Editor’s Note: Here below is a list of the main issues currently under discussion in New Zealand and links to media coverage. You can sign up to NZ Politics Daily as well as New Zealand Political Roundup columns for free here.

Today’s content

National Party, ACT

Charlie Mitchell and Laura Walters (Stuff): Christopher Luxon’s property gains soar as National promises to tackle housing crisis

Jenna Lynch (Newshub): National leader Christopher Luxon unaware his $7m Remuera home increased in value by $2.3m over one year

Herald: New National leader Chris Luxon owns seven properties – two funded by taxpayers

Zane Small (Newshub): National leader Christopher Luxon with 7 properties ‘wouldn’t want to see house prices fall dramatically’

—————

Matthew Hooton (Patreon): Bridgesnomics (paywalled)

Chris Trotter (Daily Blog): The Fellowship Of The Upper Room

Brigitte Morten (NBR): Labour should be worried by Luxon’s leadership tale (paywalled)

Josh Van Veen (Democracy Project): Bridges isn’t the one

Josie Pagani (Stuff): Actually, Leader of the Opposition is a great job

Herald: National Party reset around Christopher Luxon needs to work

Thomas Coughlan (Herald): Abortion u-turn, housing pivot: Chris Luxon’s first day as National Party leader

Henry Cooke (Stuff): Christopher Luxon says he will vote for safe zones outside abortion clinics at second reading

Russell Palmer (RNZ): Willis promises to be balancing force as National’s new deputy leader

1 News: National’s new leaders sit down with Jessica Mutch McKay (video)

Thomas Coughlan (Herald): Christopher Luxon’s rise – and the tricky question of faith in politics (paywalled)

Thomas Manch (Stuff): New National leader Christopher Luxon and the big issues, where he stands

Newstalk ZB: Christopher Luxon: New National leader on his vision, key issues and moving forward (audio)

Newstalk ZB: Nicola Willis: National’s liberal and conservative wings came together yesterday (audio)

Jamie Ensor (Newshub): Christopher Luxon praised for performance after leadership election, listening to groups Government ‘has lost’

Mike Hosking (Newstalk ZB): Time will tell, but Luxon is off to a good start

Kate Hawkesby (Newstalk ZB): I’ve changed my mind on Christopher Luxon

Pete Burdon (Media Training): Chris Luxon’s Media Interview Skills

Zane Small (Newshub): Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has no plans to change approach with Christopher Luxon as National leader

Glenn McConnell (Stuff): The National Party opted for predictable Christopher Luxon over changemaker Shane Reti

Mike Houlahan (ODT): Southern MPs positive on Luxon; Woodhouse set to lose role

Herald: Winston Peters says Judith Collins displayed terrible judgment, queries Simon Bridges’ business skills

Jamie Ensor (Newshub): Christopher Luxon offers to wear cowboy hat during interview, help The AM Show hosts water-ski

—————

Peter Dunne: Can ACT’s dream run continue?

Marc Daalder (Newsroom): Friend or foe – Seymour welcomes Luxon challenge

Public Service

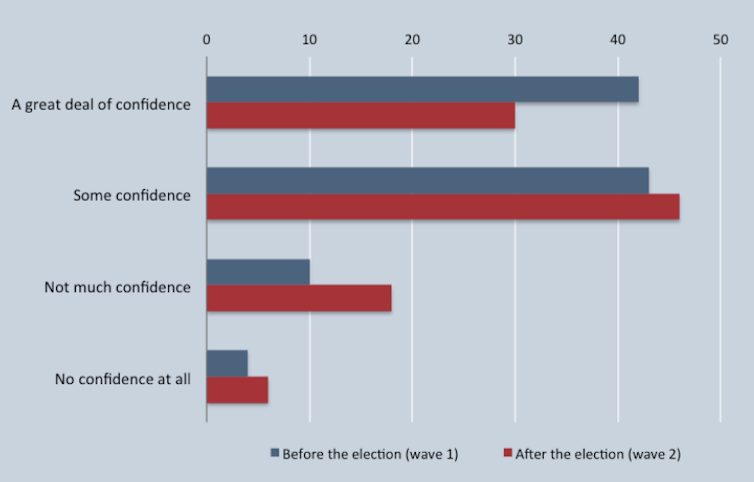

Barbara Allen and James Gluck (The Conversation): Can New Zealanders be confident about ethics in public service?

Oliver Lewis (BusinessDesk): Procurement gets political: Gumboot Friday

Oliver Lewis (BusinessDesk): Beyond price: ‘better balance’ for government procurement

Traffic light system, Auckland border opening

Northland Age (Herald): Northland iwi leaders get backing from DHBs to keep border closed to unvaxxed

Sam Olley (RNZ): Iwi chairs, DHB bosses have ‘grave concerns’ Covid will spread into Northland this summer

1 News: Holidaymakers won’t be barred from Bay of Islands over summer

Whanganui Chronicle: Whanganui iwi leader asks holidaymakers not to visit this summer

Maxine Jacobs (Stuff): ‘Don’t come if you’re not vaccinated’ — Whakatū iwi urge holidaymakers to be responsible

Lorna Thornber (Stuff): Should we travel to areas with low vaccination rates this summer?

Ireland Hendry-Tennent (Newshub): Chris Hipkins says iwi shouldn’t set up roadblocks to stop tourists

Lloyd Burr (Magic): Good intentions doesn’t give you the power to police the roads, and stop and check people

Mike Houlahan (ODT): Elimination first option, SDHB says

William Terite (Herald): Rural hospitals anxious as Aucklanders set to flee city

Mark Quinlivan (Newshub): The restaurants refusing to take part in traffic light system and check vaccine certificates

Monika Barton (Newshub): Jacinda Ardern reveals she may have to uninvite wedding guests under COVID-19 traffic light system, leaving planning to Clarke Gayford

Herald: Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern on wedding plans: ‘You’d have to ask Clarke’

Lillian Hanly (1 News): Waitangi Treaty Grounds to be crowd free at 2022 events

Jo Moir (Newsroom): Waitangi commemorations cancelled under Covid’s shadow

Denise Piper (Stuff): Waitangi Day celebrations at Treaty Grounds canned for 2022

RNZ: Waitangi Day events for 2022 cancelled

Stuff: Suzuki Series and Cemetery Circuit cancelled

Dubby Henry (Herald): Afterschool care, holiday programmes can reopen under red light

James Halpin (Stuff): Anti-vaccine mandate pastor says church will comply with traffic light rules

Economy, business, government subsidies

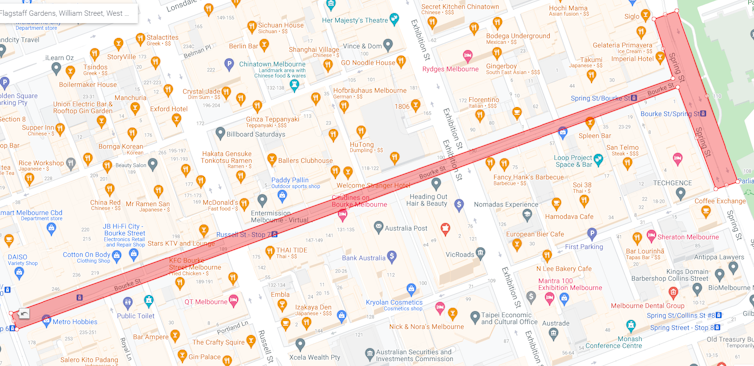

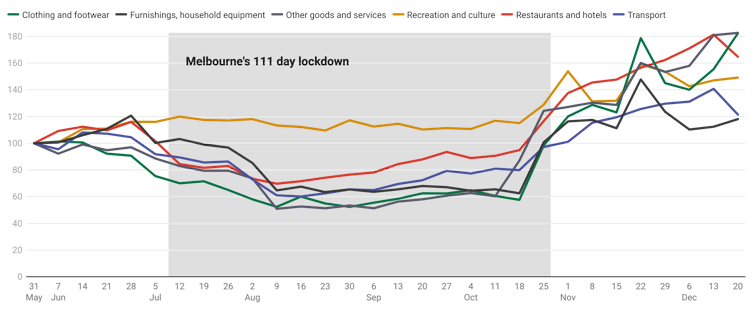

RNZ: Millions being spent to ‘reactivate economic activity, enhance wellbeing’ in Auckland

1 News: Aucklanders to get attractions vouchers to ‘spark’ recovery

Ireland Hendry-Tennent (Newshub): Chris Hipkins defends hospitality being left out of Govt’s $37.5 million Auckland stimulus package

RNZ: ‘Auckland is being punished’ as government pulls wage subsidy – Hospitality NZ

Lincoln Tan (Herald): Hospo misses out on $37m Government voucher package to reactivate Auckland

1 News: Auckland hospitality ‘crushed’ at voucher scheme exclusion

Michael Neilson (Herald): 100,000 vouchers for Aucklanders to reactivate city as lockdown ends

Adam Jacobson (Stuff): Prime Minister unveils $37m Auckland recovery fund, including 100k free tickets

Herald: Auckland’s arts sector welcomes move to traffic light system – but few shows to hit the stage before Christmas

Herald: $37m package includes explore Auckland vouchers over summer

Shawn McAvinue (ODT): Sector asks for further govt support

RNZ: Government expenses and deficit surge as it grapples with Covid-19 pandemic

Tom Pullar-Strecker (Stuff): Covid puts further $1b dent in Government coffers in October

RNZ: Travelling in a pandemic: ‘Plan for what insurance won’t cover’ – Insurance Council

Evan Harding and Amanda Cropp (Stuff): Backpacking industry on verge of collapse; Invercargill hostel adjusts to survive

Courtney White (ODT): Workers nervous about rules

Jared Morgan (ODT): Covid complications test for hospitality

—————

Kim Moodie (RNZ): Employers lagging behind on support for menopausal women

Daniel Dunkley (Stuff): Omicron Covid-19 variant highlights Reserve Bank’s perilous path

Cameron Bagrie (BusinessDesk): Taming the beast that’s inflation (paywalled)

ODT: Beware the scourge of inflation

Toby Allen (Interest): What’s in store for housing, interest rates and the Kiwi dollar in 2022?

Anne Gibson (Herald): American film, TV giant Warner Bros wins consent to buy Auckland land

RNZ: The Detail: The MLM scheme making money from money-traders

Megan McNay (Herald): How to make a difference

Govt management of Delta outbreak

RNZ: Covid-19 wrap: Child vaccines in early 2022, Omicron in MIQ ‘inevitable’

Mike Hosking (Herald): Damning report on Covid-19 response tells us what we already know (paywalled)

Derek Cheng (Herald): How Auckland avoided the hundreds of deaths in Sydney and Melbourne (paywalled)

Mandatory vaccination, vaccine pass, rules

William Hewett (Newshub): Chris Hipkins blames overseas vaxxed Kiwis ‘supplying their information at the last minute’ for vaccine pass delays

Lincoln Tan (Herald): Fully vaccinated Kiwis struggling to get vaccine pass two days from traffic lights system

Newstalk ZB: Chris Hipkins: People vaccinated overseas may wait up to 14 days to get Vaccine Passes

Jo Lines-MacKenzie, Jonathan Guildford and Esther Ashby-Coventry (Stuff): Elderly, disabled struggling with tech requirements of vaccine passes

Chris Keall (Herald): Pharmacy a life-saver; MoH updates on overloaded help line (paywalled)

James Ting-Edwards (Stuff): Digital Identity in New Zealand: Technical choices have human impacts

Brianna Mcilraith (Stuff): Lone Star New Lynn goes against vaccine mandate by advertising for waiting staff on No Jab Jobs website

Kirsty Wynn (Herald): The cafes and restaurants refusing to open doors in support of unvaxxed

Herald: Gisborne’s Tatapouri Bay campsite to allow unvaccinated visitors this summer

Esther Taunton (Stuff): VTNZ to require proof of vaccination from learner drivers before practical test

Tamsyn Parker (Herald): ANZ to require branch workers to be vaccinated or take rapid antigen test. But what about customers?

Ellen O’Dwyer (Stuff): Schools no longer required to keep register of vaccinated students

Daisy Hudson (ODT): Uni proposes vaccine mandate for all

ODT: Dunedin only one of southern councils insisting on passports

Logan Savory (Stuff): No vaccine proof needed at most Invercargill City Council facilities

Rachael Comer (Stuff): Vaccine passes required at libraries and pools in Timaru district

ODT: Most Invercargill public facilities won’t require pass

Brent Melville (BusinessDesk): The unvaxxed: councils brace for 100s of dismissals (paywalled)

MIQ, home isolation

Amelia Wade (Newshub): Climate Change Minister James Shaw skipped COVID-19 managed isolation MIQ and joined self-isolation trial

Richard Harman (Poliitk): Government maintains tough clamp on migration

Tom Hunt (Stuff): No plans to replace Wellington MIQ despite calls for closure by Ombusdman

Robin Martin (RNZ): Shortage of oximeters worries iwi healthcare provider

Cases, demographics

Jamie Morton (Herald): Modeller answers five key questions about case trends

RNZ: Hospitalisation rate has dropped, Director-General of Health Ashley Bloomfield says

Hannah Martin (Stuff): Hospitalisation, ICU cases ‘levelled off’ in Auckland outbreak

Rachel Sadler (Newshub): ‘Emerging cluster’ at Bay of Plenty School, 70 pct of hospitalised COVID patients unvaccinated

Anna Whyte (1 News): Latest Nelson Covid case not linked to initial ones

RNZ: Two Nelson schools close after staff test positive for Covid-19

Vaccine rollout

Jake McKee (RNZ): Officials urged to move faster on vaccinating children aged 5-11

1 News: Vaccine rollout for children likely to begin in January

Bridie Witton (Stuff): Vaccinations for children aged 5 to 11 due to begin from January

Florence Kerr (Stuff): Kids and the Covid-19 vaccine

RNZ: ‘Confident’ Māori vaccination rates will hit target – Dr Rawiri Jansen

1 News: 15 out of 20 DHBs at 90% first dose jab rate

Hannah Martin (Stuff): Fewer than 24 hours left to get both doses in time for Christmas

Monika Barton (Newshub): Siouxsie Wiles and David Seymour among stars of ‘Vax The Nation’ music video from Dr Joel Rindelaub and Randa

Anna Leask (Herald): Christchurch psychologists team up to combat needle anxiety, boost vaccination rates

Anna Leask (Herald): Coroner investigating whether Dunedin man’s death connected to vaccine days earlier

Omicron variant

RNZ: Chris Hipkins: ‘Inevitable’ Omicron variant will show up in MIQ

Brittney Deguara (Stuff): ‘Inevitable’ Omicron will arrive in MIQ, Chris Hipkins says

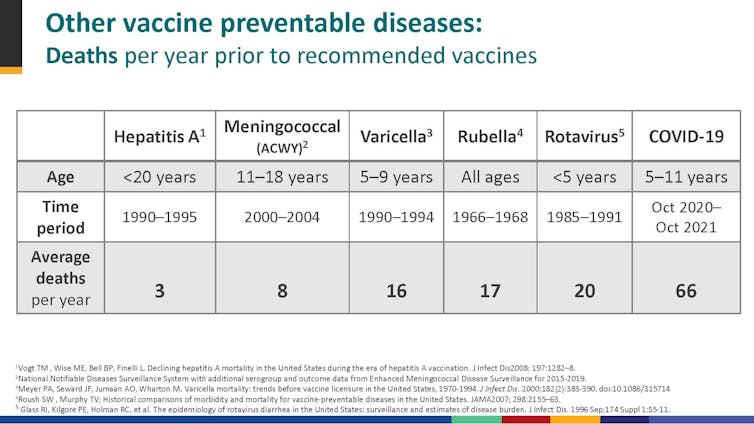

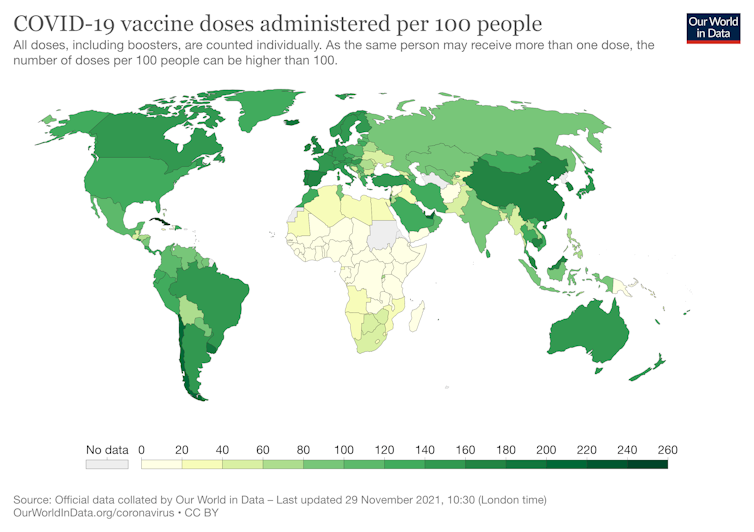

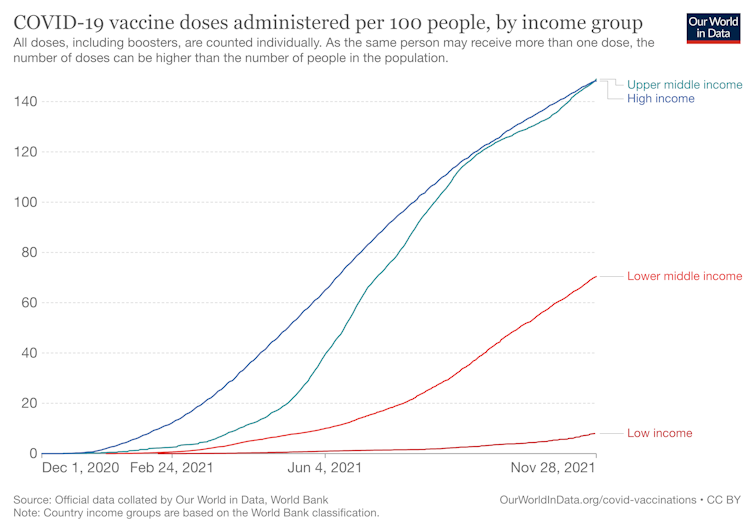

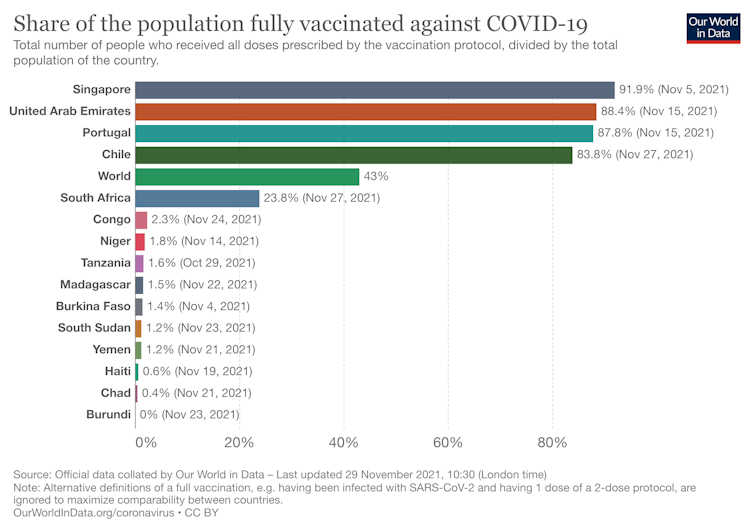

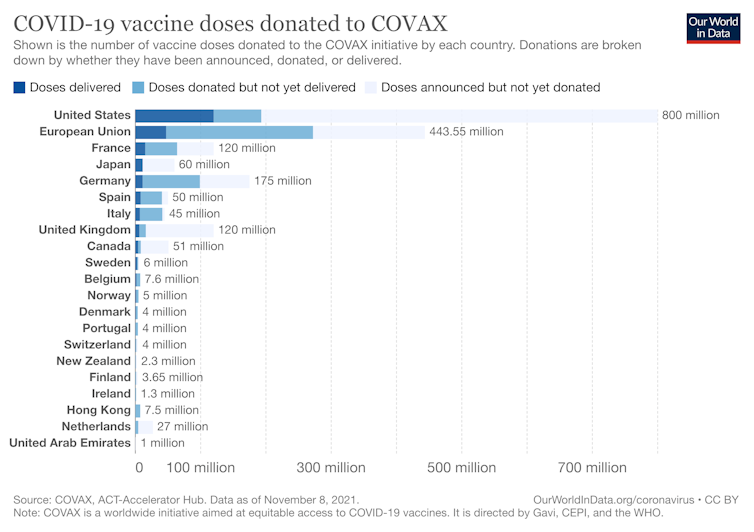

James Ussher (Newsroom): Vaccine equity must be a global priority

Gwynne Dyer (Stuff): Digital peasants and the ignorant rich

Housing

Jonathan Milne (Newsroom): Snap decision time: National’s new leader prises open 3-storey housing pact

Henry Cooke (Stuff): Housing advocates urge National to stay the course on bipartisan deal to force councils to allow more homes

Geraden Cann (Stuff): Mega Landlords: 48 per cent rise in homes owned by trustees ‘suggests tax avoidance’

BusinessDesk: Is housing market FOMO finally evaporating?

Susan Edmunds (Stuff): ASB: House prices will fall next year

Tamsyn Parker (Herald): Mortgage rates have shot up but deposit rates are still low. Are banks ripping savers off?

Katrina Shanks (Stuff): Want a mortgage? Get ready for extra scrutiny

Sophie Trigger (Herald): Wellington house prices: New Zealand’s first state home is now worth more than $1m

Joel MacManus (Stuff): Wellington City Council to consider rent freeze for social housing tenants

Kirsty Frame (RNZ): Wellington City Council social housing tenants may soon get help with rent

Sahiban Hyde (Hawkes Bay Today/Herald): A&P Society member calls for Government help to save Hawke’s Bay showgrounds, housing proposal stays on table (paywalled)

Miriam Bell (Stuff): Canterbury home consent numbers beat earthquake rebuild record

Health

Herald: Ministry of Health survey: Covid mental health toll, smoking down, obesity up

Cushla Norman (1 News): Record number of Kiwis gave up cigarettes in the past year

Natalie Akoorie (Local Democracy Reporting): Waikato DHB cyberattack: Cancer hub out of action in chaotic aftermath

Nikki Preston (Herald): MoH investigation into Waikato DHB cyber attack still months away

Tess McClure (Guardian): New Zealand to enshrine protections for pill testing in ‘world first’

Mike Houlahan (ODT): Medical physicists to walk off the job

Luling Lin (Herald): Nitrates in water and risks to babies – what the evidence shows (paywalled)

Local government, Three Waters

Arena Williams and Stuart Smith (Stuff): Government reforms will make water safer and cheaper for us all, so why the protests?

Andrew Bayly (Herald): The strategic value of water (paywalled)

Phil Pennington (RNZ): MBIE officials meet with Auckland Council over delays to hospital building consents

Moana Ellis (Local Democracy Reporting): Rangitīkei District Council sticks with 11 seats, including two new Māori seats

Logan Savory (Stuff): Council governance group meetings to now be held in public

Craig Ashworth (Local Democracy Reporting): Iwi will be first in line to buy council land

Riley Kennedy (ODT): DCC companies report profits despite pandemic

Susan Botting (Local Democracy Reporting): Whangārei: District’s new residential property value increases ‘mind boggling’ – resident

Felix Desmarais (Stuff): Rotorua waste plan: Kerbside organic waste collection, charges for rubbish dumpers floated

Matthew Littlewood (Stuff): Timaru District Council’s $1.5m grant tipped Scott Base bid in PrimePort’s favour

Auckland Council climate tax

Simon Wilson (Herald): Hooray for Auckland Council’s billion-dollar climate plan (paywalled)

Jordan Bond (RNZ): Goff’s climate levy a sly way to raise rates – ACT

Bernard Orsman (Herald): Auckland mayor Phil Goff announces climate change tax among proposed 5.9 per cent rates increase

Heather du Plessis-Allan (Newstalk ZB): Auckland climate tax a potential PR failure

RNZ: Auckland mayor proposes to charge households a climate levy

Tess McClure (Guardian): Auckland homeowners to pay $1.10 a week under ‘climate tax’ plan to green the city

Environment, conservation, Climate Change

Jamie Gray (Herald): NZ carbon prices hit record $68/unit at auction, post COP26 (paywalled)

RNZ: Dunedin City Council wants plan that addresses coastal system ‘as a whole’

Benn Bathgate (Stuff): Diving into mātauranga Māori to find an 800-year-old solution for 70-year-old problem

Debbie Jamieson (Stuff): Government to spend $850,000 on cycle trail maintenance

David Williams (Newsroom): DoC caves on national park walkway ‘extravagance’

Nina Hall, Charles Lawrie, and Sahar Priano (Stuff): Climate activism has gone digital, disruptive, and is facing up to racism within the movement

Georgina Campbell (Herald): Predator Free Wellington wants to use ‘inhumane’ trap to catch elusive rats

Primary industries, Groundswell protests

Rachael Kelly (Stuff): Prime Minister may release information about Groundswell NZ

Tina Morrison (Stuff): Fonterra expected to pay highest milk price since it was formed 20 years ago

Maja Burry (RNZ): Report funded to inform councils on farmland use and forestry

Employment

Charlotte Lockhart (Stuff): The ‘great resignation’ creates fertile ground to demand flexible working

Chris Tobin (Stuff): Timaru port workers may strike for two days

Tamsyn Parker (Herald): Gender equality not happening at the expense of men, ANZ CEO says (paywalled)

Police, crime

Tom Pullar-Strecker (Stuff): ‘Open secret’ NZ has offensive cyber capability, security firm says

RNZ: GCSB offers new cyber defence service to private security providers

Phil Pennington (RNZ): High Court rules against police in unprecedented proceeds-of-crime case

RNZ: Checkpoint: Self-styled justice reformer knew he could not be charging to help prisoners – Corrections

Foreign Affairs

George Block (Stuff): Solomon Islands unrest: Defence Force, police to deploy for weeks-long mission

1 News: NZDF, police being sent to Solomon Islands amid unrest

Scott Palmer (Newshub): New Zealand sending Defence Force, Police to Solomon Islands after days of violence and rioting

Herald: Solomon Islands crisis: New Zealand sends troops and police to assist with humanitarian crisis looming

RNZ: New Zealand forces deployed to Solomon Islands

Agence France-Presse (Guardian): Solomon Islands unrest: New Zealand to send dozens of peacekeepers

Immigration

Anuja Nadkarni (Newsroom): Immigration plugs hole after unlawfully misinterpreting its policy

Hanna McCallum Brianna Mcilraith Tina Morrison (Stuff): Website crashes as applications open for fast-track migrant resident visas

Michael Neilson (Herald): Immigration residency visa website for one-off fast track applications crashes

Transport

Courtney Winter (Herald): Canterbury’s road toll highest in New Zealand

Kate Green (Stuff): Free public transport for Wellingtonians at Christmas, New Year

Damien O’Carroll (Stuff): VTNZ and Waka Kotahi brace for a surge in driver licencing tests under traffic light system

Tara Shaskey (Stuff): Waka Kotahi to propose highway speed limit of 80kmph – transport committee members

Steven Walton (Stuff): Christchurch bus services to be scaled back during weekdays due to driver shortage

Sapeer Mayron (Stuff): Auckland mother concerned Ministry’s school transport scheme bursts Covid bubbles

Energy

Andrew Owen (Stuff): Massive Taranaki wind turbine application gets resource consent

Liz McDonald (Stuff): $100m ‘world-leading’ solar plant will be 50 times bigger than any in New Zealand

Herald: Solar farm to be built at Christchurch Airport

Infrastructure

Ross Copland (Herald): We need to be in for the long term (paywalled)

Stephen Douglas, Michele Villa, James Viray and Greg Carli (Herald): Infrastructure: Radical collaboration

Graham Skellern (Herald): Infrastructure: Price of a world-class infrastructure system (paywalled)

Fran O’Sullivan (Herald): Infrastructure: Time to make the big calls (paywalled)

Fran O’Sullivan (Herald): Infrastructure: Political buy-in is central to success of long-term plans (paywalled)

Fran O’Sullivan (Herald): Infrastructure: Water – Dealing with a long-standing deficit (paywalled)

Tim McCready (Herald): Infrastructure: Credit for green credentials

Tim McCready (Herald): Infrastructure: Compensation for businesses impacted by construction (paywalled)

David Greig (Herald): Infrastructure: KiwiRail’s infrastructure problem (paywalled)

Other

Laura James (1 News): Abuse towards disabled Kiwis reaches ‘epidemic proportions’

1 News: Kiwis, Australians most trusting of scientists – survey

Roger Partridge (Herald): Roadblock on literacy’s pathway to prosperity (paywalled)

Stuff Editorial: Swamped coroners mean anguished families and less insight

Mark Story (Hawkes Bay Today/Herald): Nash’s freedom camping rules half-cocked (paywalled)

RNZ: RNZ launches new platform for rangatahi