Analysis by Keith Rankin.

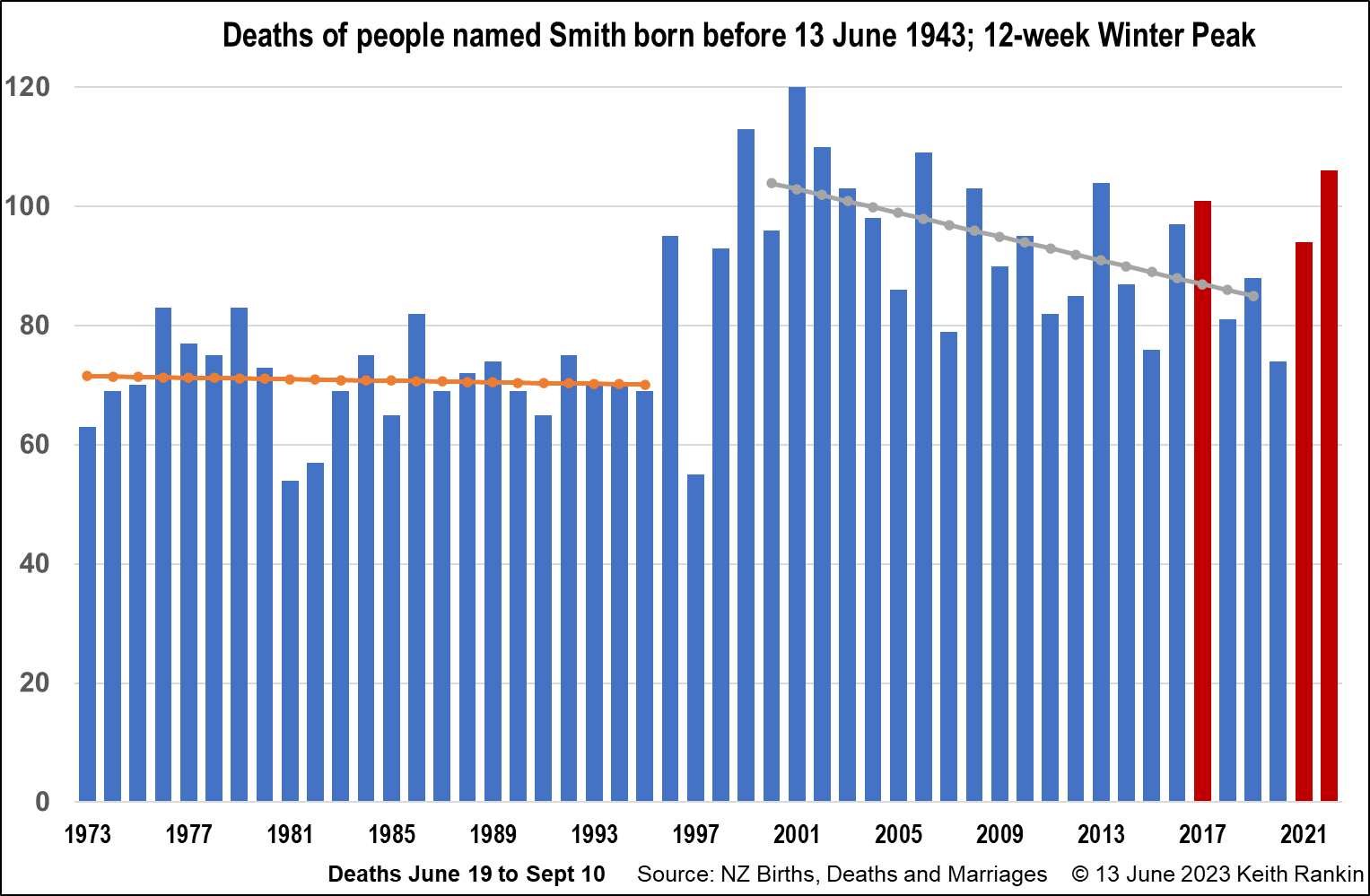

The above chart draws on the historical ‘births, deaths, and marriages’ dataset published by the Ministry of Internal Affairs. It’s a major resource for genealogical research.

The database for 13 June 2023 showed the deaths of all people whose deaths were registered in New Zealand on or before 13 June 1973. And, for 14 June 1973 to 13 June 2023, the deaths of people born on or before 13 June 1943. You need to enter a family name – and ‘wildcard’ spellings are not allowed – so I have used the name Smith as a sample of New Zealanders. (This dataset is useful in that you can get death numbers for individual dates, and it’s the date of death, not the date of registration. It would be good if you could use wildcards, as you can in most genealogical databases.)

The Smith sample used for the data for the above chart is biassed in several respects, but these biases are pertinent in the context of an evaluation of the demographic impact of the Covid19 pandemic in New Zealand.

The first and most obvious bias is that the data only includes older people; further the definition of ‘older’ changes for each year plotted, albeit in an orderly way. This in itself means that there will be more women counted, because the older population is more female. The second bias is that married women, including widows, will show up whether either their birth name or their final married name is ‘Smith’. So this survey is principally, though not only, of grandmothers (and great-grandmothers, and their sisters and female cousins).

The name Smith is a Pakeha name, common in Scotland as well as England, so will bias the data in favour of people (including many Māori) with English and Scottish ancestors. There will be bias against Māori though, because Māori life expectancy is still well below that for Pakeha. The octogenarian population underrepresents Māori. These factors will also bias the data in favour of the South Island relative to the North Island. Overall, this is very much a survey of the end-of-life circumstances of older Pakeha women in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The 2022 number includes people aged 79 and above who died in the 12-week period from 19 June to 10 September. The 2021 number includes people aged 78 and above who died in the 12-week period from 19 June to 10 September of that year. And so on. Thus the 1973 number includes people aged 30 or older when they died. Overall, the earlier the year the more younger person deaths; yet the overwhelming majority of deaths each year is of people who would have been regarded, when they died, as ‘elderly’.

The chart shows a discontinuity in the late 1990s, which I cannot explain for sure; a discontinuity that shows more Smith deaths in the early 2000s, when in fact I had expected fewer deaths. (Anti-vaxxers might interpret the discontinuity as being due to the introduction of the influenza vaccine. I think this is very unlikely to be the reason, and we would need numbers of people who actually received that vaccination each year. My suspicion is that significant numbers of people received influenza vaccinations only from the late-2000s.) My best guess is that in the early 2000s the most frequent ages of recorded deaths were the early 80s – from 80 to 82 years old. This corresponds to births in the 1920 to 1922 post World War 1 mini baby boom.

An important reason for this century’s trendline sloping downwards is the shortfall in births from 1932 to 1938, a result of the Great Depression. A person dying aged 89 (the most frequent age of death) in 2022 would have been born in 1932 or 1933, the peak years of the Depression. The deficit of births in the early 1930s would however have been offset to some extent by the immigration of ten-pound-poms in the 1950s and 1960s.

The peaks in the chart in most cases represent years of high levels of death from pneumonia and other conditions arising from winter respiratory infections, the most prominent being influenza though ‘common colds’ may also be significant triggers of mortality amongst people over 85 years old. (One year, 2013, appears to be a ‘rogue sample’ in which Smiths died, by chance, in greater numbers than would have been expected from overall deaths; a bad year for the Smith clan.)

The chart shows the impact of the deadly 2017 influenza ‘pandemic’, and it shows the substantial upturn in deaths in the winters of 2021 and 2022. The high 2022 number is known to be the mortality peak of Covid19 in New Zealand, a peak accentuated because most older people in New Zealand were required to wait too long for their second booster vaccination despite well-publicised forecasts of a winter peak. The high number in the chart for 2021 is more of a mystery, because neither Covid19 nor influenza were present in New Zealand that winter. The elevated number of deaths that year will be partly a reflection of the numbers of frail elderly who would have died in 2020 had that been a normal year; and partly older people with weakened immunity to common colds (arising from the lockdown and border quarantines).

The above chart shows the mortality experience in the last 50 years of, especially, older New Zealand women of Anglo-Scottish ancestry. Deaths have been falling in recent years due to both low birth numbers in the 1930s and to substantial health improvements enjoyed by New Zealanders born between 1918 and 1943. The trend from the late 2020s will be different, as post-1945 baby boomers start to appear in these kinds of data; and, possibly, as health improvements decline and quite possibly reverse in the face of increased inequality, which exists – especially around housing – among the older age cohorts as well as among families with young children. We protect older people by including them, not ignoring them.

Granny Smith had a good life. Long live Granny Smith.

*******

Keith Rankin (keith at rankin dot nz), trained as an economic historian, is a retired lecturer in Economics and Statistics. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand.