Analysis by Geoffrey Miller

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) has New Zealand firmly in its sights.

Last week, New Zealand’s foreign minister Nanaia Mahuta attended the annual NATO foreign ministers’ meeting in Brussels – alongside her counterparts from Australia, Japan and South Korea.

Mahuta’s participation came after New Zealand’s then Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern joined last June’s NATO leaders’ summit in Madrid. Mahuta was also a guest at the NATO foreign ministers’ meeting in April 2022, albeit only in virtual form.

At a more granular level, a NATO military delegation visited New Zealand last month for meetings with officials in Wellington. The head of the delegation said NATO was ‘determined’ to ‘deepen and strengthen our cooperation with our Indo-Pacific partners’.

And this week, top NATO official Benedetta Berti is visiting Wellington. As part of her visit, Berti – who heads NATO’s Policy Planning Unit in the Secretary General’s office – will speak to the New Zealand Institute of International Affairs (NZIIA) on the impact of the war in Ukraine on the Indo-Pacific. Berti will also explain why NATO is seeking to expand its ties with countries in the region such as New Zealand, according to advance NZIIA publicity material for the event.

The grouping of four Indo-Pacific countries is sometimes referred to as the AP4, or ‘Asia Pacific Four’, particularly by the more hawkish Australia and Japan.

So far, New Zealand has tended to avoid using the AP4 acronym, perhaps to play down the implication that Wellington has joined yet another new bloc.

The website of New Zealand’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (MFAT) contains only a single mention of the AP4 – after Mahuta’s attendance at the NATO foreign ministers’ meeting last year. There is no mention of AP4 at all on the Ministry of Defence or Beehive ministerial websites, according to a Google search.

NATO itself has also generally shied away from using the AP4 acronym, perhaps in deference to New Zealand’s sensibilities. But this might be starting to change. Jens Stoltenberg, the NATO Secretary General, talked openly about the potential of the AP4 at a speech at Tokyo’s Keio University in February.

In that address, Stoltenberg told his audience that NATO had ‘in many ways…already institutionalised’ the AP4 and described the four countries’ participation at the NATO leaders’ summit in Spain in 2022 as a ‘historic moment’.

We can expect to hear much more about the AP4 in the future.

Stoltenberg has publicly invited all four AP4 leaders to attend this year’s leaders’ summit in the Lithuanian capital of Vilnius.

In diplomatic terms, this probably means New Zealand Prime Minister Chris Hipkins and the other three AP4 leaders have already decided to go.

This is significant.

For one thing, it means Jacinda Ardern’s presence at last year’s NATO summit in Madrid was not just a one-off move to show solidarity with NATO countries in the immediate aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Second, it shows how New Zealand is continuing to forge a more hardline foreign policy stance under Hipkins’ leadership.

After all, the involvement of the AP4 in NATO is being driven chiefly by the alliance’s interest in China.

At the Madrid summit last year, NATO launched its new long-term Strategic Concept that openly called out China for its ‘stated ambitions and coercive policies’ and pinpointed Beijing as a source of ‘systemic challenges’ for the alliance.

And much of the press conference after last week’s NATO foreign ministers’ meeting that New Zealand’s Nanaia Mahuta also attended was focused squarely on China.

Stoltenberg told media that China was ‘coming closer to us’ and cited a range of familiar Western criticisms of Beijing – ranging from its ‘assertive behaviour’ in the South China Sea, to actions over Hong Kong, Taiwan and its ties with Moscow – that made it necessary for NATO to ‘update and develop’ its stance towards China.

Indeed, the NATO Secretary General openly linked the alliance’s recent deepening of partnerships with Indo-Pacific countries such as New Zealand with NATO’s China strategy – which he called a ‘huge effort’.

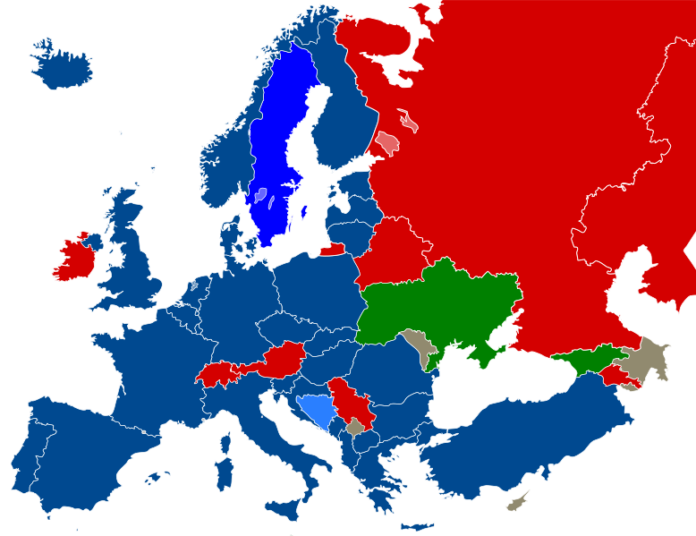

Of course, unlike Finland – which became NATO’s 31st member last week – New Zealand cannot formally join NATO, given the alliance’s geographic focus.

But if New Zealand continues to align itself with NATO as part of the AP4 – which could be seen as ‘NATO plus’ – the implications could be as significant as the extraordinary signals from defence minister Andrew Little that Wellington could soon join non-nuclear components of the AUKUS pact between Australia, the United Kingdom and United States.

For one, it means that New Zealand will almost certainly strive to meet NATO’s military spending target of 2 per cent of GDP – a figure which Stoltenberg described last week as a ‘floor not a ceiling’.

To that end, New Zealand’s defence minister Andrew Little is continuing a softening-up campaign in the media to pave the way for greater military spending, ahead of the imminent reporting-back of a defence policy review committee and the Government’s Budget in May.

Any response from Beijing to the latest developments on New Zealand’s involvement with NATO and AUKUS has yet to be fully felt.

But China – New Zealand’s biggest trading partner – made no secret of its displeasure after Jacinda Ardern attended the NATO summit in Spain last year. At the time, the Chinese Embassy in Wellington issued a statement noting Beijing’s opposition to ‘all kinds of military alliances, bloc politics, or exclusive small groups’, while a Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson said NATO should not seek to ‘replicate the kind of bloc confrontation seen in Europe here in the Asia-Pacific’.

After the NATO meeting in Madrid in June 2022, Jacinda Ardern gradually reined in New Zealand’s more hawkish positioning with more soothing tones towards Beijing – culminating in her meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the APEC summit in Thailand in November and her pledge to travel to China early in 2023.

Upon taking over the Prime Ministerial role from Ardern in January, Hipkins said a trip to China would be high on his priority list – but the signals have been rather mixed since then. Last month, Hipkins appeared to play down expectations of a visit to Beijing, citing ‘moving parts’ and domestic pressures during New Zealand’s election year.

Delaying an invitation to New Zealand’s Prime Minister to visit China would certainly be one way for Beijing to signal frustration.

Chris Hipkins may well be heading to the NATO summit in Vilnius.

But it could mean he has to wait longer to visit Beijing.

Geoffrey Miller is the Democracy Project’s geopolitical analyst and writes on current New Zealand foreign policy and related geopolitical issues. He has lived in Germany and the Middle East and is a learner of Arabic and Russian. He is currently working on a PhD on New Zealand’s relations with the Gulf states.