Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Adrian Beaumont, Honorary Associate, School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Melbourne

The November 24 Victorian election will result in an upper house of 18 Labor out of 40 (up four since the 2014 election), 11 Coalition (down five), one Green (down four), three Derryn Hinch Justice, two Liberal Democrats, and one each for Animal Justice, Sustainable Australia, Transport Matters, Fiona Patten and Shooters, Fishers & Farmers.

Overall upper house vote shares were 39.2% Labor (up 5.8% since 2014), 29.4% Coalition (down 6.7%), 9.3% Greens (down 1.5%), 3.8% Hinch Justice, 3.0% Shooters, 2.5% Liberal Democrats, 2.5% Animal Justice and 2.1% Labour DLP. In regions where the DLP and Lib Dems were to the left of Labor and the Liberals respectively on the ballot paper, they had far higher vote shares through name confusion.

Labor won 45% of upper house seats on 39.2% of votes, and the Coalition 27.5% of seats on 29.4% of votes. The Greens won just 2.5% of seats despite 9.3% of votes, while Hinch Justice won 7.5% of seats on 3.8% of votes, and the Lib Dems 5% of seats on 2.5% of votes. Transport Matters and Sustainable Australia combined won 5% of seats on 1.4% of votes. This was not a good advertisement for democracy.

It is deeply disappointing that Labor made no effort during the last term to reform the flawed group voting ticket system.

Although the result is a bad outcome for democracy, Labor will probably be happy. If the Coalition opposes, they need three of 11 crossbenchers to reach the 21 votes needed to pass legislation. The Greens, Animal Justice and Patten are likely to be Labor allies on progressive legislation. In the last parliament, Labor, the Greens and Patten had 20 combined votes.

There are eight regions in Victoria that each return five members. A quota is one-sixth of the vote, or 16.7%.

In the federal Senate, voters are instructed to number at least six boxes above the line, though a single “1” above the line is still formal. Preferences are set by voters, not by parties.

The table below shows the actual results and what I believe the results would have been had the federal Senate system been in place. Under the Senate system, the most likely outcome would be 19 Labor, 14 Coalition, four Greens, two Shooters and one Hinch Justice. The actual results would probably match the federal Senate results in just two of the eight regions

Victorian upper house: actual results compared with results using federal Senate system.

In Eastern Metro, Labor had 2.22 quotas, the Liberals 2.17, the Greens 0.54 and the Lib Dems 0.25. Labor preferences would easily elect the Greens under the Senate system. Instead, Transport Matters won from just 0.62%, or 0.04 quotas.

In Northern Metro, Labor had 2.55 quotas, the Greens 1.00, the Liberals 0.99, the Socialists 0.25, the DLP 0.25 and Fiona Patten 0.20. Labor would win three seats under the Senate system, but lost its third seat to Patten in the actual count.

In South-Eastern Metro, Labor had 3.00 quotas, the Liberals 1.74 and the Greens 0.33. The Liberals would have won the last seat under the Senate system. Instead, the Liberal Democrats, with just 0.84% or 0.05 quotas, won the final seat.

In Southern Metro, the Liberals won 2.30 quotas, Labor 2.07 and the Greens 0.81. The Greens would easily win the last seat under the Senate system. Instead it went to Sustainable Australia, on just 1.32%, or 0.08 quotas.

In Western Metro, Labor won 2.78 quotas, the Liberals 1.28, the Greens 0.52 and Hinch Justice 0.41. With assistance from right-wing preferences, Hinch Justice would probably beat the Greens for the final spot under the Senate system. This is one occasion where the actual result would probably occur under a better system.

In Eastern Victoria, the Coalition won 2.05 quotas, Labor 2.02, the Greens 0.40, the Shooters 0.30, Hinch Justice 0.27 and the Lib Dems 0.24. The Shooters or Hinch Justice could have overtaken the Greens under the Senate system; the Shooters won the final seat, matching a possibility of the Senate system

In Northern Victoria, Labor won 1.91 quotas, the Coalition 1.87, the Shooters 0.47, the Greens 0.39, Hinch Justice 0.29 and the Lib Dems 0.23. If the Senate system applied, the results would be two each for Labor and the Coalition, and one Shooter. Instead, Labor won two, and the Coalition, Hinch Justice and the Lib Dems one each.

In Western Victoria, Labor won 2.29 quotas, the Coalition 1.80, the Greens 0.45, Hinch Justice 0.27, the Shooters 0.27 and Animal Justice 0.17. Under the Senate system, Labor preferences would have helped the Greens win the final seat, with the Coalition certain of a second seat. Instead, Labor won two, and the Coalition, Animal Justice and Hinch Justice one each.

Liberals retain Ripon after recount

In the lower house seat of Ripon, the Liberals trailed Labor by 31 votes on the provisional results, but won after a recount by 15 votes. Final lower house seat totals were 55 Labor out of 88 (up eight since the 2014 election), 27 Coalition (down 11), three Greens (up one) and three independents (up two).

Read more: Historical fall of Liberal seats in Victoria; micros likely to win ten seats in upper house; Labor leads in NSW

Newspoll: 55-45 to federal Labor

This week’s federal Newspoll, conducted December 6-9 from a sample of 1,730, gave Labor its third successive 55-45 lead. Primary votes were 41% Labor (up one since last fortnight), 35% Coalition (up one), 9% Greens (steady) and 7% One Nation (down one). This is the final Newspoll of 2018.

This is the third consecutive Newspoll in which Labor’s primary vote has exceeded 40%. Other than in the immediate aftermath of Malcolm Turnbull’s ousting, Labor’s primary had only reached 40% once since Julia Gillard’s early days as PM. Analyst Kevin Bonham says no government has recovered from such a dire position in aggregate polling to win with five months left.

In the final four Newspolls under Turnbull, the Coalition trailed by just 51-49. In the last three Newspolls, they have trailed 55-45. It appears that ousting Turnbull was a big mistake.

42% were satisfied with Scott Morrison’s performance (down one), and 45% were dissatisfied (up three), for a net approval of -3, down four points. Bill Shorten’s net approval was down two points to -15. Morrison led Shorten by 44-36 as better PM (46-34 last fortnight).

55% thought Labor would win the next election, while just 24% thought the Coalition would win. By 48-30, voters opposed Shorten’s plan to abolish franking credit cash refunds for retirees (50-33 in March).

By 46-40, voters did not think Turnbull was disloyal to the Coalition, though Coalition voters thought Turnbull disloyal by 56-34. By 56-36, voters thought Turnbull should be allowed to speak his mind, rather than keep his thoughts private. By 56-29, voters did not think Turnbull should be expelled from the Liberal party.

I think the Coalition’s best hope of winning the next election is for the economy to be very good, with strong wages growth. However on December 5, the ABS reported that the economy grew just 0.3% in the September quarter, well below expectations.

Essential: 54-46 to Labor

In last week’s Essential poll, conducted November 29 to December 2 from a sample of 1,032, Labor led by 54-46, a two-point gain for Labor since three weeks ago. Primary votes were 39% Labor (up four), 38% Coalition (up one), 10% Greens (down one) and 6% One Nation (down one).

Morrison’s ratings were 42% approve (up one since November) and 34% disapprove (down three), for a net approval of +8. Shorten’s net approval fell two points to -8. Morrison led Shorten by 40-29 as better PM (41-29 in November).

24% thought restricting negative gearing to new homes would lower house prices, 21% thought it would increase house prices, 27% make no difference and 29% didn’t know. 37% thought restricting negative gearing would increase rents, 14% lower them, 24% make no difference and 26% didn’t know.

53% thought Australia was not doing enough to address climate change (down three since October), 24% thought we were doing enough (up one), and 9% doing too much (up two). By 39-30, voters supported ending cash refunds from dividend imputation. The question was long, with information that many voters would not be aware of.

ReachTEL national and seat polls

A ReachTEL national poll for the Australian Youth Climate Coalition, conducted December 4 from a sample of 2,350, gave Labor a 54-46 lead. Primary votes were 38.2% Labor, 37.0% Coalition, 10.6% Greens and 6.9% One Nation. Sky News was commissioning ReachTEL polls once a month until June, but since then the only ReachTEL national polls have been from left-wing sources.

The Poll Bludger has details of ReachTEL polls in the Victorian federal seats of Corangamite and Higgins. The Liberals have no margin after a redistribution in Corangamite, and are trailing 59-41. In Higgins, the Liberals have a 10.3% margin, but are trailing 53-47. Seat polls are unreliable, but these are massive swings to Labor.

Facing heavy defeat, Theresa May postpones Commons vote on Brexit deal

UK Prime Minister Theresa May’s Brexit deal with the European Union was scheduled to be voted on by the House of Commons today. But faced with many defections from both the left and right of her Conservative party, and unhelpful opposition parties, May has pulled the vote.

The problem for May is that there is probably no deal that is agreeable to the European Union that can pass the Commons. Unless a deal passes the Commons, or some other option like a second Brexit referendum passes, the UK will crash out of the European Union on March 29, 2019. Such a “no deal” Brexit is likely to greatly damage both the UK economy and the Conservative party – see my personal website for more.

– ref. Victorian upper house greatly distorted by group voting tickets; federal Labor still dominant in Newspoll – http://theconversation.com/victorian-upper-house-greatly-distorted-by-group-voting-tickets-federal-labor-still-dominant-in-newspoll-108488

“These disconnections are compounded by limited understanding of the role of international human rights and economic law, as well as the norms of indigenous peoples, development partners and private companies.” Image: David Robie/PMC

“These disconnections are compounded by limited understanding of the role of international human rights and economic law, as well as the norms of indigenous peoples, development partners and private companies.” Image: David Robie/PMC Professor Derrick Armstrong speaking with other members of the final “creative tension” panel at the DevNet 2018 development studies conference. Image: David Robie/PMC

Professor Derrick Armstrong speaking with other members of the final “creative tension” panel at the DevNet 2018 development studies conference. Image: David Robie/PMC

Family snapshots … Dominguis and Dolfintje Dimara. Right: Dolfintje Dimara and with their first child. Image:

Family snapshots … Dominguis and Dolfintje Dimara. Right: Dolfintje Dimara and with their first child. Image: Dolfintje Imbab Dimara with her sister and grand niece in Jayapura. Image:

Dolfintje Imbab Dimara with her sister and grand niece in Jayapura. Image:

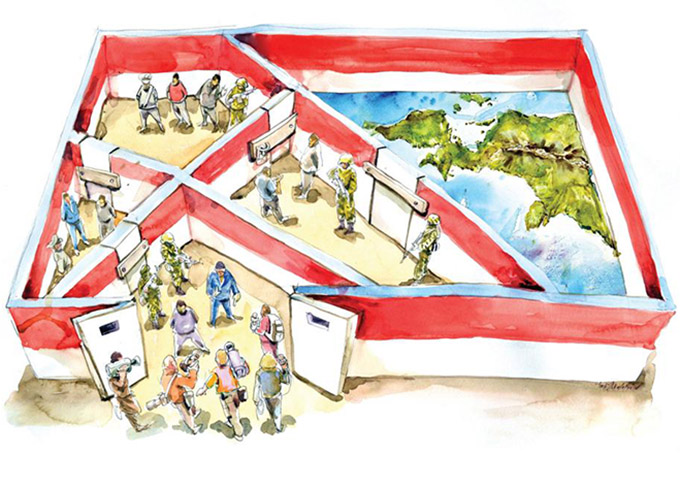

Indonesian police prepare to face peaceful Papuan protesters in the capital of Jayapura this week. Image: Voice Westpapua

Indonesian police prepare to face peaceful Papuan protesters in the capital of Jayapura this week. Image: Voice Westpapua Priests, seminarians and students take part in a peaceful Human Rights Day march in the capital Jayapura this week. Image: Voice Westpapua

Priests, seminarians and students take part in a peaceful Human Rights Day march in the capital Jayapura this week. Image: Voice Westpapua

Documentary producer Amiria Ranfurly (left) and director Wiktoria Ojrzyńska … “intimate frontline climate stories”. Image: COP24 Pacific

Documentary producer Amiria Ranfurly (left) and director Wiktoria Ojrzyńska … “intimate frontline climate stories”. Image: COP24 Pacific