Analysis by Keith Rankin.

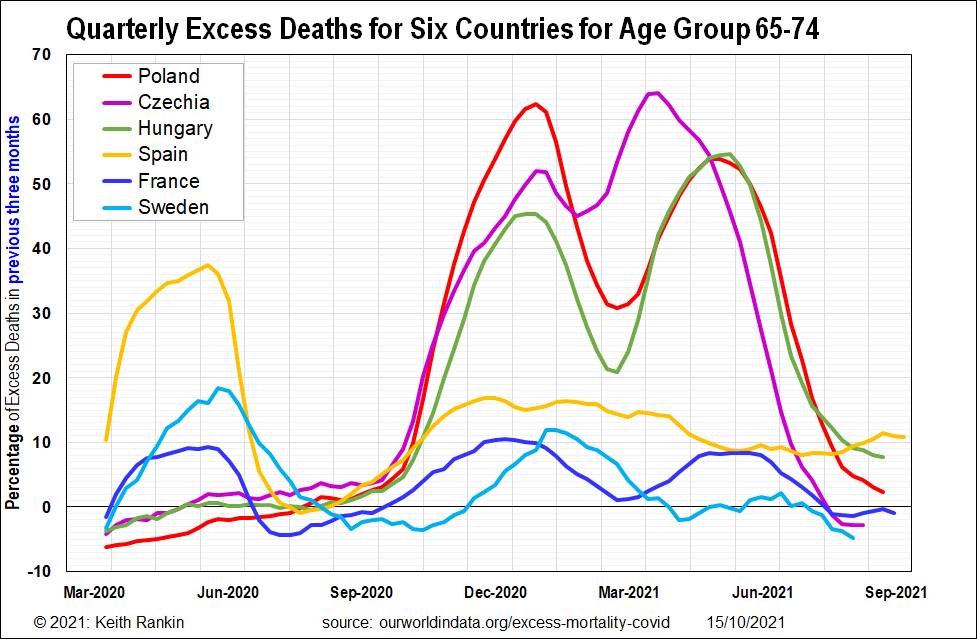

The above chart poses one clear question. Why is the experience of the three relatively prosperous East European EU countries (Poland, Czechia, Hungary) different to that of the three West European EU countries (Spain, France, Sweden).

The ‘research hypothesis’ posed here is that, while all these countries were naïve to the Covid19 (SARS-Cov2) novel coronavirus at the time of their first exponential outbreak of Covid19, the East Europeans were substantially more naïve to the endemic ‘common cold’ coronaviruses. (While this is the formal research hypothesis, the definition of ‘endemic coronaviruses’ can be extended informally, if required, to include other common cold viruses – mainly rhinoviruses – and can indeed be extended even further to include seasonal influenza viruses.) The second part of the hypothesis is that coronavirus immunity – however acquired – wanes more quickly than most other classes of virus.

The data shown starts in March 2020, when only Spain – of these six countries – had any significant death toll from Covid19. Also, the data only includes deaths of people born between 1946 and 1956, the post World War 2 generation. This is helpful, because, for the most part, these people are not dying from other causes, though there is nevertheless a substantial baseline of normal deaths for this group, from cancers and heart disease for example. Focussing on a single post-war age cohort substantially removes distortions arising from different age structures of different countries’ populations. Finally, I focus on this age group because it is my age group.

The chart shows the three West European countries undergoing exponential increases in excess mortality in April 2020; increases that match up with official records of Covid19 deaths in these countries. This data points to the beginnings of the pandemic in these countries being February 2020 (Spain probably in January 2020). The three Eastern countries show no sign of any substantial exposure to the Covid19 virus until September 2020, noting that the each country’s epidemic outbreak exposure occurs at least a month before the exponential rise in deaths.

The first wave of Covid19 in the Eastern EU coincides with the second wave in the Western EU – the ‘autumn wave’. The autumn wave is substantially less virulent in the west than in the east, presumably because the western populations had acquired a degree of immunity to Covid19.

What is most pertinent, however, is to compare the first wave in the east with the first wave in the west.

On the onset of each first wave, the host populations of all six countries can be considered approximately equally naïve to the Covid19 virus as each other population. Yet, the eastern countries suffered a much worse – more virulent – first wave than did the western countries.

In September 2020 there were no identified new covid strains, and no vaccines. All six European countries had populations with similar life expectancies. All were equally naïve to Covid19.

My research hypothesis suggests that they were not equally naïve to coronaviruses, as a viral family. Common cold coronaviruses probably circulate more in winter than in summer; at least we notice their symptoms more in winter. So the autumn is probably a more risky time to catch a cold. But not to the extent that can explain the huge differences shown in the chart.

The main thing that was different at the beginning of September compared to the beginning of March was that all six countries’ populations had taken broad-spectrum public health measures – a mix of voluntary and compulsory measures – to suppress the circulation of coronaviruses (and other respiratory viruses); ie not just measures that narrowly targeted the Covid19 coronavirus.

If, as hypothesised, coronavirus immunity wanes relatively quickly, then, around September, all six countries’ populations would have been significantly less immune to endemic coronaviruses than they would have been in other years, at that time of the year. However, a substantial minority of people in these western countries would have been naturally immunised against Covid19.

In September 2020, the Covid19 virus was substantially the most preponderant coronavirus in circulation in Europe. The western population, though lacking immunity from other coronaviruses, had a significant degree of immunity against Covid19; and also some immunity against the common cold viruses because SARS-Cov2 antibodies would most likely have provided some protection against the common cold.

Eastern Europe had no protection against Covid19; no recent exposure to SARS-Cov2 nor to any other coronavirus. The public health measures had wiped much of the normal coronavirus immunity, and there had been no opportunity to gain immunity to SARS-Cov2. The high coronavirus death toll in the east was mainly due to Covid19 (statistically verified by official Covid19 death counts). Also, while the age group in question rarely dies from endemic coronaviruses, any common colds that did occur that 2020/21 winter may have been more severe than in previous winters.

The western countries in March 2020 were protected – in part – by normal seasonal immunity to endemic coronaviruses; at least according to my hypothesis, and supported by the evidence presented. They were naïve to Covid19, but not to other coronaviruses. However, when waves of Covid19 hit Eastern Europe, in August and September 2020, Eastern Europeans were largely unprotected against all coronaviruses; immunity against any one coronavirus was unavailable to help people (‘viral fuel’, to use a forest fire analogy) to fight any other coronavirus.

I am open to any other interpretation of the above evidence. (See contact details below.) The question is: why did Eastern European EU countries suffer much more from their first wave of Covid19 than did Western European countries during their first wave.

Implications for 2021 and 2022

The inference is that all immunity – by vaccination or by exposure – to coronaviruses wanes sooner than for most other virus classes. And that immunity to one coronavirus confers some immunity against other coronaviruses.

This means that some public health measures – those which reduce general immunity to coronaviruses – have substantial medium-to-long-term costs in addition to their undoubted short-term benefits. (It’s like adrenaline or cortisol; prolonged release of these hormones imposes long-term health costs.) The main cost of extended lockdowns and other transmission-barrier methods is induced naivety to all classes of respiratory virus (and probably to other pathogen types as well). Indeed, this is almost certainly why Melbourne is suffering more from Covid19 in 2021, than is Sydney. (Melbourne is more like Czechia; Sydney more like France.)

Vaccination is not one of those ‘trade-off’ measures. Vaccination as a public health measure reinforces rather suppresses natural immunity, and possibly in a synergic rather than in an additive way. But, as natural immunity wanes, vaccination-induced immunity to coronaviruses also wanes; this gradual loss of immunity is one of the critical components of the present public health emergency that is not adequately communicated.

In this regard, we need to appreciate that there have been no previous successful coronavirus vaccines. Vaccination against coronaviruses is new territory. (Indeed, vaccination against influenza is also new territory; and, by and large, influenza vaccines have only been made available to older people who are familiar with the public health campaigns of the 1950s and 1960s. Vaccine resistance may be due in part to increased unfamiliarity with adult vaccines.)

I remember a conversation with a friend in 2003, at the time of SARS. I mentioned that I had heard that the SARS virus was a close relative of the common cold virus. He had heard that too, adding ‘that’s the worry’. He knew that there were multiple reasons why there had never been a successful vaccine against the common cold; and that ‘waning immunity’ was one of them.

For these six charted countries, in 2021 there are as yet no significant impacts from the highly transmissible delta-strain of SARS-Cov2. Immunity levels towards this virus remain high in these countries. Nevertheless, waning immunity will most likely become a problem in early 2022, if not addressed through revaccination. (I am concerned that vaccination in Europe has stalled, and that vaccination rates are far too low in these eastern countries.) The good news is that, just as endemic coronavirus exposure can give some protection against Covid19, so the Covid19 vaccine can give some protection against those annoying common colds so easily caught – in the past – from office colleagues and other passengers on public transport.

If we take one principle forward with us in the ‘fight’ against Covid19, it should be the principle that immunity is the critical component of our human defence, and that immunity to this particular class of viruses needs to be renewed on an ongoing basis. (Coronaviruses are not like measles, from which lifelong vaccination immunity is possible.) As Dr Jonathan Quick said “the future depends much more on what humans do than on what the virus does” (Covid 19 Delta: What the future holds for the coronavirus and us).

Keith Rankin (keith at rankin dot nz), trained as an economic historian, is a retired lecturer in Economics and Statistics. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand.