SPECIAL REPORT: By Max Uechtritz

On Saturday, 30 years ago in 1988, I smelled death for the first time – literally.

A sickening, almost suffocating, stench assaulted my nostrils in a dank cave where 21 men – 19 Kanak militants and two French military – had been killed the previous day in what lives on infamously as the “Ouvéa Island massacre” in New Caledonia.

Our feet sunk deep into the loose layer of moist loam the gendarmes had shovelled from the jungle outside onto the cave floor to cover the blood and waste of the dead.

On what we trod it was impossible to know. I dry retched.

My ABC cameraman Alain Antoine, sound recordist Stewart Palmer and I were the very first of the first group of journalists to be allowed inside the Gossannah cave complex on Ouvéa where the Kanaks had died in an assault by French Special Forces.

We’d been flown from the capital Nouméa in a French military helicopter. As we’d scrambled onto the Ouvéa tarmac we bumped into a giant Kanak prisoner sporting red shorts, yellow T shirt and manacles being led the other way by French military (pictured below).

A Kanak militant being led away in handcuffs by French securiuty forces on Ouvéa Island in May 1988. Image: revolutionpermanente.fr

A Kanak militant being led away in handcuffs by French securiuty forces on Ouvéa Island in May 1988. Image: revolutionpermanente.fr

A few days earlier on the main island I experienced for the first of many times in my career the shock of having a cocked, loaded gun pointed at me. We’d happened upon the helicopter evacuation of a French officer wounded in an ambush. He later died.

Not worth shooting

A frightened, angry adrenalin-charged soldier raced up to our car screaming and pointing his automatic weapon before being calmed by a superior who chose to believe we were civilian journalists, not rebels and not worth shooting.

They were tense days.

The Ouvéa event is still cloaked in controversy (French President Emmanuel Macron visited Ouvéa yesterday for the 30th anniversary but, under pressure from families of the dead, refrained from laying a wreath at the graves of the 19 Kanaks).

The action and its context is described by respected Pacific author David Robie in Pacific Journalism Review (2012, pp. 214-215):

“I wrote the following in my book Blood on their Banner[1989, pp. 275-278] – the “blood” being that symbolised by the Kanak flag as being shed by the martyrs of more than a century of French rule:

“Mounting tension as the French security forces were built up in New Caledonia to 9500 for the elections finally erupted on Friday, 22 April 1988, two days before the poll. Kanak militants, arguably the first real guerrilla force in the territory, seized a heavily armed Fayaoué gendarme post on Ouvéa, in the Loyalty Islands.

“Armed with machetes, axes and a handful of sporting guns hidden under their clothes, they killed four gendarmes who resisted, wounded five others and seized 27 as hostages.

“They abducted most of their prisoners to a three-tiered caved in rugged bush country near Gossanah in the north-east of the island; the rest were taken to Mouli in the south.

As almost 300 gendarmes flown to Ouvéa searched for them, the militants demanded that the regional elections be abandoned and that a mediator be flown from France to negotiate for a real referendum on self-determination under United Nations supervision. They threatened to kill their hostages if their demands were not met.

“Declaring on Radio Djiido that he was dismayed by the attack, Tjibaou blamed it on the “politics of violence” adopted by the Chirac government against the Kanak people.

“‘The [colonial] plunderers refuse to recognise their subversive lead,’ he said. ‘From the moment they stole our country, they have tried to eliminate everybody who denounces their evil deeds. It has been like that since colonialism began.’

Appeal for calm

“(French President) Mitterrand appealed for calm and a halt to spiral of violence; (Premier) Chirac condemned the ‘savage brutality’ of the attack, claiming the guerrillas were ‘probably full of drugs and alcohol’.

“The guerrillas freed 11 hostages but remained hidden in their Wadrilla cache with the others. Another hostage, who was ill, was later released.

“[French Minister for Territorial Affairs Bernard] Pons portrayed the guerrilla leader, Alphonse Dianou, as a ‘Libyan-trained religious fanatic’. In fact, he had trained at a Roman Catholic seminary in Fiji and was regarded by people who knew him as ‘a reflective man, found of books and non-violent’. He spent hours explaining to his captives why they had been seized.

“At dawn on Thursday, May 5, French military and special forces launched their attack on the Ouvéa cave and killed 19 Kanaks in what was reported by the authorities to be a fierce battle. The hostages were freed for the loss of only two French soldiers.

“If the military authorities were to be believed, their casualties were from the 11th Shock Unit of the DGSE. (This unit was formerly the Service Action squad, used to bomb the Rainbow Warrior in Auckland Harbour on 10 July 1985).

“The assault came just three days before the crucial presidential vote, and hours after three French hostages had been freed in Lebanon following the Chirac government’s reported payment of a massive ransom.

“To top it off, convicted Rainbow Warrior bomber Dominique Prieur, now pregnant, was repatriated back from Hao Atoll to France.

Massacre ‘engineered’

Leaders of the [pro-independence] FLNKS immediately challenged the official version of the attack. Léopold Jorédie issued a statement in which he questioned how the “Ouvéa massacre left 19 dead among the nationalists and no one injured” and the absence of bullet marks on the trees and empty cartridges on the ground at the site”.

Yéiwene Yéiwene insisted that at no time did the kidnappers intend to kill the hostages – ‘this whole massacre was engineered by Bernard Pons who knew very well there was never any question of killing the hostages”. Nidoish Naisseline also condemned the action:

“Pons and Chirac have behaved like assassins. I accuse them of murder. They could have avoided the butchery. They preferred to buy votes of [Nationalist Front leader] Le Pen’s friends with Kanak blood.”

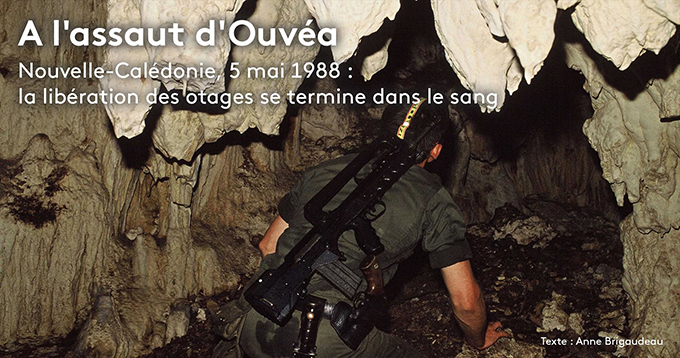

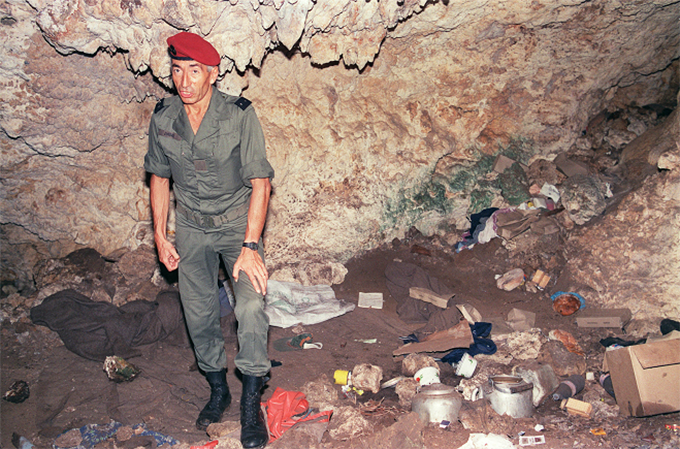

The Ouvéa assault on 5 May 1988.

The Ouvéa assault on 5 May 1988.

The following extract sums up claims and counter claims:

According to a later report of Captain Philippe Legorjus, then GIGN leader: “Some acts of barbarity have been committed by the French military in contradiction with their military duty”. In several autopsies, it appeared that 12 of the Kanak activists had been executed and the leader of the hostage-takers, Alphonse Dianou, who was severely injured by a gunshot in the leg, had been left without medical care, and died some hours later. Prior to this report, Captain Philippe Legorjus was accused by many of the GIGN agents who took part in the operation of weaknesses in command and to have had “dangerous absences” (some even said he fled) in the final stages of the case. He was forced to resign from the GIGN after this operation, since nobody wanted him as chief and to fight under him anymore.

The military authorities have always denied the version of events given by Captain Philippe Legorjus. Following a command investigation, Jean-Pierre Chevènement, Minister of Defence of the Michel Rocard government, notes that “no part of the investigation revealed that there had been summary executions”. In addition, according to some participants of the operation interviewed by Le Figaro, no shots were heard on area after the fighting ended.

Legorjus said French Premier Jacques Chirac, who was challenging Mitterrand in the French presidential elections, wanted to stage the assault. And Pons said that he had acted throughout the drama on the orders of Chirac, who believes the “separatist” movement should be outlawed.

Radio NZ on Saturday: “The two-week hostage crisis in 1988 was a turning point in the separatist campaign of the indigenous Kanaks because it ushered in reconciliation talks, which led to the 1988 Matignon Accord.

The Accord and its subsequent 1998 Noumea Accord allowed for the creation of a power-sharing collegial government and the phased and irreversible transfer of power from France to New Caledonia.”

Whatever the truth, the blood of 1988 will stain this territory for a long time yet.

Max Uechtritz is managing director of Kundu Productions Pty Ltd and is republished by Asia Pacific Report with permission. Photos thanks to France TV Outre-Mer and revolutionpermanente.fr

References:

Robie, D. (2012). Gossanah cave siege tragic tale of betrayal. Pacific Journalism Review, 18(2), 212-216.

Robie, D. (1989). Blood on their banner: nationalist struggles in the South Pacific (pp. 275-280). London, UK: Zed Books.

Inside the Gossanah cave on Ouvéa.

Inside the Gossanah cave on Ouvéa.

Southern Cross radio comment about the Ouvéa visit on 5 May 2018 by President Macron.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz

]]>