Analysis by Keith Rankin.

Income in an Economy

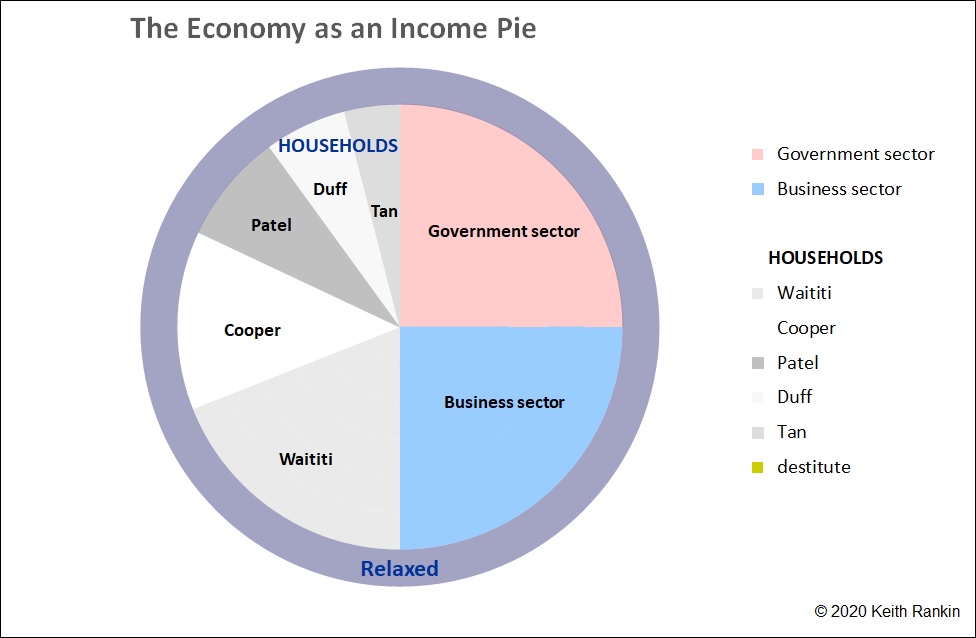

The chart above shows how income is distributed in an economy. It shows three major sectors: Government, Business and Households. Households are the principal sector; governments and businesses serve households, and are accountable to households. The chart is a pie chart, representing the economic pie. (For now, ignore the outer ring of the pie; the pie is the part divided into sectors.)

In this stylised example of a closed economy (ie no foreign sector), government receives a portion of national income (which is practically the same as gross domestic product). Part of the government income share goes to infrastructure, part goes to collective services like healthcare and education, and part goes on alms and other welfare payments. If the government sector – which includes local governments – saves part of its income, then it runs a surplus. (Repaying debt is a form of saving.)

The business sector both retains income and distributes income to households. The part that it retains – in blue – can be either invested on capital goods and services (eg buildings, machinery, staff training) or saved. If the sector as a whole saves part of its retained income, then the business sector runs a surplus. (Otherwise it runs a deficit, which is simply a negative surplus.)

The same applies to the household sector, represented here by six families: Waititi, Cooper, Patel, Duff, Tan and ‘destitute’. If the household sector saves more than it spends, then it runs a surplus.

By definition, the sum of the sectors’ surpluses adds to zero. So, if any sector is running a surplus then at least one other sector must be running a deficit.

The incomes shown represent entitlements to shares of the goods and services that contribute to the pie. For example, if the Cooper family run a business that makes barrels, then the business sector (or any other sector) may use part of their entitlement by purchasing those barrels. The profits from this cooperage business represent both income to the Cooper business and income to the Cooper household, enabling the Coopers to buy other stuff.

Surpluses and Deficits

If most households save part of their incomes, then the household sector most likely runs a surplus. (In most countries the household sector runs a surplus most of the time.) We generally expect the business sector to run a deficit about equal to the household surplus. That leaves the government sector with a balanced budget. However, if the business sector does not run a large enough deficit, then the government sector must run a deficit too. If, under these circumstances the government sector resists running a deficit, then not all the goods and services in the pie will be purchased, and the whole economy will shrink next year. (Imagine a missing slice from next year’s pie; that slice is called unemployment, or, strictly, ‘involuntary unemployment’.)

In this chart, debt is easily understood. Most likely the Waititi family does not wish to spend its full income entitlement; and maybe this year the Duff family wants to spend more than its income entitlement. So the Waititis can – directly or indirectly – transfer some of their present entitlement to the Duffs. The usual arrangement will be that the Duffs agree to transfer – directly or indirectly – a slightly greater amount from a future year’s pie to the Waititis.

The Waititis run a surplus this year, and the Duffs run a deficit. The Waititis contract to run a deficit in the future, so that the Duffs can run a surplus in the future. That is what a debt contract is; a commitment on the part of a creditor who runs a present surplus to run a future deficit, a commitment to be repaid. (The Waititis can defer this future obligation if sufficient new debtors can be found, in the future.)

Economic Growth

If next year’s income pie is bigger than this year’s pie (ie it contains more goods and services), we call that economic growth.

Inflation

The market may put a dollar value on this year’s income pie. If we produce essentially the same pie next year, but the market places a higher dollar value on next year’s version, then the economy has experienced inflation.

Relaxation

The ‘relaxation’ ring around the pie represents the extent that our economy is not ‘maxed out’; it’s the reserve capacity of the economy. It represents the ‘life’ part of a society’s work-life balance. (Economists call this ‘voluntary unemployment’; many do not realise that voluntary unemployment is a vital part of our wellbeing.) Our economic happiness is measured by the enjoyment that we get from consuming the goods and services that we buy, plus the opportunity to chill out and enjoy what we have.

We could increase our living standards by increasing the size of the relaxation outer ring, while keeping the economic pie the same size. Or, we could increase the size of the pie while keeping the size of the outer ring unchanged. While both possibilities reflect an increase in both living standards (aka economic happiness) and the productive capacity of the economy, only the second of these options would be measured as economic growth. Thus many economists have a growth bias in favour of that second option.

There are other options that represent increased economic happiness. The ‘relaxation’ option that needs to be mentioned here is to have a smaller income pie, and a bigger outer ring. This is the option that, coming out of the Covid19 pandemic, makes most sense. We will want to spend less – to buy fewer goods and services – while retaining a highly productive market-based economy. The solution to the Covid19 economic crisis is a structural readjustment to our work-life balance, maintaining economic capacity while spending and working less.

The Pie Chart representation has a Weakness

The sixth household – ‘destitute’ – does not appear on the pie chart, but does appear in the chart’s legend; the ‘legend’ is the table of labels to the right of the chart.

‘Destitute’ is statistically invisible, unless made visible by including it in the table. ‘Destitute’ has no income, no work-life balance. In this situation, the destitute household has little choice but to try to run a deficit, but will struggle to find a creditor. Failing that, destitute can only survive by alms, known by economists as income transfers.

Alms are good, but economic rights are better. Surely ‘destitute’ has some economic rights; rights that grant it at least some income from the pie? Yes, but only if society is grown-up enough to acknowledge and properly confer such rights. Otherwise ‘destitute’ remains visible only to those who will see.