Analysis by Keith Rankin.

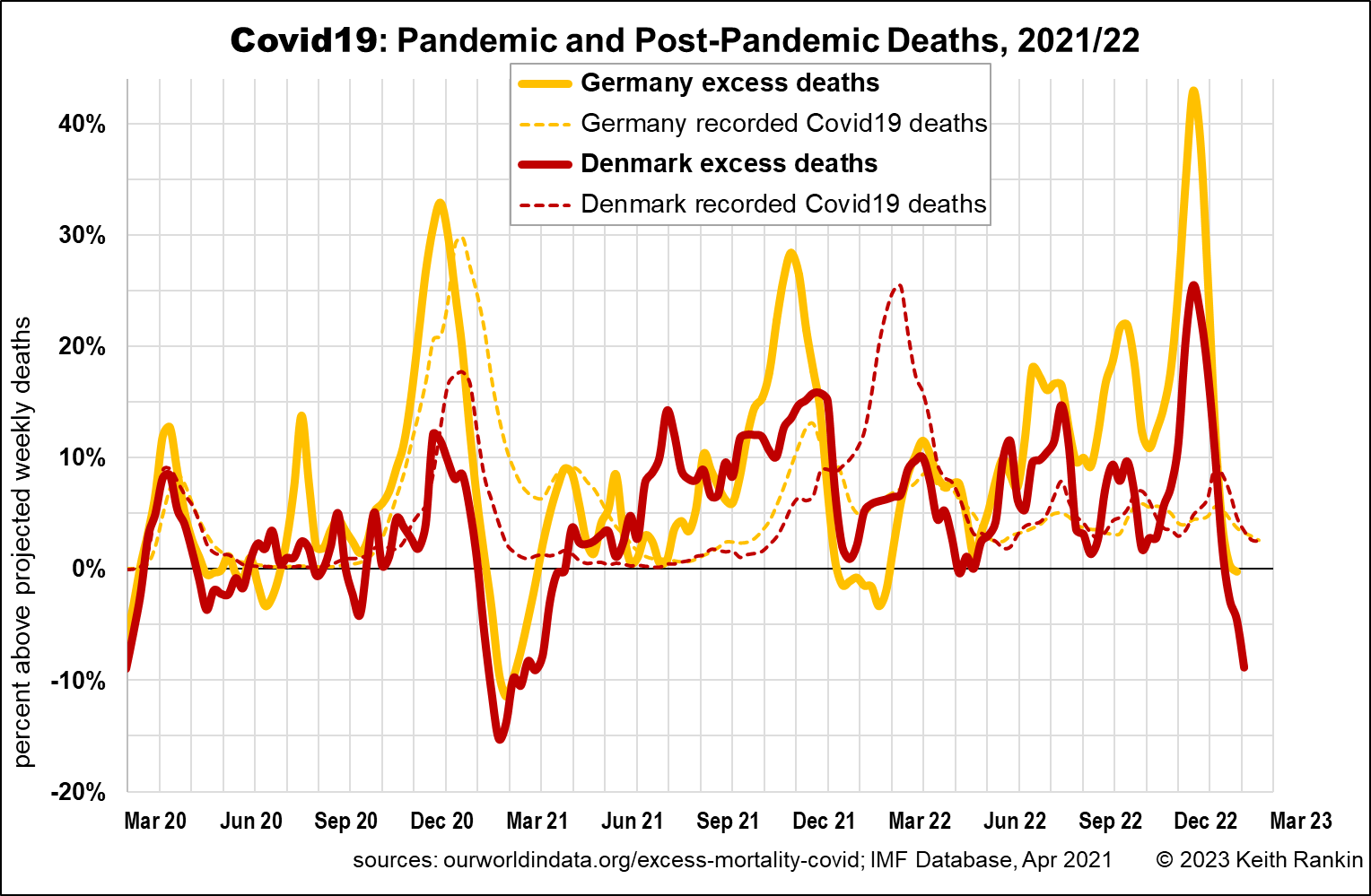

The chart above is quite alarming, and not only because of Germany’s high death toll. It’s the difference between reported Covid19 deaths and excess deaths, in the context where four waves of excess deaths in Germany in 2022 are clearly ‘epidemic’ in nature. And we see the same death waves in Germany’s northern neighbour, Denmark.

Both countries are assiduous in releasing their demographic data on deaths; most countries are not. And both countries had a reputation for having among the best sets of public health data re the Covid19 pandemic. Yet while public health data may be released with much media fanfare, demographic data usually is not. While certain public health data might be classed as ‘black verse’ poetry, and hence of interest to mainstream media, the more prosaic data sourced from ‘births, deaths and marriages’ tends to be overlooked.

In both countries, easily the worst month for epidemic deaths this decade has been December 2022. Yes, 2022, not 2020. In both countries, the people would seem to be largely unaware of this collective death experience. (Awareness would largely be confined to people’s own families.)

The widely endorsed supposition is that the pandemic is over; a concept that may mean different things to different people. To an epidemiologist, an ended pandemic may be followed by a new era with a new normal of permanently higher death rates. To the lay public, or to the pollyanna-ish finance industry which never stops telling us that we are all going to live longer, an ended pandemic means a return to something like pre-covid normality.

I watch DW (Deutsche Welle) world news semi-regularly, and I have heard nothing about the December death spike in Germany. The few stories on DW that I have found in a search today are these:

Winter illnesses burden Germany’s intensive care units, 17 Dec 2022.

Top German virologist says COVID-19 pandemic is over, 26 Dec 2022.

Germany’s new COVID debate [about removing Covid19 restrictions], 29 Dec 2022.

Are Germany’s hospitals in critical condition?, 5 Jan 2023.

WHO discusses end of COVID-19 emergency status [mainly a reference to China], 27 Jan 2023

So, as in New Zealand, there’s acknowledgement of overstretched hospitals and seasonal illnesses. There’s little suggestion that the main culprit is another covid wave, and we certainly have no indication that Covid19 has recently become more virulent.

We should also note that excess deaths in Europe have looked quite dramatic, since 2020, each December. This is because ‘normal’ influenza outbreak deaths – in the 2010s at least – tended to peak in February, not December. The big falloff in excess deaths from January 2023 is to some extent due to death numbers needing to be higher to be classed as ‘excess’.

Both countries started to downplay their reporting of Covid19 deaths from mid-2021; with the exception of Denmark during the first ‘Omicron wave’ of early 2022. We can see that, in February and March 2022, many people in Denmark died of or with Covid19, while significantly fewer people died of other causes. (This substitution of death-causes was much less true for Germany.)

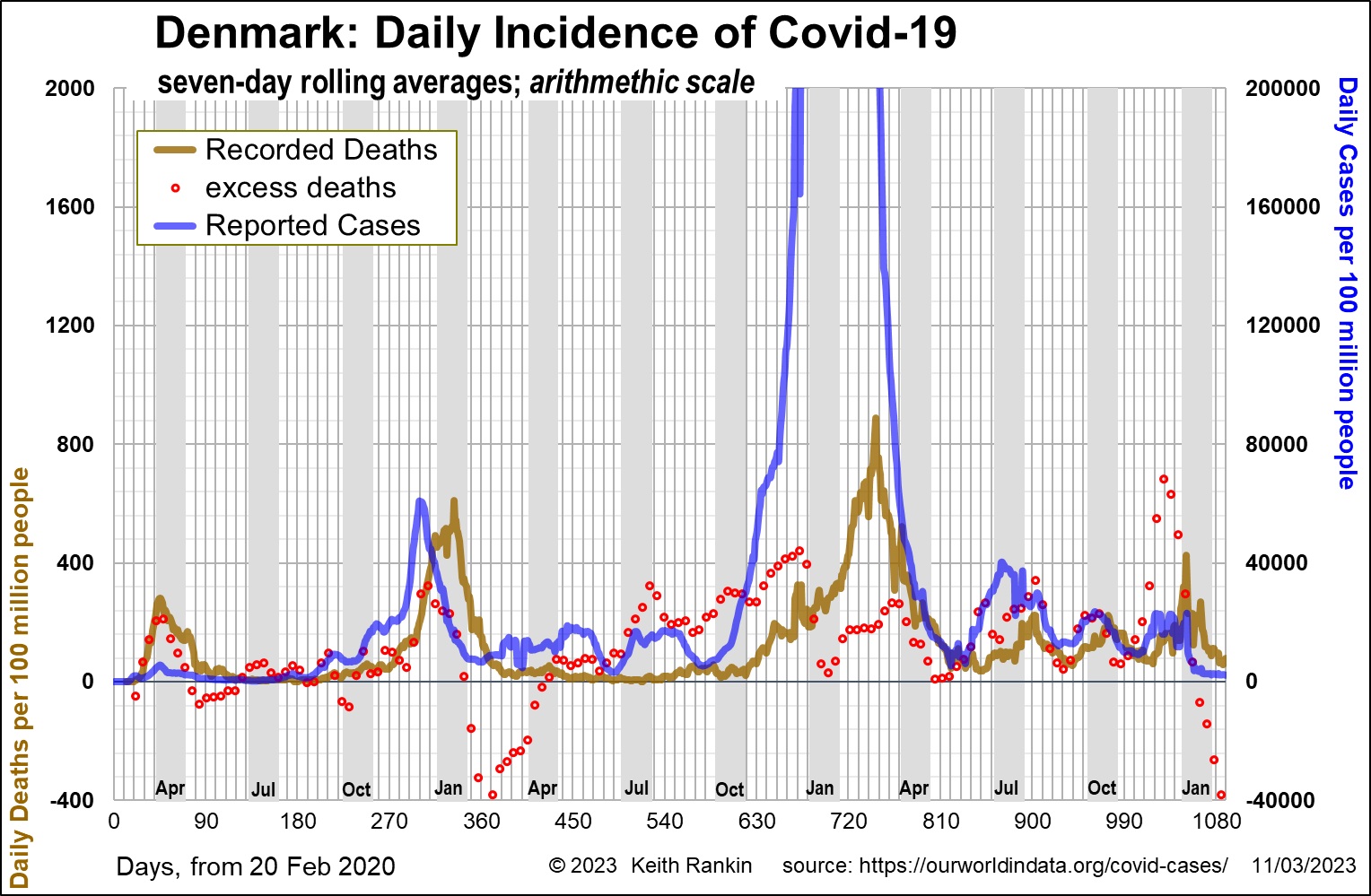

But the situation in Denmark reversed in December 2022, with many more excess deaths than reported Covid19 deaths. Indeed, in Denmark there were five death waves in 2022, and all (except perhaps the relatively small June death wave) correlating with reported Covid deaths (but see the Denmark chart below); expect that the peaks in reported deaths have been increasingly lagging the actual death peaks. The Denmark data in this chart definitely points to all of these death peaks as being associated with recurring waves of Covid19.

We certainly see the same lags in the German data, although the reported death waves are less pronounced. Generally the ‘peaky’ nature of the data suggests that these populations have been facing repeated outbreaks of respiratory viruses; outbreaks for which their immunity levels have been decreasingly able to cope. While waning immunity appears to be the main problem – a problem long known in relation to human coronaviruses – and that waning immunity here likely relates in particular to vaccination immunity, it is also possible that each wave of infection creates new morbidities in the most vulnerable people. So, a combination of waning immunity – covid immunity and general immunity – combined with new comorbidities is leading to progressively higher death tolls. We also note that December in particular is a month characterised by much social ‘mixing and mingling’; conditions ripe for coronaviruses transitioning from epidemic to endemic.

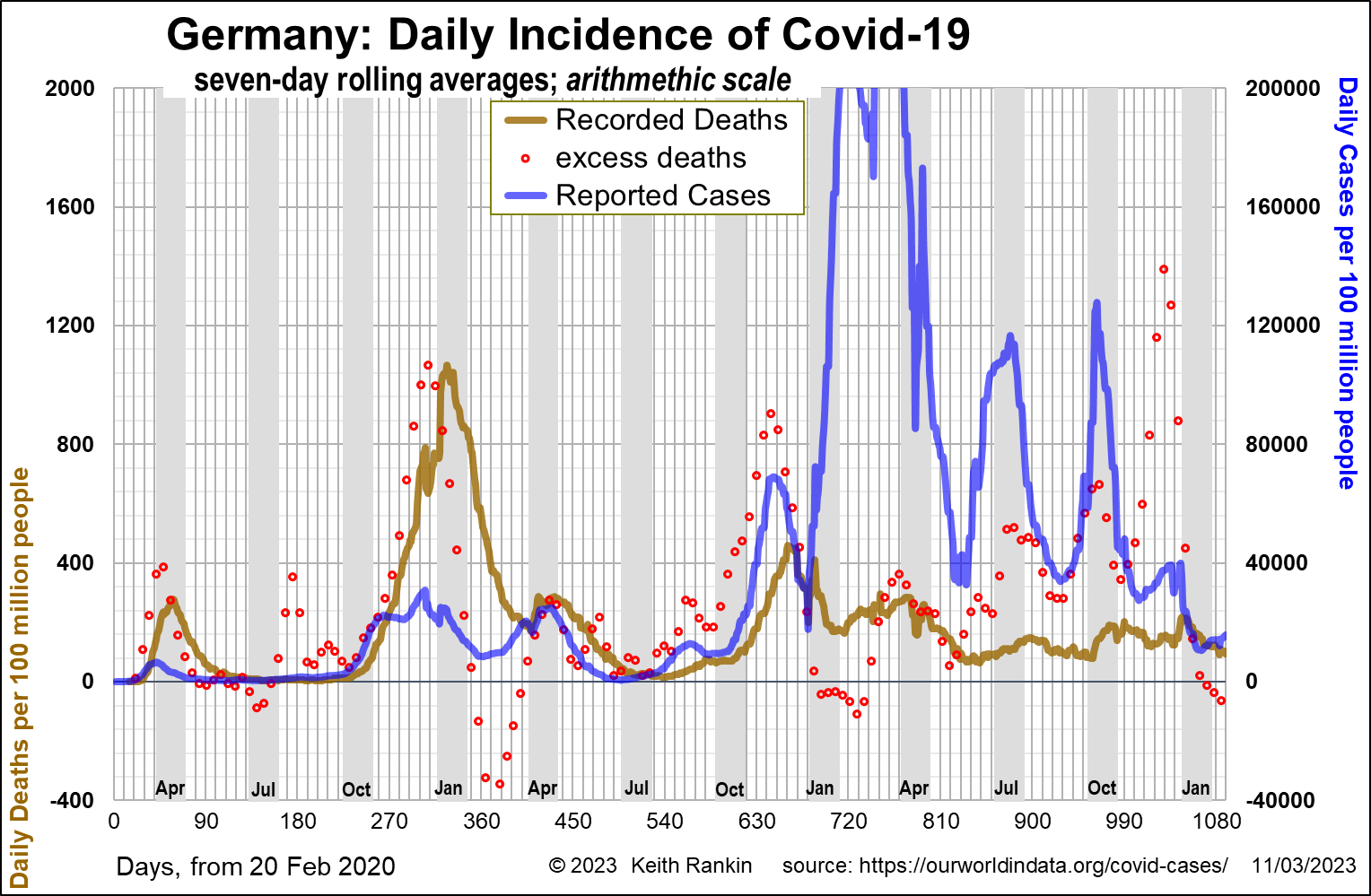

These two charts, for each country separately, also include ‘case’ information. Again, while underreporting is also an increasing feature of case data, this is data that underpins the timing of Covid19 outbreaks (as distinct from non-covid respiratory viruses). Nevertheless, case data may also lag actual deaths, as people are slow to test for covid, and report, until they are fully aware that a new outbreak is taking place.

When we look at Germany, we can clearly see the correlation of case data (in blue) with excess deaths (in red). When there were new covid variants, as in March 2021, August 2021, and January 2022, we can see the uptick in reported cases leading the uptick in deaths. Otherwise, we tend to see the uptick in deaths coming first, with case reporting lagging ever-further behind. December 2022 was particularly striking, with an eventual upsurge in cases suggesting that a significant number of people who died in the death spike were indeed infected with the coronavirus. In Denmark the pattern of excess deaths correlating with reported cases of Covid19 is, if anything, even stronger.

If we think of Covid19 as a three-year pandemic, we can see that in both countries the second half of the pandemic was worse than the first half, regardless of the official cause of death attributed to each casualty.

A death is a death is a death. To dying persons, and their families, it matters little if a death is directly or indirectly caused by Covid19. An indirect death may be due to a loss of general immunity, or to any other factor linked either to the biology of the virus, to fear-induced behaviour changes arising from the attention given to the virus when it was a big story, or to the government mandates ‘to keep us safe’ but which may have (to some extent) substituted one risk for another.

*******

Keith Rankin (keith at rankin dot nz), trained as an economic historian, is a retired lecturer in Economics and Statistics. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand.