By Nic Maclellan in Ponerihouen, New Caledonia

In a show of support for the Kanak independence movement, Maohi leader Oscar Manutahi Temaru has joined the campaign trail in New Caledonia, urging voters to support a Yes vote in the country’s referendum on self-determination next month.

Temaru is a former President of French Polynesia and long-time leader of the Maohi independence movement Tavini Huiraatira no Te Ao Maohi. He was joined in New Caledonia by Moetai Brotherson, an elected member of the local Assembly in Tahiti and one of French Polynesia’s representatives in the French National Assembly in Paris.

In New Caledonia, the Tahitian delegates faced a punishing schedule of speaking engagements around the country in the lead up to the referendum vote on November 4.

READ MORE: Special reports on New Caledonia/Kanaky by Dr Lee Duffield

NEW CALEDONIA OR KANAKY? THE INDEPENDENCE VOTE

NEW CALEDONIA OR KANAKY? THE INDEPENDENCE VOTE

Brotherson was welcomed at a public meeting at the University of New Caledonia in Noumea, and then travelled to the rural towns of Foha (La Foa), Waa Wi Lûû (Houailou) and Pwäräiriwa (Ponerihouen).

Speaking at community meetings in each location, he highlighted the longstanding support of Tavini Huiraatira for the Kanak struggle, and called on people to mobilise for the referendum on self-determination.

At a festival in the east coast town of Ponerihouen, Oscar Temaru said he had travelled to New Caledonia to support the independence movement Front de Liberation National Kanak et Socialiste (FLNKS).

“I am here to support them – to show that the international community is here to watch what will happen in New Caledonia,” he said. “We are sure that the accession of New Caledonia to independence and sovereignty will also mean self-determination for our country Maohi Nui.”

Long history

The Maohi independence leader highlighted the long history that links independence movements across the French-speaking Pacific, from Vanuatu to Kanaky-New Caledonia and Maohi Nui-French Polynesia.

In 1977, there were significant challenges to French colonialism across the region. Under the leadership of Jean-Marie Tjibaou, New Caledonia’s main political party Union Calédonienne adopted a position in favour of independence from France instead of autonomy.

In the Anglo-French condominium of New Hebrides, Father Walter Lini joined other leaders to launch a boycott of the 1977 elections, transforming the New Hebrides National Party into the Vanua’aku Pati and ultimately serving as the first Prime Minister of independent Vanuatu.

In 1977, Oscar Temaru also established the Front de Libération de Polynésie (FLP – Polynesian Liberation Front) in Tahiti. The following year, he travelled to the United Nations in New York for the first time, to call for the right to self-determination and an end to nuclear testing on Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls.

“For more than 40 years, we’ve been fighting together to get our independence back,” Temaru said. “Over all those years, so many things have happened: the former leaders of the FLNKS got killed, they’ve had the Matignon Accords and the Noumea Accord. But on November 4, they have the right to decide to decide their future.”

Oscar Temaru highlighted the importance of international scrutiny of the self-determination process, and welcomed the arrival of a United Nations mission to monitor the vote.

While the French government has supported its involvement in recent years, the UN’s role has been contested over many decades.

Refused authority

From 1947, soon after the United Nations was created, France refused to accept UN authority over decolonisation and the right to self-determination. New Caledonia was only reinscribed on the UN list of non-self-governing territories in December 1986, as members of the Pacific Islands Forum supported the FLNKS to successfully lobby for UN General Assembly resolution 41/41.

It took another 27 years for French Polynesia to be similarly re-inscribed with the UN Special Committee on Decolonisation. In 2013, a UN General Assembly resolution on French Polynesia, sponsored by Solomon Islands, Nauru and Tuvalu, was adopted by the 193-member body without a vote.

Moetai Brotherson told a public meeting in La Foa that the FLNKS had achieved more recognition than the Maohi independence movement.

“You’re a bit ahead of us on the path to independence, so we’re watching what is happening with great attention,” he said. “Oscar Temaru was in New York with Jean-Marie Tjibaou in 1986 when New Caledonia was re-inscribed on the list of non-self-governing territories at the United Nations.

“Our re-inscription, however, only came in 2013. You have advanced along the path. You have made agreements with the French State, you have welcome UN special missions, all of this leading to the decision on November 4. But for us, we’re not there yet.”

He noted fundamental legal differences between the three French Pacific dependencies, which all hold a different constitutional status within the French Republic. The 1998 Noumea Accord is entrenched as a sui generis section within the French Constitution, unlike French Polynesia’s 2004 autonomy statute and the 1961 statute for Wallis and Futuna.

The Noumea Accord creates a clear, legally binding pathway for up to three referendums on self‐determination in New Caledonia. In contrast, French Polynesia has no such path to a referendum.

Constitutional difference

Moetai Brotherson explained: ”There is a difference between the constitutional situation of our two countries. Today, Kanaky-New Caledonia is the only territory of the French Republic to have a specific section in the Constitution.

“You, the Kanak people are the only ‘people’, apart from the French people, recognised in the French Constitution. Apart from that reference, there are no overseas peoples, just ‘populations’.

“You’ve achieved this higher level within the laws of the French Republic,” he said. “For us in Maohi Nui – or French Polynesia as they call it – we only have a population, not a people. This is unacceptable for us.”

For Oscar Temaru, international monitoring of November’s referendum is vital, given France’s ongoing refusal to organise a decolonisation process in his own country.

“Re-inscription in 2013 was very important,” he said. “The resolution that has been adopted by the UN General Assembly was very clear. It reminds the administering power of the right of the Maohi people to self-determination, our right to all our resources of our country and also calls for France to answer to the international community on thirty years of nuclear testing.”

However, Brotherson stressed that the French government refuses to acknowledge any role for the United Nations over self-determination in French Polynesia, failing to meet its obligations as an administering power. Each year, under Article 73e of the UN Charter, colonial powers are required to submit information to the United Nations relating to economic, social and political conditions in their territories.

In recent years, France has formally submitted information about New Caledonia, but refused to submit similar information on French Polynesia.

‘Schizophrenic situation’

Brotherson noted: “We’re in this schizophrenic situation where France has two territories listed at the United Nations. In the case of New Caledonia, France collaborates completely with the United Nations. But in our case, they’re in denial about our re-inscription.

“Every time we’re at the UN Decolonisation Committee, the French representative is in the room when the question of New Caledonia is raised, but as soon as they announce discussion of the question of French Polynesia, he leaves.”

In June 2017, Brotherson defeated Patrick Howell of the governing party Tapura Huiraatira, in the election for French Polynesia’s third constituency in the French National Assembly. Today, as a member of the Republican Democratic Left parliamentary group, Brotherson serves on the French parliament’s Foreign Affairs Commission and overseas delegation.

New Caledonia is currently represented in the French National Assembly by Philippe Gomes and Philippe Dunoyer of the anti-independence Calédonie ensemble party. Brotherson told the FLNKS meeting in Ponerihouen: “When I arrived in Paris, I was saddened to see that there were no Kanak brothers in the National Assembly.

“If in coming times, there are still no Kanak deputies in the Parliament, you will still have a voice there. To ensure that your message will be heard in Paris, you can count on me.”

He pledged support for the Kanak people in the French Parliament in the aftermath of November’s referendum: “I hope that – if there is a Yes vote – the current loyalist deputies in the National Assembly will have the intelligence to serve as dignified representatives of the New Caledonian nation that will be born from this referendum.

“But if that’s not the case, I reiterate my commitment – with the approval of your leaders – to act as a spokesperson for your cause within the French parliament.”

Campaigning for Yes

On October 20, more than 2000 people gathered at the major FLNKS festival in Ponerihouen, which marked the end of referendum campaigning in the Kanak customary region of Ajie-Aro. They were joined by the leaders of three major independence parties – Daniel Goa of Union Calédonienne (UC), Paul Neaoutyine of the Parti de Libération Kanak (Palika) and Victor Tutugoro of Union Progressiste Mélanesienne (UPM).

Temaru and Brotherson joined FLNKS representatives and two Corsican independence activists, Francois Benedetti and Alain Mosconi, for a roundtable on sovereignty and decolonisation.

Just as Scotland is debating independence from the United Kingdom and Catalan nationalists want independence for their region in Spain, there is a strong autonomist movement in Corsica. In a significant breakthrough in December last year, Gilles Simeoni led the nationalist alliance Pè a Corsica to victory in the Corsican Assembly, uniting the autonomist party Femu a Corsica and the pro-independence Corsica Libera.

Three months before travelling to New Caledonia for his first visit last May, French President Emmanuel Macron also visited the French-controlled Mediterranean island. Macron, however, refused the nationalists’ longstanding call to recognise Corsican as an official language.

Congratulating the work of the Academy of Kanak Languages (ALK) and the teaching of local indigenous languages in New Caledonian schools, Corsica Libera’s Alain Mosconi noted: “For decades, the French government has hindered the use of dialects, of patois, regional languages and our language in Corsica.

“They’ve promoted French as the official language. This is a lamentable situation. That’s why we call for our national rights and support the Kanak right to nationhood.”

Tavini Huiraatira’s Moetai Brotherson highlighted the common cause of independence movements across the Pacific.

‘We share many things’

“We share many things – we share the same colonial power and the same colonial history,” he said.

“At a time of resistance to colonial rule in Maohi Nui, the resisters were exiled here to New Caledonia. The high chiefs on Raiatea resisted annexation for many years in the Leeward Islands, but were sent here as exiles.

“At the same time, many of your resisters were exiled to the Marquesas Islands, in our homeland.

“Today, colonisation is symbolised by the concentration of wealth in the hands of a few – always the same few – and by a totally inequitable distribution of that wealth. In both our countries, there is wealth enough, but it’s concentrated in a few hands, That’s the challenge of decolonisation, sovereignty and independence.”

Polynesians from Wallis and Futuna and French Polynesia make up 10 per cent of the population of New Caledonia, so Brotherson called on the Kanak people to mobilise for a Yes vote, but to maintain their welcome for people from other lands.

“The Yes must be an inclusive Yes, not one that excludes people, not a Yes that turns people against each other,” he said. “On November 5, everyone must have their place in Kanaky-New Caledonia. You have a chance that we don’t – to have your say about the future through this referendum. You must seize this moment.”

Nic Maclellan is a journalist and researcher specialising in Pacific island affairs. This article was first published in Islands Business.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz

]]>

The disproportionate percentage of young Papua New Guineans calls for more engaging avenues that will translate into overall development at community levels.

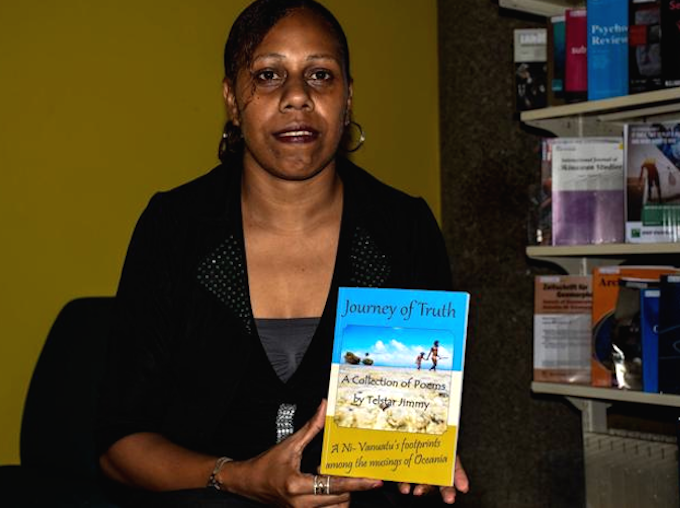

The disproportionate percentage of young Papua New Guineans calls for more engaging avenues that will translate into overall development at community levels. The same way one manoeuvres a soccer ball, the same can be done in life when it comes to health and gender risks. Image: Pauline Mago-King/PMC

The same way one manoeuvres a soccer ball, the same can be done in life when it comes to health and gender risks. Image: Pauline Mago-King/PMC

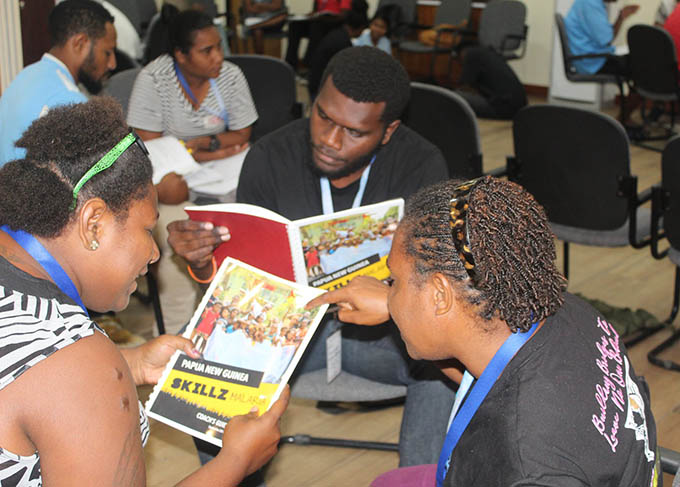

SKILLZ PNG participants during a session. Image: YWCA PNG

SKILLZ PNG participants during a session. Image: YWCA PNG

Professor David Robie presenting a Te Matau a Maui – Mau’s fishhook – to USP journalism coordinator Dr Shailendra Singh for the newsroom to mark the “NZ connection”. Image: Harrison Selmen/Wansolwara

Professor David Robie presenting a Te Matau a Maui – Mau’s fishhook – to USP journalism coordinator Dr Shailendra Singh for the newsroom to mark the “NZ connection”. Image: Harrison Selmen/Wansolwara

Pacific Media Centre director Professor David Robie and MASI president Charles Kadamana with graduating student journalists at the University of the South Pacific. Image: Harrison Selmen/Wansolwara

Pacific Media Centre director Professor David Robie and MASI president Charles Kadamana with graduating student journalists at the University of the South Pacific. Image: Harrison Selmen/Wansolwara