Analysis by Keith Rankin.

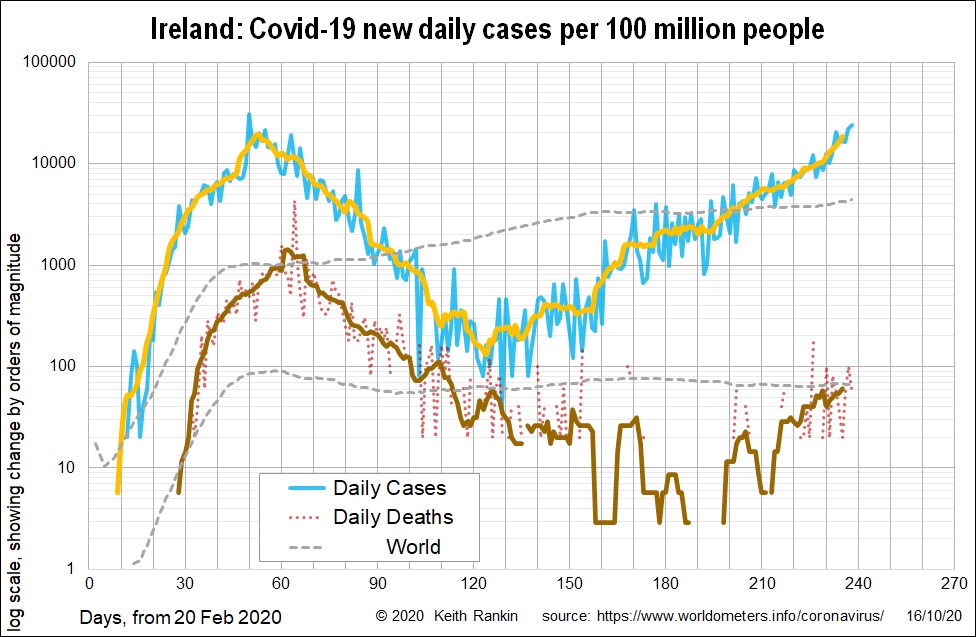

This week’s first chart looks at a familiar island country with the same population as New Zealand. The chart shows daily cases at the top, and daily deaths at the bottom; and it includes world averages for comparison.

The most striking recent feature on the Ireland chart is the straight-line (exponential) growth of cases from late-June to mid-October. While the growth is not as rapid as in March, it is more persistent and more consistent. While this exponential pattern cannot continue forever, with the onset of winter in Ireland, this trend line could project forward for another month. 100,000 daily cases per 100 million people would be equivalent to one percent of the population testing positive over a ten-day period. That would be like 50,000 positive cases in New Zealand over ten days; fortunately, New Zealand has fewer than 2,000 known cases in total.

While death rates are much lower in Ireland now than they were in April and May, they are nevertheless at the world average and are likely to get much higher for the remainder of 2020. Latest death rates per capita can be seen to be about one percent of case rates 15 days prior. The true case fatality rate is probably 0.5 percent, meaning that Ireland’s recent undiagnosed Covid19 cases would be about the same as the recent diagnosed numbers. By way of contrast, at the time of the April peak of the previous Covid19 wave in Ireland, the true number of cases was probably ten times higher than the then known number of cases; that is, an April peak of 200,000 actual cases per 100 million people.

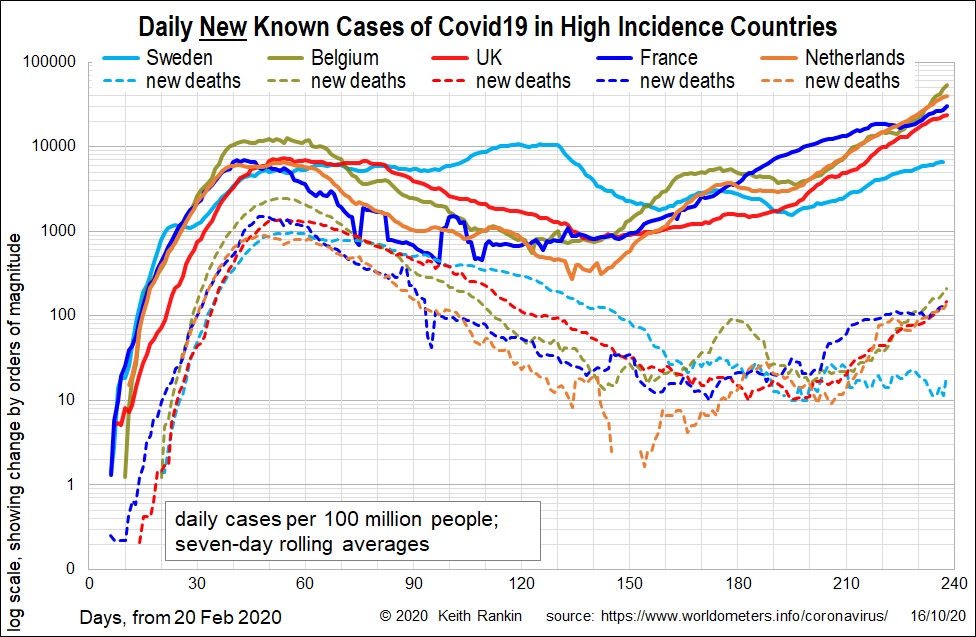

While Netherlands and Belgium are worst for new cases, France and the United Kingdom are not far behind. Netherlands is of particular note, because it essentially followed the Sweden model of minimal restrictions, though with less honesty than Sweden in its published death tolls. Belgium’s published statistics were the worst of all these countries, and still are. There is no sign at present that Belgium or Netherlands have gained anything like ‘herd immunity’, despite their high early infection rates.

Sweden is looking better now, but only in comparison to these other egregious cases. Sweden’s cases are still on the rise; and its main protection is its much lower population density, and its cultural propensity towards a degree of physical distancing as its norm.

As in the case of Ireland, if you look at the latest death rates, and compare them with the case rates 15 days earlier, we find a (known) case fatality rate of about one percent. (Lower for Sweden, which is most likely now finding a greater proportion of its actual cases, thanks to much higher recent testing rates.)

Covid19 is basically out of control in the featured countries here. While death rates may be ameliorated by better knowledge of effective treatments, these countries certainly look to be in for a grim winter. And the numbers of Covid19 survivors still suffering from long-term after-effects in 2021 can be expected to be one of the biggest media stories next year.