Keith Rankin Analysis.

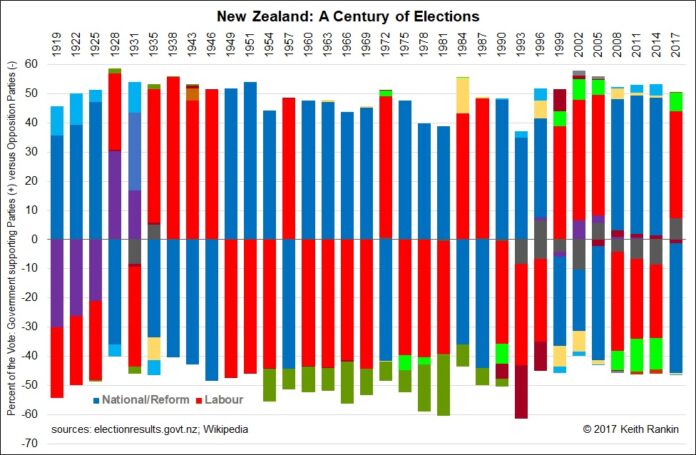

In 2017, the popular vote for the parties supporting the government is just over 50 percent – as it has always been since proportional representation was introduced 1996.

Before 1996 it was another story. After 1951, only 1972 and 1984 showed majority popular support for the resulting government. However, there was a block of elections from 1925 to 1951 in which popular support for the government exceeded 50% (with a proviso around John A Lee’s Labour breakaway party in 1943).

Of the post-war FPP elections, popular support for the resulting government was especially weak in 1954, 1966, 1978, 1981 and (most of all) 1993.

We must note that Independents always played a role upto 1935, much as they have done in Australia this century. I have used light blue for conservative Independents (and for Christian/Conservative parties in recent years). And I have used dark grey for Labour-supporting Independents (and for New Zealand First in recent years).

Of particular interest among the earlier elections are 1928 and 1931. In 1928 the party that had been third in 1925 (United, the rump of the Liberal Party of John Ballance, Richard Seddon and Joseph Ward; and led, from September 1928, by the now 72-year-old Ward).

In 1928 Reform, the principal precursor of National, had more votes than United but was tied on seats (27 each). United was able to form a government with Labour support on confidence and supply. It was Labour’s first taste of power. The arrangement did not last; it was Ward’s death in 1930 that revealed that United without Ward was really a very conservative party. (The global economic depression took hold in New Zealand in the second half of 1930.)

In 1931, Labour had more votes than any other party, and had increased its vote. But Labour was well short of a majority. A conservative coalition of United (3rd place) and Reform assumed power. United’s leader (George Forbes) continued as Prime Minister. Indeed, in all three elections which Forbes contested as leader of his party (1925, 1931 and 1935) his party had come third. Further, Forbes was instrumental in the postponement of the 1934 election, a situation that we would not tolerate of Jacinda Ardern and her government.

The chart is necessarily presented, on two dimensions, in a binary format. We should not presume the popular opposition to these governments as a united opposition, given the presence of independent MPs and independent parties such as Social Credit and New Zealand First.

Social Credit (shown in dark green) was never in government until, in the 1990s, it joined the Alliance (shown in dark red). Likewise, New Zealand First (in dark grey) is, with one exception, shown as ‘opposition’ unless a part of government. In 2005, a New Zealand First vote was not a vote for a Don Brash National change government. In 2017 a vote for New Zealand First was either a vote for ‘change’ or for a ‘substantially modified’ status quo. The exception is 1996, where there was no status quo, as it was New Zealand’s first MMP election. So, in 1996 I have split the New Zealand First support between government and opposition.

The Māori Party formed from Labour, in opposition to Labour. In the public mind it was been widely seen as ‘brown National’, and it was on that basis that it was not returned to Parliament in 2017. So here I have depicted the Māori Party (from 2005) as pro-National. This acts as a counterweight to the depiction of New Zealand First since 2005 as pro-Labour.

There is nothing exceptional about the present governing arrangement. Indeed, it’s what most people (at least in the media) expected to be the outcome in 1996. Multiparty government is not only associated with proportional representation. It has also been the reality in the United Kingdom for most of this decade. And it is a common reality in Australia.

Will the new government last until the next scheduled election year? Probably. 1928 and 1996 provide examples of a governing arrangements that did not last, even though in each case the Prime Minister was throughout the leader of the same party. We have to go back more than 100 years – to 1912 – to find a case when a Leader of the Opposition became Prime Minister mid-term. The 1912 situation can and will happen again, probably in the next twenty years. It nearly happened in 1998.