Analysis by Keith Rankin.

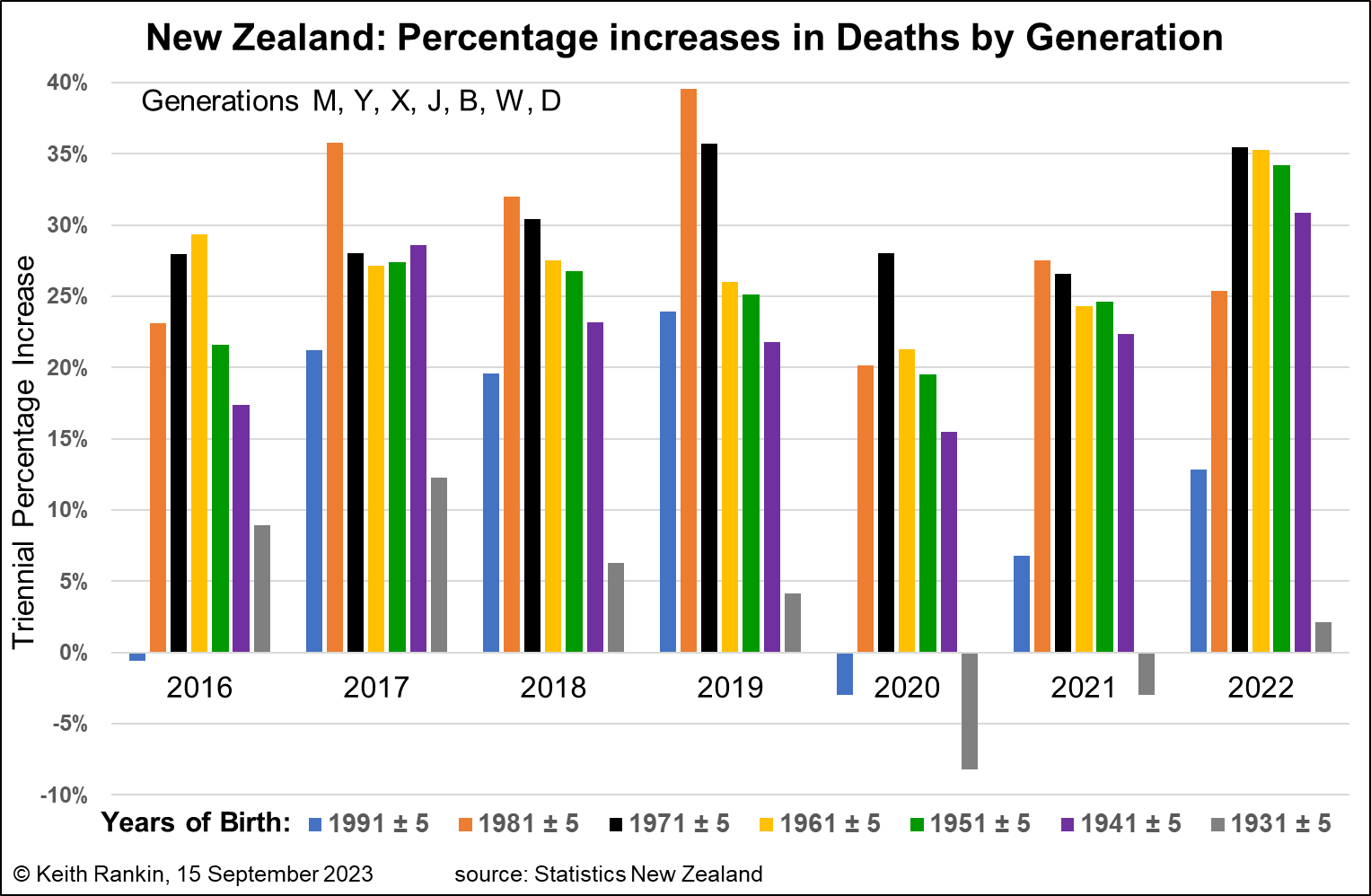

The chart above looks at the changing numbers of deaths for New Zealand’s seven adult generations. The numbers are ‘triennial’ – three-year percentage increases. For example, in 2020, twenty percent (20%) more Generation-Y people died than three years earlier; with ‘three years earlier defined as the average for years 2015 to 2019, and ‘Generation-Y’ is defined as people born from 1976 to 1986.

Deaths in a given year increase because of the aging process, because of population increases for that age cohort, or because of adverse health outcomes (eg epidemics) particular to the years concerned.

We may consider 2016 a baseline of sorts, though each year has its quirks. 2016 was a year of low death rates in Aotearoa New Zealand.

In 2016, there was a small fall in Gen-M deaths (‘millennials’.) But deaths rose in the next three years. The main driving factor here will be net immigration, with there being a significant outflow of New Zealanders in their 20s. From 2017, the impact of New Zealanders returning from overseas will have been important. Also, we note that Gen-M (shown in blue) probably had less of the risky behaviours (compared with older generations) typically associated with males in their early twenties. We also note that for Gen-M, death numbers are very low, so random fluctuation will be present.

In the 2020s, Gen-M deaths fell, and then increased more slowly than other generations. Net migration will have played a large part here, as well as the Covid19 public health measures keeping people at home more.

Gen-Y (shown in orange) and Gen-X have substantial increases in mortality in the years at the end of the last decade. Net immigration will be the major reason; noting that net immigration probably peaks for people aged in their thirties. We should note that 2017 was the year that the global influenza epidemic struck New Zealand, affecting people of all age groups with pre-existing conditions of poor health.

Gen-X (shown in black) is of particular concern, because it shows substantial increases in death numbers throughout the period, even in 2020. For people born from 1966 to 1976, while death numbers are still low, they are not insubstantial. There was a marked increase in Gen-X deaths in New Zealand’s ‘year of covid’, 2022, despite high death numbers already registered in 2020 and 2021.

Generation Jones (Gen-J, shown in yellow) is the generation which most reflects the very high birth rates in the early 1960s. Boosted by immigration – but not as much as generations X and Y – death increases have been consistent for this generation, boosted in the final year by a mix of Covid19 and the natural aging of each generation.

Gen-B – postwar baby-boomers (in green) – are not much affected by net immigration since 2010. So, their deaths have reflected both the natural aging process and the behaviour changes (partly enforced) in 2020 arising from the Covid19 pandemic. We also see an impact of the 2017 influenza epidemic.

I am calling the generation who were babies or young children during World War 2 ‘Gen-W’. Shown in purple, Gen-W were clearly and adversely affected by the 2017 influenza epidemic. In 2021, many Gen-W people died who would have died in 2020 had 2020 been a normal year. We also note that death increases in 2022, while marked, are less marked than the three younger generations. This is because Gen-W is a diminishing generation, with deaths in previous years impacting substantially on the living Gen-W population.

This last impact is most prominent for Gen-D (children of the Depression), who saw substantially fewer deaths in 2020 and 2021, largely because of there being fewer of them, but also because of the pandemic public health measures.

In coming years, most likely the main determinant of increasing numbers of deaths in each birth cohort will be that natural aging of that cohort/generation. But high levels of both immigration and emigration will continue to play a role, as will ‘health crises’ arising from both changes in the health statuses of the generations, and arising from compromised health-care services.

*******

Keith Rankin (keith at rankin dot nz), trained as an economic historian, is a retired lecturer in Economics and Statistics. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand.