Analysis by Keith Rankin.

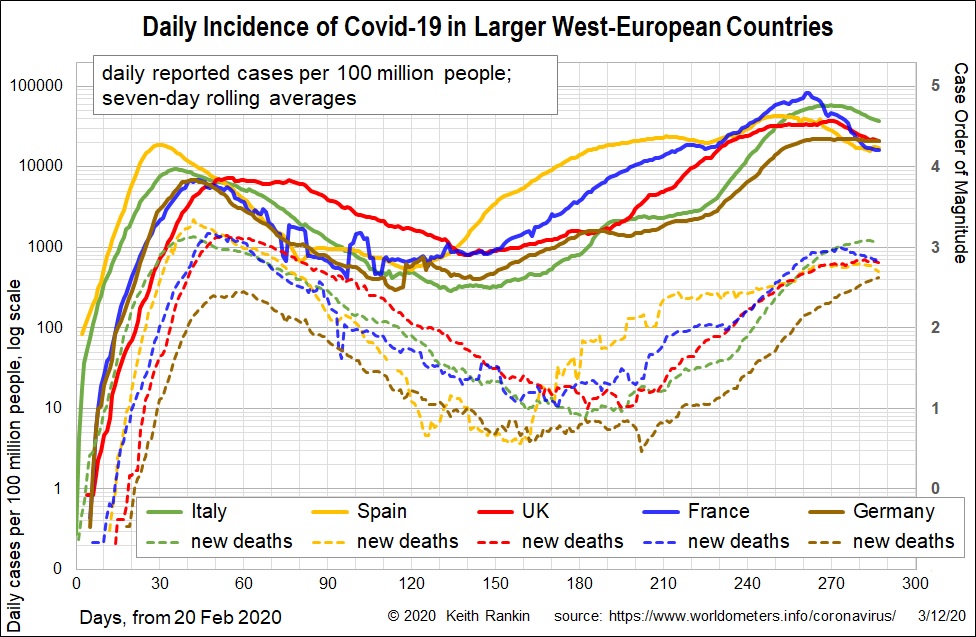

This week, Covid19 cases in most large European countries are passing their peak following four months of exponential growth, thanks to belated new ‘lockdown’ restrictions. The exception – or laggard – is Germany, which has generally been praised as the European exemplar of how Covid19 should be managed. Germany has converged with the other four shown.

The same general story applies to Covid19 deaths, which are now peaking; though France has peaked and Germany has yet to peak.

Look at the beginning of July, around days 130 to 140. In July I heard a report on the media suggesting that Spain’s resurgence of cases was being caused by British tourists. The chart is consistent with that story.

In June 2020, the United Kingdom had Covid19 cases and deaths about half an order of magnitude higher than the other big four western European countries. Spain is a particularly significant lifestyle and package tourism destination for British people. And British tourism represents a large part of Spain’s economy. We may also note that, for the most part, people fly from Britain to Spain, rather than catch a train or drive. Many British people will have had flights booked that they could not get refunds on; so, they flew to Spain (and also Portugal, and other places) rather than cancel their holidays. (I suspect there will not be nearly as many British sunseekers on the Iberian peninsula in the northern summer of 2021.)

Spain clearly led the way in the Covid19 restart in Europe, followed by close neighbour France; then Germany. France probably restarted Germany. Italy was last of the five to restart. Interestingly, Italy is a particularly popular holiday destination for Germans; the Italian wave seems to clearly follow that of Germany.

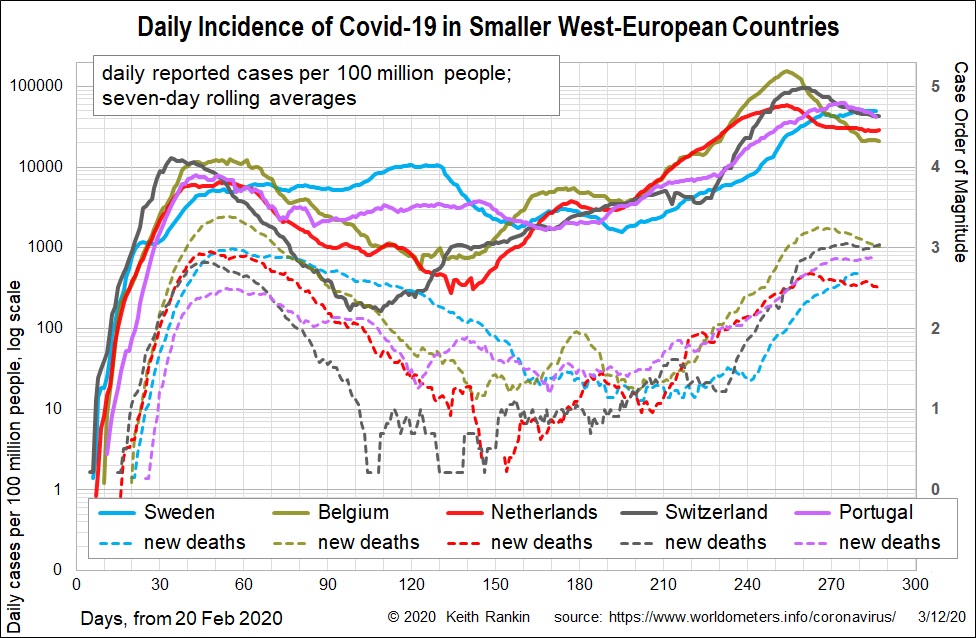

Looking at the smaller European countries, Sweden, Portugal and Netherlands standout as being particularly slow to bring Covid19 under control, thanks to more lenient lockdowns. Netherlands – with its higher level of excess deaths and its refusal to take Covid19 testing seriously – will have been worse than Sweden at the first peak, and closer to Sweden on the way down.

Portugal is interesting. Its initial death rates were much lower, meaning its reported case data was closer than the others to the actual number of cases; ie Portugal has substantially less underreporting. Essentially, Portugal followed a strategy more like the developed Asian countries (excl. China) – more testing and more immediate follow-up, and less locking down. The problem for Portugal is that the Covid19 simply festered, albeit at a lower level than United Kingdom. The second problem for Portugal is that – like Spain – it is a major destination for British holiday makers. And it was more open to British tourism in May and June than was Spain. Thus Portuguese tourism may have played a significant role both in keeping Covid19 high in United Kingdom and in facilitating the restart in its neighbour Spain.

Sweden – more complete in its reporting than Netherlands, though a slow reporter – persevered with Covid19 longest in Europe in the first European wave, and was the last in western Europe to restart. It now (with Austria) has the highest case incidence in western Europe; at case magnitude 4.6, these countries are on a present par with the United States. Sweden, Netherlands and Portugal appear – once again – to be Europe’s recovery laggards; along with Germany mentioned above.

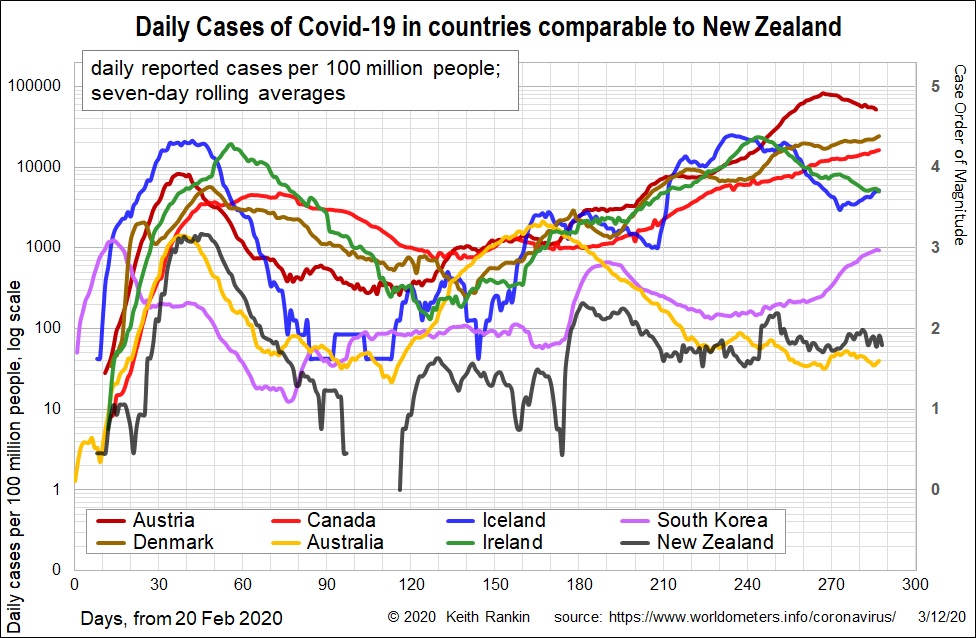

The third chart looks at countries with various similarities to New Zealand. (Austria represents a central European comparator.) Of particular note are Denmark and Canada. Denmark’s rise since July follows the general European pattern, though with a number of prominent stops and starts. Situated between Sweden and Germany, like them it is showing little evidence that the worst is over. Further, I understand that – at least compared to New Zealand (where facemasks are redundant because there are no community cases) and Sweden – people in Denmark and Germany do wear facemasks. My impression is that, while facemasks will have had some impact at the margin, the general story is that they fall well short of a substitute for lockdowns.

This conclusion is reinforced by the experience of South Korea, in a region where facemasks are more a part of the culture, cases have now returned to magnitude three, close to Korea’s peak in the first week or March 2020. If New Zealand’s border reopens in say March 2021, New Zealand’s incidence of Covid19 may also rise tenfold – to magnitude three – next winter. Mask use on Auckland’s buses is unlikely to have any impact, even at the margin, given that very few cases of Covid19 in New Zealand in 2020 have been contracted through the use of domestic public transport.

Canada also has had months of exponential growth of Covid19, despite mask mandates in the worst-hit provinces; it shows little sign of peaking. Canada was also like Sweden and Portugal and USA, with a very slow decline in cases after its initial April peak.

Today, Joe Biden says that Americans will have to wear masks for 100 days in the indoor spaces over which he will have the power to mandate. That sounds like a very good plan, quite different to the petty tyranny in New Zealand, where people riding Auckland’s near-empty buses are subject to an indefinite masking requirement. (Many of the drivers don’t bother, or wear their masks around their chins. Most passengers wear their masks only when they have to, and remove their masks on alighting.) Maybe we could have a referendum in 2022 – at the time of the local elections – for a decriminalisation of non-mask use on Auckland’s trains and boats and buses?