Analysis by Keith Rankin.

Recessions in the last Ten Years: New Zealand and Japan

Tomorrow we will see the latest Gross Domestic Product (GDP) data for New Zealand. It’s worth looking today, however, at what the situation is before that data release (with its revisions as well as new data). And in context by comparing New Zealand with a country with different demographic circumstances.

First, the journalistic definition of a recession is two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth; this is normally taken to be overall GDP, not GDP per person in the growing or declining population.

An alternative definition is to compare GDP in the latest quarter with GDP in the same quarter of the previous year. By this Y-to-Y definition, any negative number is a recession. However, for New Zealand, the highest quarter for GDP in today’s available data is the September 2022 number (1.325 billion dollars; not shown in table). Therefore, each quarter of 2023 has a lower GDP number than September 2022. Thus, by this definition, all of 2023 should be classed as in recession.

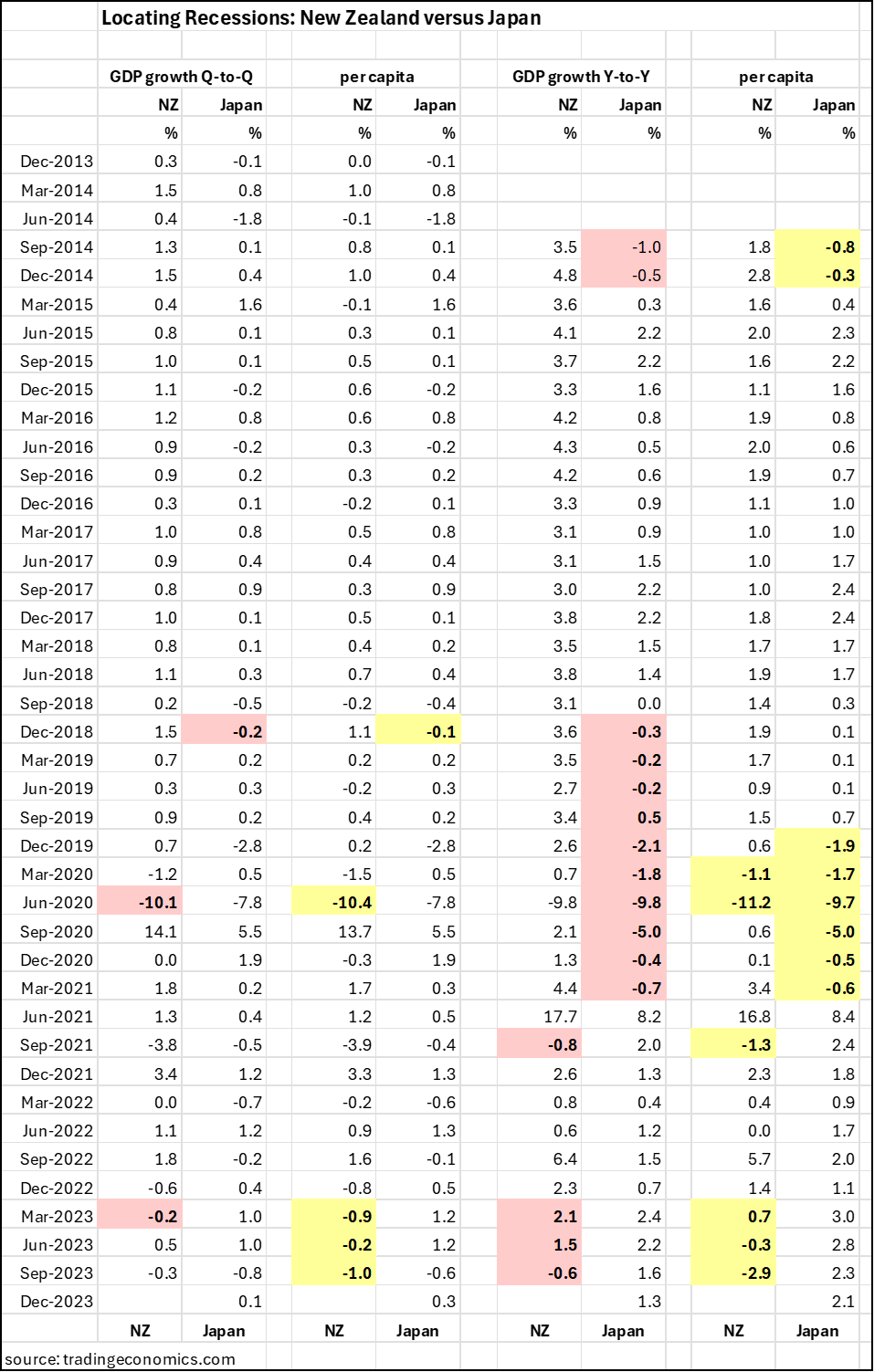

The table below highlights recessions in New Zealand and Japan by both definitions, and then adds per capita recessions. (Per capita – ie population adjusted – recessions are highlighted in yellow.)

Under the commonly used criterion, New Zealand was in a technical recession in the first quarter of 2023, and in the June quarter of 2020. The 2020 recession is clearly related to the Covid19 disruptions. (And Japan was in recession only at the end of 2018.) When allowing for population changes, New Zealand under this measure has been in a recession for all of 2023.

When applying the alternative measure of recession, we see again that New Zealand has been in recession for all of 2023 for which we have data today. Japan turns out to have been in a long recession during 2019 and 2020.

What is also important to note is that, despite overall slower growth in the last ten years, Japan has shown itself to have had a much more vigorous economy than New Zealand in 2023.

I will follow this up tomorrow with some explanations for the superior performance of Japan after 2020.

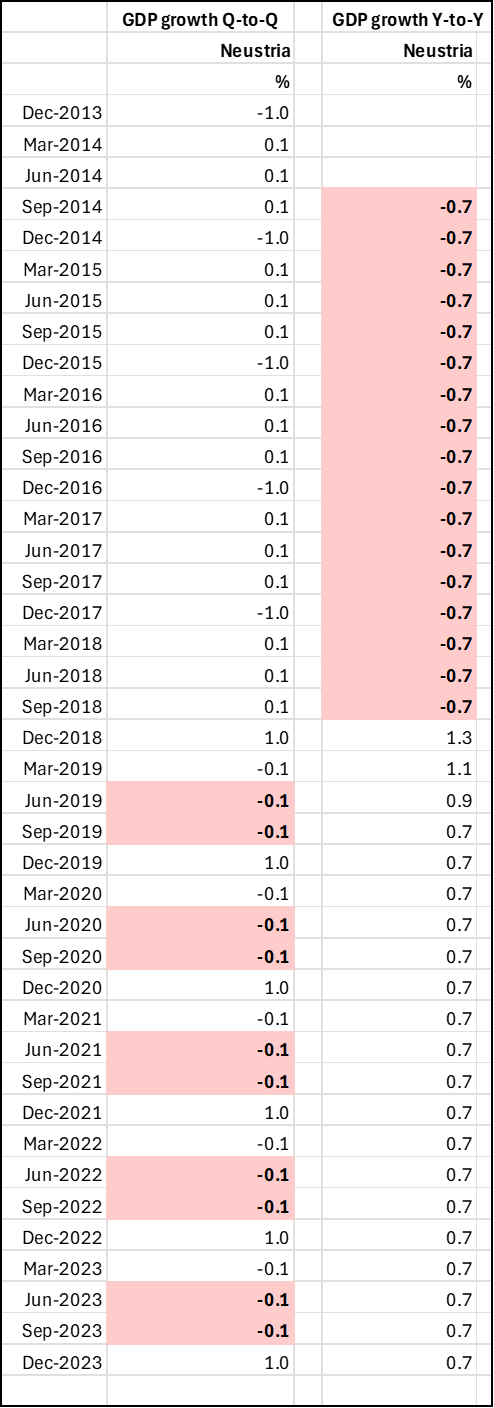

But I will end this by considering the imaginary country of Neustria.

In Neustria, the general pattern was falling GDP from 2013 to 2018. And the general pattern from 2019 to 2023 was rising GDP.

The alternative definition of recession shows this correctly; Neustria was in recession from 2013 to 2018. But the popular measure our media and some academics use shows recessions only (and persistently) in the growth period from 2019 to 2023.

This last table shows the substantial shortcomings of our popular definition of recession. It suggests that the alternative measure suggested is superior to the popular measure. This reaffirms the reality that the New Zealand economy has been in recession through most if not all of 2023. And that’s the reality New Zealand businesses were facing last year, and are still facing this year.

*******

Keith Rankin (keith at rankin dot nz), trained as an economic historian, is a retired lecturer in Economics and Statistics. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand.