POLITICAL BYTES: By Ian Powell

There is a reported apparent rift within cabinet between Foreign Minister Nanaia Mahuta and Defence Minister Andrew Little over Aotearoa New Zealand’s position in the widening conflict between the United States and China.

While at its core it is over relative economic power, the conflict is manifested by China’s increased presence in the Pacific Ocean, including military, and over Taiwan. Both countries have long Pacific coastlines.

However, the United States has a far greater and longstanding economic and military presence (including nuclear weapons in South Korea) in the Pacific.

Despite this disparity, the focus is on China as being the threat. Minister Mahuta supports continuing the longstanding more independent position of successive Labour and National-led governments.

This goes back to the adoption of the nuclear-free policy and consequential ending of New Zealand’s military alliance with the United States in the mid-1980s.

On the other hand, Minister Little’s public utterances veer towards a gradual shift away from this independent position and towards a stronger military alignment with the United States.

This is not a conflict between socialist and capitalist countries. For various reasons I struggle with the suggestion that China is a socialist nation in spite of the fact that it (and others) say it is and that it is governed by a party calling itself communist. But that is a debate for another occasion.

Core and peripheral countries

This conflict is often seen as between the two strongest global economic powers. However, it is not as simple as that.

Whereas the United States is an imperialist country, China is not. I have discussed this previously in Political Bytes (31 January 2022): Behind the ‘war’ against China.

In coming to this conclusion I drew upon work by Minqi Li, professor of economics at the University of Utah, who focussed on whether China is an imperialist country or not.

He is not soft on China, acknowledging that it ” . . . has developed an exploitative relationship with South Asia, Africa, and other raw material exporters”.

But his concern is to make an objective assessment of China’s global economic power. He does this by distinguishing between core, semi-periphery, and periphery countries:

“The ‘core countries’ specialise in quasi-monopolistic, high-profit production processes. This leaves ‘peripheral countries’ to specialise in highly competitive, low-profit production processes.”

This results in an “…unequal exchange and concentration of world wealth in the core.”

Minqi Li describes China’s economy as:

“. . . the world’s largest when measured by purchasing power parity. Its rapid expansion is reshapes the global geopolitical map leading western mainstream media to begin defining China as a new imperialist power.”

Consequently he concludes that China is placed as a semi-peripheral county which predominately takes “. . . surplus value from developed economies and giving it to developing economies.”

In my January 2022 blog, I concluded that:

“Where does this leave the ‘core countries’, predominately in North America and Europe? They don’t want to wind back capitalism in China. They want to constrain it to ensure that while it continues to be an attractive market for them, China does not destablise them by progressing to a ‘core country’.”

Why the widening conflict now?

Nevertheless, while neither socialist nor imperialist, China does see the state playing a much greater role in the country’s economy, including increasing its international influence. This may well explain at least some of its success.

So why the widening conflict now? Why did it not occur between the late 1970s, when China opened up to market forces, and in the 1990s and 2000s as its world economic power increased? Marxist economist and blogger Michael Roberts has provided an interesting insight: The ‘New Washington Consensus’.

Roberts describes what became known as the “Washington Consensus” in the 1990s. It was a set of economic policy prescriptions considered to constitute the “standard” reform package promoted for economically struggling developing countries.

The name is because these prescriptions were developed by Washington DC-based institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, World Bank and the United States Treasury.

The prescriptions were based on so-called free market policies such as trade and finance liberalisation and privatisation of state assets. They also entailed fiscal and monetary policies intended to minimise fiscal deficits and public spending.

But now, with the rise of China as a rival economic global power globally and the failure of the neoliberal economic model to deliver economic growth and reduce inequality among nations and within nations, the world has changed.

What World Bank data reveals

Roberts draws upon World Bank data to highlight the striking nature of this global change. He uses a “Shares in World Economy” table based on percentages of gross domestic production from 1980 to 2020.

Whereas the United States was largely unchanged (25.2 percent to 24.7 percent), over the same 40 years, China leapt from 1.7 percent to 17.3 percent. China’s growth is extraordinary. But the data also provides further insights.

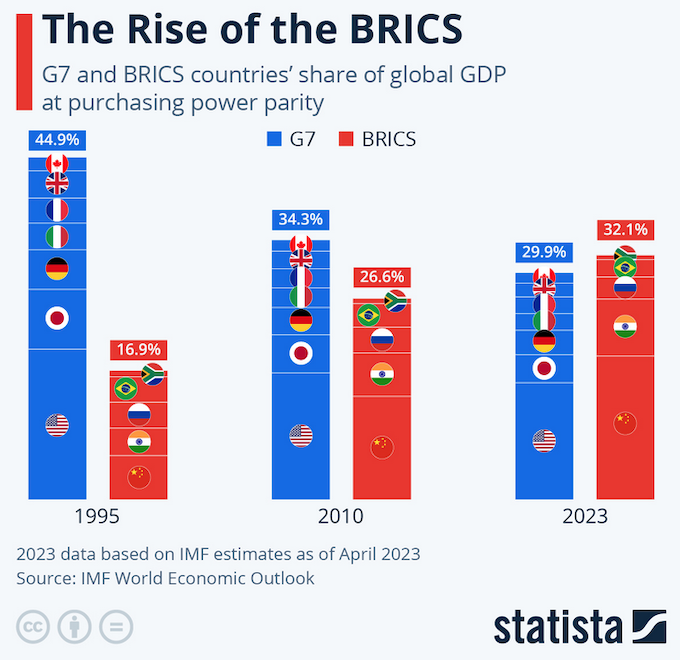

Economic blocs are also compared. The G7 countries declined from 62.5 percent to 47.2 percent while the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) also fell — from 78 percent to 61.7 percent.

Interestingly while experiencing a minor decline, the United States increased its share within these two blocs — from 40.3 percent to 52.3 percent in G7 and from 32.3 percent to 40 percent in OECD. This suggests that while both the G7 and OECD have seen their economic power decline, the power of the United States has increased within the blocs.

Roberts use of this data also makes another pertinent observation. Rather than a bloc there is a grouping of “developing nations” which includes China. Over the 40 year period its percentage increased from 21.5 percent to 36.4 percent.

But when China is excluded from the data there is a small decline from 19.9 percent to 19.1 percent. In other words, the sizeable percentage of growth of developing countries is solely due to China, the other developing countries have had a small fall.

In this context Roberts describes a “New Washington Consensus” aimed at sustaining the “. . . hegemony of US capital and its junior allies with a new approach”.

In his words:

“But what is this new consensus? Free trade and capital flows and no government intervention is to be replaced with an ‘industrial strategy’ where governments intervene to subsidise and tax capitalist companies so that national objectives are met.

“There will be more trade and capital controls, more public investment and more taxation of the rich. Underneath these themes is that, in 2020s and beyond, it will be every nation for itself — no global pacts, but regional and bilateral agreements; no free movement, but nationally controlled capital and labour.

“And around that, new military alliances to impose this new consensus.”

Understanding BRICS

This is the context that makes the widening hostility of the United States towards China highly relevant. There is now an emerging potential counterweight of “developing countries” to the United States’ overlapping hegemons of G7 and the OECD.

This is BRICS. Each letter is from the first in the names of its current (and founding) members — Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. Around 40 countries have expressed interest in joining this new trade bloc.

These countries broadly correspond with the semi-periphery countries of Minqi Li and the developing countries of Roberts. Predominantly they are from Africa, Asia, Middle East, and Central and South America.

Geoffrey Miller of the Democracy Project has recently published (August 21) an interesting column discussing whether New Zealand should develop a relationship with BRICS: Should New Zealand build bridges with BRICS?

Journalist Julian Borger, writing for The Guardian (August 22), highlights the significant commonalities and differences of the BRICS nations at its recent trade summit: Critical BRICS trade summit in South Africa.

Al Jazeera (August 24)has updated the trade summit with the decision to invite Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates to join BRICS next January: The significance of BRICS adding six new members .

Which way New Zealand?

This is the context in which the apparent rift between Foreign Minister Nanaia Mahuta and Defence Minister Andrew Little should be seen.

It is to be hoped that that whatever government comes into office after October’s election, it does not allow the widening conflict between the United States and China to water down Aotearoa’s independent position.

The dynamics of the G7/OECD and BRICS relationship are ongoing and uncertainty characterises how they might play out. It may mean a gradual changing of domination or equalisation of economic power.

After all, the longstanding British Empire was replaced by a different kind of United States empire. It is also possible that the existing United States hegemony continues albeit weakened.

Regardless, it is important politically and economically for New Zealand to have trading relations with both G7 and developing countries (including the expanding BRICS).

Ian Powell is a progressive health, labour market and political “no-frills” forensic commentator in New Zealand. A former senior doctors union leader for more than 30 years, he blogs at Second Opinion and Political Bytes, where this article was first published. Republished with the author’s permission.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz