Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Holly Thorpe, Associate Professor in Sociology of Sport and Physical Culture, University of Waikato

The World Surfing League recently became the first US-based global sporting league to offer equal pay to male and female competitors.

In a Facebook post, the league announced that women surfers will receive equal pay at all events from 2019. In the world of surfing – a sport and culture long dominated by men — this is a monumental development.

A range of issues, including women’s activism, international sport policy change, female leadership and male allies, have led to this decision. The factors might be unique to surfing but they illustrate the complex ways in which significant gender changes come about in some sports.

Read more: Should women athletes earn the same as men? The science says they work as hard

Women’s activism in surfing

Since the beginning of wave-riding in ancient Hawaii, women have been active participants in the cultural practice of surfing. In the contemporary context, however, the hyper-masculinity celebrated in surfing culture has meant that women had to develop new strategies.

Cori Schumacher, former world champion and self-proclaimed surf feminist and activist, described how from the late 1970s to the mid-1990s, female surfers were marginalised, with minimal sponsorship or prize money, and largely invisible in the surf media.

Over the past decade, women’s positions in the sport have undergone radical changes. Professional female surfers gained the respect of their male peers and of viewers around the world. The visibility appears to be having important trickle-down effects, with the numbers of recreational female surfers continuing to grow.

The World Surfing League (WSL) organises professional surfing internationally. In 2016 it instigated a move to address the gender pay balance. The men’s purse was US$551,000 (split between 36 surfers) and the women’s purse US$275,500 (divided among 18 surfers).

Women have been riding waves since the beginnings in ancient Hawaii. Damien Poullenot EPA, CC BY-NDProfessional female surfers have been advocating for decades for their rights, including equal pay, access to events, visibility and sponsorship. Their struggles and successes have ebbed and flowed with industry changes, and alongside broader social trends. Women outside the professional sport have also contributed through campaigns against the sexualisation of female surfers.

The Committee for Equity in Women’s Surfing has worked tirelessly to fight for gender equity. It drove the movement in California for women to gain access and equal pay to the infamous big wave event at Mavericks.

When they failed to persuade the WSL, they lobbied the California Coastal Commission, the state permit-granting agency tied to the Mavericks event, arguing that gender-based discrimination was against the law. Key members of the commission were convinced that this constituted inequity.

Read more: More money may be pouring into women’s sport, but there’s still a dearth of female coaches

Olympics and gender equity policy

Surfing will be making its Olympic debut in the Tokyo 2020 summer games, and this also has an important effect. Much of the public commentary on the inclusion of surfing, alongside skateboarding and sport climbing, has focused on these sports’ appeal to younger audiences. But promoting women’s participation and involvement in sport is also central to the IOC’s modernisation agenda. Key aspirations include achieving 50% female participation.

Our research suggests that by setting targets for gender inclusion for the international federations, the IOC is exerting a regulatory pressure with impact on the structures and decision-making in recruitment of staff and committee representatives.

Surfing at the Olympics will be governed by the International Surfing Association (ISA), with the support of the WSL. The ISA actively promotes itself as being committed to “best practice”. Along with implementing some gender diversity across their various boards and committees, their flagship international surfing competitions are the central way to demonstrate this commitment.

In May, the ISA announced that it would offer equal competition slots for women and men in the 2018 World Surfing Games and the World Junior Surfing Championship. However, it has not been equitable across the board. In the 2018 Adaptive Surfing World Championship team competition, women’s events scores are only weighted at 50% of the men’s scores. 2017 World Champion adaptive surfer Dani Burt was so irked that she wrote a protest letter, arguing that:

The announcement of 50% points is not progress, it’s a reminder that in the eyes of the association and the world, women are considered less than men.

Women’s leadership, men’s support

Our research has revealed that new opportunities for women in (or close to) leadership positions in surfing have also played an important role in initiating further changes towards gender equity. It was suggested that the WSL’s recent efforts to promote elite women was driven by Natasha Ziff, wife of non-surfing billionaire Dirk Ziff, a key WSL investor and interim chief executive in 2016 and 2017.

Women’s prize money and the number of events have increased dramatically. The industry is starting to recognise the abilities and market potential of female surfers, but Ziff’s influence seems to have accelerated the change.

In July 2017, the WSL appointed a new female chief executive, Sophie Goldschmidt. She was not a surf industry insider, but a seasoned sports industry executive who recently took 15th place on the Forbes list of the most powerful women in international sports. Although initially arguing that pay in professional surfing was equitable, in interviews she has repeatedly declared her commitment to gender equity, and describes this latest announcement for equal pay as “an important statement … celebrating what is happening in society”.

Earlier this year, in an attempt to reduce the widespread sexualisation of female surfers, the WSL released a warning against photographers zooming in on bikini bottoms. Goldschmidt was instrumental in this and other initiatives, including the launch of an international marketing campaign that will highlight the women’s tour.

Male athletes can play an important role in supporting female surfers’ struggles for equity. Sergio Dionisio AAP, CC BY-NDA complex picture

Our research also illustrates the important roles that men have played in supporting women’s struggles for equity. These male allies range from those in positions of power in sport organisations, industry and media, to professional surfers. For example, 11-time world champion Kelly Slater has repeatedly acknowledged the long history of phenomenal female surfers and their right to equal pay.

Researchers Johanna Adriaanse and Inge Claringbould have suggested that influential men can become change agents when they challenge gender stereotypes within their organisational structures. They advocate that closer collaboration and support between men and women can help, but that the men who continue to control much of the resources need to be central.

Our research included comparisons of surfing and skateboarding. We have seen that men in powerful positions certainly play an important role in helping to create gender change. However, how they respond to the challenge of gender equity is informed by the gender relations within their sporting cultures.

Despite these important signs of change in surfing, many working in the industry continue to embrace practices that emphasise hegemonic masculinity, sexualising and objectifying womens’ bodies, and the exclusion of women as athletes and leaders. For any significant and sustained cultural change to occur, gender equality will need to be addressed across all practices – from national and international federations to everyday interactions among recreational participants.

The gender equity policy changes in surfing show that sporting feminism matters. Progress is often the result of activism, advocacy, and strategic alliances.

– ref. Women’s surfing riding wave towards gender equity – Go to Source]]>

Local news report on the chaos in Palu.

Local news report on the chaos in Palu.

Earthquake survivors in Palu, Central Sulawesi, crowd Mutiara Sis Al Jufri Airport in Palu in a desperate attempt to leave the devastated area on Monday. Image: Andi Hajramurni/Jakarta Post

Earthquake survivors in Palu, Central Sulawesi, crowd Mutiara Sis Al Jufri Airport in Palu in a desperate attempt to leave the devastated area on Monday. Image: Andi Hajramurni/Jakarta Post

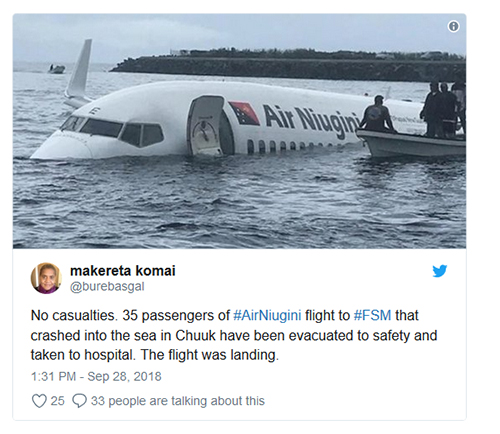

Pacnews editor Makareta Komai’s tweet on the crash landing.

Pacnews editor Makareta Komai’s tweet on the crash landing.