SPECIAL REPORT: By Yamin Kogoya

The referendum on the indigenous Voice in Australia last Saturday was an historic event. Australians were asked to vote on whether to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia in the Constitution through an indigenous Voice.

The voters were asked to vote “yes” or “no” on a single question:

“A Proposed Law: to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

“Do you approve this proposed alteration?”

The Voice was proposed as an independent, representative body for First Nations peoples to advise the Australian Parliament and government, giving them a voice on issues that affect them.

Here are some key points:

- The proposal was to recognise Indigenous Australians in the Constitution by creating a body to advise Parliament, known as the “Voice”.

- The “Voice” would be an independent advisory body. Members would be chosen by First Nations communities around Australia to represent them.

- The “Voice” would provide advice to governments on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, such as health, education, and housing, in the hope that such advice will lead to better outcomes.

- Under the Constitution, the federal government already has the power to make laws for Indigenous people. The “Voice” would be a way for them to be consulted on those laws. However, the government would be under no obligation to act on the advice.

- Indigenous people have called for the “Voice” to be included in the Constitution so that it can’t be removed by the government of the day, which has been the fate of every previous indigenous advisory body. It is also the way indigenous people have said they want to be recognised in the constitution as the First Nations with a 65,000-year connection to the continent — not simply through symbolic words.

It was necessary for a majority of voters to vote “yes” nationally, as well as a majority of voters in at least four out of six states, for the referendum to pass.

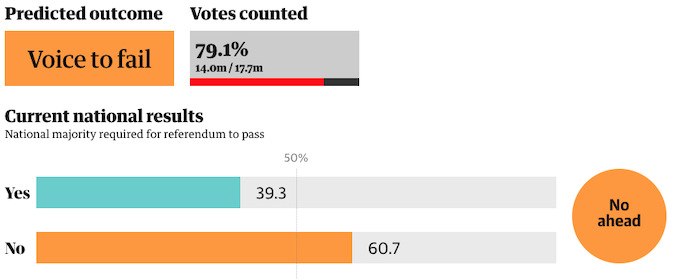

Unfortunately, it was rejected by the majority with more than 60 percent with the vote still being counted. In all six states and the Northern Territory, a “No” vote was projected.

According to the ABC, a majority of voters in all six states and the Northern Territory voted against the proposal.

New South Wales

81.2 percent counted, 1.81 million voted yes (40.5 percent) and 2.67M million voted no (59.5 percent).

Victoria

78.5 percent counted, 1.56 million voted yes (45.0 percent), and 1.91 million voted no (55.0 percent).

Tasmania

82.7 percent counted, 134,809 voted yes (40.5 percent), and 198,152 voted no (59.5 percent).

South Australia

79.1 percent counted, 355,682 voted yes (35.4 percent), 648,769 voted no (64.6 percent).

Queensland

74.3 percent counted, 835,159 voted yes (31.2 percent), 1.84 million voted no (68.8 percent).

Western Australia

75.3 percent counted, 495,448 voted yes (36.4 percent), and 866,902 voted no (63.6 percent).

Northern Territory

63.4 percent counted, 37,969 voted yes (39.5 percent), and 58,193 voted no (60.5 percent).

ACT

82.8 percent counted, 158,097 voted yes (60.8 percent), and 102,002 voted no (39.2 percent).

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has said the next steps after the failed Indigenous Voice to Parliament referendum are yet to be decided and called the expectation of having a plan just days after the vote “not respectful”.

For the latest news, visit: https://t.co/X6qtu24rNp pic.twitter.com/smgqgeV55Y

— SBS News (@SBSNews) October 17, 2023

In addition to being viewed as divisive along racial lines, concerns about how the Voice to Parliament would work (whether indigenous Australians would be given greater power) and uncertainties about how the new body would result in meaningful change for indigenous Australians contributed to the rejection.

Australia has held 44 referendums since its founding in 1901. However, the referendum on the Indigenous Voice to Parliament in 2023 was the first of its kind to focus specifically on Indigenous Australians.

As part of a broader push to establish constitutional recognition of Indigenous Australians, the Voice proposal was seen as a significant step towards reconciliation and was the result of decades of indigenous advocacy and work.

A key turning point came in 2017 when 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander delegates from across the country met at Uluru for the First Nations’ National Constitutional Convention. The proposal, known as the Voice, sought to recognise Indigenous people in Australia’s constitution and establish a First Nations body to advise the government on issues affecting their communities.

However, the Voice proposal was not unanimously accepted. In the course of the campaign, intense conflict and discussion ensued between supporters and opponents, resulting in what supporters viewed as a tragic outcome, while the victorious opponents celebrated their victory.

The support of Oceania’s indigenous leaders

Pacific Islanders expressed their views before the referendum on the Voice to Parliament.

Henry Puna, Secretary-General of the Pacific Islands Forum, said that Australia’s credibility would be boosted on the world stage if the yes vote won the Indigenous voice referendum. He stated that it would be “wonderful” if Australia were to vote yes, because he believed it would elevate Australia’s position, and perhaps even its credibility, internationally.

The former Foreign Minister of Vanuatu (nd current Climate Change Minister), Ralph Regevanu, warned Australia’s reputation would plummet among its allies in the Pacific if the Voice to Parliament was defeated.

These views indicate the potential impact of the voice referendum on Australia’s relationship with Pacific Island nations, which it often refers to as “its own backyard”.

The “No” camp claimed the Voice was an “elite” idea, that “real” Indigenous people didn’t want it, because Peter Dutton had spoken to “shoppers”. Even with the results, they still insist communities did not want one – taking away what little voice they gothttps://t.co/kWt0hjDHEC

— Rachel Withers (@rachelrwithers) October 17, 2023

Division, defeat and impact

A tragic aspect of the Voice proposal is the fact that not only were Australian settlers divided about it, but even worse, indigenous leaders themselves, who were in a position to bring together a fragmented and tormented nation, were at odds with each other — including full-on verbal wars in media.

While their opinions on the proposal were divided, some had practical and realistic ideas to address the problems faced by indigenous communities in remote towns. Others proposed a treaty between settlers and original indigenous people.

There are also those who advocate for a strong political recognition within the nation’s constitutional framework.

Despite these divisions among indigenous leaders, the referendum on Voice represents a significant milestone in the ongoing indigenous resistance that spans over 200 years.

It is a resistance that began on January 26, 1788, when the invasion began (Pemulwuy’s War), and continued through various milestones such as the 1937 Petition for citizenship, land rights, and representation, the 1938 Day of Mourning, the 1963 Yirrkala bark petitions, the 1965 Freedom Rides, and the establishment of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra in 1972.

It further extended to 1990-2005 with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC), the 1991 Song Treaty by Yothu Yindi, Eddie Mabo overturning terra nullius in 1992, Kevin Rudd’s 2008 apology, and the Uluru Statement from the Heart until the recent defeat of the Voice Referendum in 2023.

A dangerous settlers’ myth and its consequences

The modern nation of Australia (aged 244 years) has been shaped by one of European myths: “Terra Nullius”, the Latin term for “nobody’s land”. This myth was used to describe the legal position at the time of British colonisation.

Accordingly, the land had been deemed as terra nullius, which implies that it had belonged to no one before the British Crown declared sovereignty over it.

Eddy Mabo: A Melanesian Hero

An indigenous Melanesian, Eddy Mabo, overturned this myth in 1992, known as “the Mabo Case,” which recognised the land rights of the Meriam people and other indigenous peoples.

The Mabo Case resulted in significant changes in Australian law in several areas. One of the most notable changes was the overturning of the long-standing legal fiction of “terra nullius,” which posited that Australia was unpopulated (no man’s land) at the time of British colonisation.

In this decision, the High Court of Australia recognized the legal rights of Indigenous Australians to make claims to lands in Australia. It marked a historic moment, as it was the first time that the law acknowledged the traditional rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. In addition, the Mabo Case contributed directly to the establishment of the Native Title Act in 1993.

Even though these changes are significant, debates persist regarding the state of indigenous Australians under colonial settlement.

Indigenous Affairs reporter Isabella Higgins says the No victory in the Indigenous Voice to Parliament Referendum could change the way Indigenous Australians will want to interact with the rest of the country going forward. pic.twitter.com/g5CxBaU0Op

— ABC News (@abcnews) October 15, 2023

Indigenous leaders need to see a big picture

The recent referendum on the Voice sparked heated debates on a topic that has long been a source of contention: the age-old battle of “my country versus your country, my mob versus your mob, I know best versus you know nothing.”

While it’s important to celebrate and protect cultural diversity and the unique perspectives it brings, it’s equally important to recognise that British settlers didn’t just apply the myth of terra nullius to a select few groups or regions — they applied it to all areas inhabited by indigenous peoples, treating them as a single, homogenous entity.

This means that any solution to indigenous issues must be rooted in a collective, unified voice, rather than a patchwork of fragmented groups.

Indigenous leaders need to prioritise the creation of a unified front among themselves and mobilise their people before seeking support from Australians. Currently, they are engaging in competition, outdoing each other, and fighting over the same issue on mainstream media platforms, indigenous-run media platforms, and social media.

This approach is reminiscent of the “divide, conquer, and rule” strategy that the British effectively employed worldwide to expand and maintain their dominion. This strategy has historically caused harm to indigenous nations worldwide, and it is now harming indigenous people because their leaders are fighting among themselves.

It is important to note that this does not imply a rejection of every distinct indigenous language group, clan, or tribe. However, it is crucial to recognise that indigenous peoples throughout Oceania were viewed through a particular European lens, which scholars refer to as “Eurocentrism”.

This “lens” is a double-edged sword, providing semantic definition and dissection power while also compartmentalising based on a hierarchy of values. Melanesians and indigenous Australians were placed at the bottom of this hierarchy and deemed to be of no historical or cultural significance.

This realisation is of utmost importance for the collective attainment of redemption, unity and reconciliation.

The larger Australian indigenous’ cause

From Vasco Núñez de Balboa’s momentous crossing of the Isthmus of Panama to Ferdinand Magellan’s pioneering Spanish expedition across the Pacific Ocean in 1521, and Abel Janszoon Tasman’s remarkable exploration of Tasmania, Australia, New Zealand, and Fiji, to James Cook’s renowned voyages in the Pacific Ocean between 1768 and 1779, the indigenous peoples of Oceania have endured immense suffering and torment as a consequence of the European scramble for these territories.

The indigenous peoples of Oceania were forever scarred by the merciless onslaught of European maritime marauders. When the race for supremacy over these unspoiled regions unfolded, their lives were shattered, and their communities torn asunder.

The web of life in Australia and Oceania was severely disrupted, devalued, rejected, and subjected to brutality and torment as a result of the waves of colonisation that forcefully impacted their shores.

The colonisers imposed various racial prejudices, civilising agendas, legal myths, and the Discovery doctrine, all of which were conceived within the collective conceptual mindset of Europeans and applied to the indigenous people.

These actions have had a lasting and fatalistic impact on the collective indigenous population in Australia and Oceania, resulting in dehumanisation, enslavement, genocide, and persistent marginalisation of their humanity, leading to unwarranted guilt for their mere existence.

The European collective perception of Oceania, exemplified by the notion of terra nullius, has resulted in numerous transgressions of indigenous laws, customs, and cosmologies, affecting every aspect of life within the entire landscape. These violations have led to the loss of land, destruction of language, erasure of memories, and imposition of British customs.

Furthermore, indigenous peoples were forcibly relocated to concentration camps, missions, and reserves.

The Declaration received support from a total of 144 countries, with only four countries (which have historically displaced indigenous populations through settler occupation) voting against it — Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States.

However, all four countries subsequently reversed their positions and endorsed the Declaration. It should be noted that while the Declaration does not possess legal binding force, it does serve as a reflection of the commitments and responsibilities that states have under international law and human rights standards.

The challenges and concerns confronting indigenous communities are undeniably more severe and deplorable than the current “yes or no” referendum. It is imperative for the entire nation, including indigenous leaders, to acknowledge the profound extent of the Indigenous human tragedy that extends beyond the divisive binary.

Old and new imperial vultures

Similar to the European vultures that once encircled Oceania centuries ago, partitioned its territories, subjugated its people, conducted bomb experiments, and eradicated its population in Tasmania, the present-day vultures from the Eastern and Western regions exhibit comparable behaviours.

It is imperative for indigenous leaders hailing from Australia, Melanesia, Polynesia, and Micronesia to unite and demand that the colonial governments be held responsible for the multitude of crimes they have perpetrated.

Message to divided indigenous leaders

Simply assigning blame to already fragmented, tormented, and highly marginalised Indigenous communities, and endeavouring to empower them solely through a range of government handouts and community-based development programs, will not be adequate.

Because the trust between indigenous peoples and settlers has been shattered over centuries of abuse, deeply impacting the core of Indigenous self-image, dignity, and respect.

My personal experience in remote indigenous communities

I am a Papuan who came to Australia over 20 years ago to study in the remote NSW town of Bourke. I lived, studied, and worked at a small Christian College called Cornerstone Community.

During my time there, I was adopted by the McKellar clan of the Wangkumara Tribe in Bourke and worked closely with indigenous communities in Bourke, Brewarrina, Walgett, Cobar, Wilcannia, and Dubbo.

Unfortunately, my experiences in these places left me traumatised.

These communities have become so broken. I found myself succumbing to depression as a result of the distressing experiences I witnessed. It dawned upon me being “blackfella” — Papuan indigenous descent — was and still consistently subjected to similar mistreatment regardless of location.

This realisation instilled within me a sense of guilt for my own identity, as I was constantly made feel guilty of who I was. Tragically, a significant number of the young indigenous whom I endeavoured to aid and guide through diverse community and youth initiatives have either been incarcerated or committed suicide.

West Papua, my home country, is currently experiencing a genocide due to the Indonesian settler occupation, which is supported by the Australian government. This is similar to what indigenous Australians have endured under the colonial system of settlers.

Indigenous Australians in every region, town, and city face a complex and diverse set of issues, which are unique, tragic, and devastating. These issues are a result of how the settler colony interacted with them upon their arrival in the country.

Nevertheless, the indigenous people were not subjected to centuries of abuse and mistreatment solely based on their tribal affiliations. Rather, they were targeted by the settler government as a collective, disregarding the diversity among indigenous groups.

This included the indigenous people from Oceania, who have endured dehumanisation and racism as a result of colonisation.

It is imperative to acknowledge that the resolution of these predicaments cannot be attained by a solitary leader representing a particular group. The indigenous leaders need a unified vision and strategy to combat these issues.

All indigenous individuals across the globe, including Australia, New Zealand, Oceania, and West Papua, are afflicted by the same affliction. The only distinguishing factor is the degree of harm inflicted by the virus, along with the circumstances surrounding its occurrence.

A statement from Indigenous Australians who supported the Voice referendum. https://t.co/UlW2kvd9oa pic.twitter.com/1159uz3bxk

— ulurustatement (@ulurustatement) October 15, 2023

A paradigm shift

Imagine a world where indigenous peoples in Australia and Oceania reclaim their original languages and redefine the ideas, myths, and behaviours displayed on their land with their own concepts of law, morality, and cosmology. In this world, I am confident that every legal product, civilisational idea, and colonial moral code applied to these peoples would be deemed illegal.

It is time to empower indigenous voices and perspectives and challenge the oppressive systems that have silenced them for far too long.

Commence the process of renaming each island, city, town, mountain, lake, river, valley, animal, tree, rock, country, and region with their authentic local languages and names, thereby reinstating their original significance and worth.

However, in order to accomplish this, it is imperative that indigenous communities are granted the necessary authority, as it is ultimately their power that will reinforce such transformation. This power does not solely rely on weapons or monetary resources, but rather on the determination to preserve their way of life, restore their self-image, and demand the recognition of their dignity and respect.

Last Saturday’s No Vote tragedy wasn’t just about the majority of Australians rejecting it. It was a heartbreaking moment where indigenous leaders, who should have been united, found themselves fiercely divided.

Accusations were flying left and right, targeting each other’s backgrounds, positions, and portfolios. This bitter divide ended up gambling away any chance of redemption and reconciliation that had reached such a high national level.

It was a devastating blow to the hopes and aspirations for a better world for one of the most disadvantaged originals continues human on this ancient timeless continent — Australia.

Yamin Kogoya is a West Papuan academic who has a Master of Applied Anthropology and Participatory Development from the Australian National University and who contributes to Asia Pacific Report. From the Lani tribe in the Papuan Highlands, he is currently living in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz