Analysis by Keith Rankin.

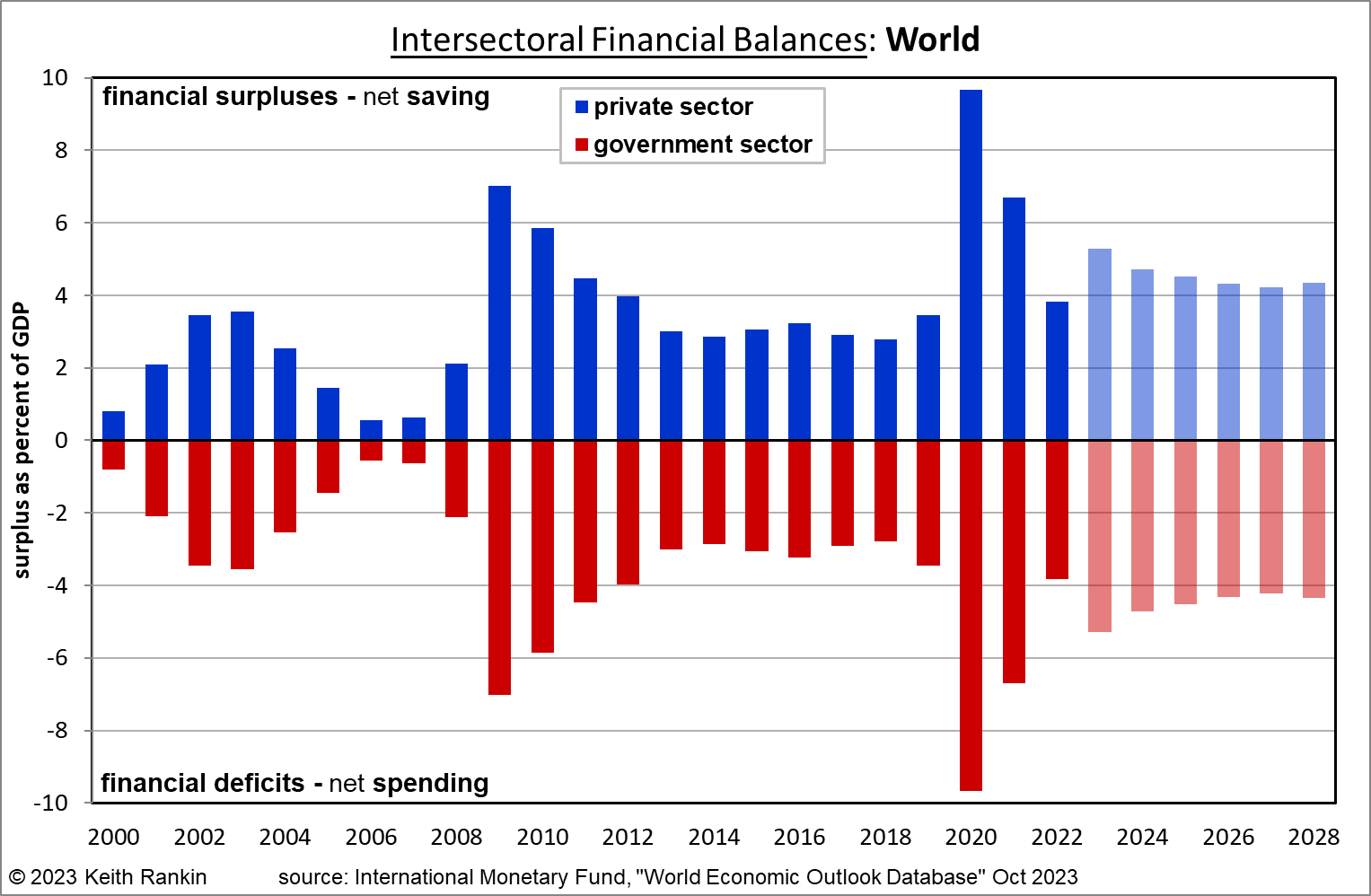

The above chart shows that the world’s governments, taken collectively, run financial deficits every year. This is not a weakness of the global financial system; it’s a strength, perhaps the strength of the world system. Government deficits offset private sector financial choices.

We note that when the world government deficit becomes unusually small, as in 2000 and 2006/07, the world’s financial system is at its least stable. 2000 to 2001 was the dotcom financial bust, and 2008/09 was the global financial crisis. These small crisis-preceding deficits are a result of substantial speculative activity accruing in some portions of the private sector, reducing overall private surpluses; essentially larger than usual amounts of private speculative borrowing.

After a financial crisis – indeed as a playing-out of such a crisis – the private sector (defined as combined non-government financial participants) runs unusually large financial surpluses which must be accommodated by government deficits. Any economic recession which follows a financial crisis indicates insufficient government accommodation of private retrenchment.

Those large private financial surpluses were not as large as the panicked parties would like them to have been. As a result of a financial crisis, private participants seek to pay down as much debt as they can as quickly as they can, and most reduce investment spending in favour of increased saving. The extent to which private parties can achieve their distress goals is determined by governments’ willingness to extend government debt and to run down sovereign (and local government) wealth funds.

Not all economic crises commence with a financial crisis. We see the size of the Covid19-led crisis in the 2020 balances. In this case, it was the governments who initiated their increased deficits by becoming much more willing to borrow than usual, though in a financial environment that was making the private sector much less willing to borrow. So the private sector was very happy in 2020 to underwrite new government debt.

It’s worth noting the IMF’s forecasts for 2023 to 2028 (shown in muted colours). These forecasts are conservative. While I think the post-covid recovery was on the way to creating a financially speculative environment (such as in 2005), the subsequent wars will probably lead to 2023 and 2024 balances similar to 2018 rather than to 2007.

While I think it very likely that there will be a new Great Depression commencing as soon as 2026, rather than a financial crisis the lead-up will be the military/environmental cost-crisis which is already well under way; a crisis that I imagine will precipitate a global stagflation in the later 2020s. (We note that military costs are threefold: economic activity diverted from peacetime into military production; the fact that an active military substantially exacerbates the existing environmental crises which include excessive greenhouse gas emissions; and the military destruction of human beings, ecosystems, housing, and public utility infrastructure.) In other words, the financial lead-up to the next economic crisis may be more like the lead-up to the covid pandemic crisis; nevertheless, we should look out for elements of excessive financial speculation in 2024 and 2025.

(Note on source data. The IMF does not provide World balances directly. But they do provide balances separately for advanced economies and for emerging/developing economies. The data shown is a weighted average of these two groups, with combined advanced countries having a 70% weight and emerging a 30% weight. Changing those weights would not make much difference to the chart.)

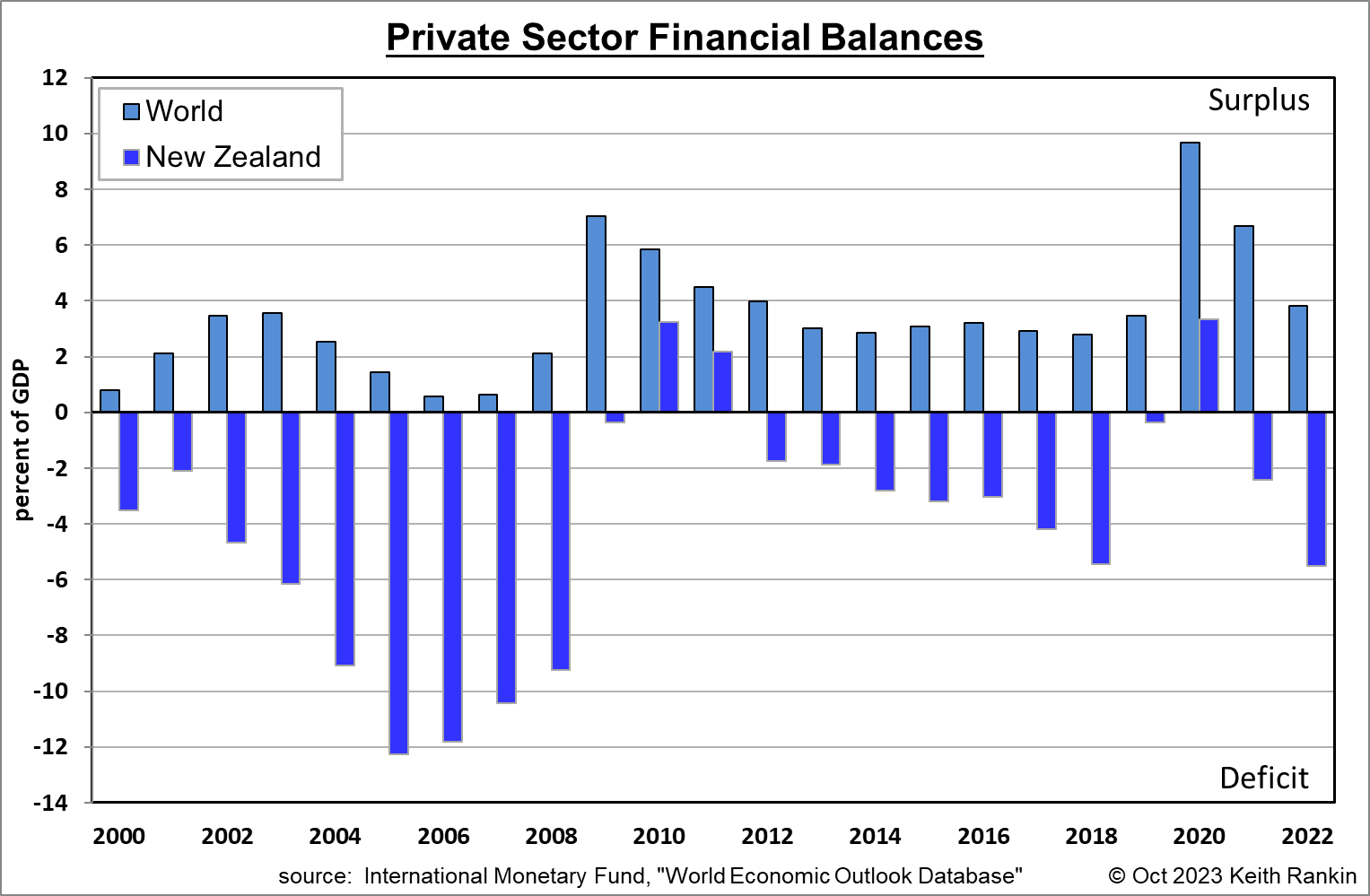

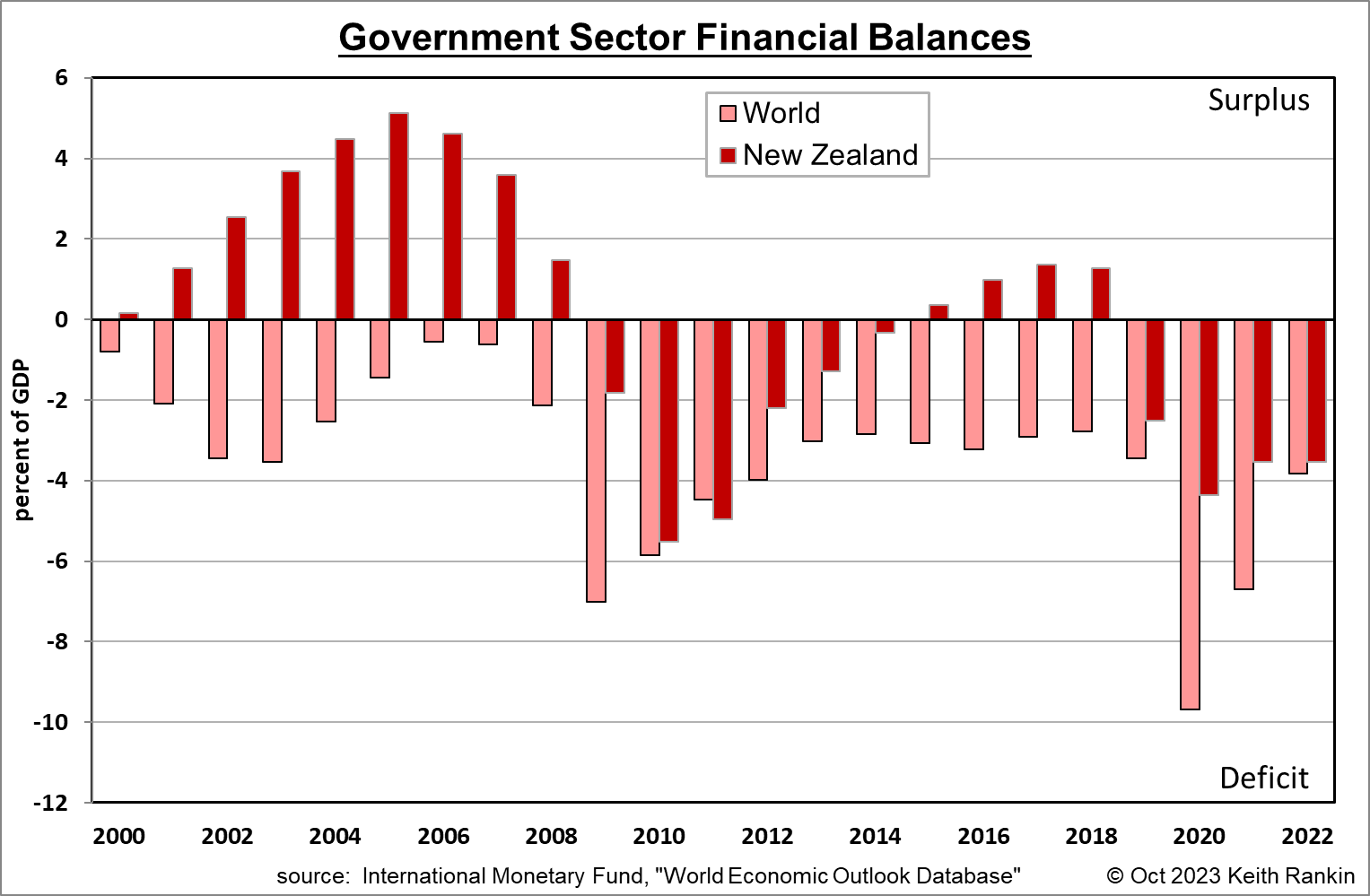

I finish here with two charts which show just how exceptional New Zealand’s financial balances have been:

(A country’s government balance is not the exact opposite of its private balance, because a country – but not the world – also has foreign balances.)

We see that New Zealand’s private sector financial sector balances are typically negative (ie deficits); in contrast with the world, which shows positive financial balances (surpluses) each year. Sometimes these private deficits are very large. (We note that, due to a technicality, 2019 New Zealand data are contaminated by data from the first half of 2020 – meaning the initial phases of the pandemic.)

New Zealand’s exceptionalism is less apparent in the chart showing government balances for New Zealand and the world. But the exceptionalism is still clearly there; except for the crisis years at the turn of each decade within this century.

If most other countries had tried to follow New Zealand’s long-term financial model then the world economy would be in perpetual crisis. But New Zealand’s exceptional strategy does work because it is exceptional, because most others do not follow it; indeed New Zealand’s strategy offsets the very different financial strategies followed by most other advanced countries. When some countries follow one kind of destabilising strategy and others follow the opposite kind of destabilising strategy, then indeed two wrongs can make a right.

*******

Keith Rankin (keith at rankin dot nz), trained as an economic historian, is a retired lecturer in Economics and Statistics. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand.