ANALYSIS: By Albert Schram

This article attempts to put the current governance crisis at the Fiji-based University of the South Pacific (USP), one of only two regional universities in the world, in a broader regional perspective. If Pacific regional integration and coordination means anything, then this would be a good moment to demonstrate it values academic freedom and institutional autonomy and good governance at the regions’ universities. The author, former vice-chancellor of the University of Technology in Papua New Guinea, revisits a study he did in 2014 about the PNG university system published in USP’s Journal of Pacific Studies [Schram, 2014].

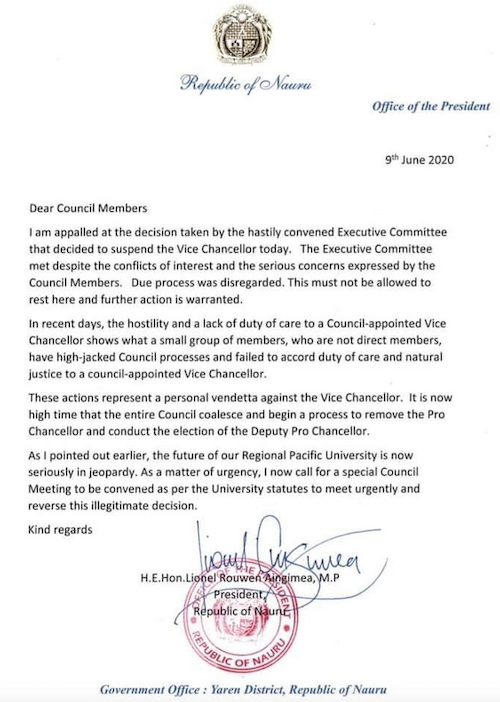

During the last weeks, after reports emerged about gross mismanagement and breaches of the rules of the university at USP under the former administration, this week the Executive Committee of the University Council decided to suspend the current vice-chancellor for alleged “misconduct and breach of rules and procedures”, despite all the evidence pointed in the opposite direction of the former administration and some council members.

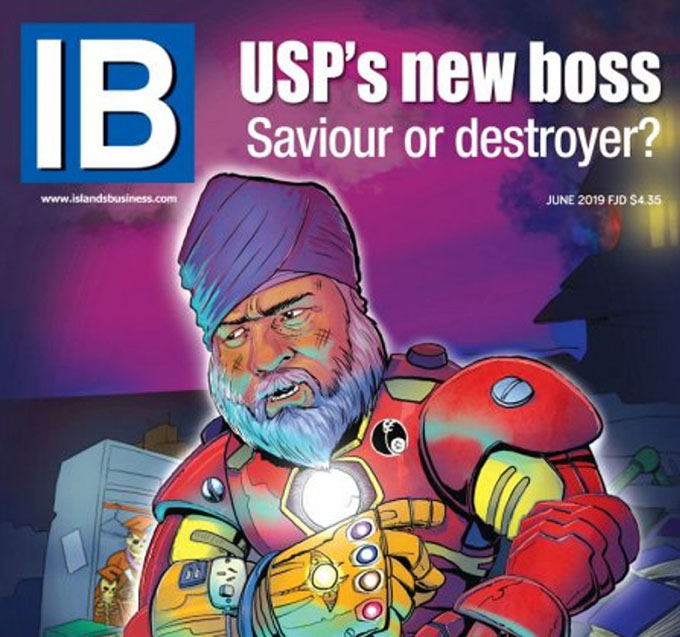

The current vice-chancellor, Professor Pal Ahluwalia, is a reputable academic with an impressive track record as a scholar, as well as an executive experience as deputy vice-chancellor at one of the better universities in the United Kingdom. During his long and distinguished career, he developed specific technical expertise in innovation and research policies which are highly needed in the region.

First principles of university governance

Although there are many different university governance systems for universities, it is generally agreed that academic freedom and a degree of autonomy, like a free and independent press, are essential for a democracy to function properly. There are two channels in which dirty politics, special or personal interests can seep into the texture of universities: one way is by political parties using student politics, and the other way is through the university councils. Often we see a bit of both.

University autonomy is not absolute and has several dimensions, which is why the European University Association, for example, publishes an annual scoreboard on university autonomy.

Organisations like Scholars at Risk monitor threats to individual scholars and academic freedom. In case of serious incidents various human rights reporting mechanisms are used. The price of liberty after all is eternal vigilance, as Thomas Jefferson allegedly said.

In the Pacific, the university system is usually based on the Australian system which favours strong university autonomy independence. This regularly clashes with tendencies of Pacific governments which see university as government departments and want control over all appointments and budgets.

Since universities are statutory organisations and are established by an act of parliament, governments shirk away from abolishing university autonomy de jure, rather than use a number of de facto mechanisms.

As professional international university executives, we add value by bringing our experience from world-class universities in how to get things done, how to access external funding and generate internal funding, and through our professional networks.

This type of know-how and experience is usually hardly available locally.

As vice-chancellor of the PNGUoT, for example, when I enjoyed Council’s support from 2014 to early 2017, I was able to take big strides forward in establishing good governance, effective and efficient management, while at the same time create productive partnerships with industry, mobilise international support, and push the digitalisation, accreditation and academic quality agendas.

When, however, foreign university executives are continually exposed to unwarranted attacks, often fuelled by a deadly mixture of envy, xenophobia, or fear to lose face, we cannot do our jobs. The education of the next generation of Pacific leaders suffers as a result.

The end of university autonomy in PNG

University autonomy in PNG ended during the Peter O’Neill years with the Higher Education Act 2014 which had as the only purpose for the government to gain control over the universities.

Article 109 stipulated the direct appointment of the chancellor and for the vice-chancellor made the government of PNG the appointing authority. Before this Act was gazetted I warned the then Minister of Higher Education, asking him to scrap article 109, to no avail.

As co-chair of the PNG Committee of Vice-chancellors and University Presidents, I was seriously concerned about this type of backsliding.

From 2012 to 2018 there were no less than seven Ministers of Higher Education, which did not help to create good governance.

In 2016, the students of the University of Papua New Guinea in the capital Port Moresby, and the students of the PNGUoT in Lae demanded then Prime Minister Peter O’Neill to submit himself to questioning after credible and serious allegations for corruption had been made.

Peter O’Neill flatly refused and exactly one year ago allowed police to shoot hundreds of rounds peacefully protesting students. An investigation was promised but never occurred, despite my reminder in an interview for ABC Pacific Beat.

At the PNGUoT in Lae the students’ response was immediate but quick thinking by the Metropolitan Superintendent Anthony Wagambie and our mediation, we were able to contain the situation on campus. The threat to the students and the universities was loud and clear.

The prolonged university crisis of 2016, however, resulted in the council being replaced by Peter O’Neill’s appointees and the student representative councils being suspended for an indeterminate period. After the “stolen elections” of 2017, the allegiance of university council members and staff started to shift, since they were all expecting O’Neill to stay on until the next elections in 2022.

Oddly, O’Neill was pushed out of a role in government and resigned as Prime Minister in May 2019. With his Australian friends, O’Neill who likes to boast and dream of becoming the “first Pacific billionaire”, spend most of his time in his own $55 million mansion in Sydney, or at his son’s place, a “modest” $13 million mansion in the same town, according to The Sydney Morning Herald.

When he returned to avoid being thrown out of Parliament last month, he was arrested to respond to allegations for one of the many grand corruption cases and put in a two weeks quarantine. Hopefully, the police are able to produce a proper indictment this time, which can stand up in court to get a conviction.

With O’Neill’s ousting as Prime Minister, university chancellors and council members are now no longer politically protected and feel exposed, which surely in 2021 and 2022 – an election year – will cause more political mayhem in PNG university governance.

Pacific universities case studies

PNG 2013 and 2018: PNG University of Technology (PNGUoT)

In 2013, while in exile in Australia after my first run-in with the Peter O’Neill government, I wrote an article about the importance for universities in Papua New Guinea of establishing good governance and mainstreaming implementation of concrete strategic plans using various proven methods [Schram, 2014].

Later I gave a seminar at the Australia National University where I warned that the PNG university governance reform was failing.

In 2012, I was attracted to the vice-chancellor role of the PNG University of Technology (PNGUoT) because the government had promised to modernise its governance in the wake of the Independent Review of the PNG University System (IRUS, also called the Namaliu-Garnaut Report), and make a considerable investment in the structurally underfunded PNG education system from revenue of the LNG project.

Professor Garnaut, interestingly, was later also declared persona non grata by Peter O’Neill and prevented to enter the country, like so many other foreign professionals during the disastrous O’Neill years.

The review made clear that at the PNGUoT an internationalisation and academic quality agenda had to be pursued vigorously, and the university’s reputation had to be restored with all stakeholders after the official investigation in 2013 led by the late Supreme Court judge Mark Sevua had shown a widespread practice of mismanagement of funds and breaches of due process by the University Council.

In April 2014, a new council had been appointed, and I was called back to lead the university. In 2016, my term was renewed after a performance review. Nevertheless, in 2018 the PNGUoT gave in to political pressure and the witchhunt against the foreigner started again, based on the same baseless allegations as in 2012-13 of not having a doctorate which had already been disproven by an official investigation. Madness.

For those willing to check, here is the official record of my doctorate which I proudly defended on 24 November 1994 at the renowned European University Institute in Florence (Italy), and later published with Cambridge University Press.

My doctorate is explicitly recognised in all EU member states, the USA and Costa Rica.

During the PNGUoT crisis in 2013 as well as in 2018, the support in my regard of Scholars at Risk in New York and the academics at Australian National University, and several journalists knowledgeable about PNG affairs was unfaltering, and I am grateful for that.

Now that in PNG Peter O’Neill has finally been arrested and apparently finally needs to answer the serious and credible allegations, it seems there may be another opportunity for university reform.

His government created fantastic levels of corruption, and the non-resource growth of the economy diminished year upon year between 2012 and 2017.

Each year, the PNG government in order to stay afloat borrowed at unfavourable conditions, massively increasing public debt, and bringing the country close to bankruptcy and threatening debt default.

Needless to say, the promised additional university investment never materialised, and I could only use internal savings to make necessary investments. The PNG Australia relationship meanwhile had been poisoned by the Manus Refugee Camp, where asylum seekers were held unlawfully for years.

PNG 2018: University of Natural Resources and the Environment (UNRE)

In an effort to modernise university leadership in PNG, in 2015 the British professor John Warren was appointed as vice-chancellor of UNRE. VC Warren and I immediately coordinated our strategies in line with the declared government policy following the IRUS (Namaliu/Garnaut) report.

As co-chair of the PNG VC Committee, I attended their graduations and met all their council members.

After working with council to establish accountability and governance processes, we vigorously worked on an academic quality and internationalisation agenda. The advice of other Vice-Chancellors in the Pacific region and Australia to first establish proper financial management, and balance the budget was valuable.

In fact, the savings obtained by stopping wastage, and establishing proper financial control could immediately be invested in improving the learning and working environment on campus, something that both PNGUoT and UNRE desperately needed.

At UNRE the challenge to establish reliable broadband internet remained great, which seriously affected their operations and the ability to attract and retain faculty members.

VC Warren worked with the Academic Board (Senate) and the University Council to establish proper appointment and promotion procedures for academics, as well as robust assessment or exam policies. At this point, VC Warren was attacked, even physically, by members of the AB who felt embarrassed they could not explain how grades were produced.

They went immediately over the head of council and started to spread lies and rumours among members of the Peter O’Neill government, which gullible as they were, were taken for true. As a result, Peter O’Neill decided to appoint a new chancellor, who however escalated the attacks on VC Warren.

Things quickly got really nasty and dangerous.

At this point, the pressure on foreign vice-chancellors in the country mounted to dance to the tunes of the O’Neill regime. First, in April 2018 I was pushed out and despite reaching an agreement with council, I was arrested when trying to return home at Jackson’s International Airport in Port Moresby.

The police which presented no evidence and was acting directly on orders of Peter O’Neill through the ousted Pro-Chancellor Ralph Saulep, managed to keep me hostage unlawfully retaining my passport for one month, after which a judge in the National Court granted me permission to go home.

The whole sad episode was described on ANU’s Development Policy blog, and several articles in The Times Higher Education (1 and 2) and The Australian (1 and 2) and other international press in Italy and the UK, thus tarnishing the reputation of the country and its universities.

Less than one month later the other foreign vice-chancellor, John Warren, was threatened and had to flee for his life.

At the end of 2017, University Council members had shifted their alliance after O’Neill successfully stole the 2017 elections, with full support from the Australian government at the time.

Australian Minister of Foreign Affairs Julie Bishop, for instance, declared the 2017 “successful” before they were even finished, and while serious elections violence was ongoing in several highland provinces.

Fiji 2020: The University of the South Pacific (USP)

The crisis situation at USP is still ongoing, and I know the political background and personalities more superficially. As co-chair of the Pacific Islands University Network, which we set up in 2012, I visited USP regularly which hosted the secretariat of the network.

When he took over last year, vice-chancellor Professor Pal Ahluwalia asked council to be consulted over senior appointments, so as to be able to appoint his own independent executive team. He was denied this common courtesy.

Subsequently, he reported to council about lack of accountability and various breaches of university rules involving the appointment or renewal of various university administrators. This seems to have set off the current crisis with the Executive Committee (EC) of council suspending him for supposed misconduct without, however, having any primary evidence.

Rather, all evidence presented points to mismanagement by members of the previous administration and current council.

In his report to the Executive Committe, VC Pal writes the following:

“EC receives this report and takes urgent action both internally and externally. It is incumbent upon USP to be critically aware of its fiduciary and legal duties and responsibilities, especially in regards to donors and authorities that demand transparent and accountable management in the disbursement of public funds. It is further recommended that EC take corrective actions with the highest priority accorded to these matters.”

He then describes a long list of irregular appointments, which in some cases led to excessive expenses, and in all cases have constrained his ability to lead the university effectively.

Fortunately, support for “VC Pal” is strong and solid, and we hope that this becomes clear to all the council members and they lift his suspension after the next council meeting. The episode however in a regional perspective leaves a bad taste of corruption and xenophobia. The threat is that national dirty politics capture a regional university, which then goes down in political infighting.

Let us hope it will not go any further, and VC Pal can continue his good and important work. As a regional university, for 40 percent funded by mainly New Zealand and Australia, it would be essential Australia joins New Zealand, Samoa and Nauru in their wish to put this episode behind them, and stop the baseless attacks on USP’s VC.

Making a public statement however may not be enough.

Final remarks

Since 2018, both PNG universities plunged into an ever-deepening crisis. Since the student representative councils were rendered powerless or suspended, the students’ voice was effectively silenced. Both universities are now unable to retain honest and professional staff, with the Papua New Guineans being the first to leave, followed by all expatriate faculty members with other career options, and work experience at world-class universities.

All others are desperate to leave, but often unsuccessful.

PNG universities may have a second chance if their council is renewed and the council members appointed by Peter O’Neill lose their seats. It is imperative the students’ voice and university autonomy is restored, by revoking article 109 of the 2014 Higher Education Act, which only purpose was to establish strong political control.

The University of South Pacific can well emerge stronger from the present crisis, if it is short and the commission doing the independent investigation is indeed independent and given a broad mandate.

This is what saved my position in 2013 when Judge Sevua’s team established there was nothing wrong with my appointment or actions, and rather focused its attention on the mismanagement overseen by the previous university council and management.

VC Pal Ahluwalia today indicated he would cooperate fully with the investigation, which is the right thing to do. He has no other option.

It would be important, however, the main stakeholders and in particular Australian government make their support for good governance and VC Pal is heard, before this institution too succumbs to political infighting as has happened in PNG.

References

Schram, Albert (2014). University Governance and Transparency in the PNG University System, Journal of Pacific Studies, Volume 34, pp. 77-90 (ISSN 1011-3029). Retrieved from https://www.usp.ac.fj/fileadmin/files/Institutes/jps/Volumes/Volume_34_No_1_2014/Full_Text_-_University_governance_and_transparency_in_the_PNG_higher_education_system.pdf

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz