Analysis by Keith Rankin.

The charts below are all to the same scale. Strictly speaking, they show seasonal mortality rather than excess mortality. The zero percent baseline represents low-season mortality rather than average mortality.

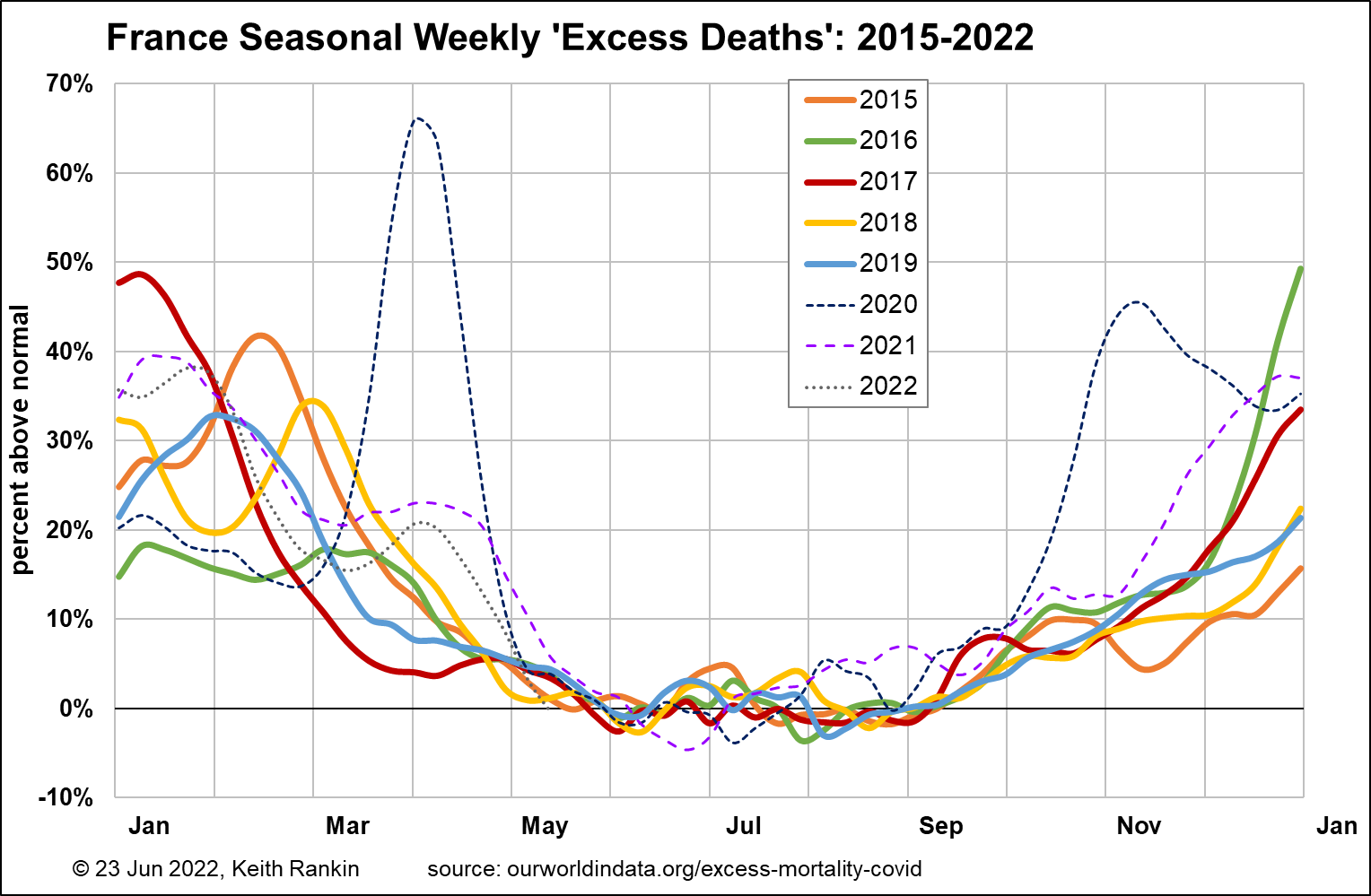

France

French mortality data shows a big covid ‘spike’ in March 2020, and a late-2020 autumn ‘second wave’. Only the first of these is unusually high, in comparison with normal seasonal epidemic peaks. However, the 2020/21 wave was unusually prolonged. In addition, we see an earlier than usual mortality seasonal wave in 2021/22; this was France’s ‘delta wave’ which peaked in December and January.

We know that French people had high levels of exposure to Covid19, regardless of public health measures taken. This is because France still has a global empire, and because French people holidaying in French overseas territories caused high levels of covid mortality in there (especially in the Caribbean). Despite these high levels of exposure, it is clear that mortality rates in France are now substantially in line with normal seasonal patterns, and are likely to remain so. The pandemic appears to be over in France.

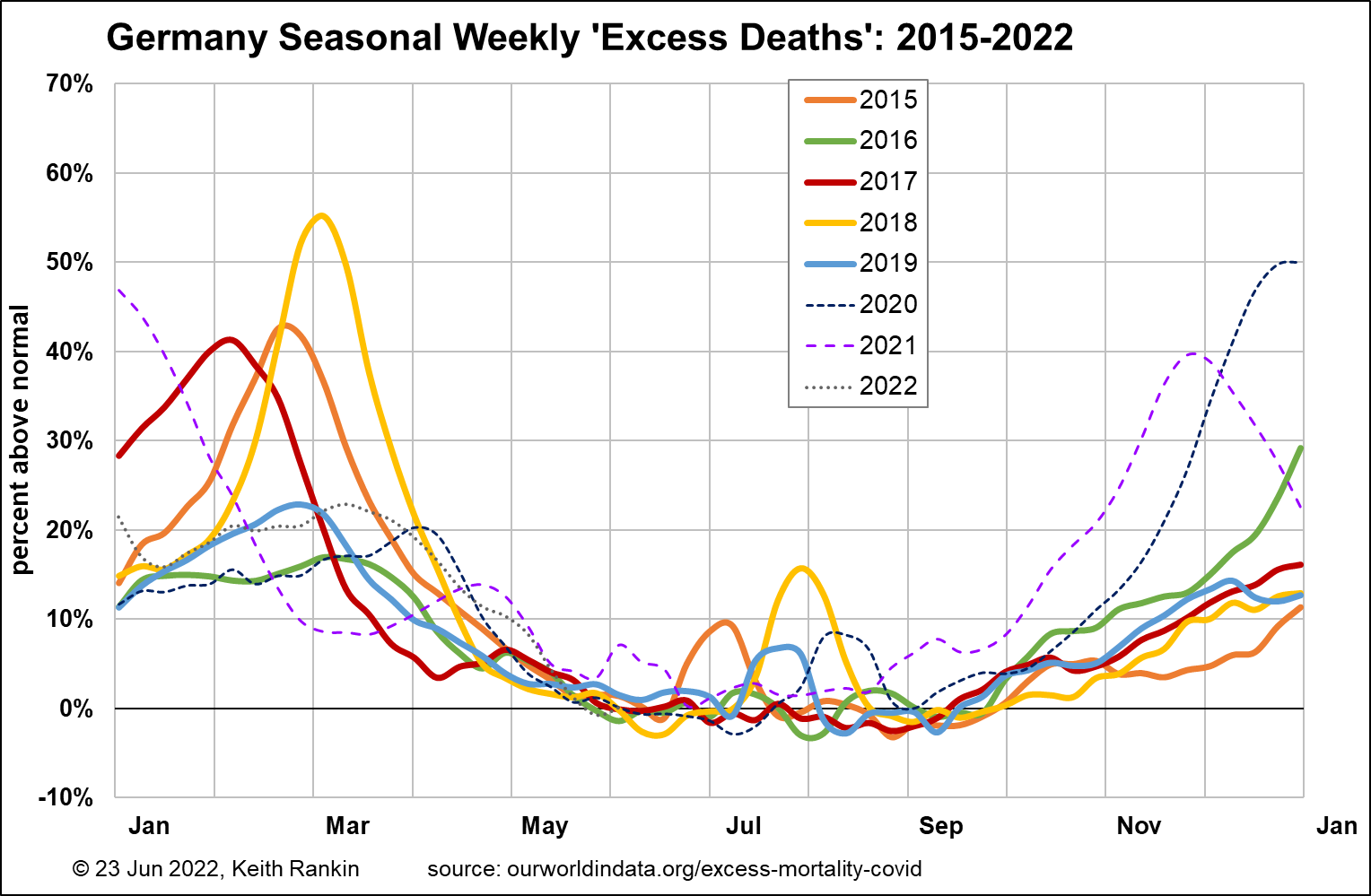

Germany

Germany got its public health measures in place in time, just; that is, compared to France. As a result, seasonal mortality in Germany in early 2020 was less than usual; it had no influenza season to speak of in 2019/20. (Germany is also interesting for its summer mortality mini-peaks. Because the timings vary, we can be sure that these are travel-induced mini-epidemics.)

Germany had a higher mortality peak in the 2020/21 winter, though slightly shorter than France’s. As with France, these deaths were mostly due to Covid19 infections. A year later, in 2021/22, Germany had more severe epidemic mortality than did France. Germans appear to have been significantly less immune to covid and other respiratory viruses in France last autumn and winter.

Peak seasonal mortality in Germany remains its 2018 influenza outbreak, part of an influenza pandemic which raged from late 2016 until March 2018. (Note that the practical use of the word ‘pandemic’ should not be constrained by the declarations of the World Health Organisation bureaucracy; pandemics are more apparent in historical context than within the periods they are lived through, and bureaucrats are fickle in what they emphasise.)

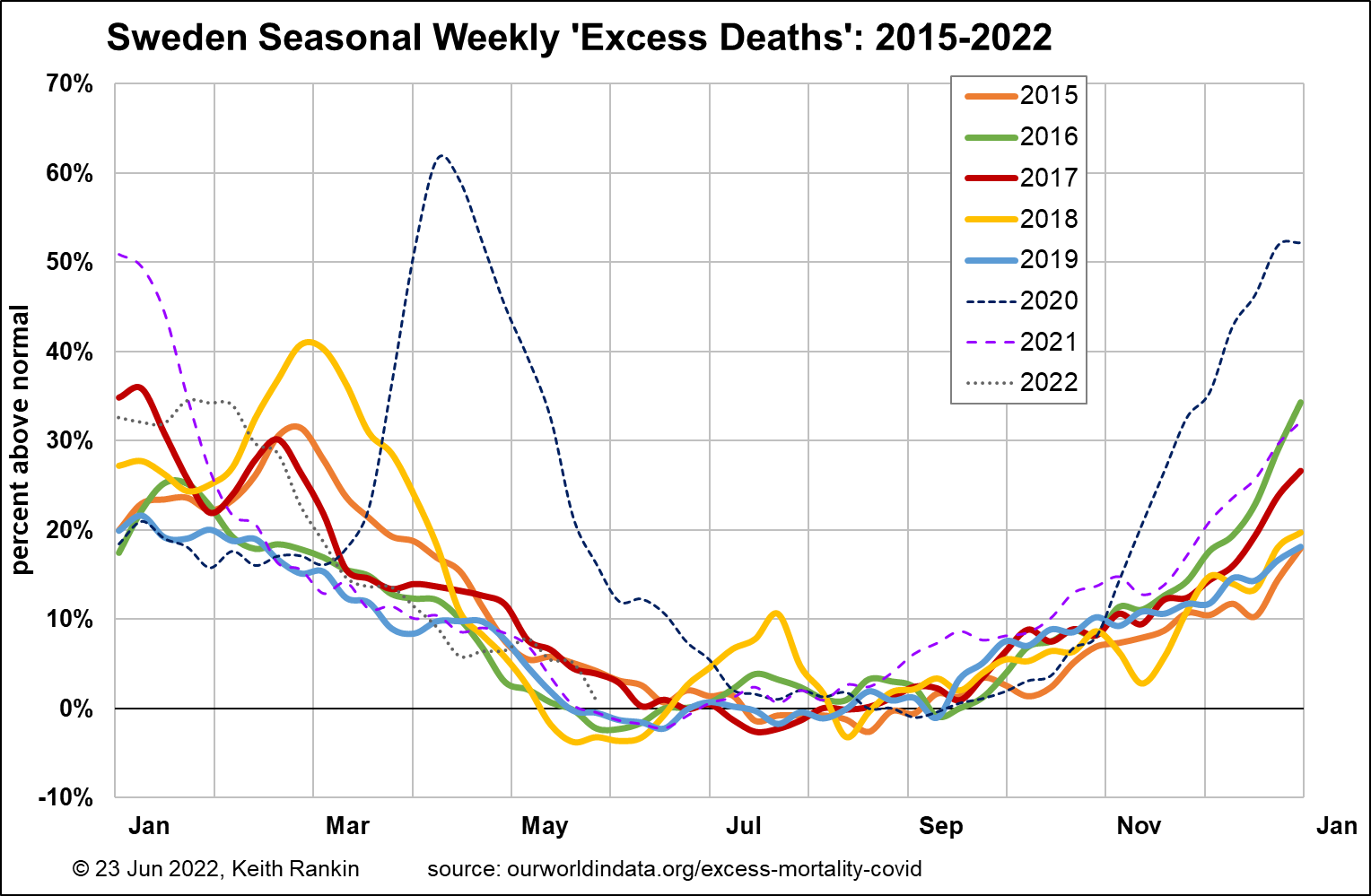

Sweden

Sweden gives a picture of what Germany’s experience of seasonal mortality would have been had Germany taken a largely hands-off public health policy stance. Sweden and Germany have much in common in their economies and demography. (The main differences are that Sweden has more older people, having been neutral during World War Two, and also that Sweden has more opportunities than Germany for natural physical distancing.)

Sweden got the big mortality spike in the spring of 2020, later and longer than France. This was mainly people aged over 80, of which Germany had relatively few. Also, Sweden, even more than Germany, had had no real experience of influenza since early 2018; so Sweden had many older people who would have already died had there been normal seasonal influenza in 2018/19 and 2019/20. Sweden went on to have a similar experience of seasonal illness – mainly ‘gumboot’ (ie pre-variant) Covid19 – as Germany in 2020/21.

What is particularly interesting for Sweden is its relative lack of excess mortality in the latter part of 2021 – more like France than Germany – during the global ‘delta wave’ which represents the global peak of the pandemic. Mortality data does suggest that Sweden did indeed reach a state akin to ‘herd immunity’; Sweden had perhaps the least stringent anti-covid public health measures in the world.

The general response of public health professionals in New Zealand and many other countries towards Sweden’s superior 2021 performance has been to ignore it. This, more than anything, shows that a large proportion of what we hear in New Zealand is narrative, not disinterested science.

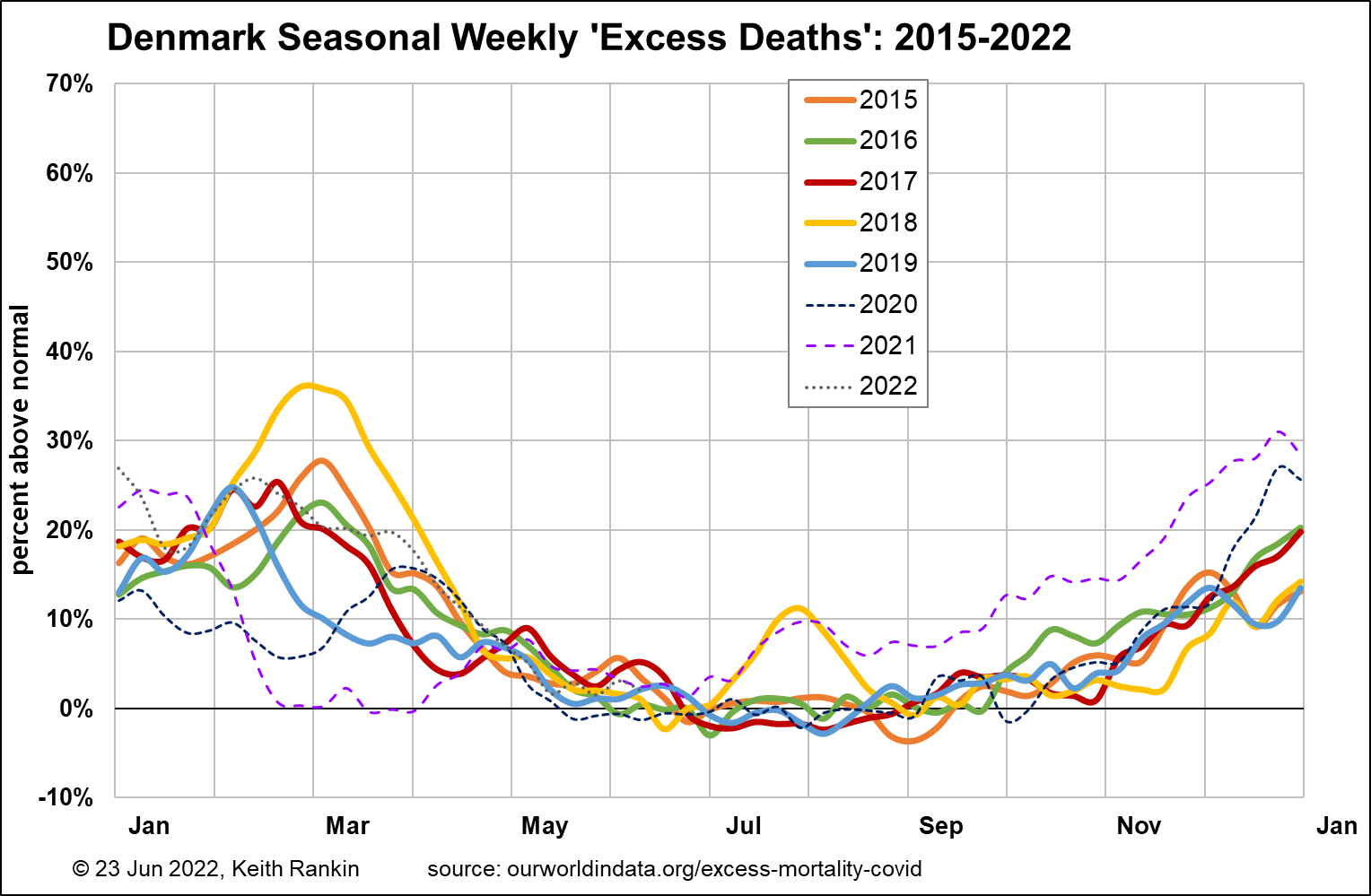

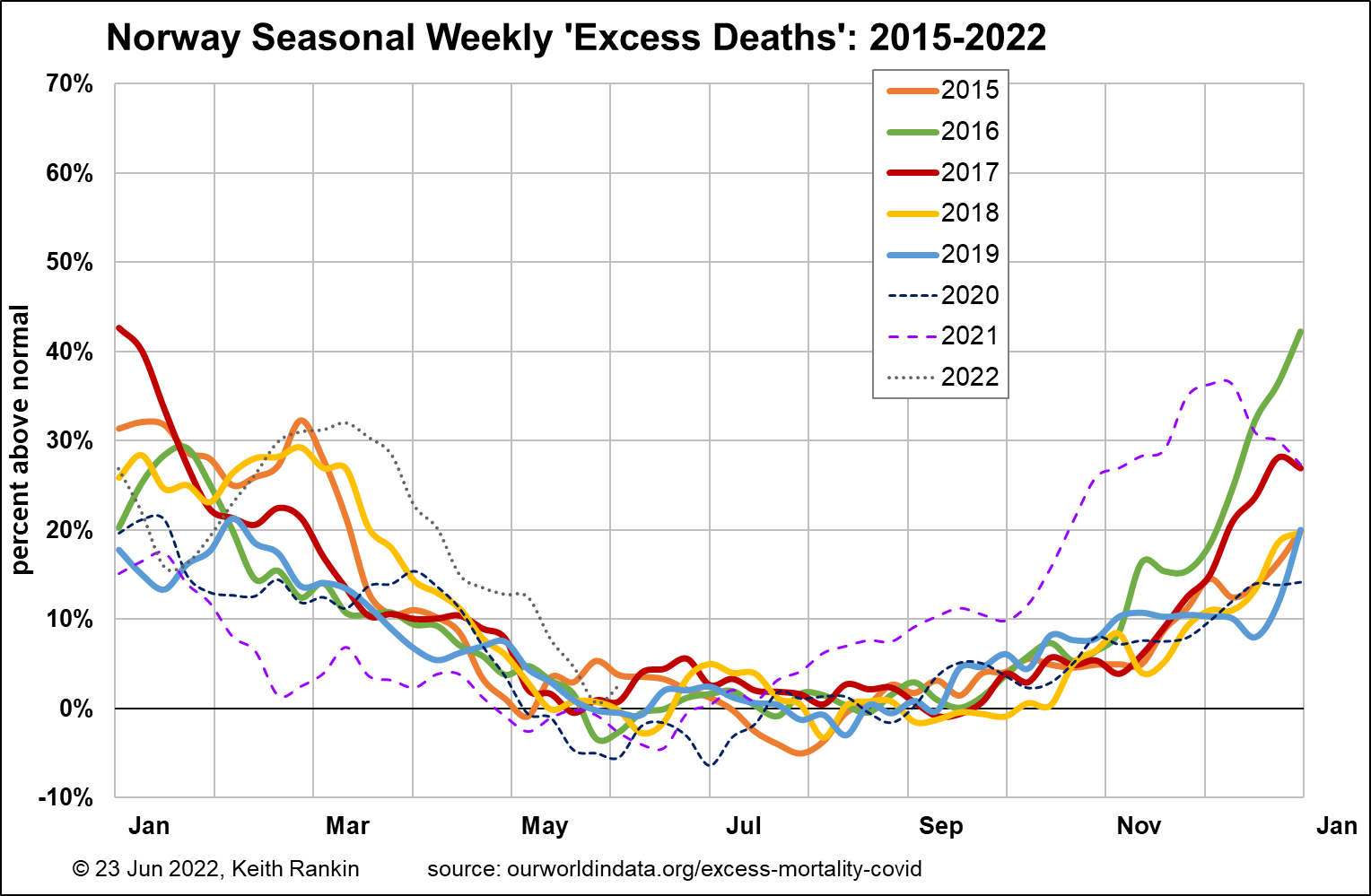

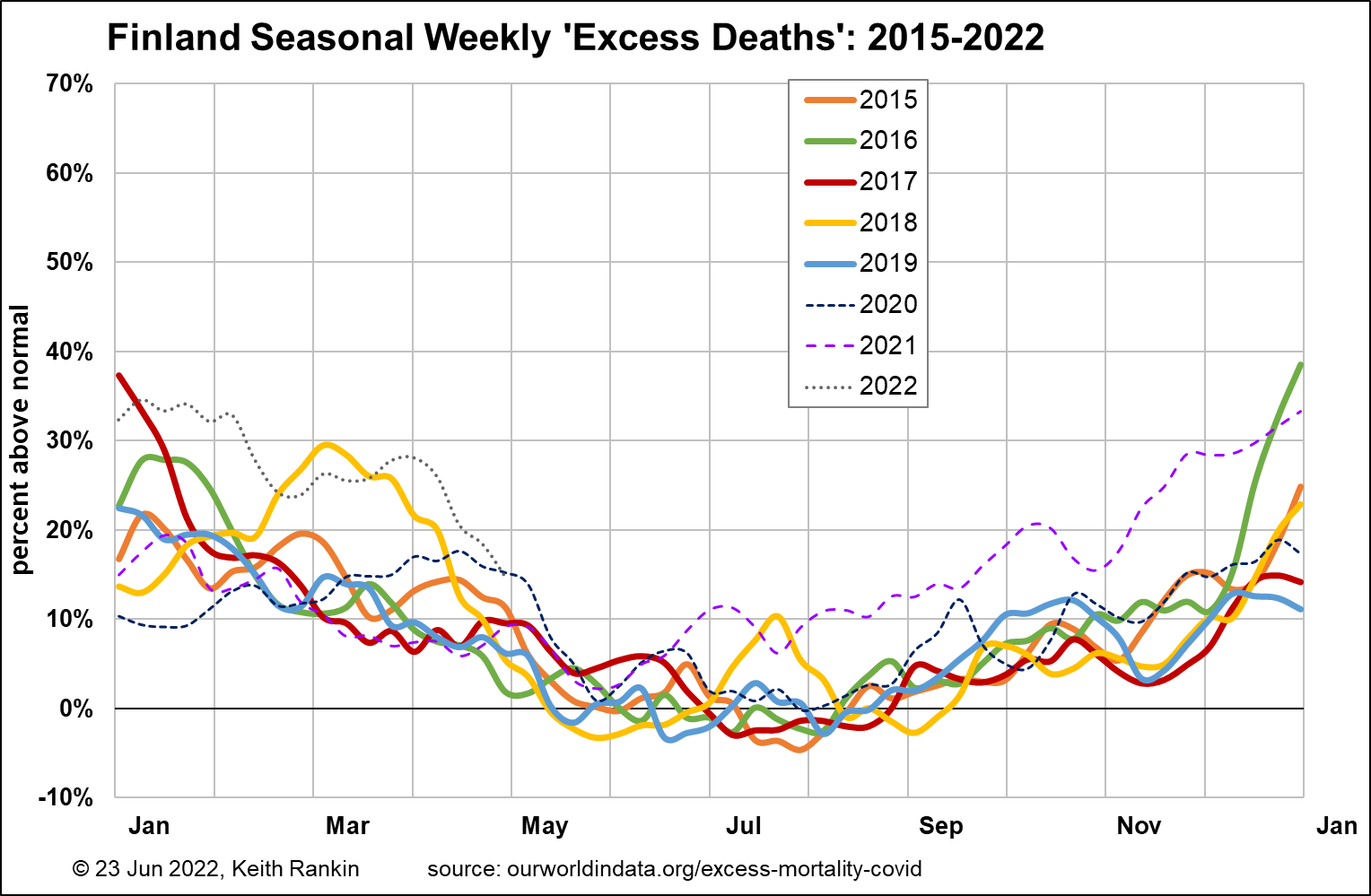

Denmark, Norway and Finland

The other Nordic countries pursued public health policies similar to Germany – and dissimilar from Sweden. While these policies protected their populations in 2020, the story in 2021 and 2022 has been problematic.

Denmark has a clear pattern of excess mortality in the latter half of 2021, suggesting an immunity weakness in its population comparable with Germany; an immunity weakness apparent in neither Sweden nor France. Sweden and France were the best prepared countries for the ‘delta wave’ of Covid19.

Norway shows a similar pattern to Denmark after mid-2021; a pattern of excess mortality which has continued well into 2022. Finland repeats this pattern of Norway.

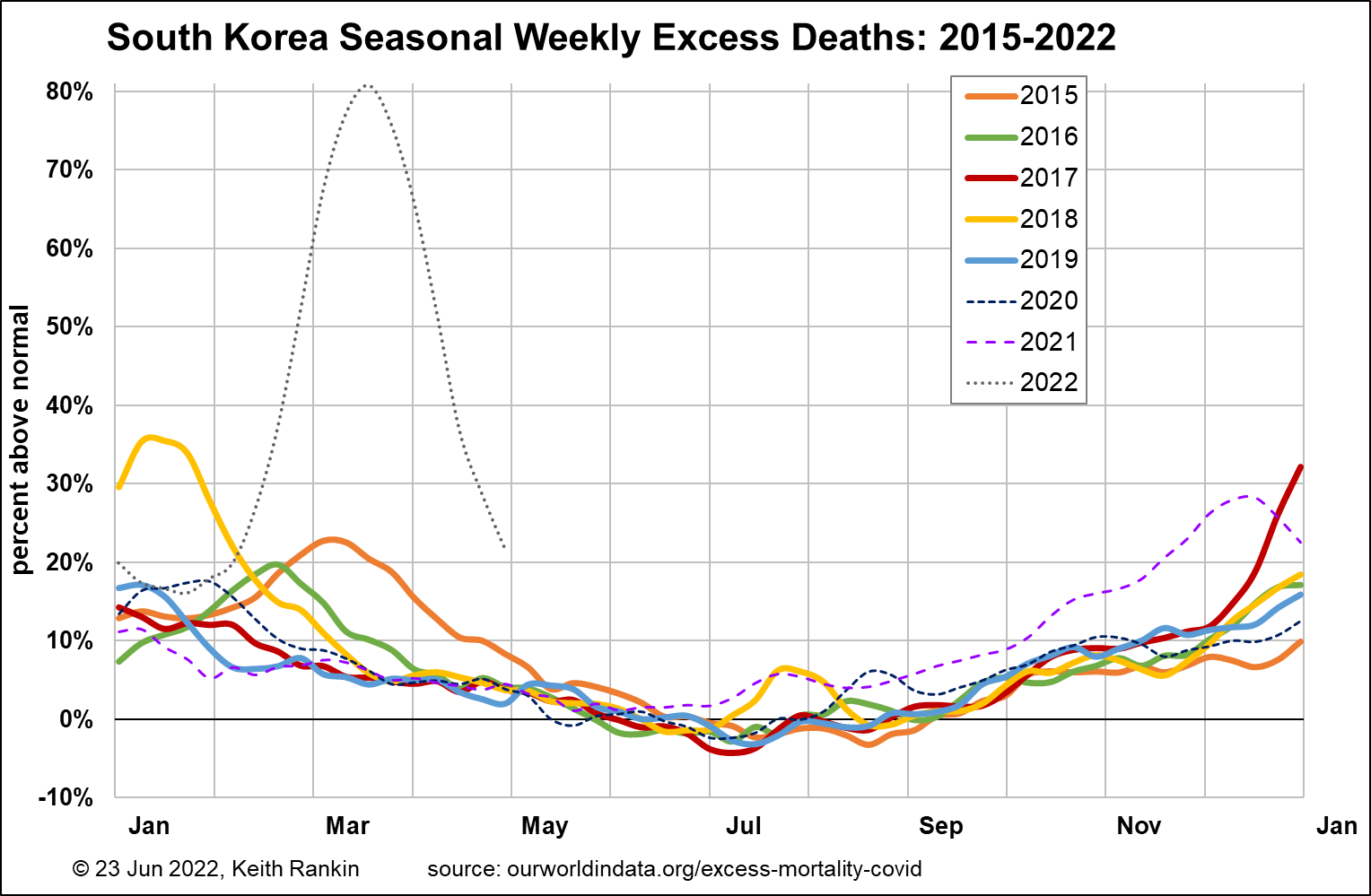

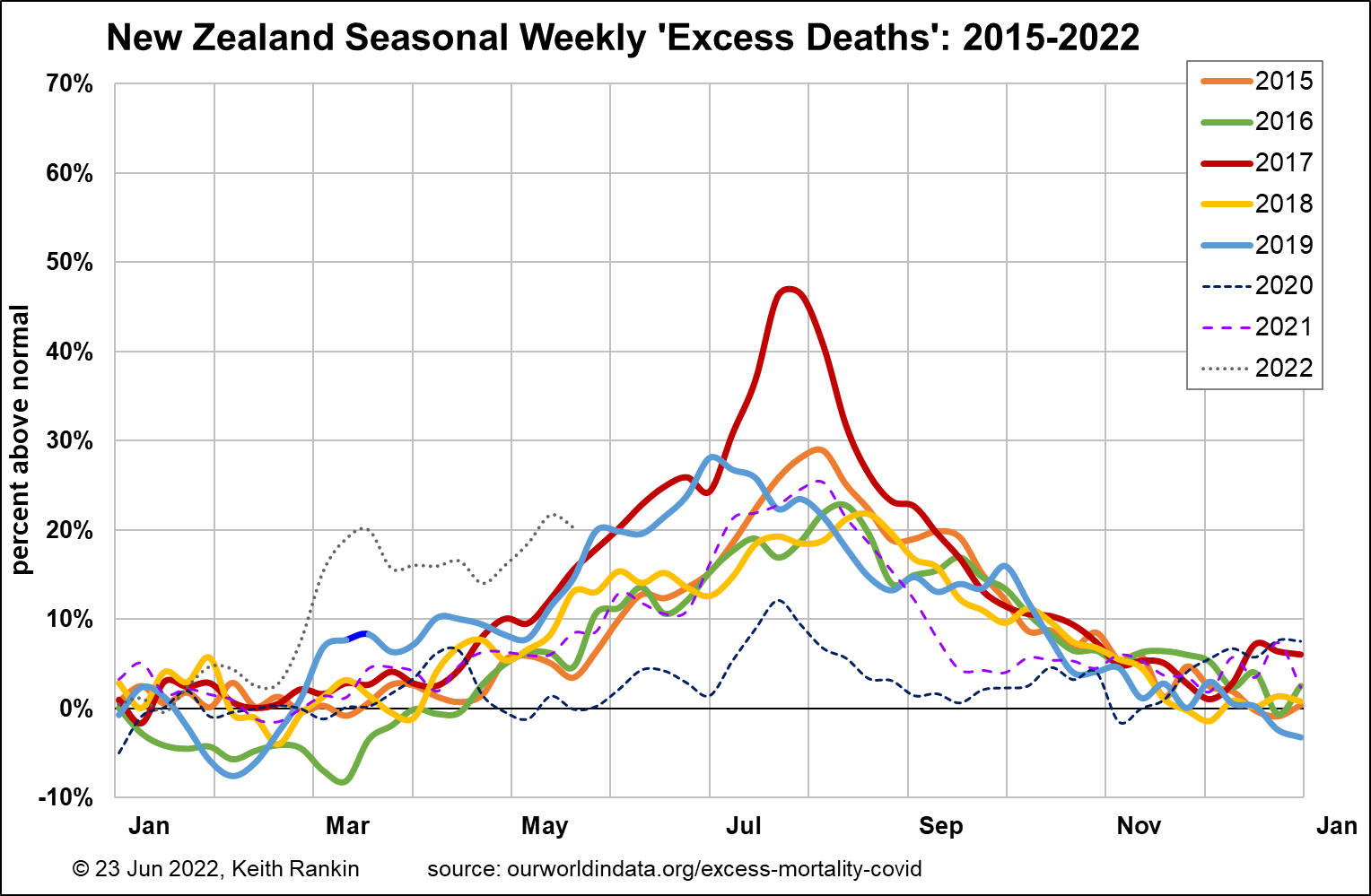

South Korea and New Zealand

As well as experiencing excess mortality in late 2021 similar to these Nordic countries, South Korea experienced a huge covid mortality spike in March this year.

New Zealand suffered from the late 2016 to early 2018 influenza as badly as any other temperate country. With influenza back in New Zealand in 2022, and as countries like Taiwan, South Korea and New Zealand – ie countries which pursued among the most vigorous policies to keep covid out – have been experiencing substantial recent waves of covid mortality, New Zealand is likely to easily exceed its 2017 seasonal mortality peak.

My hunch, based on what we are hearing already about covid and influenza in New Zealand – and based on the experiences of immunity-compromised populations in the northern hemisphere – is that seasonal mortality in New Zealand will peak this August at around (or above) 70 percent above summer ‘normal’ death rates.

*******

Keith Rankin (keith at rankin dot nz), trained as an economic historian, is a retired lecturer in Economics and Statistics. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand.