Analysis by Keith Rankin.

Recently I have published charts showing how people born around 1960 are already placing huge burdens on New Zealand’s healthcare system (Death Frequencies in Aotearoa New Zealand, by Birth Year, 26 Sep 2024) and how big falls in age-specific death rates have plateaued since 2010, and may now be reversing upwards (Death Rates of Older Working Males in Aotearoa New Zealand, from the late 1970s, 17 Oct 2024).

Here I look at decennial increases in total deaths by ‘generation’, where each generation is a ten-year birth cohort centred on a zero year. Featured generations are the ‘lucky generation’ (b. circa. 1940), post-war baby-boomers (b. circa. 1950), generation Jones (b. circa. 1960), generation X (b. circa. 1970) and generation Y (b. circa. 1980).

In Table 1 above we see that in 2020, 109% more people born around 1970 died than in 2010. The main reason for the increase is that these ‘Gen-X’ people were ten years older in 2020 than in 2010. Secondary reasons could relate to the net-immigration between those years for that age cohort, or could relate to the underlying health attributes of generation-X.

(Note that the ‘+’ in the labels arises because, due to data limitations, the definition of the generations used varies slightly for each year. Thus, for 2021, Gen-X is 1966-1976.)

We see that all of the followed generations show marked increases in the increases of deaths as we progress from 2020 to 2022, with the younger age cohorts showing increased increases in 2023 as well. Generation-X is highlighted as having the biggest increases in each of these four years: 2020, 2021, 2023, 2024. This suggests underlying health issues in this generation, or greater increases in net immigration for Gen-X (compared to say Gen-J or Gen-Y), or both.

On the matter of Gen-X net immigration, we note that immigrants must undergo health checks, so it’s likely that the death rates of Gen-X immigrants since 2010 are lower than the death rates of Gen-X non-immigrants. So it’s looking like there are significantly problematic health issues being experienced by Gen-X Aotearoans.

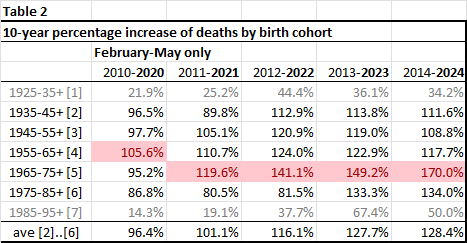

Table 2 focusses on just February to May data. These are the months in which death numbers are generally lowest. Older people tend to die more in winter, and younger people in summer. These are mainly autumn data. We also note that Table 2 allows us to access 2024 mortality data.

This is more worrying for Gen-X, because the data show higher rates of death increase from 2022, with an especially problematic number – a 170% increase in deaths – for 2024. These data definitely suggest there’s an underlying health problem, especially for that generation. The problem may be in two parts: underlying health status (eg incidence of chronic illnesses), and increased inadequacy of healthcare (including inability to access life-saving drugs).

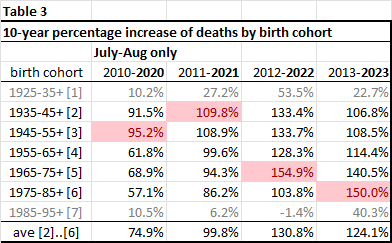

Table 3 focusses on July and August only, the two main months for deaths attributable to respiratory infectious diseases. As we would expect, the older generations come out ‘tops’ in 2020 and 2021. But in 2022, the year the pandemic hit in New Zealand, it’s Gen-X again which has copped the biggest increases in deaths from infectious causes. Further, in 2023, it’s the younger generations – Gen-Y as well as Gen-X – that are showing the greatest increases in winter deaths. (Lack of access to Covid19 boosters might be part of the problem here.)

So, while yesterday’s charts might have showed that life-expectancy improvements have bottomed out after 2010, these table suggest that very recent mortality data is showing definite signs that life expectancies are starting to fall, with Gen-X – born around 1970 – taking the lead in this new development.

From the point of view of funding the healthcare system, not only is the aging of the population not being properly accounted for, but also substantial swathes of the bulging generations (generations J and X) are seemingly less healthy. We remember that deaths are only the ‘tip’ of the disease ‘iceberg’; mortality increases indicate underlying morbidity increases, and it is morbidity that places the greatest demands on healthcare.

(Is there a ‘sound’ fiscal argument for expanded access to euthanasia in the coming decades?!)

*******

Data is from Statistics New Zealand, Births and deaths: Year ended June 2024.

Keith Rankin (keith at rankin dot nz), trained as an economic historian, is a retired lecturer in Economics and Statistics. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand.