Analysis by Keith Rankin.

These five charts look at five countries for which excess death information is available. First, it is important to note that I am presenting a different definition of excess deaths than other sources, in that these charts include seasonal excess deaths arising from triggers other than Covid19.

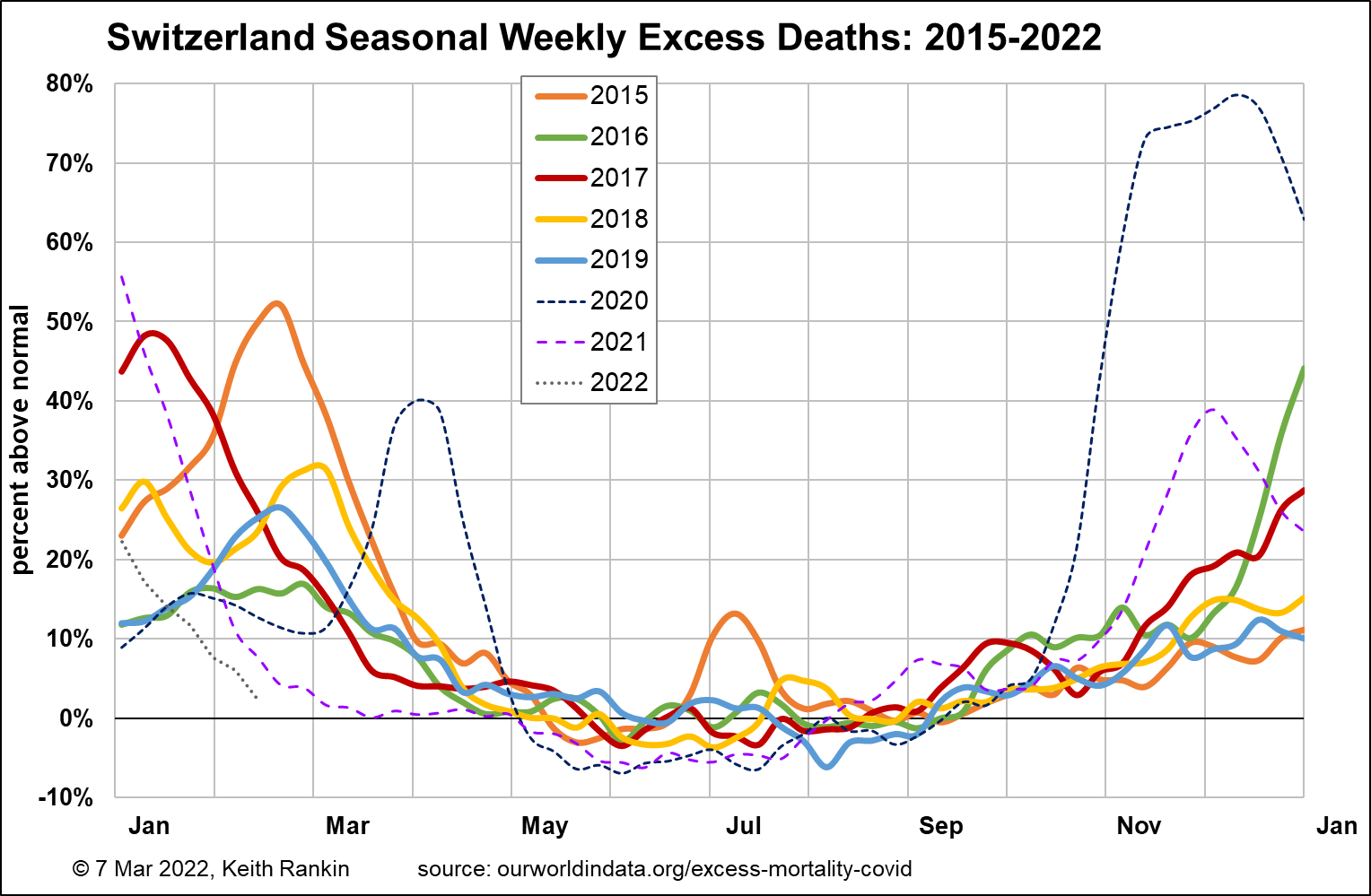

Switzerland, the Optimistic Note

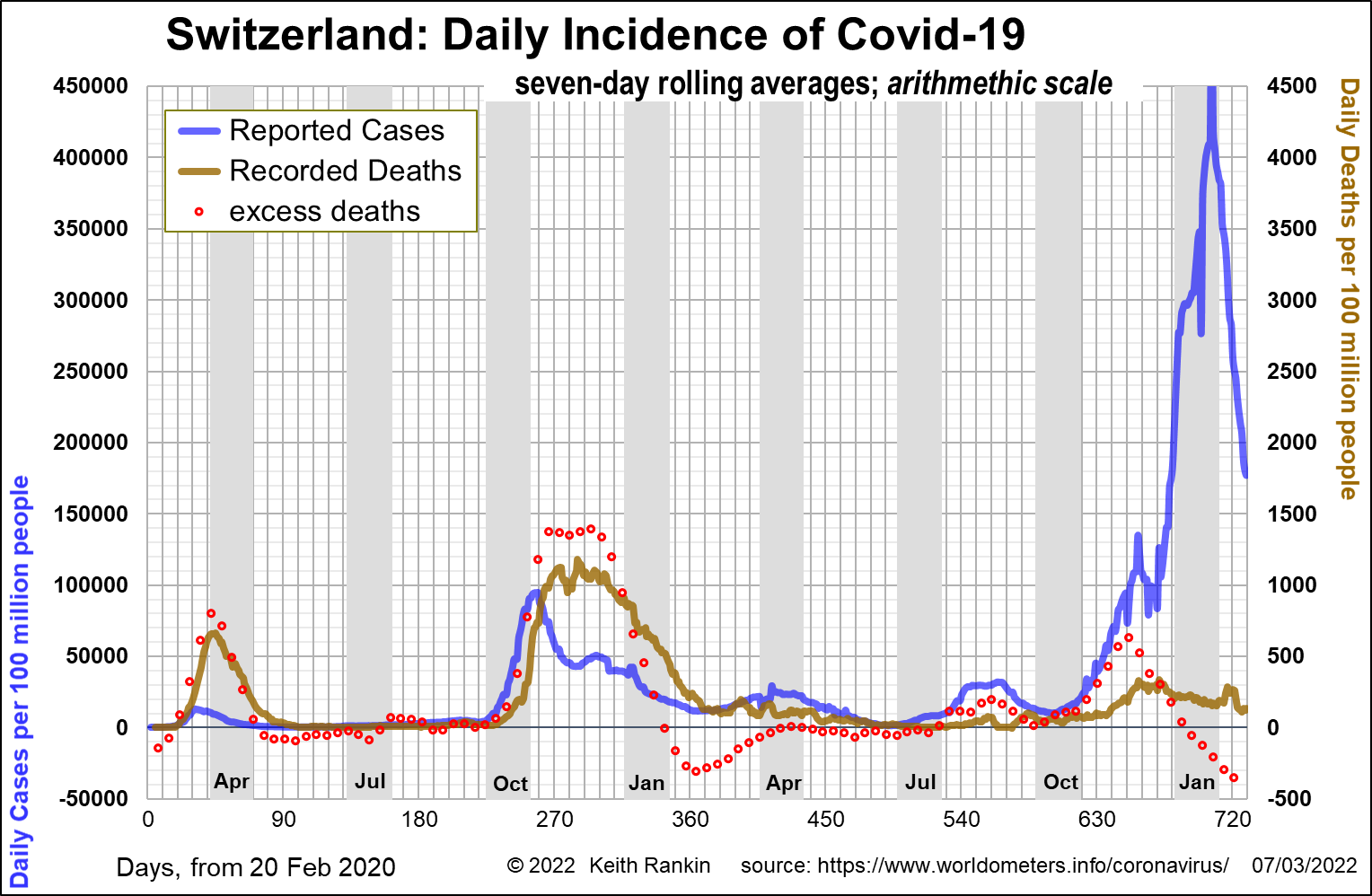

Switzerland had a significant outbreak of Covid19 in March 2020, and it fully experienced the 2020 late autumn outbreak that featured across Europe. 2020 was easily Switzerland’s worst year, and it took place without variant-strains of covid, and before vaccinations. We can see from the summer 2020 data that Switzerland did take public health measures against covid; death rates were unusually low in both the summers of 2020 and 2021.

Switzerland’s third outbreak was the Delta outbreak of August 2021, clearly visible in the chart. More clearly visible is the second Delta outbreak in November 2021; an outbreak that once again (in late autumn) affected all of Europe, and that was clearly linked to waning artificial (vaccination) and natural immunity.

Omicron arrived in Switzerland in December, just as the Delta wave was waning. There is a very good chance that omicron-covid was an important factor in limiting Switzerland’s second delta outbreak. Indeed, as omicron engulfed Switzerland in January 2022 (second chart), covid deaths continued to plummet.

In Switzerland’s case, Omicron seems to have had a protective impact on a population with relatively few problems with immunity or comorbidity. This protective effect is unlikely to be the case in New Zealand, however, this winter. Before we leave Switzerland it is important to note the importance of October and November in that country. For Aotearoa New Zealand, that translates to April and May.

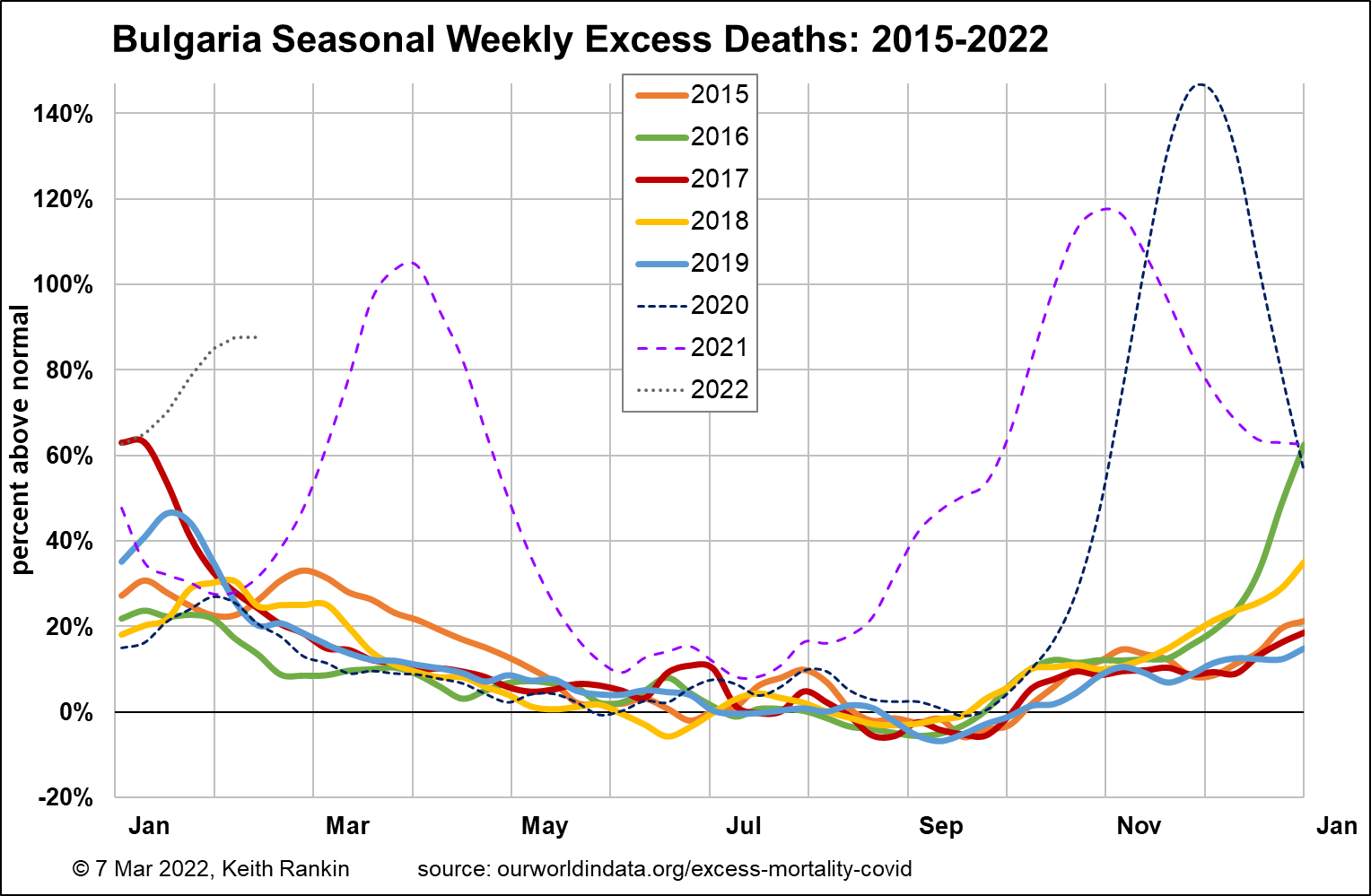

Bulgaria

Bulgaria’s situation is ugly. Unlike Switzerland, Bulgaria is in the European Union, though it’s hardly a typical European Union country. As a Black Sea nation 200km from Ukraine, Bulgaria will now be suffering the aggravating impact of the war. Its population is not much bigger than New Zealand’s. It has excess pandemic deaths of 69,000; almost exactly one percent of its population, and incurred just in the last 16 months.

Bulgaria was initially one of the most successful countries – if not the most successful – at keeping covid out. There was a typical bout of seasonal influenza early in 2020, and that may have helped to keep covid at bay for so long. And Bulgaria did take a similar range of public health measures as other European countries, during the 2020 first European wave of covid. (For comments on the ways that one virus may protect populations from another, refer Flu season could follow hard on the heels of Omicron, Dr Richard Webby interviewed on RNZ.)

Bulgaria, with its older population than most – due to inter-European emigration – Bulgarians were particularly vulnerable to the lethal November wave of the original (Wuhan) covid variant. Subsequently, Bulgaria suffered two huge waves of covid-pestilence in 2021, the second (delta) of these waves compounded by governmental distrust that translated as vaccination distrust. Thus – contrary to the Swiss who were largely in the Goldilocks zone with high immunity and low comorbidity – Bulgarians found themselves with low immunity and high comorbidity.

For Bulgaria, the worst news is that omicron-covid didn’t arrive, as it did in Switzerland, as an anti-delta army of white knights. Bulgaria conspired to keep Omicron out, meaning at the end of December 86% of sequenced cases were still Delta (same as New Zealand). In the first half of January Bulgaria and New Zealand were both in the mid-fifty-percent for the percentage of Delta. And in the latter part of January, both countries were in the mid-twenty-percent range for Delta. The main differences between Bulgaria and New Zealand were that the total amount of covid in Bulgaria was greater, that vaccination rates were lower in Bulgaria, and that it was winter in Bulgaria.

At its winter low-point, Bulgaria’s covid death experience were similar to its worst recent influenza outbreak (2016/17). But then Bulgaria’s deaths took off again, mostly due to ongoing delta infections in a population made comorbid by earlier waves of delta and pre-delta covid variants.

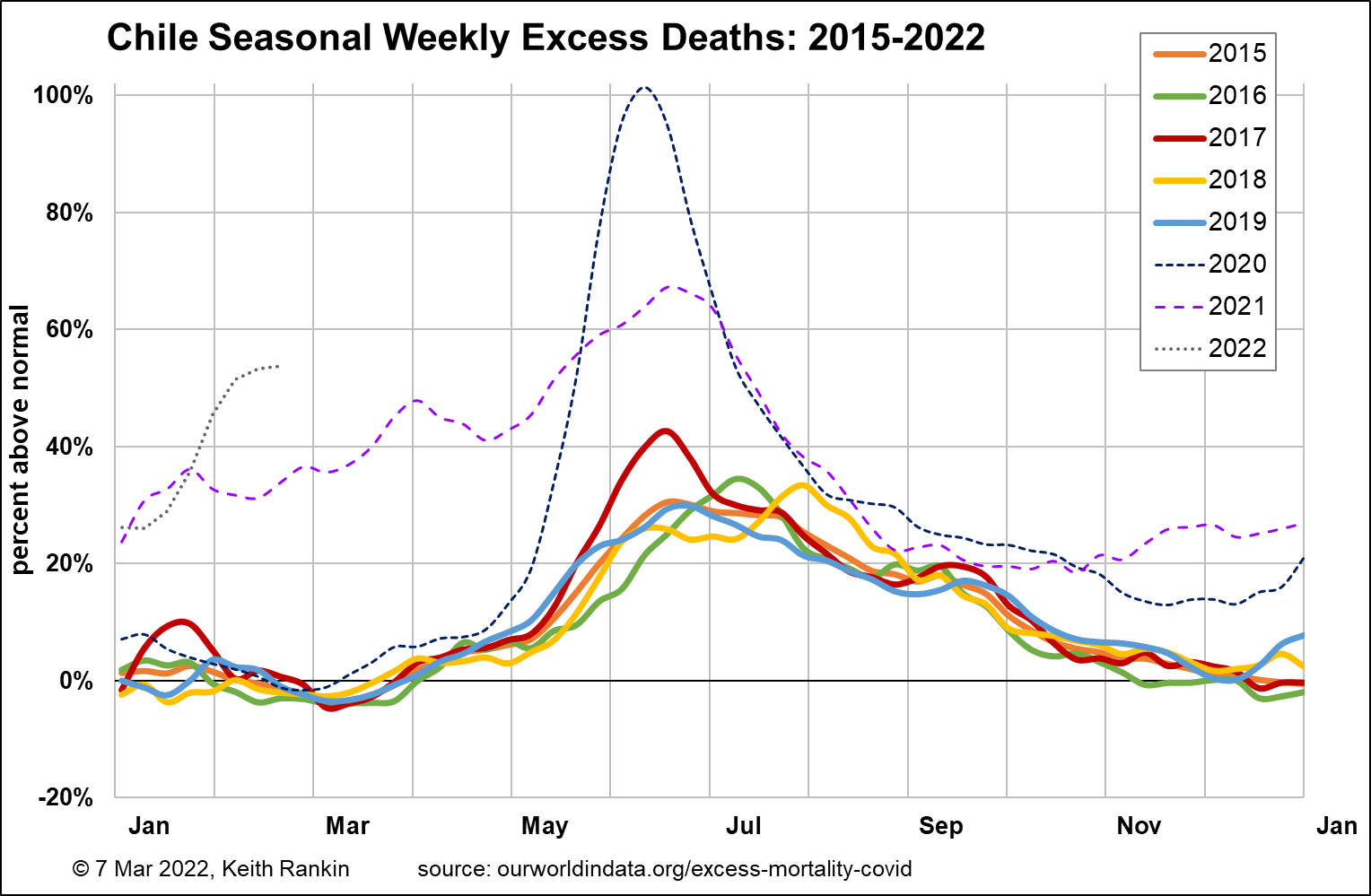

Chile

Chile, the country not unlike New Zealand – across the big (Pacific) ditch – had a typical covid death wave in its first covid winter; while it had lockdowns, clearly it did not have a New Zealand-like MIQ border protection system. (Argentina, with more stringent anti-covid measures than Chile, held out for longer than Chile, but has had an overall covid death toll at least as high as Chile.)

Sadly, Chile continued to have significant numbers of excess deaths for the remainder of the pandemic; their only months of respite were August and September 2021. Chile started a comprehensive vaccination programme well-before New Zealand. Sadly, a combination of an inferior vaccine and earlier waning immunity, copped covid heavily during its delta-summer.

Chile does represent a counterfactual for how New Zealand could have been. The important thing to note, though, is that the Covid19 pandemic – as a deadly event – is not over yet. In February, Chile did a Bulgaria. While Chile got rid of the delta-variant as omicron arrived, Chile suffered considerably over Christmas New Year from a mystery ‘other’ variant. While that variant has since quelled, a look at the Chile chart does not bode well for the coming southern hemisphere winter.

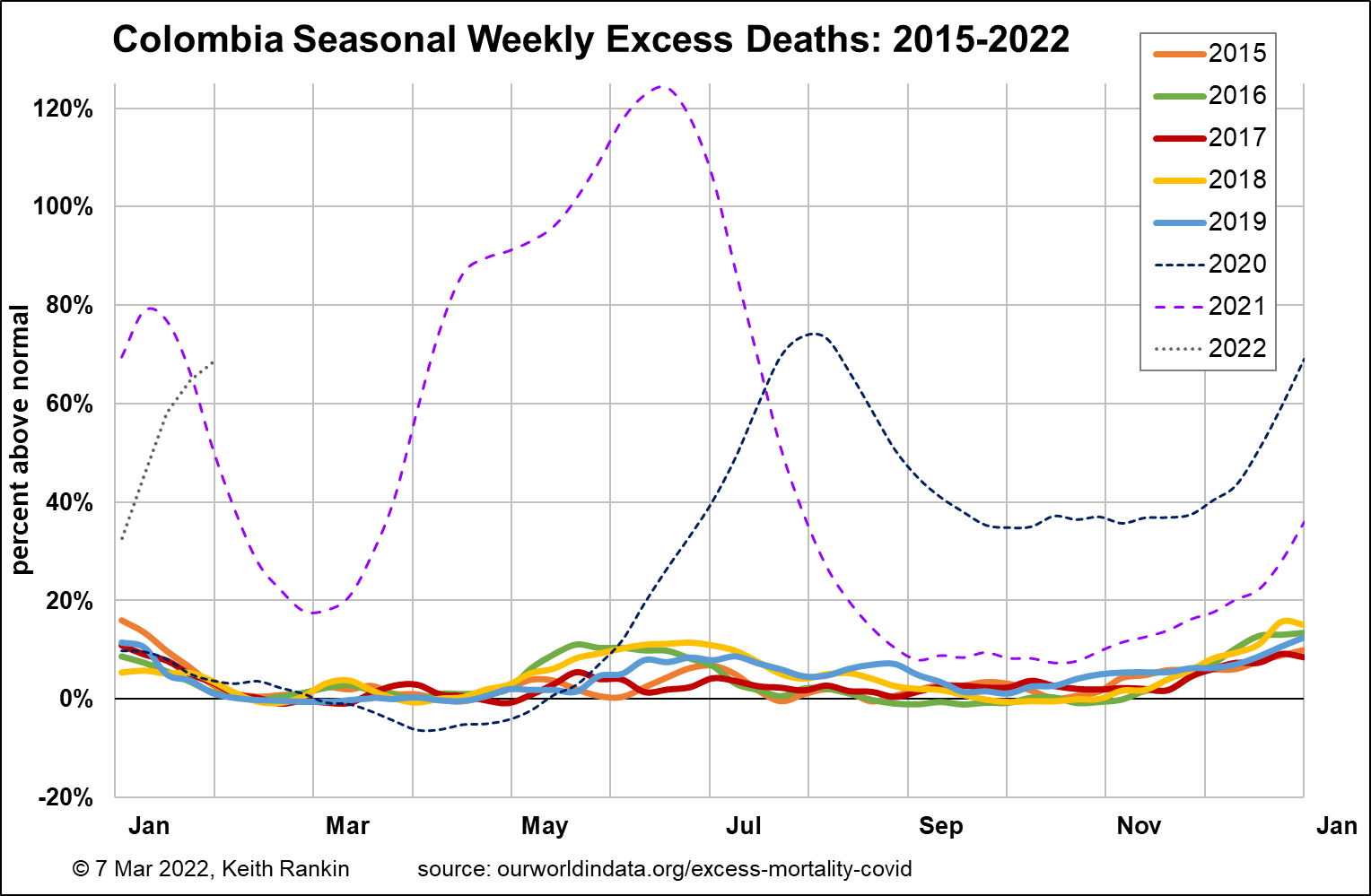

Colombia

Colombia is of particular interest as a high-life-expectancy country with a mild climate due to altitude rather than to (temperate) latitude. Like all the others mentioned above – except Switzerland – Colombia held covid out for as long as it practically could. Nevertheless, covid completely dominates the mortality footprint of that country, except for September and October.

Worryingly, like Bulgaria and Chile, covid deaths in Colombia are in incline, not decline. Also, Colombia is another Delta hold-out, with delta-covid slightly increasing its ‘variant-share’ in late January (the latest available data for that country).

Colombia may be a good example of a country that is less-protected by seasonal viruses (because it does not have seasons, as we in temperate countries understand seasons) from the most dangerous viruses. (Refer again to Dr Richard Webby, who understands better than most ‘experts’ the place of viruses in the ecological regulation of populations.)

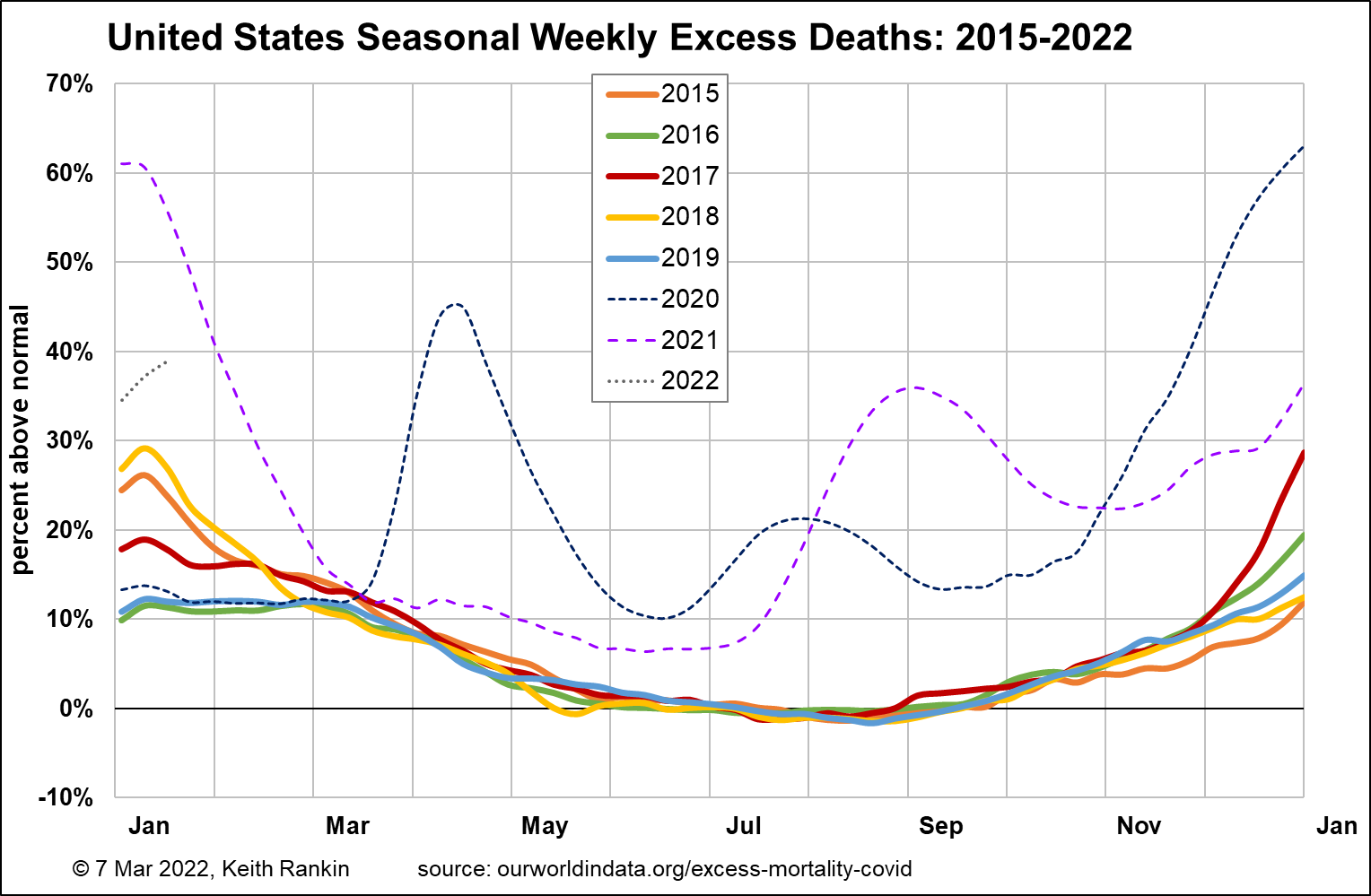

United States of America

Finally, the United States. Let’s just say that it looks like an average of the previous three. Indeed, the United States has a higher all-pandemic covid death toll than does Chile. Inequalities (which generate comorbidities, and distrust of governments) – and historical life expectancy – make the United States, demographically, more like South American and Eastern European countries than like high-GDP western European countries.

New Zealand

So far, New Zealand has no excess deaths due to the covid pandemic. Indeed it has negative excess deaths from Covid19.

However it is still far too early to say how New Zealand eventually will compare, say by 2025, with these countries (and with those other countries New Zealanders more readily compare themselves with). The war in Ukraine will of course have global impacts on mortality which will complicate any future statistical analysis of excess deaths. With all four horsemen of the apocalypse currently in play in the world – and we may add two more horsemen playing havoc in New Zealand, malnutrition and homelessness – excess deaths may be becoming the global rule rather than the pandemic exception. We are not all going to live longer than in the past; the cliché “we are all living longer” is becoming, increasingly, a grossly insensitive justification for delayed retirement and public pension cutbacks.

*******

Keith Rankin (keith at rankin dot nz), trained as an economic historian, is a retired lecturer in Economics and Statistics. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand.