Analysis by Keith Rankin.

Russia is a former superpower with a long tradition of scientific achievement. It remains the world’s second largest nuclear power. Yet pre-covid life expectancy in Russia was just 72.6, and Russia has a higher median population than New Zealand, despite having comparatively few people aged over 80.

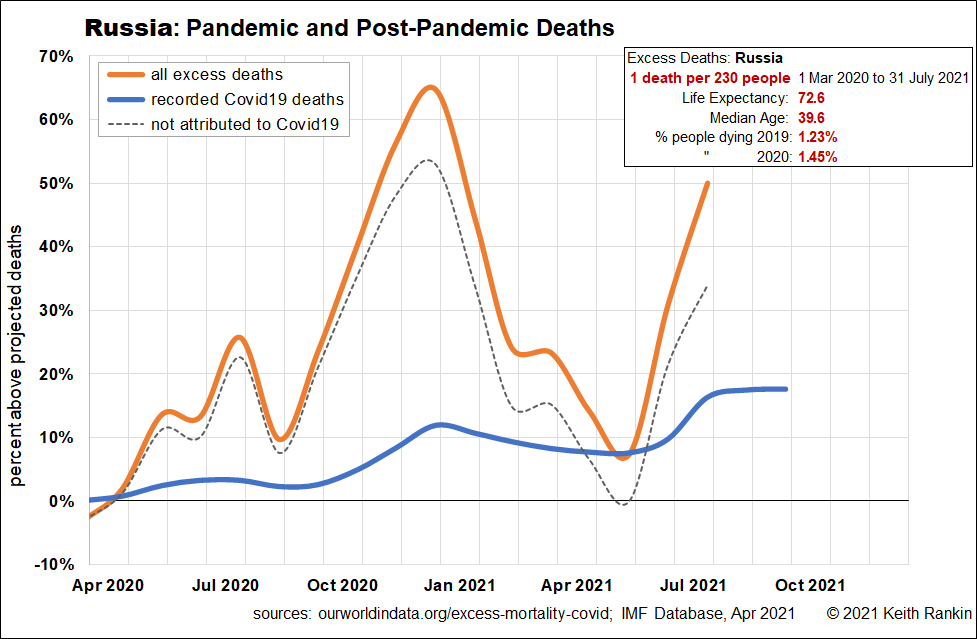

The Russian people have had a tough time with Covid19. Excess deaths from May to July 2020 were much higher than the official Covid19 death toll; there is little sign of public health measures. While August reflected a generally lower Covid19 toll in Europe, the autumn outbreak in Russia (of the Wuhan strain) was huge, peaking at a 65% increase in deaths in December.

While Russia’s alpha-strain outbreak in March 2021 was comparatively muted, the present delta-strain outbreak is massive, and again much higher than Russia’s official summer 2021 death rate. The present delta-strain outbreak has not peaked yet, according to official data. Overall, Russia’s already high death rate has increased by around 25% from March 2020 to July 2021.

By the time the pandemic is over, Russia may lose as many as 1 in 100 of its people either directly from Covid19, or as from resulting disruptions. Big factors here may include the use of a less effective vaccination, though low vaccination rates overall and waning natural and vaccination immunity would all appear to be contributing to Russia’s delta tragedy.

In Russia’s case, almost all of the excess deaths ‘not attributed to Covid19’ are due to Covid19, directly or indirectly. Certainly, to Russia’s credit, at least all deaths (from all causes combined) are registered. This is not the case for some countries in Asia and Africa.

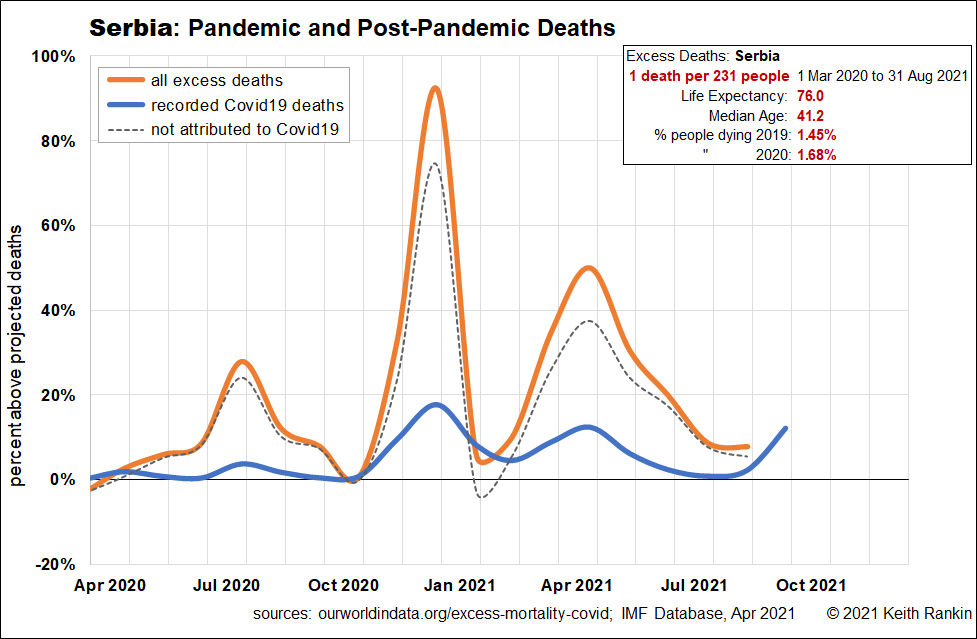

Serbia is interesting for three reasons. First, it has strong present and historical cultural links with Russia. (Indeed it was the Russia-Serbia defence pact that precipitated World War One – an unfortunate outgrowth of the Third Balkan War – following the assassination of the heir to the Austrian throne by a Serbian ‘freedom fighter’.) Second, Serbia did not show up in my charts earlier in the pandemic, even when other Balkan countries did. And, third, Serbia is now (first week of October) the country outside of the West Indies with the highest number of new reported cases per capita of Covid19.

Serbia’s life expectancy is higher than Russia’s; and its median age is older, presumably due to its having proportionately more octogenarians than Russia. Serbia has a similar excess death toll to Russia, though, unlike Russia, Serbia’s charted toll includes August 2021.

Looking at the chart, for Serbia we see similar May and July 2020 mini-peaks, though smaller compared to Russia. Serbia also shows a similar, but taller, December peak. This may be due to some reporting delays at a time that the health and reporting systems will have been overwhelmed. Serbia had a much bigger alpha-strain outbreak, which peaked in April 2021.

If there were any serious public health measures used, then non-Covid19 death rates should have fallen. If that was in fact so, then Covid19 deaths will actually be higher than the excess deaths shown.

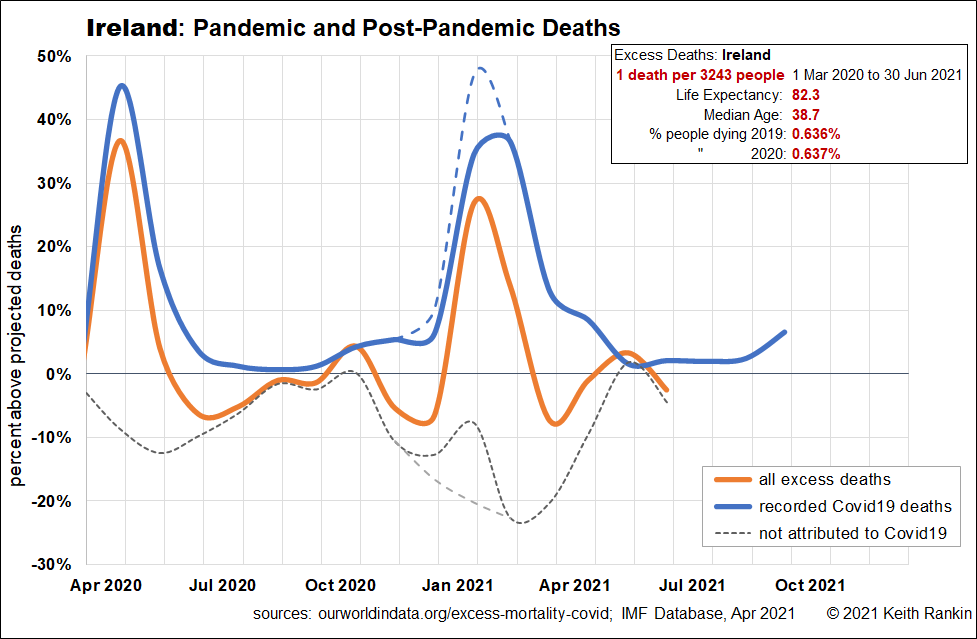

Ireland is interesting in part because its present demographics are all very similar to New Zealand’s. And it’s of interest because it has supplanted New Zealand from the top of Forbes’ list of countries that have best coped with Covid19. Ireland is also present here because it’s the only country in the European Union which publishes deaths monthly rather than weekly. (These countries, shown today, are all ones which report monthly.)

Ireland copped Covid19 very early; it already had a significant number of Covid19 deaths in March 2020. Strict public health measures soon followed, pushing excess deaths into negative territory. Effective emergency public health measures are revealed, in particular, by negative unattributed deaths. Or, put another way, with public health measures and accurate Covid19 death reporting, official Covid19 deaths exceed excess deaths; quite the opposite from Russia and Serbia.

Ireland, appropriately, relaxed its public health measures in its 2020 summer. Then it caught the next (spring) wave of Covid19, and clamped down hard. Nevertheless, Christmas Covid got through, and the clamps came down again. Ireland’s story in 2021 has been one of comprehensive vaccination. The delta-strain has had no impact until September 2021, and deaths will probably stay low this Irish autumn. My main concern here would be waning vaccination immunity, combined with less (and waning) natural immunity compared to Great Britain. I would not be surprised to see another Christmas death spike, though much less serious than last Christmas.

The extra (dashed) lines in the chart for Ireland represent an attempt to estimate the true scale of the January peak. It represents a further attribution of deaths to Covid19 in the context that public health measures were clearly and substantially reducing non-covid mortality. Ireland may see further deaths in 2022, as a result of other life-affecting conditions having been undertreated for much of 2021.

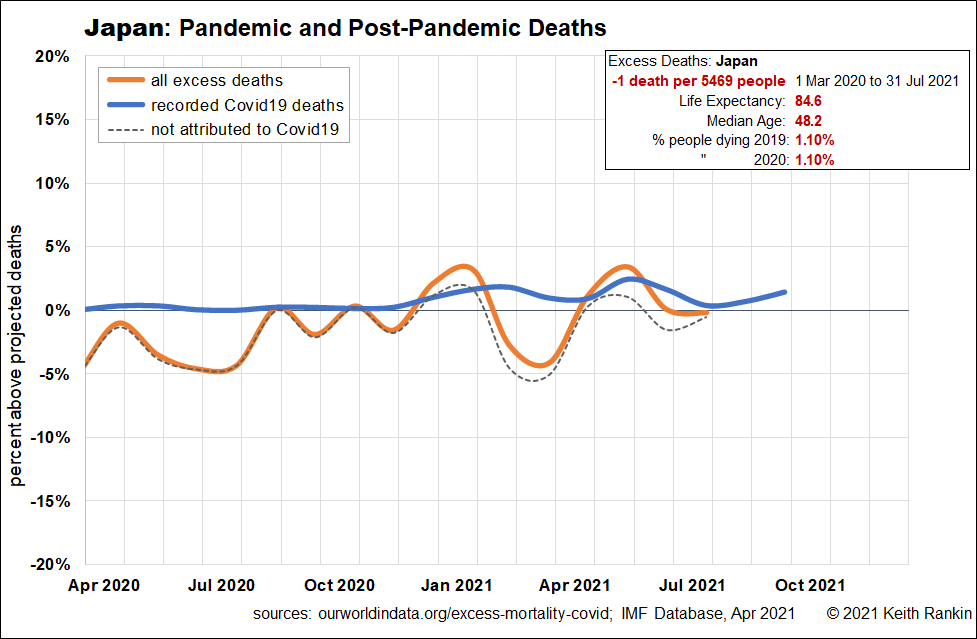

Finally, Japan. Refer to Covid-19 Delta outbreak: Japan baffles experts as cases suddenly plummet (NZ Herald, 7 Oct 2021). The first thing to note in the Japan chart is the low values of both the mortality peaks and troughs.

Japan is unusual in that it has a particularly old population. Hence, over one percent of its people die each year; high by New Zealand and Irish standards, but low by Russian and Serbian standards. Its life expectancy is, I understand, the highest in the world. So far, the death impact on Japan of Covid19 has been negative. It may well remain negative.

Japan, like Sweden, is a country of low inequality and marginalisation, and has people with a greater willingness than most to take responsibility for health outcomes. So, again like Sweden, in 2020 Japan introduced comparatively few public health mandates. And, like Ireland, Japan was one of the earliest countries to be affected by Covid19, in particular (but not only) due to the Diamond Princess cruise ship spectacle.

Overall, death rates fell, as Japanese people took their own precautions. Significant subsequent outbreaks occurred in January and May. The delta-strain outbreak in Japan, in July and August – well-known to the world because of the Olympic Games – seems to have had little impact on its death rate. And then, apparently, Covid19 has virtually disappeared, for now at least.

Japan has a good (though belated) vaccination rate. It seems to be that Japan retained high levels of natural immunity to respiratory conditions, mainly through the minimal use of public health mandates. (Interestingly, though many young Japanese wore facemasks when I was there in 2014, my impression from the Rugby World Cup of 2019 was that facemasks were much less fashionable in Japan in recent years.)

As in matters of macroeconomic policy – if anyone could afford a Covid Olympics then Japan could – I think that New Zealand and other countries should properly evaluate what happened (or didn’t happen!) in Japan. Interestingly, Japan is the country with “the world’s highest debt” if we use that expression in the way that the media refer to macroeconomic debt. (In fact, Japanese people have very low debt, but the Japanese government has the world’s highest government debt relative to GDP.) This debt – owed and owned by Japanese – is in fact Japan’s solution, not its problem.

Other Countries

I plan to publish similar charts for a number of other countries in the next few weeks. Getting the numbers correct poses some technical challenges; this will be even more so when charting countries which publish registered deaths weekly rather than monthly. These charts will tell the true story of how Covid19 has impacted on Europe, the Americas, and a few Asian countries.

Keith Rankin (keith at rankin dot nz), trained as an economic historian, is a retired lecturer in Economics and Statistics. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand.