Analysis by Keith Rankin.

Australasia

Now that we are having to confront what a post-covid world may look like, it is important to get a sense of respiratory viruses in context, and especially to appreciate the extent that they determine the timing of our deaths; death being the great certainty of life.

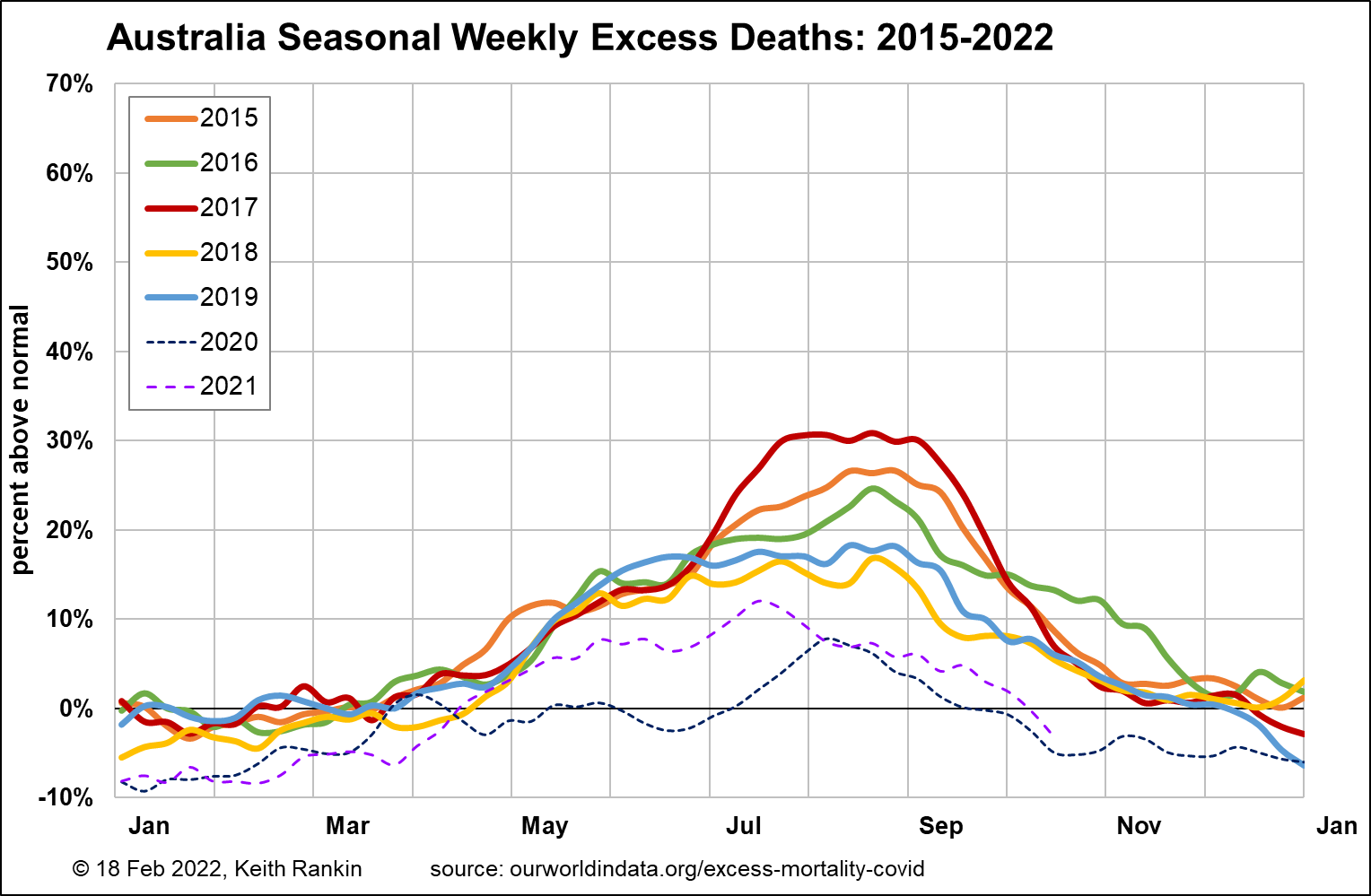

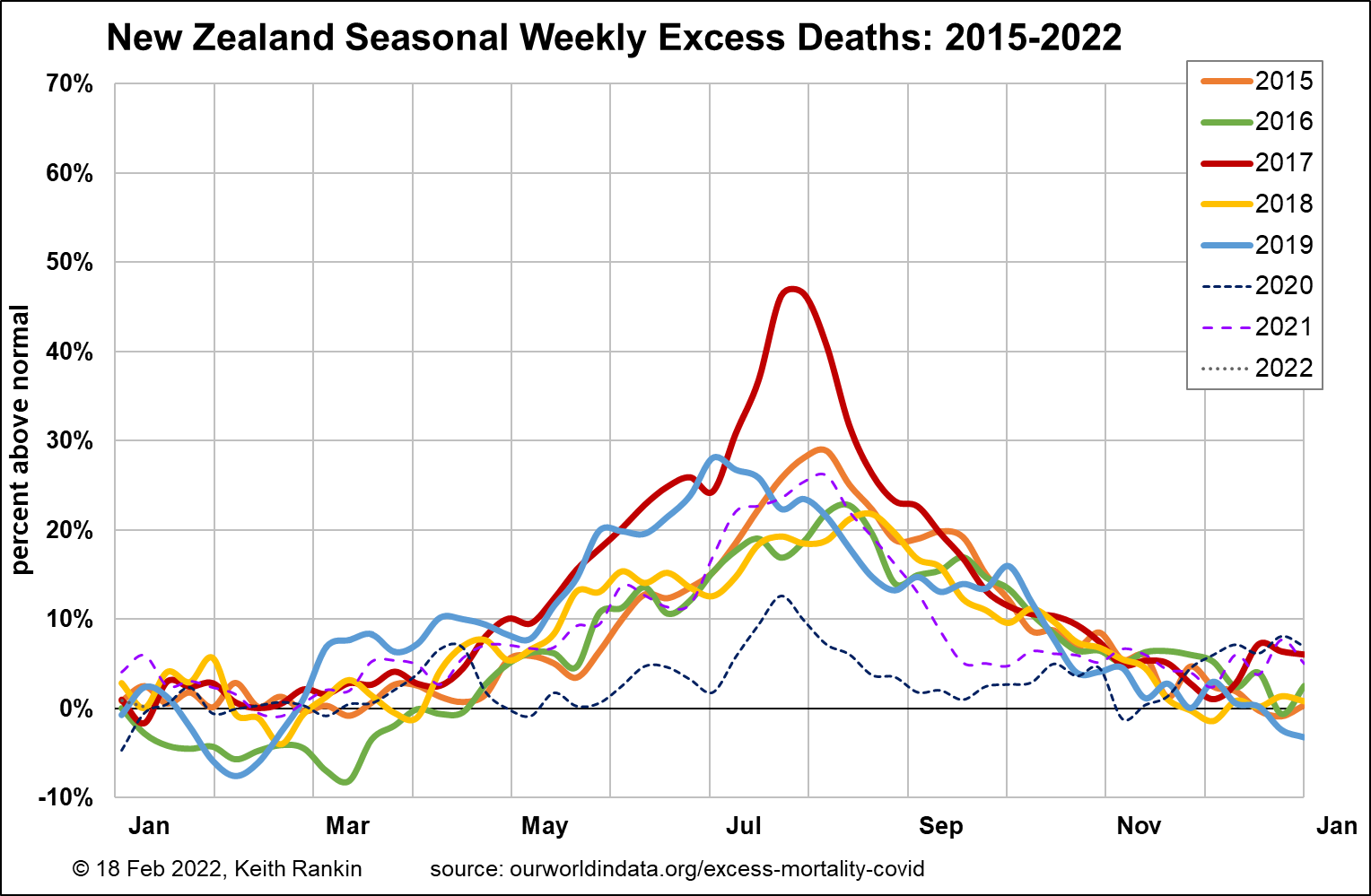

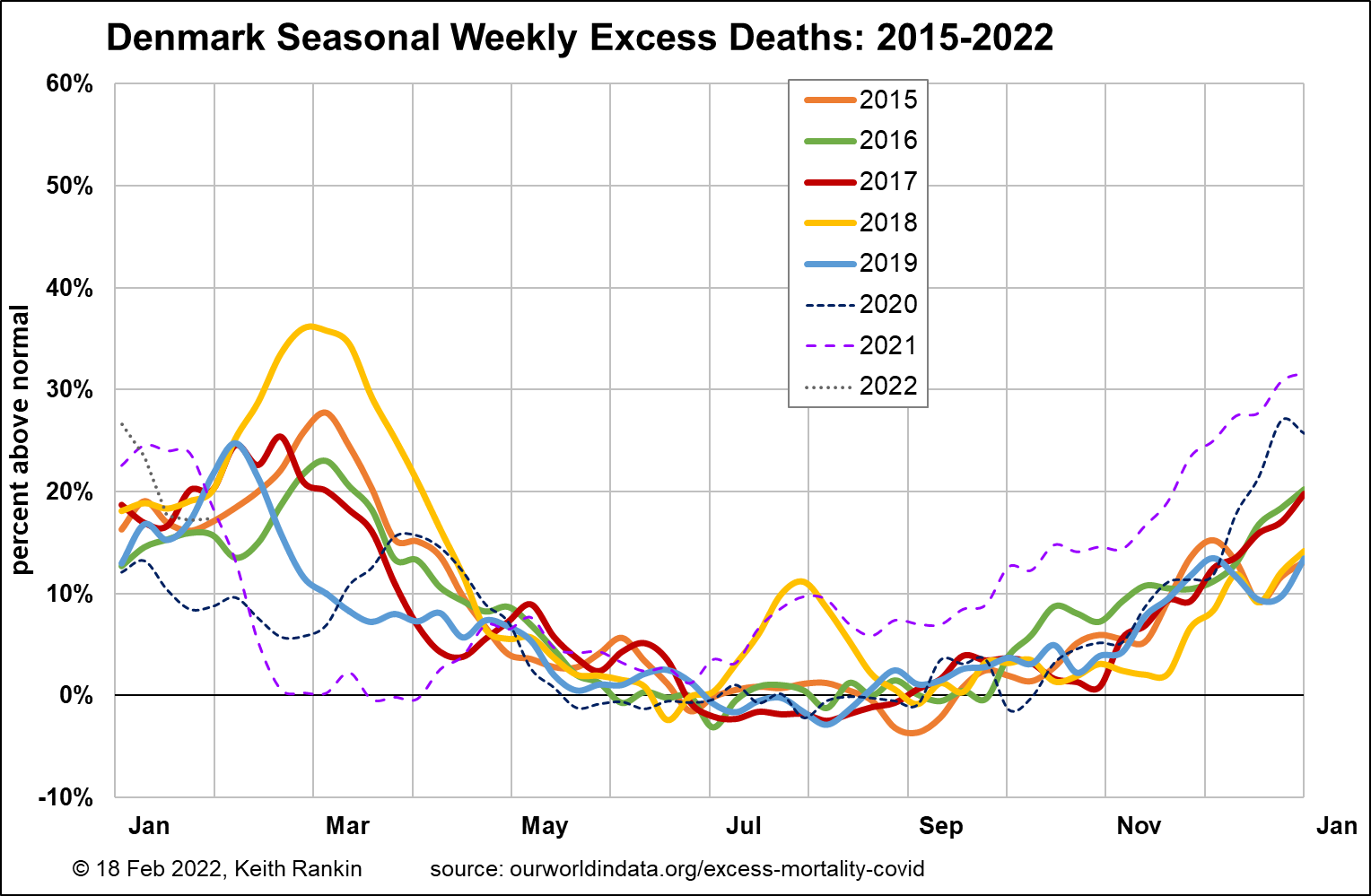

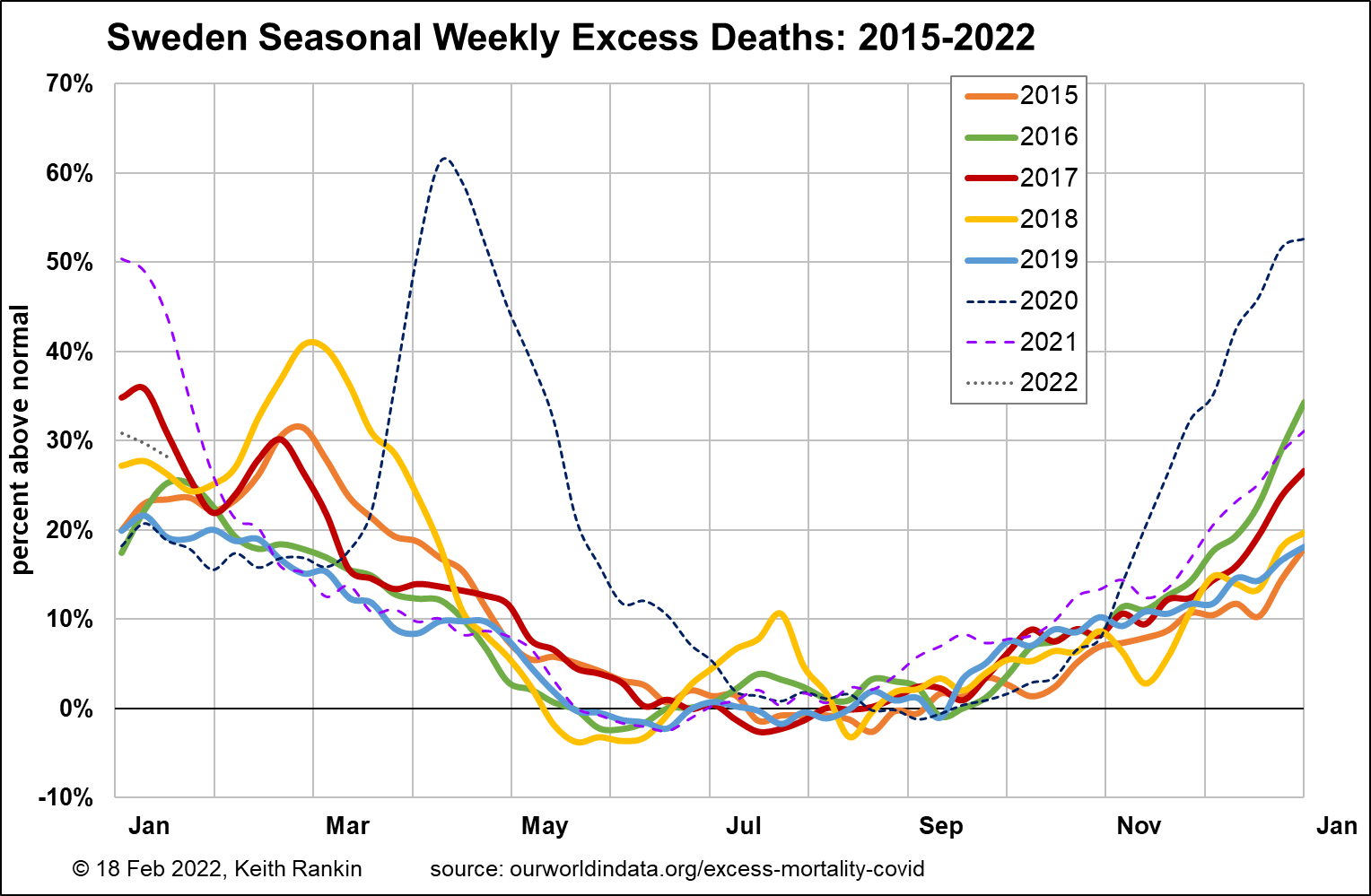

The first five charts here are all drawn to the same scale, for comparative purposes.

For each country, and for each year from 2015 to 2019, I have established a baseline ‘norm’ for months in which seasonal determinants of death are at their minimums. I have done this by sorting total weekly deaths’ from lowest to highest, and then taking the 6th-lowest to 14th lowest weekly totals, and averaging them. (Nine data points represents two low-death months; but not the very lowest, which may be unusual.)

I have also calculated, from the 2015 to 2019 data, an average rate of change of baseline deaths, which can be applied to the unusual years of 2020 to 2022. Baseline death totals increase when: populations grow, populations age, or when populations face increased non-seasonal threats.

Australia, unfortunately, is very tardy at releasing its total death numbers. So, while we have very up-to-date data for people who have died with covid, data required here is only available until mid-October. Thus, the chart is not able to register the spring wave of delta-covid deaths in Victoria and New South Wales.

For Australia, we see significant epidemic influenza waves in 2015, 2016 and 2017; less so in 2018 and 2019. Deaths have been well down from December 2019. (The bushfire summer of 2019/20 is associated with an unusually low overall death rate, and may reflect health and safety measures taken in the most affected states, again Victoria and New South Wales.)

If we ignore the epidemic peaks of 2015 to 2017, we see that there is still a substantial winter seasonal component – from May to October – to mortality in Australia. Since covid, Australian deaths have been markedly lower, due in the main to the relative absence of seasonal respiratory viruses. Nevertheless, 2021 suggests a limited return to normal. 2020 is an exception, without hints at all of common winter illnesses; the peak in August 2020 is the covid outbreak in Victoria. These seasonal deaths are triggered by endemic respiratory viruses – common colds, to give a generic name – which are more likely (especially in the over 85 age group) to lead to complications such as pneumonia. Given that we all must die of something, seasonal pneumonia is one of the most common form of deaths that are otherwise attributed to ‘old age’.

We might also note that, the statistical reality of lower total deaths in Australia should not be taken as a preference for a new social contract for a future society that attempts to create a liberty-safety trade-off; a trade-off in favour of more government-mandated-safety and less personal autonomy. Further, any attempt to forge such a social contract can easily backfire on its own terms, with (in a society with less fun) increased numbers of deaths triggered by non-seasonal and often stress-related conditions.

For New Zealand, the pattern is the same as Australia, but with three differences. First, in 2017, the epidemic flu – part of an undeclared pandemic that was substantially worse than the 2009 ‘swine flu pandemic’ – was both earlier and more severe in New Zealand. Second, the return in 2021 (and July 2020) of normal winter illness was much stronger in New Zealand than Australia. In 2021, there will have been a link to the ‘Trans-Tasman Bubble’, which allowed additional common cold strains – strains which Australians were more immune to – to enter New Zealand. Third, 2019 was a bad year for deaths in New Zealand, including a respiratory event early that winter.

One important point to note about New Zealand is that, even in early February, nearly 10 percent of its sequenced cases are the delta variant, not omicron. This means pre-omicron covid remains a significant problem in New Zealand. Some people getting seriously ill from covid will have the more severe variant without knowing that.

Denmark, Sweden, Austria

In recent months, on the covid front, we have heard much more about Denmark and Austria than about Sweden. Certainly, amongst Western Europeans, there is a general proclivity in Scandinavia to keep government health mandates are short as possible; and Scandinavians have generally been the most resistant in Western Europe to facemask wearing, but less resistant to vaccination.

In Denmark, we can easily see the seasonal flu peaks in February and March. There was no flu season in the winter of 1919/20. Covid came like a late flu in March/April 2020, and various public health measures substantially reduced the scale of this alt-flu outbreak, making it the equivalent – for mortality purposes – of a small wave of epidemic flu. The peak was higher than indicated, because covid mortality was offset by non-covid non-mortality. We note that there was a significant summer flu outbreak in 2018; these summer waves are not uncommon in other countries, and appear to be driven by high people-mobility in July and August.

In December/January 2020/21, covid came as an early flu, with public health measures again offsetting the covid mortality. The public health measures came off in April, leading to a few months of early-summer normalcy.

The covid-delta wave came in July, as natural immunity was waning, and when many Danes were still unvaccinated (although a larger percentage of Danes were vaccinated – and recently vaccinated – in July 2021 than people in most other countries). Death rates continued to be well-above normal for the rest of 2021, though these were for the most part not counted as Coviddeaths. Many of these will have been people who would have passed in early 2020 or early 2021 had these been normal flu years. (Certainly age data for covid deaths in Denmark in later 2021, not shown here, supports this view.)

For Sweden, we see the same epidemic flu episodes as Denmark, but not the 2019 one. So Sweden had had two winters of no flu ‘cull’. That will be one reason why Sweden had more covid deaths – again, overwhelmingly in the oldest age cohort, in April 2020 than Denmark. (So many who died in April 2020 would normally have died earlier from epidemic flu.) The other reason is that Sweden took few public health measures; in particular Sweden was very late to embark on mass covid-testing, and thus residential care homes got substantial covid outbreaks. In particular, the protracted downside of the April/May 2020 outbreak was linked to Sweden not going into lockdown.

The winter 2020/21 outbreak in Sweden was bigger than in Denmark (again mainly due to the lack of non-covid non-deaths which arise from lockdowns in particular), though smaller than for most other West European countries (eg see Austria below). Important for Sweden is that excess deaths for May 2021 were noticeable fewer than for Denmark. And Sweden is the country – more than any other, which rejected the mandatory use of facemasks – and indeed for which the voluntary use of facemasks was reputedly low. Sweden’s resilience during the covid-delta outbreak was stunning, with the mid-winter peak being almost the same as a typical flu peak.

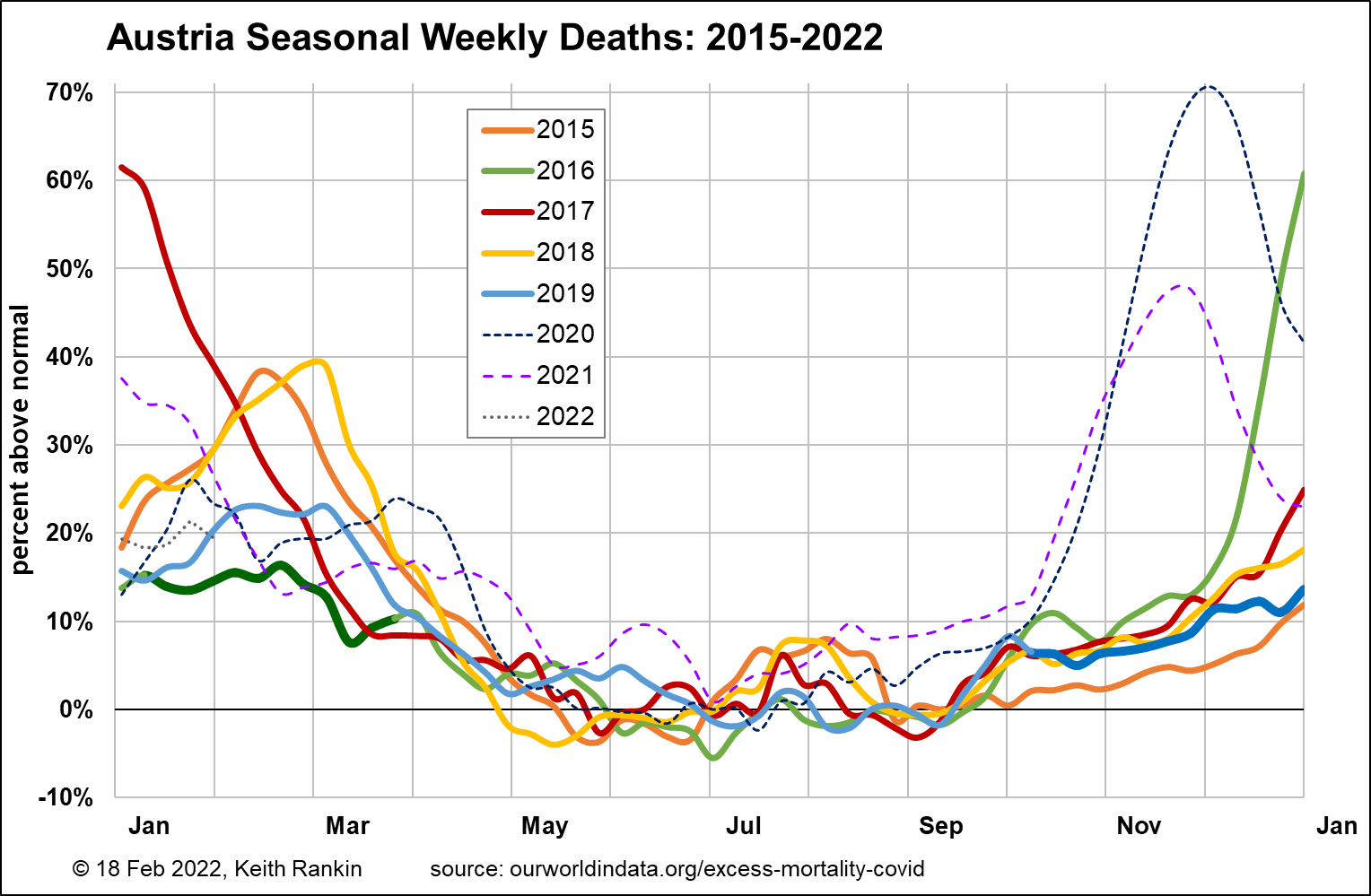

Austria provides another interesting comparative insight. The impact on mortality of non-flu non-covid ‘colds’ is shown by the thick green and blue winter ‘baselines’. In addition, Austria has flu peaks more substantial than those apparent in Scandinavia.

In Austria, despite being one of the countries from which covid spread into Western Europe (via the ski-fields), had a low covid mortality in March and April 2020. This will be due to three factors: public health measures, the preponderance of foreign holidaymakers on the ski-fields in the February school holiday break, and the fact that Austria did have a flu wave in January 2020.

Austria had covid much worse than either Sweden or Denmark in both late 2020 (original variant) and late 2021 (delta variant). The 2020 ‘second wave’ will have been largely because the first wave had been so muted; ie people who in other countries would have died in the first wave ended up dying in the second 2020 wave. (Both waves particularly affected the 75-84 age group. (Due to World War 2, there will have been a significantly smaller 85+ age cohort in Austria than in Sweden.)

Covid-omicron appears to have had no impact on mortality in any of these three countries.

Colombia

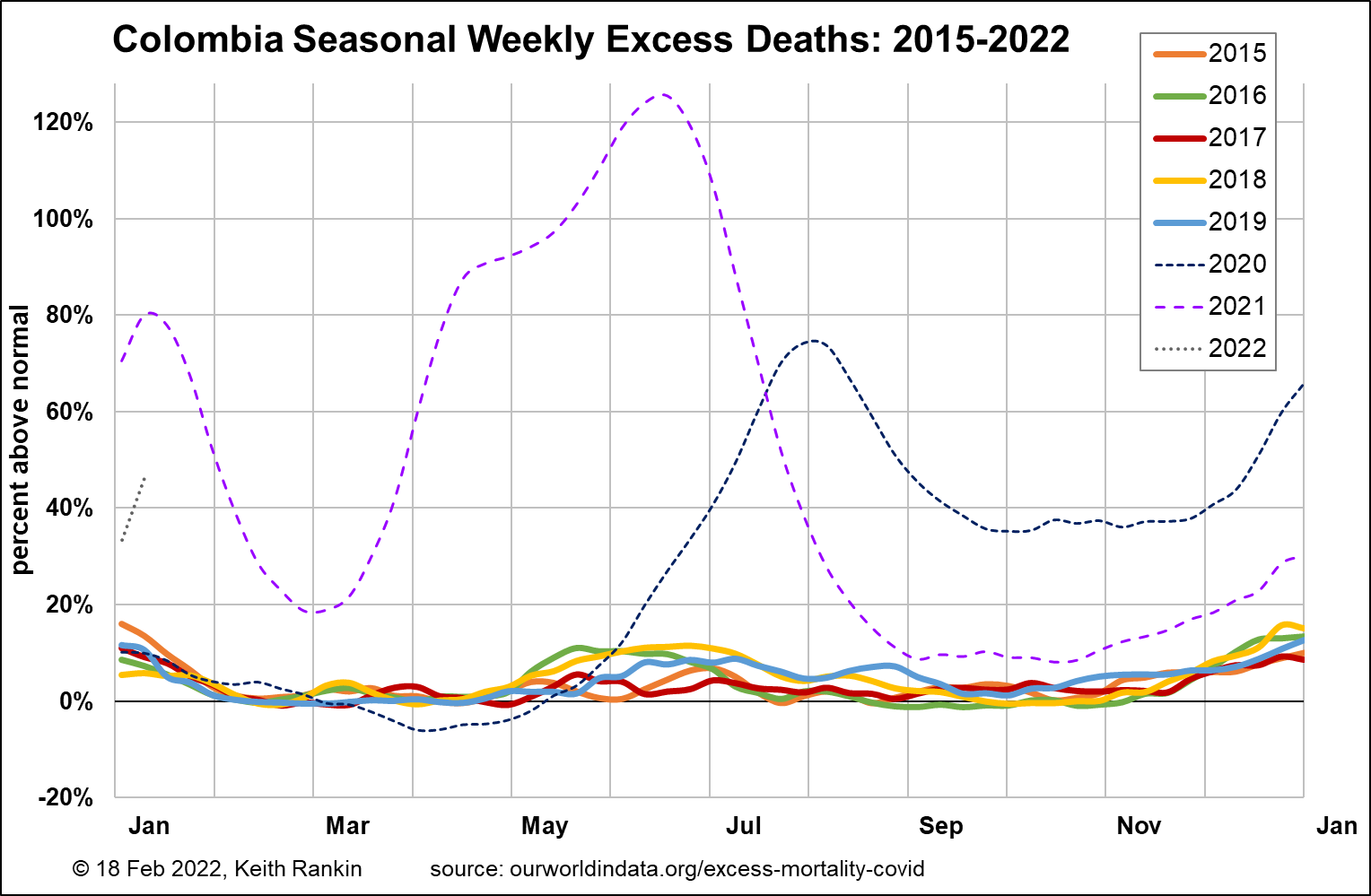

Finally, I have included Colombia as the best example of an emerging tropical country with a largely temperate climate. Colombia doesn’t have seasons in the way European and Australasian countries do. It had a 2019 life expectancy just below that of the United States.

The scale is different on this chart, because the scale of Covid19 was so much greater in Colombia. We should also note that Colombia was very late to get its waves of heavy covid mortality. Colombia had embarked on a very successful – yet ultimately very unsuccessful – programme of public health measures.

Colombia appears to have been particularly vulnerable to covid for two reasons.

First, because it does not have ‘seasonal’ epidemic or endemic waves of respiratory mortality. This geographical circumstance might mean that Colombians are surprisingly healthy in normal times. But adds to the vulnerability of Colombians in abnormal epidemiological times.

Second, Colombia’s successful public health measures appears to have added significantly, to the vulnerability of this already vulnerable population. We also note that almost all the death from covid so far in Colombia has arisen from pre-delta variants. By the time that delta arrived, Colombia’s surviving population was substantially immune to delta.

Deaths are on the rise again in Colombia. In mid-December, 93 percent of covid in Colombia was delta, not omicron. The deaths in early January are due to covid-delta.

Conclusion

Most temperate countries have significant numbers of deaths that are triggered by epidemic and endemic respiratory viruses that are not Covid19.

And the most covid-resilient country, above, is clearly Sweden. Overall, Sweden’s mortality experience from covid is consistent with its experience from other respiratory viruses. Further, Sweden’s (and other western high socio-economic countries) high general life-expectancy may be partly because of – not despite – its ongoing experience of epidemic and endemic viruses; an experience that may help keep population immunity well-tuned.

*******

Keith Rankin (keith at rankin dot nz), trained as an economic historian, is a retired lecturer in Economics and Statistics. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand.