Headline: Indigenous socialism, with a Chilean face. – 36th Parallel Assessments

Five days before Christmas and 51 years after Salvador Allende was elected as the first socialist president in Chilean history, Gabriel Boric re-made history as the youngest candidate (35) to win that office. A former student activist and Congressman from Punta Arenas in Tierra del Fuego, he first rose to prominence during the 2011 student demonstrations against increases in tuition fees at the University of Chile, then again during the 2019 anti-austerity demonstrations precipitated by a 30 percent rise in public transportation prices in Santiago. In 2021 Boric rode a wave of votes (the most since mandatory voting laws were dropped in 2012) to win 56 percent of the national ballot (although less than 60 percent of eligible voters cast ballots, leaving a large pool of disaffected or apathetic voters in the political mix). He campaigned on an overtly socialist, specifically anti-neoliberal agenda, promising to tax the super rich, expand social services and environmental conservation programs, promote pension reform and universal health care and make the fight against income inequality his main priority in a country with the worst income gaps in South America.

Boric’s victory is remarkable given the tone of the campaign. His opponent, Jose Antonio Kast, embraced Trumpian-style rhetoric and openly said that he would be the “Bolsonaro of Chile” (Jair Bolsonaro is the national-populist president of Brazil who emulates Trump, now hospitalized because of complications from a knife attack in 2018). He railed against Boric as someone who would turn Chile into Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua, or even Peronist Argentina. Kast is the son of a card-carrying Nazi who fled to Chile after WW2 and built a sausage-making business that served as a launching pad for his children’s economic and political ambitions during the Pinochet dictatorship (the Kast family dynasty is prominent in Chilean rightwing circles). Jose Antonio Kast openly praised the strongman and his neoliberal economic policies during his presidential campaign while downplaying the thousands of murdered, tortured and exiled victims of Pinochet’s regime. He won a plurality of votes in the presidential primaries but lost decisively in the second round run-off between the two largest vote-getters.

Surprisingly given their vitriol during the campaign, both Kast and the outgoing president, rightwing Sebastian Pinera (son of a Pinochet Labour Minister) extended their congratulations and offers of support to the newly elected Boric, who will be inaugurated in March. This makes the transition period especially important, as it may offer a window of opportunity for Boric to negotiate inter-partisan consensus on key policy issues.

Boric’s election follows that of several other Leftist presidential candidates in Latin America in the last two years, including those in Bolivia (a successor to the illegally ousted Evo Morales), Peru (an indigenous school teacher and teacher’s union leader) and Honduras (the wife of a former president ousted by a coup tacitly backed by the Obama administration). Centre-Left presidents govern in Belize, Costa Rica, Guyana, Mexico, Panama, and Suriname. A former leftwing mayor of Bogota is the front runner in this year’s Colombian presidential elections (now in Right-center hands) and former president Lula da Silva is leading the polls against Bolsonaro for the October canvass in Brazil. These freely elected Leftists are bookended on one end by authoritarian counterparts in Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela and on the other by right-leaning elected governments in Brazil, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala Paraguay and Uruguay. Argentina, which has a Peronist government, straddles the divide between Left and Right owing to the odd (and very kleptocratic) populist coalition that makes up the governing Party.

One might say that the region is relatively balanced ideologically speaking, but with an emerging tilt to the moderate Left as a result of the exposure by the pandemic of inherent flaws in the market driven economic model that dominated the region over the last thirty years. It remains to be seen if this political tilt will eventuate in the type of socio-economic reforms upon which the successful Leftists candidates campaigned on. What is pretty clear is that it will not be a repeat of the so-called “Pink Tide” that swept the likes of Hugo Chavez and Evo Morales into power in the early 2000s, both in terms of the extent of their policy ambitions and the style in which they rule. This most recent wave still retains many characteristics of the much lauded (by the Left) indigenous socialism of twenty years ago, but it is now tempered by the policy failures and electoral defeats that followed its heyday. It is indigenous not only because of its origins in populations that descended from pre-colonial civilizations (although there is still plenty of indigena in Latin American socialism), but because it originates in domestic and regional ideological thought and practice. Within this dual sense of the phrase, it is moderation and pragmatism that appears to differentiate the original 2000s versions from what is emerging today.

Western observers believe that the regional move Left may give China an opportunity to make strategic inroads in the hemisphere. That view betrays ignorance of the Latin American Left, which is not driven by any Communist orthodoxy or geopolitical alignment with China (or even blind hatred of the US), but instead is a very heterogenous mix of indigenous, environmental, trade union, student and social movement activism that among other things is progressive on gender and sexuality rights and climate change. This is not a Leninist/Maoist Left operating on vanguardist principles of “democratic centralism,” but instead a fluid amalgam of modern (industrial) and post-modern (post-industrial) causes. What that means is, since China is soon to overtake the US as the primary extractor of raw materials and primary goods from Latin America and has a checkered environmental record as part of its presence as well as a record of authoritarian management practices in Chinese controlled firms, it is by no means certain that it will be able to leverage emergent elected Latin American Left governments in its favor.

In fact, given what has been seen in its relationship with the three authoritarian leftist states, many of the elected Leftist governments may prove reticent to deepen ties with the Asia giant precisely because of concerns about a loss of economic independence (fearing debt diplomacy, among other things). The Belt and Road initiative may seem an attractive proposition at first glance, but it can also serve to choke national sovereignty on the economic as well as diplomatic fronts. Boric and his supporters are very much aware of this given problems that have risen from Chinese investment in the Chilean mining and forestry sectors (such as disputes over water and indigenous land rights).

As for the internal political dynamics at play in Chile. For Boric to succeed he will have to deliver on very high public expectations. For that to happen he needs to navigate a three-cornered political obstacle course.

In one corner is his own political support base, which is comprised of numerous factions with different priorities, albeit all on the “Left” side of the policy agenda. This include members of the Constitutional Convention charged with drawing up a replacement for the Pinochet-era constitution still in force (something that was agreed to by the outgoing government in the wake of the 2019 protests). The Convention must design a new constitution with procedural as well as substantive features. That is, it must demarcate governance processes as well as grant enshrined rights. The balance between the two is tricky, because a minimalist approach that focuses on processes and procedures (such as elections, office terms and separation of powers) does not address what constitutes a “right” in a democracy and who should have rights bestowed upon them, whereas an encompassing approach that attempts to cover the universe of social endeavour risks granting so many rights to so many people and agencies that it overwhelms regulatory processes and becomes meaningless is real terms (the latter happened with the 1988 Brazilian constitutional reform, which covers a plethora of topics that have been cumbersome to enforce or implement in practice).

Not all of the delegates share the gradualist, incremental, moderately pragmatic approach to policy agenda-setting that Boric espouses, and because they are independently elected, it signals that the future of Chile resides in a very much redesigned approach to governance. It is even possible that delegates consider moving from a presidential to a parliamentary democracy given that Chile already has a very splintered party system that requires building multiparty coalitions to form majorities in any event. Whatever is put on the table, Boric will have to urge delegates to exercise caution when it comes to sensitive issues like taxation, military funding and autonomy, land reform (including indigenous land rights, which have been the source of violent clashes in recent years) etc., less it provoke a destabilizing backlash from conservative sectors. In light of that and the strength of his election victory, it will be interesting to see how Boric approaches the Constitutional Convention, how his Cabinet shapes up in terms of personnel and policy orientation, and how his support bloc in Congress responds to his early initiatives.

The latter matters because Boric inherits a deeply fragmented Congress that has a slim Opposition majority but which in fact has seen all centrist parties lose ground to more extreme parties on both the Right and Left. Even so and depending on the issue, cross-cutting alliances within Congress currently transcend the usual Left-Right divide, so it is possible that he will be able to use his incrementalist moderate approach to advance a Left-nationalist project that keeps most parties aligned or at least does not step on too many Party toes. On the other hand, the fact Boric won 56 percent of a vote in which only 56 percent of eligible voters went to the polls means that his policy proposals could easily be rejected on partisan grounds given the lack of unified majorities on either side of the ideological divide.

In another corner are the political Opposition, dominated by Pinochetista legacies but increasingly interspersed with neo-MAGA and alt-Right perspectives (what I shall call Chilean nationalist conservatism). The Right has a significant presence in the Constitutional Convention so may be able to act as a brake on radical reforms and in doing so create space for Boric and his supporters in the convention to push more moderate alterations to the magna carta (each constitutional change requires a 2/3 vote in order to pass. This will force compromise and moderation by the drafters if anything is to be achieved).

The fact that Pinera and Kast, scions of the Pinochetista wing (they do not like that name and disavow ties to the dictatorship other than support for its “Chicago School” economic policies), readily conceded and offered support to Boric may indicate that the neoliberal wing of Chilean conservatism understands that many rightwing voters may have abstained from voting or voted for Boric on economic nationalist grounds as a result of Pinera’s adherence to market-oriented policies that clearly were not alleviating poverty or providing effective pandemic relief even as the upper ten percent of society continued to capture an increasing percentage of national wealth. This could mean that the Chilean Right is less disloyal to the democratic process as it was in the run up to Allende’s election and therefore more committed—or at least some of it is—to trying to reach compromises with Boric on pressing policy issues. In that sense their presence in the Constitutional Convention may prove to be a moderating influence.

Conversely, in the wake of the defeat the Chilean Right might fragment between Pinochetista and newer factions, which will mean that conciliation with government initiatives will be difficult until the internal power struggle within the Right is resolved, and then only if it is resolved in a way that marginalizes Trump and Bolsonaro-inspired extremists within conservative ranks. After all, what sells in the US or Brazil does not necessarily sell in Chile. The most important arena in which this internal dispute will have to be resolved is Congress, where extreme Right parties have taken seats from traditional conservative vehicles. On the face of it that spells trouble for Boric, but the narrow Right majority in Congress and Pinochetista disdain for their extreme counterparts may grant him some room for manoeuvre.

In a very real sense, Boric’s political fate will be determined in the first instance by the coalition politics within his own support base as well as within the Right Opposition.

The final obstacle is getting the Chilean military on-board with the new government’s project. Of the three factors in this political triumvirate, the armed forces are both a constant and a wild card. They are a constant in that their deeply conservative disposition and institutional legacies are unshakable and guaranteed. This means that Boric’s government must tread delicately when it comes to civil-military affairs, both in terms of national security policy-making but also with regard to the prerogatives awarded the armed forces under the Pinochet constitution. Along with the Catholic Church and landed agricultural interests, the Chilean armed forces are one of the three pillars of traditional Chilean conservatism. This ideological outlook extends to the national paramilitary police, the Carabineros, who are charged with domestic security and repression (the two overlap but are not the same).

Democratic reforms (such as allowing female combat pilots) have been introduced into the military, especially during the tenure of former president Michelle Bachelet as Defense Minister, but the overall tone of civil-military relations over the years since democracy was restored (1990) has been aloof, when not tense. Revelations that Pinochet and other senior offices had received kickbacks from weapons dealers produced a paratrooper mutiny in 1993, and when Pinochet returned from voluntary exile in the UK in 2000 he was greeted with full military honors in a nationally televised airport ceremony. This rekindled old animosities between Right and Left that saw the military high command issue veiled warnings about leaving sleeping dogs lie. Until now, that warning has been heeded.

The role of the military as political guarantor and veto agent is enshrined in the Pinochet constitution. So is its receipt of a percentage of pre-tax copper exports. These powers and privileges have been pared down but not eliminated entirely over the years and will be a major focus of attention of the Constitutional Convention. With 7,800 kilometers of land bordering on three states that it has had wars with and 6,435 kilometers of ocean frontage extending out to Easter Island (and all the waters within that strategic triangle), the Chilean military is Army-dominant even if the other two service branches are robust given GDP and population size (in fact, the Chilean military is one of the most modernized in Latin America thanks to its direct access to copper revenues). What this means is that the Chilean armed forces exhibit a state of readiness and geopolitical mindset that is distinct from that of most of its neighbors and which gives it unusual domestic political influence.

The Chilean armed forces High Command continues to operate according to Prussian-style organizational principles that, if instilling professionalism and discipline within the ranks, also leads to highly concentrated and centralized decision-making authority in the services Flag-rank leadership. Moreover, although the Prussian legacy has diluted in recent years (with the Army retaining significant Prussian vestiges, to include parade march goose-stepping, while the Air Force and Navy have adored UK and US organizational models), the Chilean Navy is widely seen as a bastion for the most conservative elements in uniform, with the Air Force encompassing the more “liberal” wing of the officer corps and the Army and Carabineros leaning towards the Navy’s ideological position. The effect is to make democratic civil-military relations largely hinge on the geopolitical perspectives and attitudes of service branch leaders towards the elected government of the day.

Successfully navigating these three obstacle points will be the key to Boric’s success. The groundwork for that is being laid now, in the period between his election and inauguration. Should he be able to reach agreement with supporters and opposition on matters like the scope of constitutional reform and short-term versus medium-term fiscal and other policy priorities in the midst of a public health crisis, then his chances of leaving a legacy of positive change are high. Should he not be able to do so, then his attempt to impart a dose of pragmatism and moderation on Chilean indigenous socialism could well end in disarray.

We can only hope that for Boric and for Chile, the country advances por la razon y no por la fuerza.

Analysis syndicated by 36th Parallel Assessments –

![]()

Otago University covid-19 experts copping abuse from anti-vaxxers

By Hamish MacLean in Dunedin

University of Otago covid-19 experts are not immune to the increasingly vitriolic attacks dished out to scientists commenting on New Zealand’s pandemic response.

Among a litany of attacks University of Otago epidemiologist Professor Michael Baker has endured over the course of the pandemic, at the start of this week a caller told him he had “a target on his back”.

Professor Baker said he kept the caller on the line for about 20 minutes and asked him what that meant “in real terms”.

The caller was an anti-vaxxer who was accusing Professor Baker of propaganda on behalf of pharmaceutical companies, telling him vaccines were dangerous, especially so for children.

The caller had half-baked information gleaned from various sources that did not really make sense, Professor Baker said.

“He had these slogans he was throwing at me, but when I asked him what he meant he didn’t really have any answers.”

This week it was revealed University of Auckland professors Shaun Hendy and Siouxsie Wiles have argued to the Employment Relations Authority their employer was not doing enough to protect them as they shared their expertise with the public.

Professor would call police

But Professor Baker said he had not raised any concerns for his safety with his employer, the University of Otago.

If anyone made a threat where he felt he or his family was unsafe he would not hesitate to involve the police.

The Wellington-based scientist received the occasional phone call where a caller delivered a stream of abuse and hung up, but Professor Baker said he was most likely to receive abuse in the form of emails, averaging a few attacks by email every day.

As an exercise, Professor Baker began classifying the forms of abuse he received into “five categories of insult”, he said.

There were the incoherent streams of abuse, which were easily dealt with, he said.

Some people had major grievances but did not know where to go, and contacted him to vent and, in some extremely sad cases, he would reply and express sorrow and sympathy.

There were anti-vax propagandists whose positions were not based on facts, which he ignored.

There were those with ideological stances who disapproved of the government’s overall strategy, who at times delved into conspiracy theories.

Personal attacks stream

Finally, the group he found the hardest to deal with came as personal attacks from a small stream of people who persistently contacted him, and tried to undermine his ability to comment.

“Talking about how you look, or how you appear – they’re obviously making quite a concerted effort to look at where you might feel a bit vulnerable,” he said.

The attacks had never made him question his role of speaking publicly about the pandemic response, Professor Baker said.

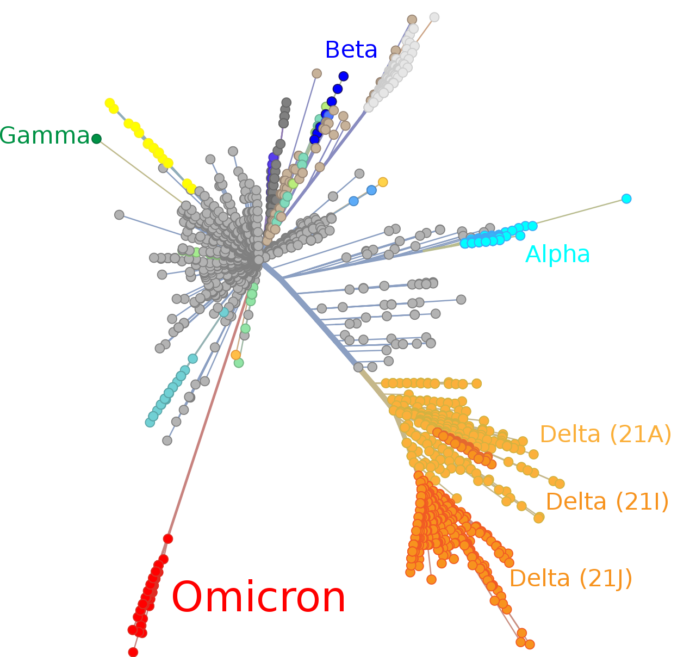

University of Otago evolutionary virologist Dr Jemma Geoghegan said she, too, had not raised any concerns with her employer.

She said “no” to about 90 percent of media requests because the issues were not related to her field of expertise.

In limiting her media exposure, she had limited the number of people who wanted to harass her about her expertise, Dr Geoghegan said.

“I don’t generally speak about vaccines, so [that] abuse isn’t aimed at me,” the Dunedin scientist said.

‘Weirdly strong views’

However, she had published on covid-19 origins and people had “weirdly strong views about that”.

The issues dealt with by her Auckland counterparts were not surprising though and she had sympathy for them.

“This is happening all around the world,” Dr Geoghegan said.

“I’ve got international collaborators that … I think their mental health has suffered.

“Before covid, or at the start of covid, they were really prominent on Twitter and stuff like that, and now they’ve had to delete their accounts because of the amount of abuse they’ve got.”

Hamish MacLean is an Otago Daily Times journalist. This article is republished under a community partnership agreement with RNZ and this story first appeared in the Otago Daily Times

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz