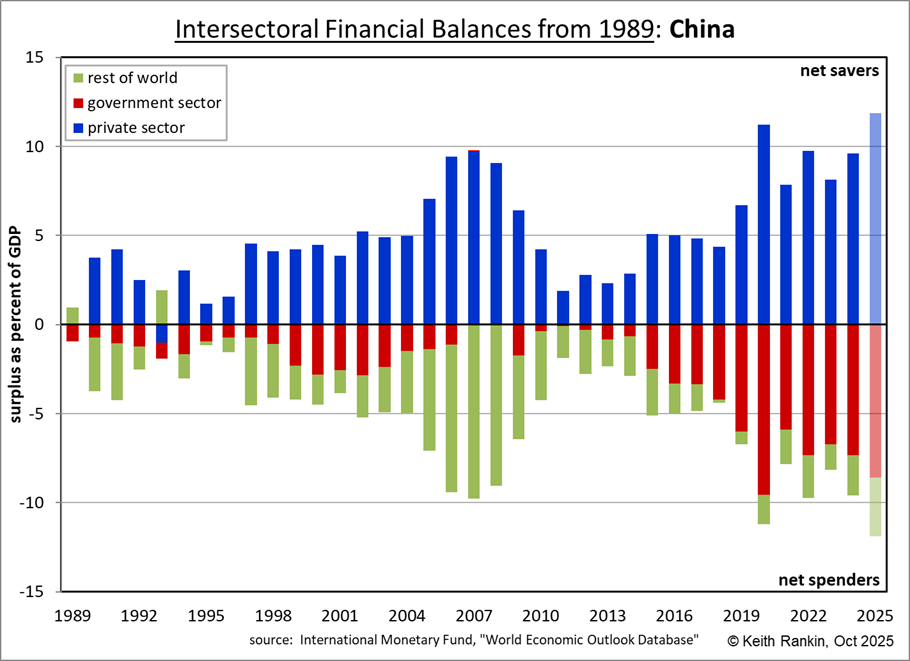

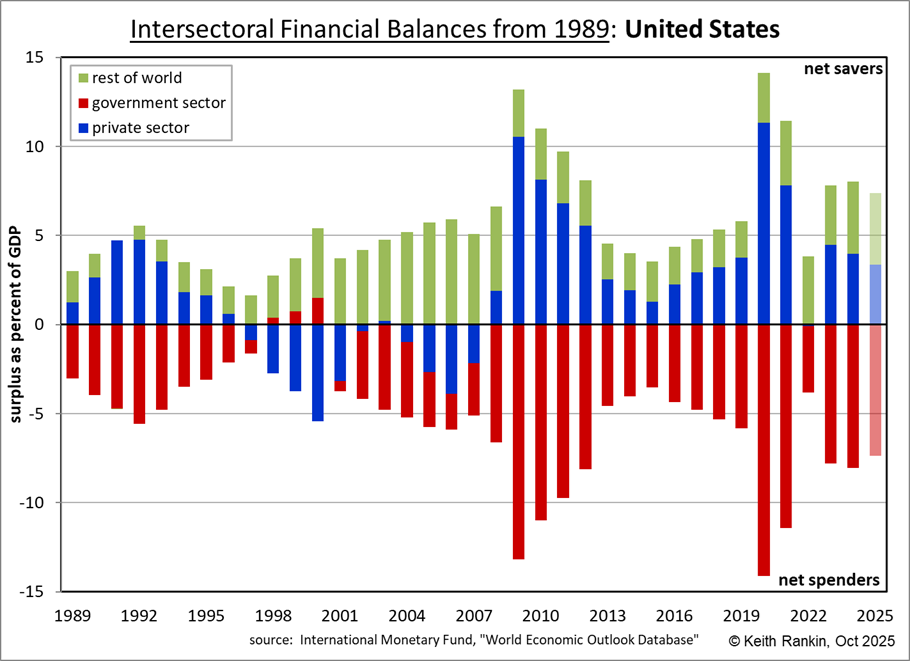

These charts of financial balances for China and the United States give some important clues about who paid for the Gulf Wars. (For the United States in particular, it is necessary for now, to not be distracted by the dramatic financial accommodations between 2009 and 2021, relating to the Global Financial Crisis and the Covid19 Pandemic.) They show variations over time in private saving and spending, government deficit spending, and these nations’ saver/spender relationships with their outside worlds.

We note that most of the economic and financial cost of war comes after the main event (eg after 1990, and after 2003); as military equipment needs to be replenished, armies need to be expanded, and destruction zones need to be rebuilt. Indeed, the costs of a standing defence force are high whether or not there is a war.

1990, the middle of a period of both economic and financial flux in the world, came at the end of a recovery in the United States following the 1987 sharemarket crash. So, almost unusually, there was no speculative bubble in place, there was increased saving as people looked more to future spending than present spending, and the labour market remained weak.

For the United States, we see in the years from 1991 to 1993, high saving in the private sector – largely household saving – and comparably high spending in the government sector. Thus, domestic private savings directly funded the war. Unemployment in the United States was lower than it otherwise would have been. While savers were not asked whether they were happy that their caution was being translated into government military spending, it’s unlikely that they minded too much; the ‘war against Saddam’ was not an unpopular war in the United States.

In times of recession, when more people than usual are unemployed or underemployed, affording a war is easier but financing a war is harder. Liberal governments must make financial accommodations by departing from the standard fiscal rules they impose upon themselves. (We note that, just this year, 2025, the German Bundestag has made such an accommodation, and abandoned its self-set and dearly-held fiscal rule; giving itself a blank cheque to pursue debt-funded military spending.)

Most modern wars have been afforded through a process of restrained consumption, financed through the mechanism of new government debt and a build-up of household credits; governments owing, and households owning new debt. As a side-effect, and considering the United States, this affording and funding enlarges the combined balance sheet of American banks: more assets (government debts) and more liabilities (private savings).

Affording wars is always a matter of economic resources being deployed into military theatres, whether that is redeployed from civilian production or a reduction of resource underemployment. From a financing point of view, the four options are that wars are funded by taxes (which would not show up on this type of chart), by domestic saving (as happened in the United States from 1991 to 1993), by foreign saving (as happened in the mid-2000s), or by foreign aid from patron to proxy.

War financed by foreign saving may mean direct or indirect foreign funding. Much of the Allies funding in the Great World War was financed by American debt which, in the fullness of time, would be written off; making that war significantly American gift funded, even if at the time the advances were only intended and consented as loans. Nevertheless, the United Kingdom afforded their war only with substantial reductions in normal consumption; this was even more true for most of the other participating nation states.

In the United States chart above, we see (in green) that in every year shown except 1991, the United States has incurred debts to the rest of the world. Though these foreign advances were unusually low in the early 1990s. America’s war in 1990 was domestically funded, and relatively easily afforded.

(We note that that Gulf War involved both an invasion by Iraq and an invasion of Iraq. I make no attempt to discuss the affording or financing of the war from the point of view of either Iraq or Kuwait. Clearly, however, there was a substantial loss and degradation of life in Iraq, and degradation of land and infrastructure.)

The Wars of the 2000s, especially the Second Gulf War from 2003

The United States economy changed dramatically with the birth of the Internet-Age, just after the First Gulf War. Private balances follow a classic ‘bubble’ formation from 1994 to 2000/01; this came to be known as the dotcom bubble, and was characterised by a new ‘information technology’ sector being speculatively debt-financed. Government tax revenues ballooned, leading to unheard-of government budget surpluses. In addition, the United States economy attracted increased foreign credits before the turn of the millennium, though not much then from China.

We can see the collapse of the dotcom bubble in 2001, with a marked reduction in private debt spending, and the ensuing unusually high foreign financing of the United States economy.

The wars of the new-millennium began with the United States’ invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, followed by the bigger United States invasion of Iraq in 2003. These wars were foreign-funded, the US chart shows, and lasted – in their predominant phase – throughout the Bush presidency. (Refer Iraq War troop surge of 2007.)

We can trace this funding of the Bush-wars by examining the China chart. From 2002, we see a clear rise in Chinese private saving and of ‘foreign investment’. The ‘rest of the world’ percentages represent spending in the rest of the world (from China’s perspective) made possible by non-spending in China.

At its peak, China’s foreign investment ‘current account surplus’ – for our purpose, China’s excess of exports over imports – reached almost 10% of GDP in 2007. This co-dependency of Chinese exports and American imports has been called by some Chimerica; the best known proponent of this concept is the British global historian Niall Ferguson.

As well as considering the percentages, we remind ourselves that Chinese supercharged annual economic growth, which bottomed-out at 8% in 1999-2001, climbed to 14% in 2007. Given earlier growth in the 1980s and 1990s, China was no longer starting from a low base. These were massively increased levels of Chinese economic output in the 2000s; output sent from China rather than spent in China.

The result was that industrial capacity within the United States was freed up to supply military goods rather than civilian goods. While China provided the ‘butter’ (ie consumer goods), Uncle Sam was freed to specialise in the production and deployment of ‘guns’.

While China paid for the Second Gulf War through its massive export surpluses, for the West in general and the United States in particular, the war was fought for free; a ‘free lunch’ so to speak. Of course it wasn’t technically free; China built up a massive amount of financial claims on the United States, though it was never clear how or when China might exercise those claims. China is yet to show any desire to acquire the American imports which would constitute the settlement of China’s claims on the United States.

China will only be reimbursed for its massive lending to the United States in 2003 to 2008 when we see, in its future financial balances’ chart, a whole lot of green on the upper ‘savers’ side. Otherwise, China’s loans to the United States will morph into gifts. An export surplus can only be reimbursed in the form of an export deficit; not China’s style in current or near-future times.

Tax Cuts

Not only did the United States wage two major wars in West Asia, close to America’s Indian Ocean antipodes, it did the unheard-of for a nation at war; it reduced its tax rates. While the most obvious way to fund a war is to raise taxes, the United States did the precise opposite; to not fund the wars ‘because it could’. China was happily paying for those American wars. For many Americans not directly involved, these wars were more than a ‘free lunch’; they were, through tax cuts, a ‘sugar hit’.

Indeed, this detachment of fighting from cost-bearing has become the most dangerous facet of the emergent ‘Warrior epoch’. Western elites have come to believe that they can undertake wars – be they ‘good wars’ or ‘bad wars’ – without themselves facing up to the reality that all wars are costly.

The United States legislated two major rounds of tax cuts, in 2001 and 2003. The first round was undertaken in the light of the Clinton budget surpluses (see the year 2000), and without awareness that war was coming. Those Clinton fiscal surpluses were unsustainable, a consequence of the dotcom bubble mini-boom, though the tax cuts (ill-targeted as they were) helped to fiscally accommodate the recovery from the 2000/01 dotcom bust.

The 2003 federal tax cuts were inexcusable. Initiated just as the pre-Gulf-War hype was peaking, these tax cuts passed through Congress and the Senate during the peak initial phases of the war. The incongruence of simultaneous military aggression at scale and tax decreases was astounding in its brazenness.

After 2011

The principal wars in the 2010s were located in Afghanistan and Syria; there was additional militarisation in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, associated with the eastward expansion of Nato.

China played a constructive new role in that decade.

An important feature of global financial imbalances – very clear in the American chart – was the Global Financial Crisis, showing resurgent American private saving (mainly debt repayment) and the spectacular (and necessary) US Government accommodation of that dramatic change in private behaviour. Then we see a return to normality from 2013 to 2019. Higher than usual United States government deficits were a critical part of the global recovery from the financial crisis. (We may mention in passing that the New Zealand government’s fiscal policy – under National and Labour – has been and still is non-accommodating; the pandemic year 2020 being the exception that ‘proves’ the rule.)

For the second critical component of the 2010s’ global economic recovery, we can see a big change in China’s financial balances. In particular, we see the emergence of the Chinese consumer and taxpayer (much less blue and less red). And Chinese net exports substantially diminished as a share of the Chinese economy. Consumer spending and government spending in China and the other BRICsrevived global demand for non-military goods and services.

Although the United States incurred a specific debt to China during the Second Gulf War in the 2000s, subsequently the whole West ‘owes’ China a considerable debt of gratitude for its role in restarting the global economy around 2010. Thankyous to China have been considerably lacking, however, as the West increasingly seeks to point its military hardware at China.

The West – led by the United States – has gamified war, and has become indifferent to non-western lives. There are also too many signs that western elites are becoming indifferent to western working-class lives; starting with indifference to the many immigrants who are already performing so much of the necessary labour to support higher-middle-class living standards.

China, already on the verge of a balance-sheet recession in the view of Richard Koo, may now be following in the financial and economic footsteps of Japan in the 1990s (see my Red Gold; Japan’s lesson for the world). Certainly China’s financial balances’ chart (above) is starting to look very Japanese, with a smallish and stable export surplus, and large government deficits.

2020s’ Wars

After the 2020 Covid19 Financial Crisis, which, as in 2009, required huge fiscal accommodations – especially by the United States federal government – wars have become proxy affairs whereby the means of war have been largely gifted by patrons to their proxies. Such financing leaves only small marks on countries’ financial balances charts. Though the patron nations will have larger-than-otherwise government deficits; see the United States’ government balance (above) for 2023 and 2025 (and the 2025 forecast).

The financing of the two sides of the Sudan ‘Civil War’ appears too convoluted to examine here. It would seem to involve proxies of proxies, and to be an important outlet for internationally traded military goods.

For the West, the affording of the wars in Ukraine and Israel-Palestine would appear to be mainly through a mix of gifts and loans by patron governments, meaning involved governments undersupplying too few peacetime public goods. (Too little ‘butter’, to use that metaphor, and too many guns.)

Russian citizens will be incurring substantial opportunity costs, mainly through higher taxes, a reallocation of government spending, and reduced opportunities for its citizens to live international lives. Ukraine seems to be funding its war through a mix of foreign gifting and government debt; though its people – like Russians – have been paying a high price through reductions in their living standards.

Israel continues to be a net exporter, so its deliveries of military hardware from the United States should definitely be regarded as aid rather than imports. Lucky Israel! To be able to fight its neighbours on such favourable terms is a privilege rarely granted.

In Retrospect

Wars are costly. Very intensive and extensive in the use of resources and the destruction of resources; let alone the loss of quantity and quality of life.

In all wars, all parties incur costs; significant costs. Sometimes, a party to a war can avoid most of those costs through having someone else pay. Of course, the United States paid to some extent for the wars against Iraq in terms of American lives lost and degraded; little cost was borne by those Americans who propagated those wars, though.

The material costs of the wars in the 2000s were paid – indirectly – by Chinese households not consuming large swathes of the goods they produced; Chinese workers and capitalists were, on an increasingly massive scale, exporting the fruits of their labour and their capital to the United States. More sending than spending. Much more. (A Marxian analysis would attribute the seemingly costless affording of the US-Iraq war to the extraction of ‘surplus value’ from the Chinese working class by the American capitalist class.)

Yet these Chinese costpayers didn’t much mind, because – while their abilities to enjoy the increasing fruits of their labours were highly constrained by China’s export policy – they were happily stacking up claims on future production; deferred enjoyment, rather than the pure exploitation which occurred in the early years of Chinese Communism.

China bore the West’s costs in other ways too; in those years Chinese people suffered huge environmental costs, at a time when natural environments were improving in the deindustrialising West.

There was a wider set of ongoing costs, however, arising from the ensuing highly unbalanced global capitalism. United States’ industrial survival is now largely dependent on its specialisation in military hardware and software; meaning that the United States’ economic deformation has made that country into a predatory warrior state. Violences, especially upon non-Americans, are today directly committed by the American state; and through both exported and gifted military goods and services, and through violations committed directly by America’s proxies (and, as in Sudan, by its proxies’ proxies).

Wars, when they happen, are affordable because they happened. They are very costly, both in terms of their opportunity costs (the loss of other uses to which the deployed resources could have been put) and the human misery of death, destruction of habitat and taonga, and injury. They are commonly financed by third parties – eg Chinese households – who may or may not enjoy reimbursement for their credit advanced.

*******

Keith Rankin (keith at rankin dot nz), trained as an economic historian, is a retired lecturer in Economics and Statistics. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand.