Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Celia McMichael, Senior Lecturer in Geography, University of Melbourne

Climate change is resulting in profound, immediate and worsening health impacts, and no country is immune, a major new report from more than 120 researchers has declared.

This year’s annual report of The Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change, released today, presents the latest data on health impacts from a changing climate.

Among its results, the report found there were 296,000 heat-related premature deaths in people over 65 years in 2018 (a 54% increase in the last two decades), and that global yield potential for major crops declined by 1.8–5.6% between 1981 and 2019.

We are part of the Lancet Countdown sub-working group focusing on human migration in a warming world. We estimate that, based on current population data, 145 million people face potential inundation with global mean sea-level rise of one metre. This jumps to 565 million people with a five metre sea-level rise.

Read more: Coronavirus is a wake-up call: our war with the environment is leading to pandemics

Unless urgent action is taken, the health consequences of climate change will worsen. A globally coordinated effort tackling COVID-19 and climate change in unison is vital, and will mean a triple win: better public health, a more sustainable economy and environmental protection.

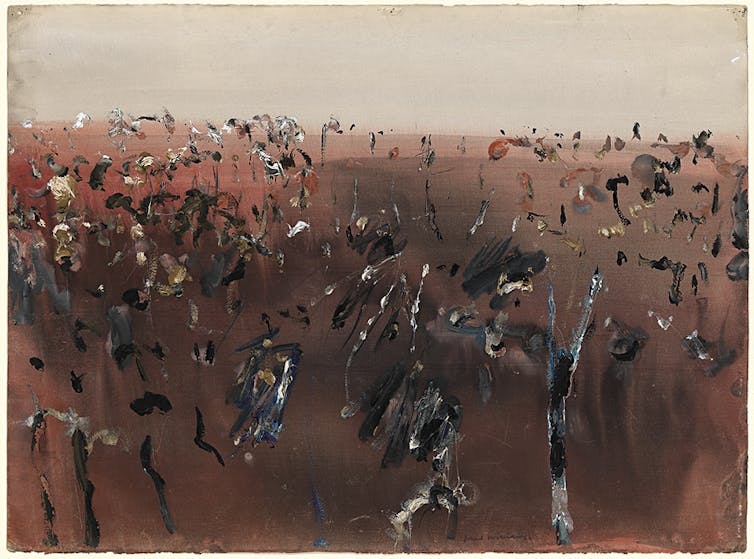

Drought, fires and excessive heat

The 2020 report brings together research from a range of fields, including climate science, geography, economics and public health. It focuses on 43 global indicators, such as altered geographic spread of infectious disease, health benefits of low-carbon diets, net carbon pricing, climate migration and heat-related deaths.

The five hottest years on record have occurred since 2015, and 2020 is on track to be the first or second hottest year on record.

The 2020 Lancet Countdown report found extreme heat continues to rise in every region in the world and particularly affects the elderly, especially those in Japan, northern India, eastern China and central Europe. It is also a big problem for those with pre-existing health conditions and outdoor workers in the agricultural and construction sectors.

Read more: The world endured 2 extra heatwave days per decade since 1950 – but the worst is yet to come

While attributing heat-related deaths to climate change isn’t straightforward, rising temperatures and humidity will mean we can expect heat-related deaths to increase further.

Climate change is also an important contributing factor to drought. The report found that in 2019 excess drought affected over twice the global land surface area, compared with the 1950-2005 baseline.

Drought and health are intertwined. Drought can cause dwindling drinking water supplies, reduced livestock and crop productivity, and an increased risk of bushfire.

Mental health is also at risk, as Australian research from earlier this year confirmed. This looked at the declining mental health of drought-affected farmers in the Murray-Darling Basin over 14 years.

Further, the Lancet Countdown report found that between 2015 and 2019, the number of people exposed to bushfires increased in 128 countries, compared with a 2001-2004 baseline.

Read more: Climate change is bringing a new world of bushfires

Climate change worsens risk factors for more frequent and intense bushfires. We need only look to last summer’s unprecedented bushfires in Australia as a stark illustration. The number of people exposed to the bushfires was amplified by expanding settlements and inadequate risk reduction measures.

Sea level rise, human migration and health

As the world warms and the sea rises, millions of people will be exposed to coastal changes, including inundation and erosion.

Sea-level rise has direct and indirect consequences for human health. In some places, water and soil quality and supply will be compromised due to the intrusion of saltwater. Flooding and wave power will damage infrastructure, including drinking water and sanitation services. And disease vector ecology will also change, such as higher mosquito densities in coastal habitats, potentially causing greater transmission of infectious diseases like dengue or malaria.

However, people and communities may adapt by moving away. In Fiji, for example, at least four communities have relocated in response to coastal changes. The Fijian government notes planned relocation will be a last resort only when other adaptation options are exhausted.

Relocation might also lead to health threats . This includes physical health consequences from altered diets, as fishing and subsistence agriculture may be disrupted. There are also mental health impacts from people losing their attachments and connections to their places of belonging.

But sometimes, migration responses to climate change can have health benefits. Moving from vulnerable coastlines might reduce exposure to environmental hazards such as flooding, be an impetus to seek healthier livelihoods and lifestyles, and improve access to health services.

Our estimation of the number of people facing potential inundation is based on projections of global mean sea-level rise and on current population data.

In a high emissions scenario with warming of 4.5℃, seas could rise by one metre by 2100 relative to 1986–2005. This would see 145 million people face potential inundation.

A collapse of the Western Antarctic Ice Sheet could cause five to six metres of sea level rise. Under this extreme scenario, 565 million people may be inundated.

Read more: How many people will migrate due to rising sea levels? Our best guesses aren’t good enough

It is important to note, however, that uncertainties constrain our ability to forecast migration numbers due to sea-level rise. These uncertainties include future environmental and demographic factors and potential adaptation (and maladaptation) responses, such as living with water or coastal fortification.

So is there any good news?

The 2020 Lancet Countdown report notes improvements in some instances, as some sectors and countries take bold steps to respond to climate change.

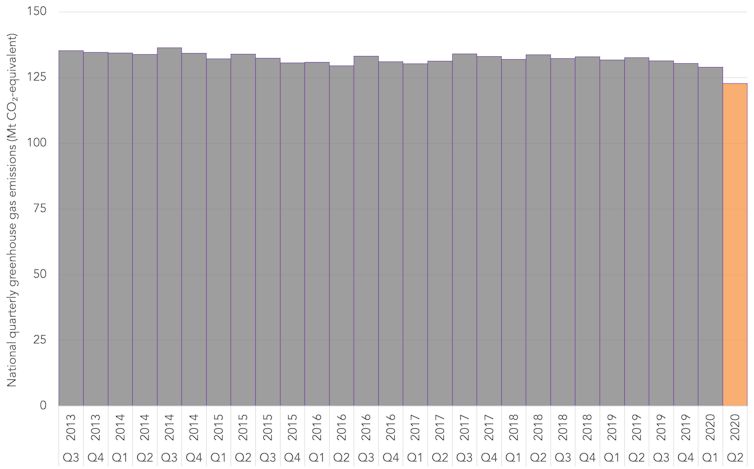

We are seeing, for example, health benefits emerging from the transition to clean energy. Deaths from air pollution attributed to coal-fired power have declined from 440,000 in 2015 to 400,000 in 2018, despite overall population increases.

But more must be done: we need sustained greenhouse gas emission cuts, increased greenhouse gas absorption and proactive adaptation actions. Yet global efforts to address climate change still fall short of the commitments made in the Paris Agreement five years ago.

We cannot afford to focus attention on the COVID-19 pandemic at the expense of climate action.

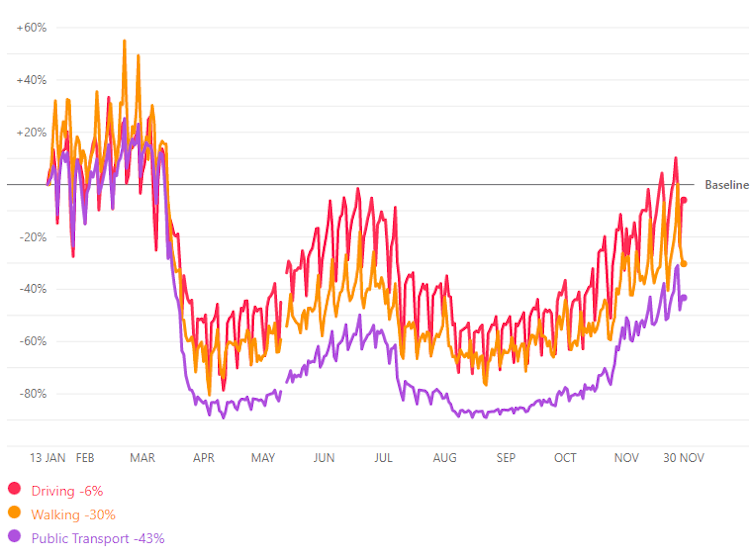

If responses to the economic impacts of COVID-19 align with an effective response to climate change, we’ll see immense benefits for human health, with cleaner air, healthier diets and more liveable cities.

– ref. Climate change is resulting in profound, immediate and worsening health impacts, over 120 researchers say – https://theconversation.com/climate-change-is-resulting-in-profound-immediate-and-worsening-health-impacts-over-120-researchers-say-151027