Analysis by Keith Rankin.

In the European Union at least, mortality data is now available until close to the end of 2023. In northern Europe, mortality has been markedly higher than it should have been in the ‘Fall’ – autumn – of 2023. The main exception is Poland. Respiratory illness is most likely the culprit.

My working hypothesis is that excess deaths since mid-2021 have been mainly due to reduced immunity – general and covid specific – and that the extent of deficient immunity is largely a function of the duration of ‘public health’ lockdowns and facemask mandates. Other contributing factors would be the severity of the viruses in circulation, and the numbers of people vulnerable due to age or pre-infective morbidity.

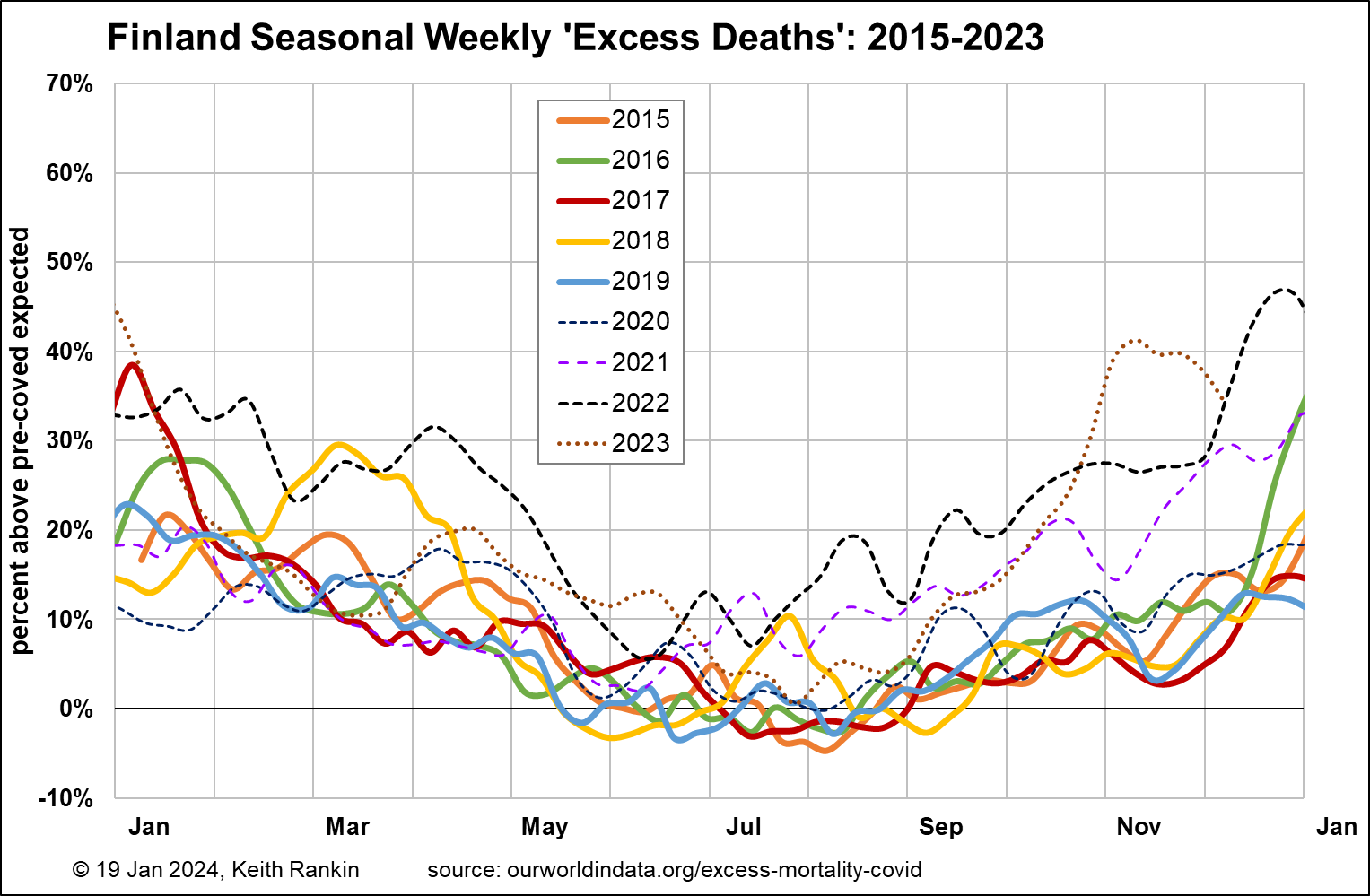

Finland seems to have been hit particularly hard and early, this autumn. The deaths suggest an outbreak of Covid19 or something else towards the end of September. Finland fits the working hypothesis, with little sign of a Covid19 impact until mid-2021, and then a consistent pattern of excess deaths. Finland’s population is looking distinctly unhealthy, and with no evidence yet that 2024 will be much better. Finland had probably the strictest public health barrier mandates (lockdowns and facemasks) of all the Scandinavian countries.

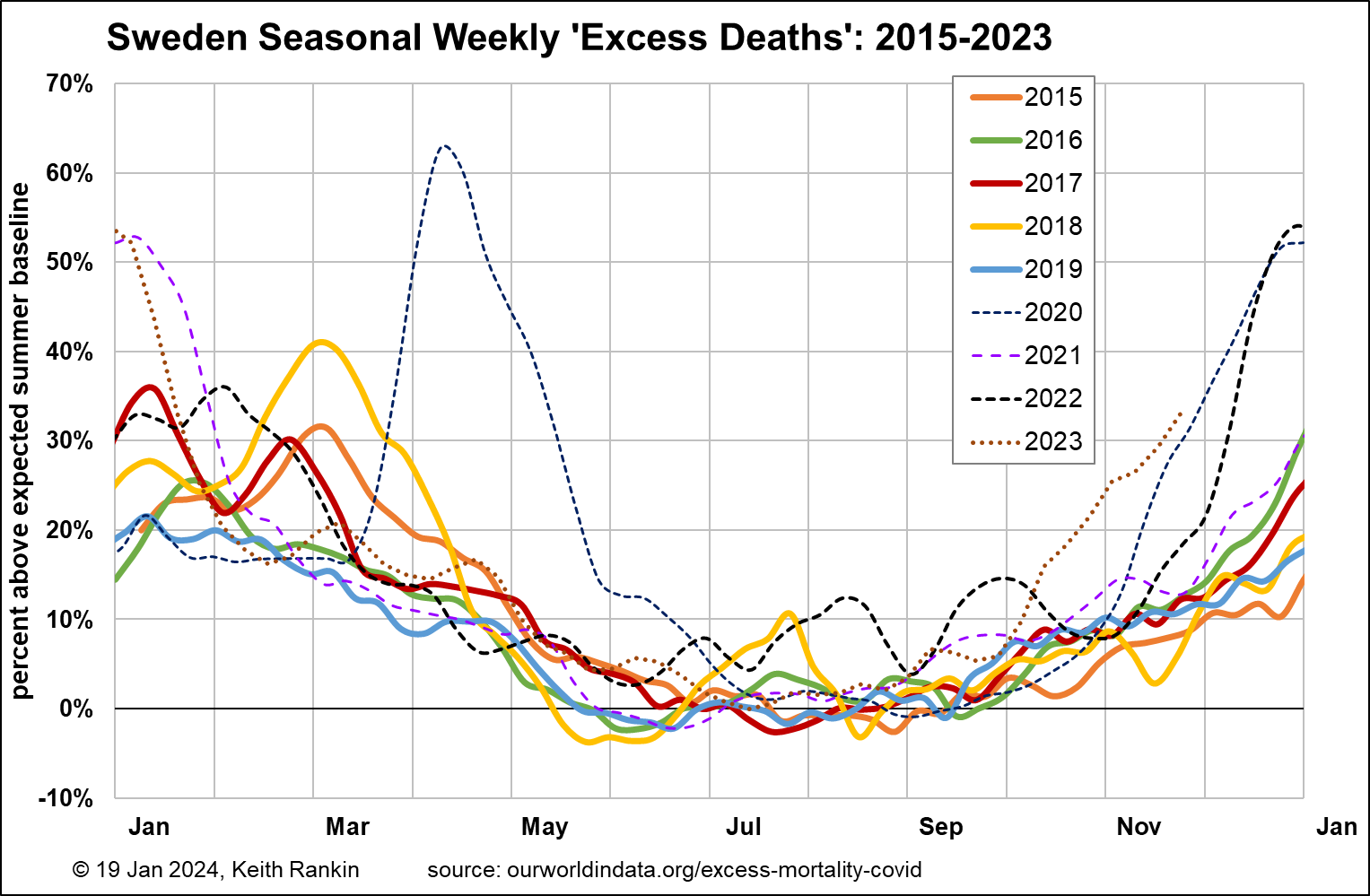

Sweden is the opposite of Finland, with substantial excess mortality in 2020 and January 2021. From February 2021, Sweden’s mortality has looked normal. There were 2022 mortality waves synchronous with Finland, but smaller and briefer (except December 2022 which was high throughout Europe). Sweden has caught the autumn 2023 wave, but later and not as seriously as Finland. We’ll watch to see if there was a mortality fall-off there in December. (We note Sweden had a particularly benign 2019, meaning that it had in 2020 a group of older people who would have died in 2019 had 2019 been a normal year.)

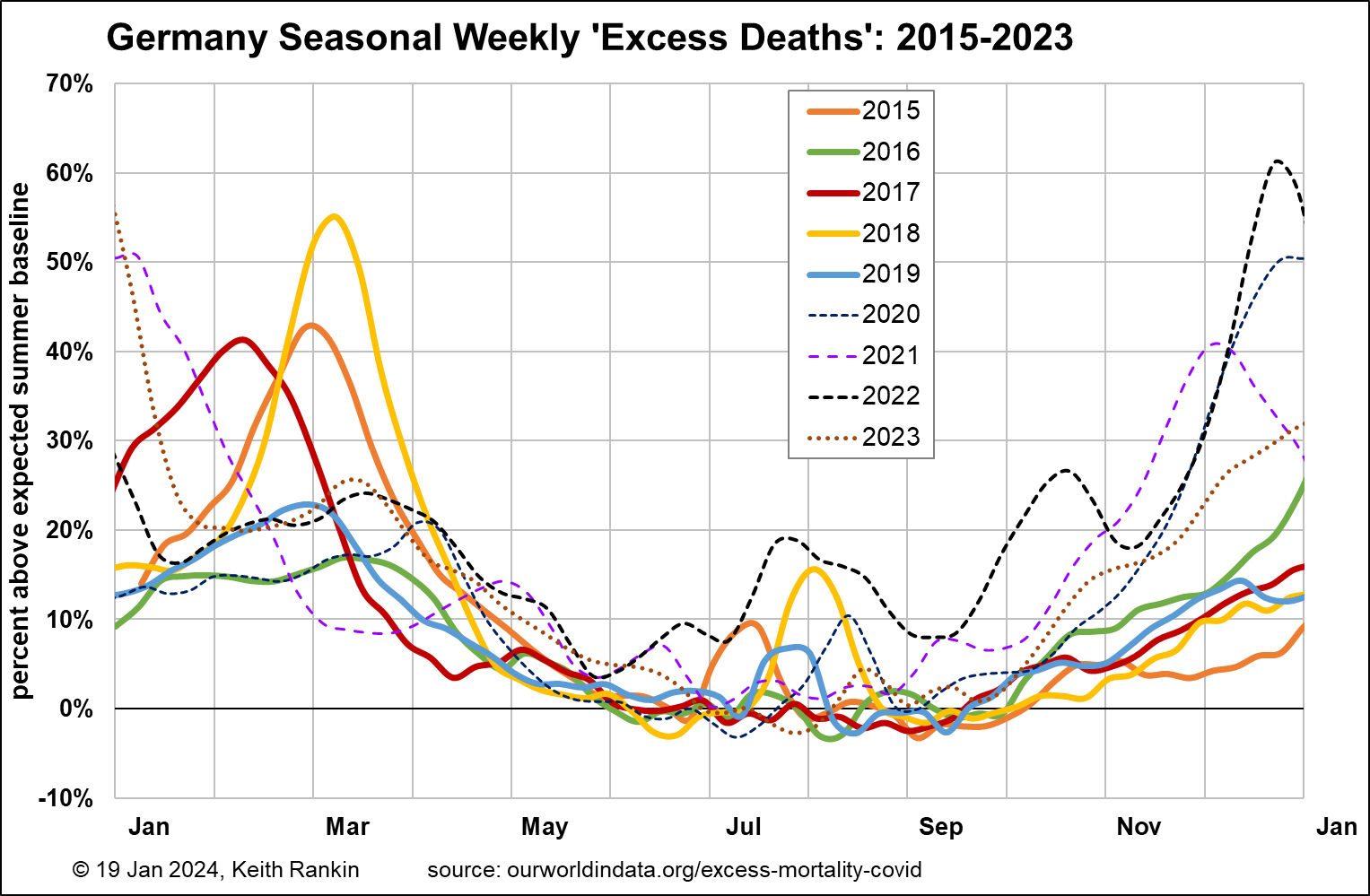

Germany looks much like Finland, except that it experienced the winter 2020/21 wave which Finland avoided due to its public health restrictions. Germany experienced a ‘spiral of death’ in the second half of 2022. While most of 2023 has been about normal in Germany, the autumn mortality wave was serious and possibly ongoing. Germany is a country with weakened immunity, at least according to my hypothesis (given its extensive and prolonged public health barrier mandates), and which seems to have been exposed to the worst of whatever viruses – or virus strains – have been circulating recently.

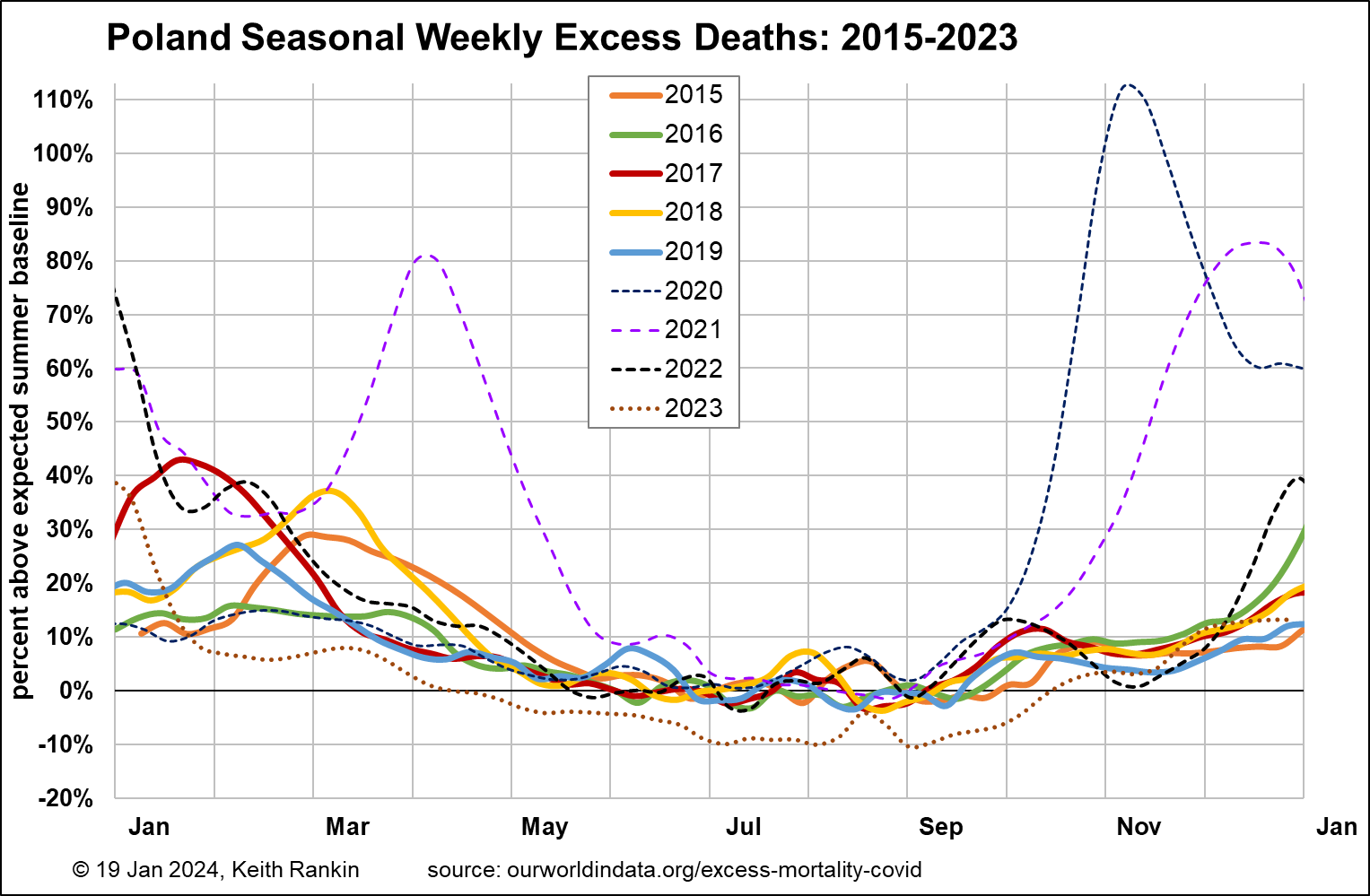

Poland appears to be an enigma, though it does fit my working hypothesis. Poland showed no significant Covid19 mortality until September/October 2020. Like other Eastern European countries, it suffered twice as much as Western Europe in the winter of 2020/21. This, I have hypothesised, is due to the substantially weakened levels of general immunity in East Europe in the fall of 2020. Poland also suffered severely from waves of Covid19 in the spring of 2021 and the winter of 2021/22. Then, in 2022, Omicron Covid19 seems to have acted as a natural vaccination, making its experience much less severe than the experiences of Germany and Finland. 2023 looks to have been particularly benign in Poland.

We should note that Poland’s elderly took a hammering in 2020 and especially 2021, so there were fewer of them in 2022 and 2023. But, all of Eastern Europe has an older population, especially of postwar baby-boomers, in large part because the has been a westward drain of younger people. Poland’s population remains ‘oldish’, despite the demographic ‘haircut’ faced by that country in 2021. It’s population now looks remarkably healthy; presumably with high restored levels of general immunity.

(Another problematic country of North Europe, not shown here, is Ireland. Ireland imposed greater public health restrictions than the United Kingdom, but, like Finland, has had a distinctly queasy time of it since July 2021. Before the British pillory their government too much over its Covid19 public health response, a good comparative analysis, looking at all four years from 2020 to 2023, might suggest that the excess mortality data in the United Kingdom may not have been much better had they adopted a different set of public health policies.)

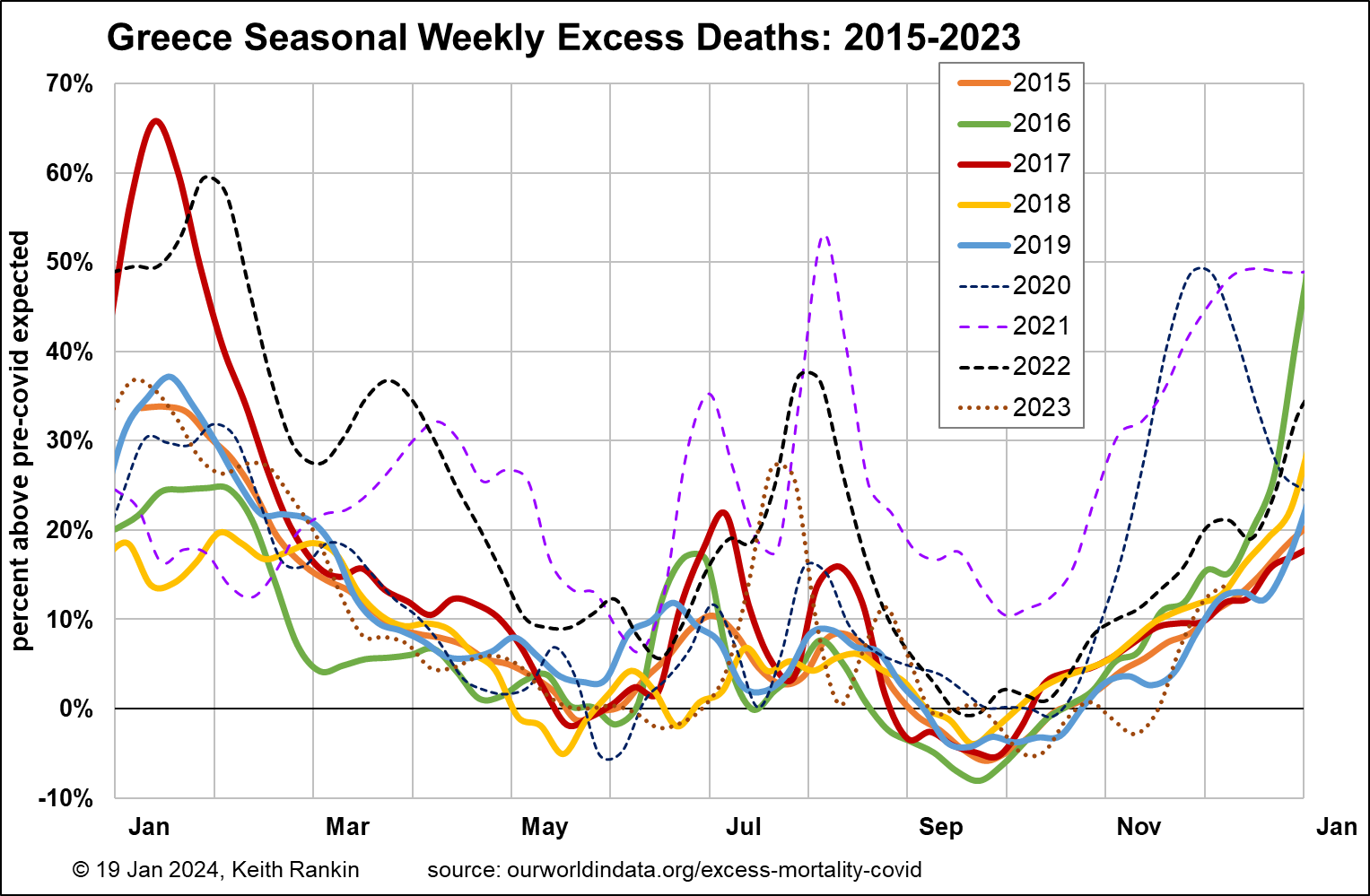

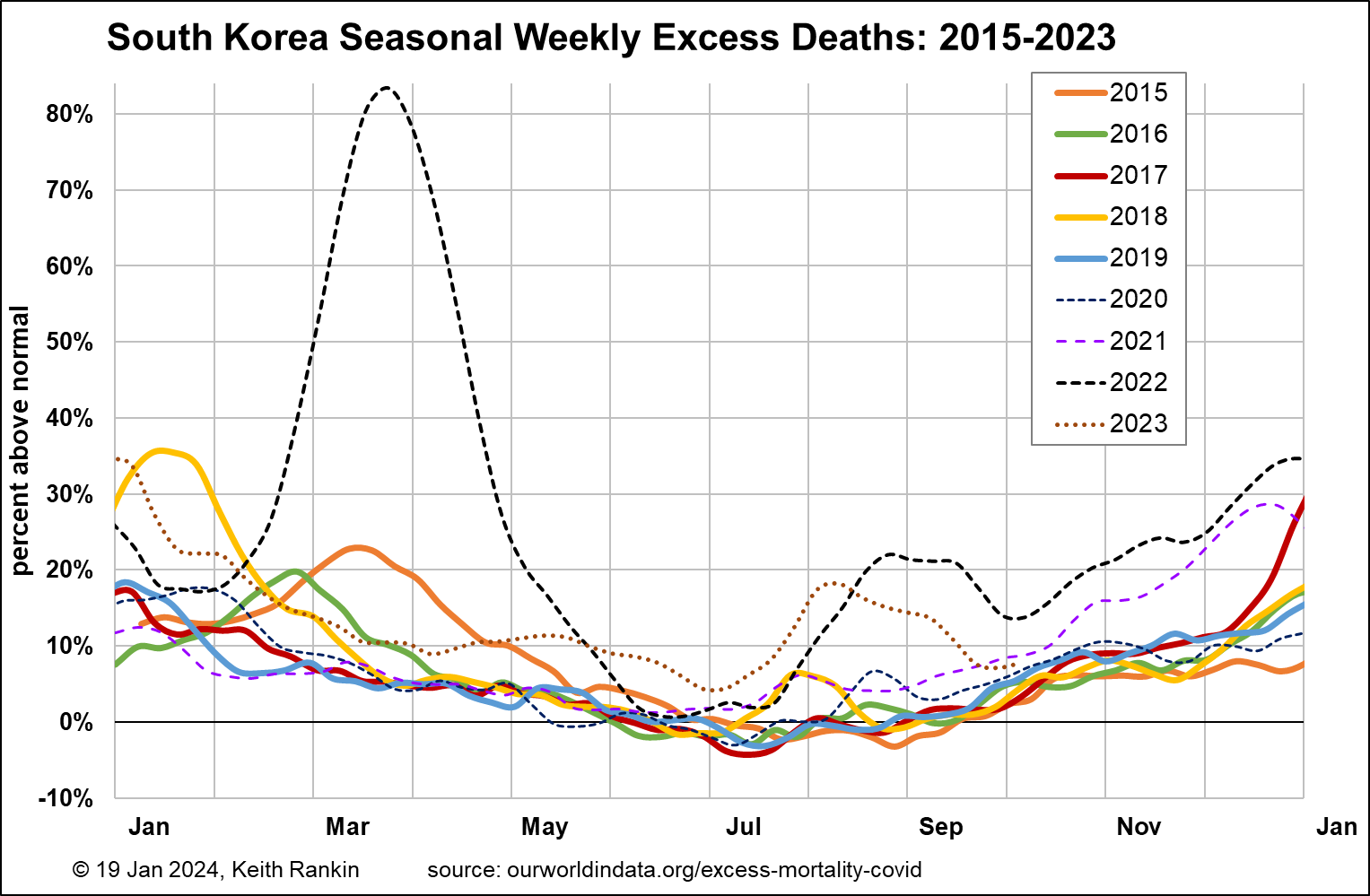

For interest, I have added charts for Greece and South Korea.

Greece got Covid19 late, and had a bad 2021, though not as bad as Poland. Early 2022 was worse in Greece though. We also note that Greece is unusual, because it has substantial summer death waves. Most of this will be due to the numbers of people passing through Greece, in the context that its visitor-to-local population ratio is unusually high each summer. Then, in 2022 and 2023 there were the big wildfires, which also contributed to excess mortality. There is no sign of excess mortality in Greece this autumn. It may not have received much of the virus infectivity that has been apparent in the north. Or, Greeks may have better restored their levels of general immunity than have Finns and Germans.

Finally, South Korea has this remarkable picture of having been little affected by Covid19 – at least in the death data – from March 2020 until July 2021. (It did have a significant early outbreak, in February 2020.) Things started to go wrong in Korea after July 2021, followed by a fullscale deathwave from February to April 2022. This was the less-severe Omicron variant, so clearly the Korean population was not prepared; Koreans must have had very low natural and vaccination immunity, owing to excessive and prolonged facemask wearing (and an insufficiency of vaccination boosters). Further, South Korea has had significant excess deaths since August 2022. It’s too early to say how the northern hemisphere autumn wave has affected South Korea; that country is tardy in releasing its data.

For the most part the data fits my working hypothesis, although Sweden is starting to converge more with its Nordic neighbours, all of which followed more restrictive policies. Sweden continues to have large numbers of very old people, reflective of its early exit from the Great Depression and its neutrality in World War Two.

(And, just an aside, it’s remarkable how many very old people are still alive in Japan, given its World War Two experience. Indeed I have visited the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum, which I thought gave a very fair representation of the events of the war in Japan. And I visited the ‘ground zero’ Hypocenter Park. Sobering. Many Japanese will have survived due to the lack of a protracted ground war in that country. Korea, on the other hand, has a demographic structure significantly more determined by both World War Two and the active historical phase of the Korean War. South Korea’s excess mortality might have been substantially greater had it had a full quota of octogenarians and nonagenarians.)

*******

Keith Rankin (keith at rankin dot nz), trained as an economic historian, is a retired lecturer in Economics and Statistics. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand.