Analysis. by Keith Rankin.

On 26 October I wrote about New Zealand’s exceptional financial model, showing it to take a similar (though non-fraudulent) form to a Ponzi Scheme (The Ponzi financial model and New Zealand’s monetary policy). And I showed how this kind of financial behaviour by a nation-state could help to stabilise a world economy when some other national economies pursued a strongly contrasting model. I call the two models the ‘ponzi model’ (with New Zealand as exemplar) and the ‘mercantilist model’ (with Denmark and Netherlands as twenty-first century exemplars).

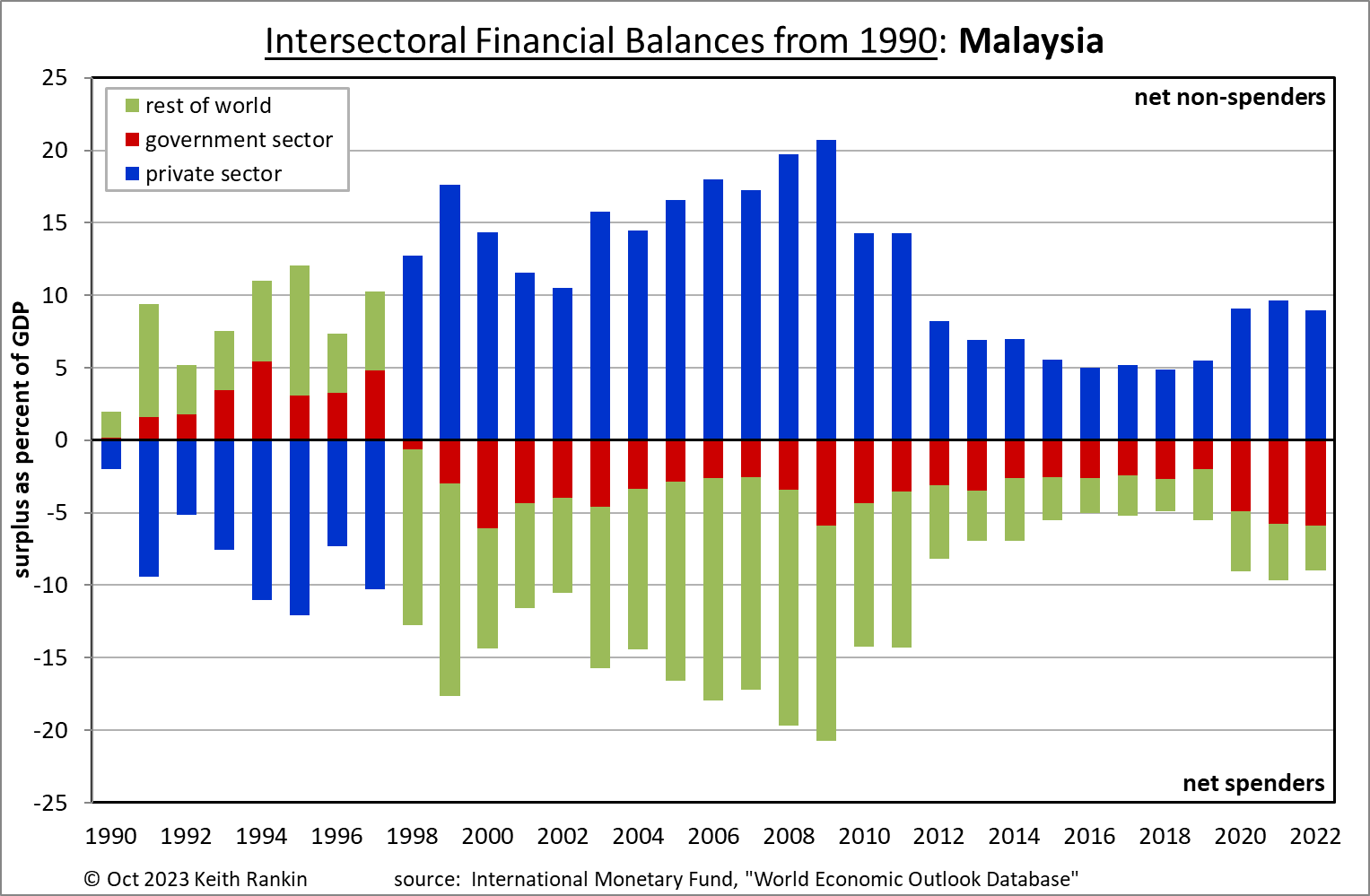

Malaysia, here, is a country which switched from the excesses of one model to the excesses of the other, before reaching a neutral position after the 2012 Eurozone crisis.

In the Malaysia chart, we see Malaysia adopting the ponzi model around 1990. The telltale signature is the persistent amounts of foreign money (green) going into Malaysia’s private sector (blue), with the government creaming the resulting money-go-round, running fiscal surpluses (red).

Malaysia was one of the countries which precipitated the Asian financial crisis late in 1997. Having to pay back much of the debt incurred in the 1990 to 1997 ponzi period, we see a massive switch to private sector saving paying back much of the foreign debt incurred and then saving by accruing foreign credits.

For 14 years, Malaysia kept up an extreme form of the mercantilist model, which has foreign deficits as its main feature (which means current account surpluses). This 1998 to 2011 signature is one of high saving (blue), exports exceeding imports (green), and the export of material living standards (green) to countries like New Zealand. Fiscal policy (indicated by red) followed closely to global norms; annual government deficits of about 4% of GDP.

This pattern continued in Malaysia until 2012 when mercantilism became the collective financial policy of the Eurozone countries. After 2012 the East Asian trade surpluses got smaller, as these countries increasingly looked to domestic markets to keep their economies growing. (The last three years, of course, is the Covid19 pandemic, a period of increased government deficits.)

(Malaysia, by the way, has an interest rate of 3%, and which has not gone above 3.25% in the last 10 years. Its inflation peaked at four percent in 2022, and is now 1.9%. Its government debt is 60% of GDP, nearly twice as high as New Zealand’s. Its neutral post-2012 financial model is delivering for Malaysia.)

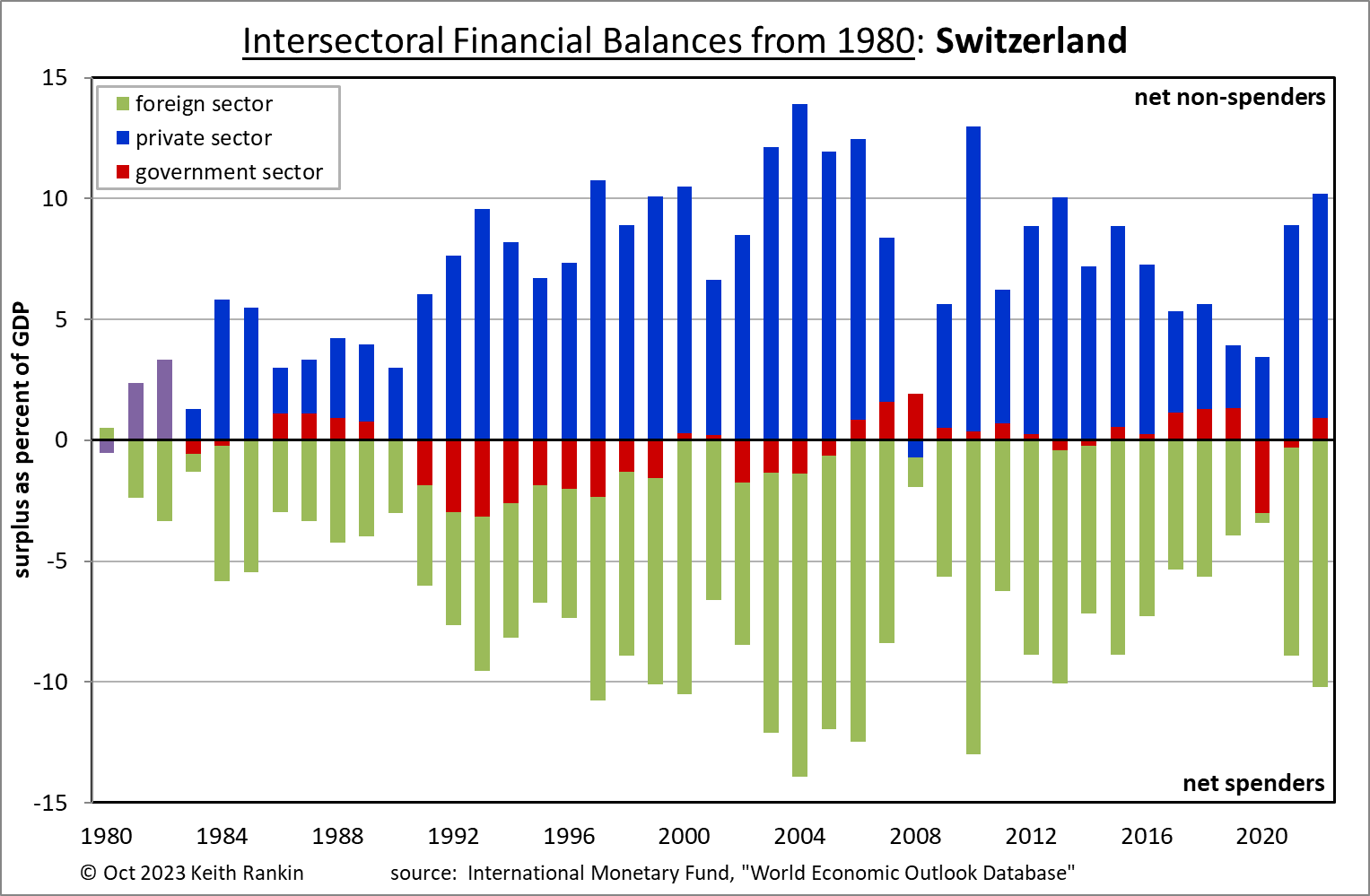

Switzerland is exceptional in that it is the world financial centre, par excellence, and is the headquarter country of global corporates and world governance agencies (including much of the United Nations).

Thus, Switzerland makes large global profits which are deployed all over the world, hence the persistently strong savings (blue) and foreign deployment of those savings (green). While it has the look of a mercantilist country (like Netherlands), its special circumstances with respect to the global economy mean that this is by circumstance rather than by design.

Fiscal policy is passive in Switzerland. It does not make any fetish about the desirability of governments running financial surpluses. It’s government debt, much greater than New Zealand’s in dollar terms, is 41% of GDP, compared to New Zealand’s 36%.

Switzerland’s interest rate has been minus 0.75% for most of the last ten years. For half of that time, its inflation rate has also been negative. For much of the time its interest rate was similar to its inflation rate; in the late-2010s its inflation rate was positive, though under one percent. Its current interest rate is 1.75% and its inflation rate is 1.7%. The main reason for its low inflation has been its low interest rate. Unlike New Zealand, Switzerland has not created a domestic cost of living crisis, because it did not raise its domestic interest rates.

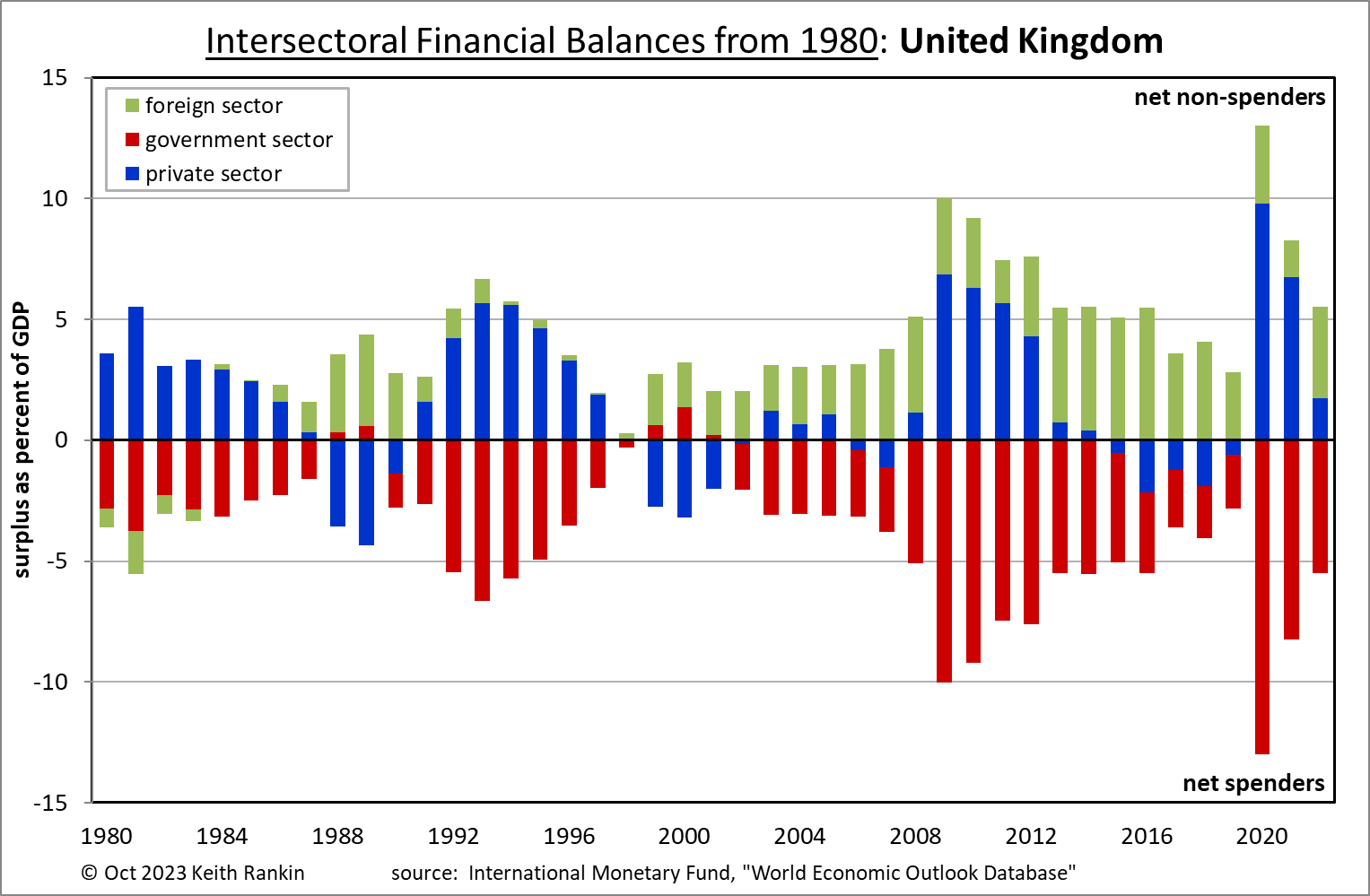

The United Kingdom shows aspects of New Zealand’s ponzi model; in particular it is a recipient and spender or foreign savings, especially this century. However, United Kingdom no longer pretends that fiscal (government) surpluses are necessary. Although David Cameron’s government (2010-2017) did misguidedly try for a large dose of government austerity, known there as ‘fiscal consolidation’. The United Kingdom is also notable in that it does not accrue large private debts in the way New Zealand does.

The United Kingdom is exceptional in that not all that country’s economy is covered by its national statistics. The United Kingdom economy includes a range of realm countries – such as Jersey, Guernsey, Isle of Man, Cayman Islands, Gibraltar – some of which are tax havens with economies with which contain a disproportionate part of the United Kingdom’s financial activity. So the United Kingdom’s chart is in fact incomplete; invisibly offset by these other countries which do not keep comprehensive statistics, and which most likely all have financial balances like Switzerland.

The United Kingdom has interest rates and inflation rates similar to New Zealand. Its current interest rate is now 5.25% and inflation rate is 6.7%. As with New Zealand, it has a hawkish monetary policy (anti-inflationary in dogma if not in reality); an excessive readiness to raise interest rates (with, as in New Zealand, unstated additional motives for this policy) created and perpetuated its cost-of-living crisis.

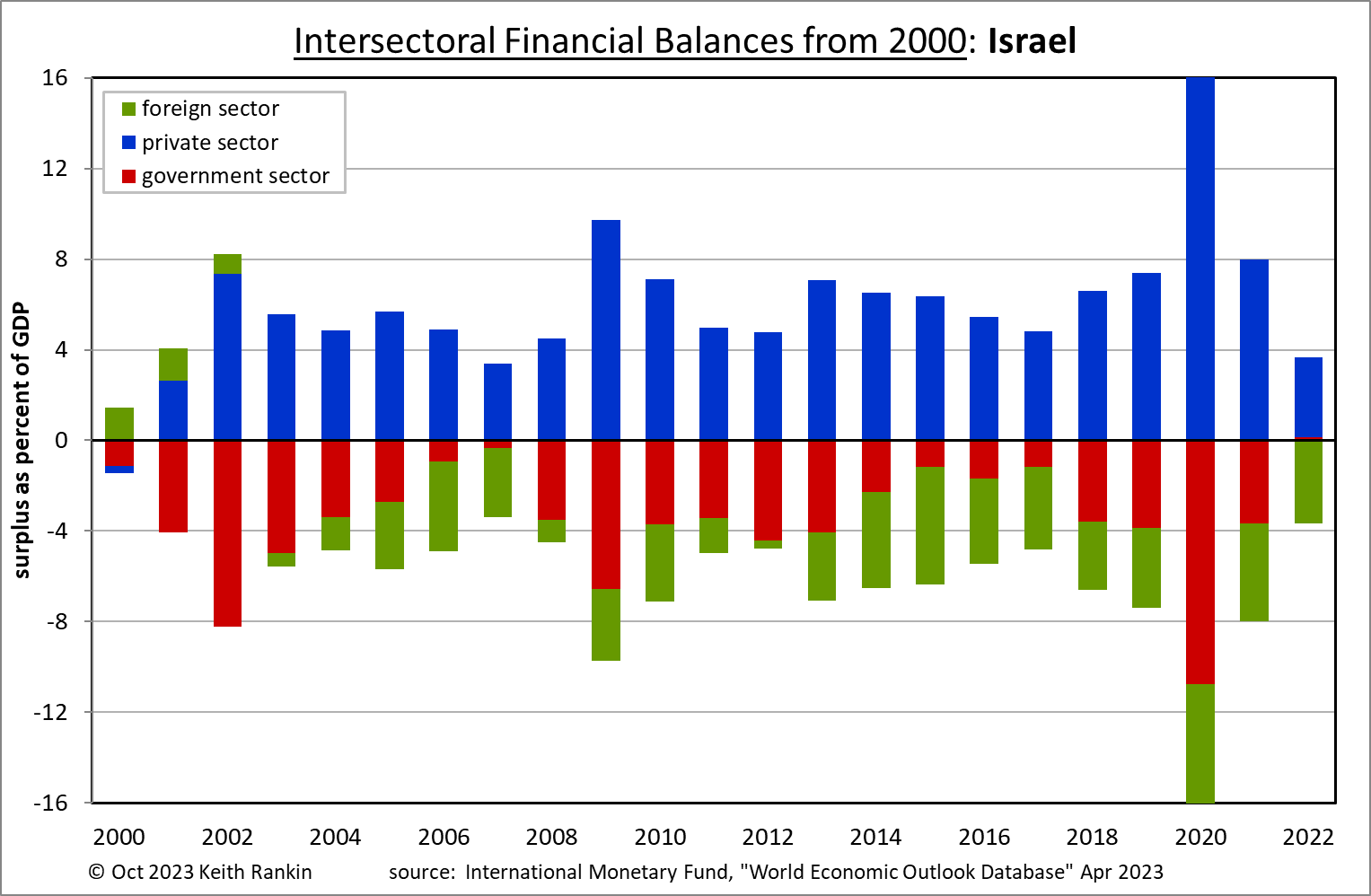

Finally, Israel is a mercantilist nation with a mercantilist mindset. It’s a financially conservative country, with private sector surpluses and savings deployed to other parts of the world. But you will see that it has substantial government deficits. In this respect it is like the United States, and of course (like the USA) the red in Israel’s chart shouts ‘defence’, or at least a very well-funded military sector. While Israel is a net exporter – hence the green on the lower portion of its chart – it is of course a recipient of foreign aid in the form of grants (mainly from the United States) rather than loans.

Israel’s inflation peaked at just over five percent and the interest rate is now 3.8%. From 2014 to 2021 Israel’s inflation varied between minus 1.5% and plus 1.5%. In that time interest rates were between 0.1% and 0.2%. Israel did not have an inflation problem, despite its high levels of government spending. Its government debt is 61% of GDP, twice New Zealand’s. (Government spending, per se, is not the cause of cost-of-living crises; although government spending without outcomes can be a contributing factor to inflation.)

Nobody would accuse Israel of unsound finance. But it does have very different monetary and fiscal policy agendas than New Zealand. And Israel is closer to the world’s norms than is New Zealand. For Israel’s first-class citizens – the majority of the population in its less-disputed territories, along with a minority of the population of occupied Palestine – there is markedly less inequality.

*******

Keith Rankin (keith at rankin dot nz), trained as an economic historian, is a retired lecturer in Economics and Statistics. He lives in Auckland, New Zealand.