The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Fabrizio Carmignani, Professor, Griffith Business School, Griffith University

The evidence on the ground is very clear. The Trump tax cuts have led to stronger investment, stronger growth, lower unemployment rate and higher wages.

– Minister for Finance Mathias Cormann, interview on RN Breakfast, August 13, 2018

After two years of debate and months of intense negotiation, the government’s proposal to cut the corporate tax rate from 30% to 25% for companies with turnover of more than A$50 million was voted down in the Senate.

But while the government’s attempts to pass tax cuts in Australia were not fruitful, tax reform remains a significant international issue.

In arguing for a tax reduction for big business, Minister for Finance Mathias Cormann pointed to economic outcomes in the United States, where corporate tax rates were cut from 35% to 21% in January this year.

“If you look at the economic data in the US in the second quarter, of course post the Trump tax cuts, the US is recording in excess of 4% growth on an annualised basis, the unemployment rate now has a ‘three’ in front of it, and wages growth is the strongest it’s been in a very long time,” Cormann said.

“Massive, massive capital investment has been returned to the United States.”

Is that right? And if yes, are the tax cuts to thank? Let’s take a closer look.

Checking the source

In response to The Conversation’s request for sources and comment, a spokesperson for Cormann provided GDP and capital investment data from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis, employment data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, a Bloomberg article, and a January 2018 World Economic Outlook from the International Monetary Fund.

You can read the full response from Cormann’s office here.

Verdict

Minister for Finance Mathias Cormann’s statement that corporate tax cuts in the US had “led to stronger investment, stronger growth, lower unemployment rate and higher wages” is not supported by evidence.

Cormann pointed to US economic data from the second quarter of 2018 (shortly after the US corporate tax cuts were enacted) to support his statement.

Cormann correctly quoted the figures about GDP growth and the unemployment rate. His statement on wage growth is debatable, and there are qualifications to be made about his interpretation of the capital investment data.

But the simple observation that some US economic indicators improved in the second quarter of 2018 does not imply that those improvements were caused by the tax cuts.

Even if causation could be established, one quarter of data tells us very little about the effect of tax reform. It takes time for companies and workers to adjust to changed taxation environments. These adjustments happen progressively over time, and this can lead to significant differences in the short term and long term responses.

It’s worth noting that the improvement in economic conditions in the US started in mid-2016, around 18 months before the tax reform.

The fundamental issues with the claim

Can we really look to US economic data from the second quarter of 2018 to support (or for that matter, reject) the argument that corporate tax cuts would benefit Australia?

My answer is no, for two reasons.

There is not evidence of causation

The simple observation that some US economic indicators improved in the second quarter of 2018 (after the introduction of the corporate tax cuts) does not imply that those improvements were caused by the tax cuts.

Several other factors will determine economic dynamics in any given quarter. A sophisticated statistical analysis based on a longer string of data after the second quarter of 2018 would be needed to determine the causal contribution of corporate tax cuts.

The assessment of causality is further complicated by the fact that there is a lag effect of corporate tax cuts on the economy.

It takes time for companies and workers to adjust to changed taxation environments. These adjustments happen progressively over time, and this can lead to significant differences in the short term and long term responses.

It’s also important to note that the improvement in US economic conditions started in mid-2016, around 18 months before the tax reform.

One quarter of data is not enough

Even if we neglected the causality issue, data from the second quarter of 2018 only gives us a limited idea of the very short term effects of the corporate tax cuts.

When it comes to tax reform, long term effects are what really matters. The important difference between short term and long term effects is evident from the preliminary economic projections published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in August 2018.

According to the authors of the IMF working paper, the US corporate tax cuts are projected to have a modest impact on long term growth, but will also cause an increase in the US federal debt to GDP ratio by approximately five percentage points by 2023.

Therefore, the corporate tax cuts may, in the end, fail to sustain long term growth, and make it harder to reduce government deficits and debt.

Rather than focusing on what happened in the second quarter of 2018 in the US, those debating corporate tax cuts should look at the economic theory and evidence drawn from countries where tax reforms have been implemented for a longer period of time (for example, Canada and Germany).

In general, this body of research does not provide any solid theoretical or empirical evidence backing the argument that corporate tax cuts will lead to a more prosperous economy.

A closer look at the economic figures

As outlined above, we cannot say that the Trump tax cuts “led to” the economic outcomes quoted by Cormann. But we can take a look at the numbers, for interest’s sake.

Cormann pointed to four macroeconomic benchmarks:

US GDP growth

Cormann said the US is “recording in excess of 4% growth on an annualised basis”.

Based on GDP data from US Bureau of Economic Analysis, and with the growth rate calculated as annualised change over the previous quarter, Cormann was correct: GDP growth hit 4.1% in the second quarter of 2018.

The GDP growth rate can also be calculated as the change compared to the same quarter of the previous year.

On that measure, the growth rate was 2.8%, compared to 2.1% in the second quarter of 2017, following a steady increase from 1.3% in the second quarter of 2016.

US unemployment rate

In July 2018, the US unemployment rate was 3.9%, as Cormann correctly stated.

The chart below shows both the employment rate at the end of each quarter (for example, June 2018 for the second quarter of 2018) and the average rate across the three months in each quarter.

US wages growth

To support his statement about US wages growth, Cormann pointed to a Bloomberg article which drew on data from the US Bureau of Labour and Statistics Employment Cost Index. In the second quarter of 2018, this particular index did record its highest growth since mid-2008.

However, measures of “wages” differ depending on which parts of employees’ salaries are included, and which are excluded.

Another, and perhaps more useful, definition of wages is employees’ average hourly earnings, also reported in the table.

The picture emerging from this measure quite different. These figures show that employees’ average hourly earnings actually fell in the year to the second quarter of 2018.

This doesn’t support the conclusion that wage growth in the second quarter of 2018 was the “strongest it’s been in a very long time”.

US capital investment

We can measure capital investment by looking at Nonresidential Gross Private Domestic Investment data, sourced from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis. These figures show a pick up in investment in the first and, to a lesser extent, second quarters of 2018.

These figures are not, however, necessarily evidence of “massive capital investment” being “returned” to the US, as Cormann stated.

The figures Cormann quoted in his response to The Conversation measure capital expenditure on commercial real estate, factories, tools and machineries in the US – not where the investment comes from.

The term “nonresidential” doesn’t refer to foreign investment, but to investments in commercial (rather than residential) assets.

The chart below, based on data from US Bureau of Economic analysis, shows there was an increase in capital investment in the first quarter of 2018 (when the tax cuts were implemented).

Again, this follows a trend of increases in capital investment, with peaks and troughs, since the first quarter of 2016.

The continuation of an existing trend

Overall, the data paint a rather favourable picture for the US in the second quarter of 2018.

However, it also seems that these macroeconomic indicators began to improve in mid-2016. This is particularly the case for GDP growth and unemployment.

Therefore, the positive outlook for the US in the second quarter seems to be the continuation of a positive cyclical phase that started before the enactment of the corporate tax cuts. – Fabrizio Carmignani

Blind review

I concur with the verdict.

Senator Cormann’s assertion that the growth in business investment and wages and the decline in unemployment observed in the US over the first half of this year can be attributed, either wholly or in part, to the Trump administration’s corporate tax cuts is not supported by the evidence.

As this FactCheck points out, all of these trends were under way well before the corporate tax cuts took effect, and one or two quarters worth of data is not sufficient to establish that the tax cuts have made any significant or sustained change to those trends.

I disagree that average hourly earnings is a ‘better’ measure of US wages growth than the employment cost index (for the same reasons that most Australian economists regard the ABS wage price index as a better measure of Australian wages growth than average weekly earnings).

But that doesn’t undermine the conclusion that the gradual upward trend in US wages growth was well established before the Trump administration’s corporate tax cuts came into effect, and owes far more to the gradual tightening in the US labour market (which has been underway for a long time before those tax cuts came into effect) than it does to those tax cuts.

Indeed, over the first two quarters of 2018, the employment cost index rose by just 0.1 of a percentage point more than it did over the first two quarters of 2017, which is hardly compelling evidence of a significant impact of the corporate tax cuts.

It is worth noting that one-fifth of the 21% annualised rate of growth in US real private non-residential fixed investment over the first half of this year was due to a 156% (annualised) increase in investment in “mining exploration, shafts and wells”.

This category that accounts for less than 4% of the level of private non-residential fixed investment, and the spurt in this category of business investment would have owed far more to the rise in oil prices since the middle of last year than it would have to the cut in corporate tax rates.

Finally, it is also worth noting that the one component of the Trump administration’s corporate tax reforms which the IMF and others have acknowledged would likely have some temporary positive impact on business investment – the immediate expensing for tax purposes of capital expenditures incurred before 2023 (what we in Australia call an ‘instant asset write off’) – isn’t part of the measures which Senator Cormann had been asking the Senate to pass. –Saul Eslake

The Conversation FactCheck is accredited by the International Fact-Checking Network.

The Conversation’s FactCheck unit was the first fact-checking team in Australia and one of the first worldwide to be accredited by the International Fact-Checking Network, an alliance of fact-checkers hosted at the Poynter Institute in the US. Read more here.

Have you seen a “fact” worth checking? The Conversation’s FactCheck asks academic experts to test claims and see how true they are. We then ask a second academic to review an anonymous copy of the article. You can request a check at checkit@theconversation.edu.au. Please include the statement you would like us to check, the date it was made, and a link if possible.

– FactCheck: have the Trump tax cuts led to lower unemployment and higher wages?

– http://theconversation.com/factcheck-have-the-trump-tax-cuts-led-to-lower-unemployment-and-higher-wages-101460]]>

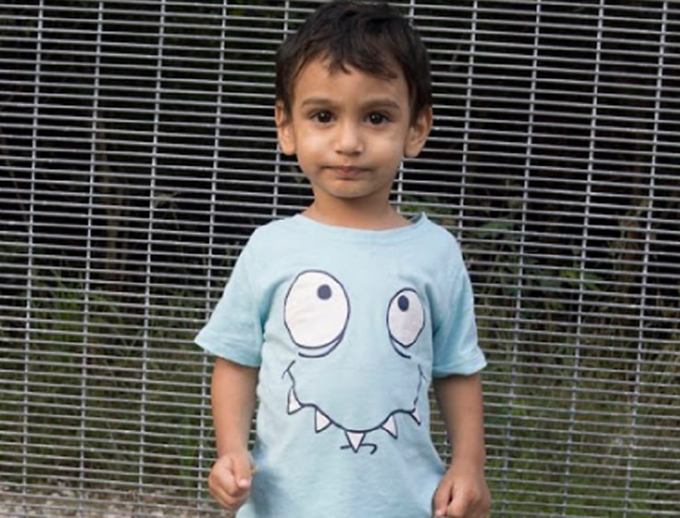

About 90 percent of Nauru is covered in jagged and exposed heaps of petrified coral … unsuitable for both building and agriculture. Image: CWB

About 90 percent of Nauru is covered in jagged and exposed heaps of petrified coral … unsuitable for both building and agriculture. Image: CWB

An out-of-court settlement rehabilitated some of the mined-out areas on Nauru. By 2000 no marketable phosphate remained. Image: CWB

An out-of-court settlement rehabilitated some of the mined-out areas on Nauru. By 2000 no marketable phosphate remained. Image: CWB

With the date for this year’s second Fiji general election since the 2006 coup yet to be announced, one of the questions is will there be a free media for the campaign? Sri Krishnamurthi in Suva talks to some media commentators who are not optimistic.

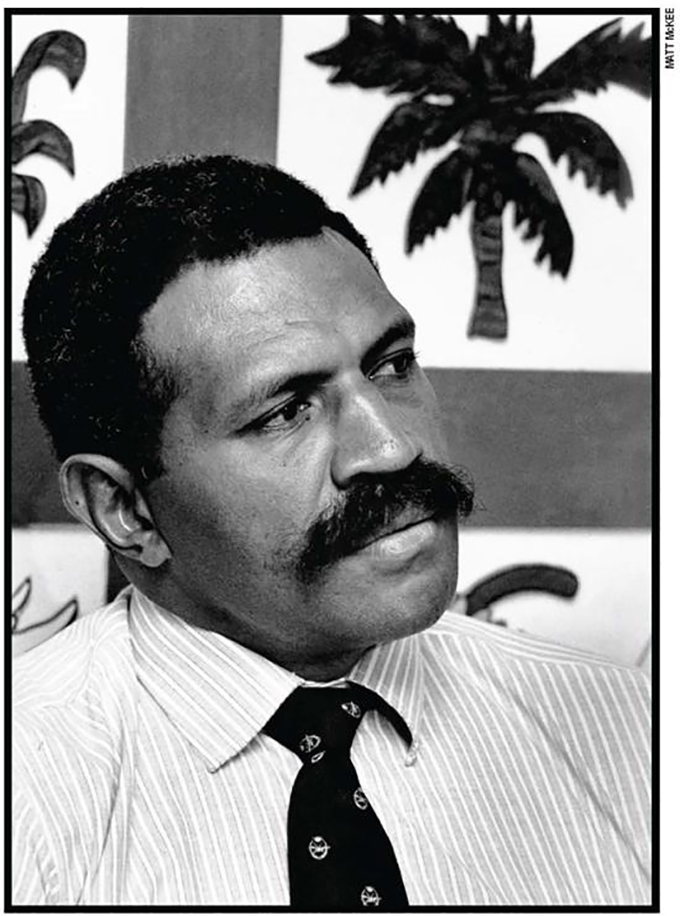

With the date for this year’s second Fiji general election since the 2006 coup yet to be announced, one of the questions is will there be a free media for the campaign? Sri Krishnamurthi in Suva talks to some media commentators who are not optimistic. The 1987 Fiji military coups leader Sitiveni Rabuka as he was back then. Image: Matthew McKee/Pacific Journalism Review

The 1987 Fiji military coups leader Sitiveni Rabuka as he was back then. Image: Matthew McKee/Pacific Journalism Review