The new media development policy being proposed by the Papua New Guinea Communications Minister, Timothy Masiu, could lead to more government control over the country’s relatively free media.

The new policy suggests a series of changes including legislative amendments. But media and stakeholders are not being given enough time to examine the details and study the long-term implications of the policy.

The initial deadline for feedback has been extended by another seven days from today. However, the Media Council of PNG (MCPNG) has requested a consultation forum with the government, as it seeks wider input from research organisations, academia and regional partners.

The government’s intention to impose greater control over aspects of the media, including the MCPNG, is ringing alarm bells through the region. This is to be done by re-establishing the council through the enactment of legislation.

The policy envisages the council as a regulatory agency with licensing authority over journalists.

The MCPNG was established in 1989 as a non-profit organisation representing the interests of media organisations. Apart from a brief period in the earlier part of its existence, it has largely been unfunded.

Over three decades, its role has shifted to being a representative body for media professionals and a voice for media freedom.

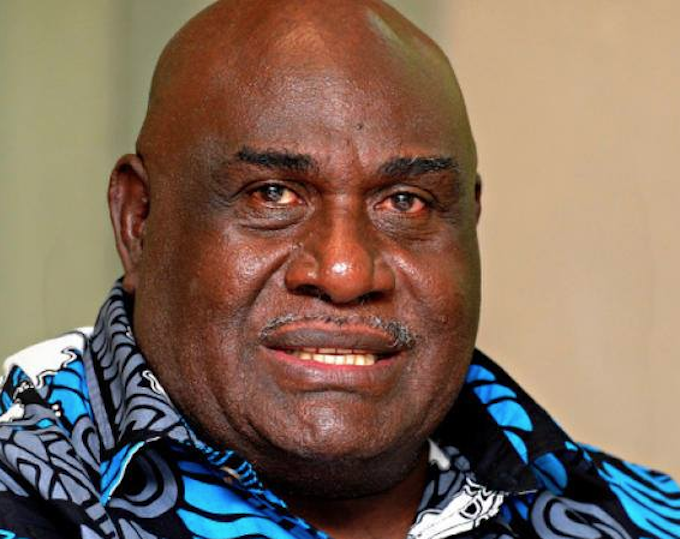

The president of the council, Neville Choi, says there are aspects of the media that need government support. These include protection and training of journalists. However, the media is best left as a self-regulating industry.

According to Choi:

“Media self-regulation is when media professionals set up voluntary editorial guidelines and abide by them in a learning process open to the public. By doing this, independent media accept their share of responsibility for the quality of public discourse in the country, while preserving their editorial autonomy in shaping it. The MCPNG was set up with this sole intent.

“It is not censorship, and not even self-censorship. It is about establishing minimum principles on ethics, accuracy, personal rights while preserving editorial freedom on what to report, and what opinions to express.

The regulatory framework proposed for the new media council includes licensing for journalists. Licensing is one of the biggest red flags that screams of government control.

While the PNG media has been resilient in the face of many challenges, journalists who have chosen to cover issues of national importance have been targeted with pressure coming directly from within government circles.

In 2004, the National Broadcasting Corporation’s head of news and current affairs, Joseph Ealedona, was suspended for a series of stories on the military and the government. The managing director of the government broadcaster issued the notice of suspension.

In 2019, Neville Choi, then head of news for EMTV, was sacked for disobeying orders not to run a story of a military protest outside the Prime Minister’s office in Port Moresby. Choi was later reinstated following intense public pressure and a strike by all EMTV journalists and news production staff.

Two years later, a similar scenario played out when 24 staff and EMTV’s head of news were sacked for protesting against political interference in the newsroom.

For many within the industry, licensing just gives the government better tools to penalise journalists who present an unfavourable narrative.

On paper, the government appears to be trying to remedy the desperately ailing journalism standards in PNG. But the attempt is not convincing enough for many.

Fraser Liu, an accountant by profession and an outspoken observer of national issues, says the courts provide enough of an avenue for redress if there are grievances and that an additional layer of control is not needed.

Liu said: “Media agencies and agents must be left alone to their own ends, being free from coercion of any sort, and if media reporting does in fact raise any legal issues like defamation, then the courts are the avenue for resolution. There is no shortage in common law of such case precedent. This is clearly an act by government to control media and effectively free speech.

“Government cannot self-appoint itself as a referee for free speech. Free speech is covered under our Constitution and the courts protect this basic right. The policy talks about protection of reporters’ rights. Again, what is this? They already have rights guaranteed by the Constitution.

Coming back to poor journalism standards, Minister Masiu, a former broadcast journalist himself, has been challenged on many occasions to increase investment into PNG’s journalism schools. It is a challenge he has not yet taken up despite the abundant rhetoric about the need for improvement.

The energy of government should be put into fixing the root problem contributing to the poor quality of the media: poor standards of university education.

Scott Waide is a journalist based in Lae, Papua New Guinea. He is the former deputy regional head of news for EMTV and has worked in the media for 24 years. This article was first published on the DevPolicy Blog and is republished here under a Creative Commons licence.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz