The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By John Long, Strategic Professor in Palaeontology, Flinders University

How can the development of motorcycles have anything to do with the story of the evolution of life on Earth? You need a palaeontologist to help answer that question, and one with a love of motorcycles.

The article is part of our occasional long read series Zoom Out, where authors explore key ideas in science and technology in the broader context of society and humanity.

Thousands of people around the world will don some of their finest clothes and ride motorcycles this weekend in the Distinguished Gentleman’s Ride. The goal is to raise funds and promote awareness of men’s health issues.

I’m taking part, having been a motorcycle enthusiast since I got my first bike in 1975. Motorcycles are great fun, but there’s also a lot you can learn from riding one.

John Long on his motorcycle. John Long, Author providedThe late author Robert M Pirsig’s 1974 classic book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance exemplified this perspective. Pirsig contrasts the rational and romantic sides of human nature as he describes his motorcycle journey of self-discovery.

Read more: Curious Kids: How many dinosaurs in total lived on Earth during all periods?

I’ve recently been contemplating similarities between the evolution of life and the early development of motorcycles, and what a motorcycle ride can teach us about the history of life.

A ride across Australia shows the deep time of evolution

The oldest life on Earth is shown in fossils of stromatolites, mounds of layered mats of blue green algae found in the Pilbara district of Western Australia, dated at around 3,500 million years ago.

Today similar life forms can be seen thriving in Shark Bay and in some of the estuarine lakes around WA.

Living colonies of stromatolites at Shark Bay in Western Australia. Dr Ken McNamara, Author providedBy sheer coincidence, the distance from Perth to Melbourne is about 3,500km, a route I travelled on my motorcycle back in 1996. Thus, every kilometre I did on that transcontinental ride represents a million years of Earth’s history since life first evolved. Thus, every metre represents a millennium, and every millimetre a year.

Let’s use this metaphor of time and distance to highlight the big milestones of the evolution of life on such a ride. Travelling along at 100kmh we’d pass through 100 million years of Earth history each hour of riding.

If we are at the origin of life in Perth (at 3.5 billion years ago), the next milestone we encounter is the development of cells with a nucleus, or eucaryotes. These appeared about 2 billion years ago, which on our ride would be around Ceduna in South Australia.

Not much happens until we cross the border into South Australia. Flickr/Brian Yap, CC BY-NCThe dawn of complex multicellular animal life (called metazoans), is seen by our famous Ediacaran fossils of the Flinders Ranges. Recent research has just proven these are the oldest true animals. This event – dated at around 560 million years ago – is the equivalent of arriving at the town of Keith, South Australia, on our ride.

If we deviate south and travel into the Coonawarra, famous today for its fine wines, we reach the time of the great Cambrian explosion of life, starting about 540 million years ago. This is when nearly all the major groups of marine animals appeared on Earth.

How a ride across Australia (about 3,500km) translates into a true analogy of evolutionary deep times, where 1km of travel represents 1 million years of time passing. John Long, Flinders University, Author providedThe origin of backboned animals (vertebrates) is another milestone represented by appearance of the first fishes. This happens as we drive across the border into Victoria on the road to Casterton.

Fishes left the sea and invaded land as early four-limbed tetrapods by the time we reach Hamilton, and we enter the age of dinosaurs and the first mammals as we cruise the backroads into Skipton, about 230 million years ago.

If our journey is to end precisely at the Melbourne Post Office (GPO) on Elizabeth Street, then the appearance of our immediate human ancestors, the australopithecines, will occur at a spot on the road about 3.5km from the GPO, on State Route 30.

Approaching the Melbourne GPO building. Wikimedia/Donaldytong, CC BY-SAWe park the bike near the GPO and walk towards it. Modern humans (Homo sapiens) appeared on Earth about 315,000 years ago, or just 315 metres from our destination. To mark the point in time when the first peoples arrived in Australia, around 60,000 years ago, we reach a point just 60 metres from our final destination.

Finally, we take five large steps, each a metre, to reach the front door of the GPO and in this final act we’ve gone through most of recorded human civilisation, taken from the first step pyramid of Djoser about 5,000 years ago in Egypt, to today.

You have reached your destination – The Melbourne GPO building is now a shopping centre. Flickr/, CC BY-NC-SAThe rate of evolution of life compared with early motorcycles

As a palaeontologist who studies life of the past, I see evolution in action all around me. Not just in species of animals and plants that have adapted as their environments, but also through fossil species that couldn’t adapt and went extinct.

I’m now going to explore the metaphor of how the history of motorcycle development shows a similar tempo for diversification as that of early life, even if it is on a totally different scale of time.

Motorcycles, like life, had a long, slow history of development – followed by sudden explosions of innovative engineering diversification. Let’s arbitrarily start the clock from the invention of the first atmospheric combustion engine, the Newcomen steam engine, in 1712.

Early steam-driven motorcycles, such as Sylvester Roper’s steam velocipede, were hazardous, as the metal boiler building up pressure was positioned between the rider’s legs – not something our safety advisers would like today.

The Roper steam velocipede, an early steam-powered motorcycle (c 1886). WikimediaThe machine could run at speeds of 64kmh for up to an hour, becoming the first non-railed machine that could power a human at far greater speeds than just running.

The next major milestone is the creation of the fuel-air compressed combustion engine by Beau de Rochas in 1862. Our modern four-stroke engine was developed by Nicklaus Otto around 1864 with help from Eugen Langden.

The first motorcycle

The first ridden two-wheeled machine with handlebars and a combustion engine powered by this engine was Wilhelm Maybach and Gottleib Daimler’s Reitwagen or “riding car” – considered to be the world’s first motorcycle.

A test vehicle for the high-speed four-stroke engine invented by Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach. The ‘riding car’ is also considered the world’s first motorcycle. DaimlerThe first trial ride was particularly exciting, as Daimler’s son Paul, aged 17, drove it for 12km on November 18, 1885. It was an unexpectedly eventful journey as the rider’s seat caught fire due to the hot tube ignition system wedged immediately below it.

It took another decade before Hildebrand and Wolfmuller of Germany would commercially produce a powered motorcycle that was freely available on the open market in 1894.

Just like the sudden Cambrian explosion of life, the next few years saw a sudden great explosion of motorcycle diversity as expressed by varied engine types – a time when efficient four-stroke combustion engines of many kinds and varieties were fitted into strengthened bicycle-type frames.

Motorcycles of nearly all modern configurations then suddenly appeared between 1900 and 1912 from manufacturers in England, Europe and the United States.

Varied engine positions were trialled, from up high on the handlebars, or attached to either the front or rear wheels, but eventually the engine position stabilised (evolved) in a slung frame at the centre of the bike.

The 300cc Cyclon made in Berlin (1900) had the engine mounted above the handlebars. Many experimental bike designs were trialled. John Long, with permission of NSU Museum, Neckarsulm, Germany, Author providedWe find examples of single-cylinder engines of many types (vertical, sloping, horizontal), twin engines (upright, in line V-twin, transverse and inline; flat horizontal twins), radial engines, even three and four cylinder engines.

The first working two stroke engine bikes were commercially available in 1908. The British motorcycle manufacturer Humber had an electric-powered bicycle on the scene around 1897. Even the first rotary engine motorcycle, invented by Felix Millet in 1889, went into production in 1900.

The 1912 Verdel 5 cylinder radial engine motorcycle. John Long, with courtesy Sammy Miller Museum, UK, Author providedRates of evolution: motorcycles vs early life

I’m now going to measure the rate of motorcycle evolution from the first atmospheric combustion steam engine in 1712 through to an arbitrary milestone in the 20th century that represents the emergence of the first highly complex modern motorcycle.

I’m choosing the appearance of Guilio Carcano’s V8 double overhead cam 499cc Moto Guzzi racer of 1955 to represent the dawn of the modern superbike.

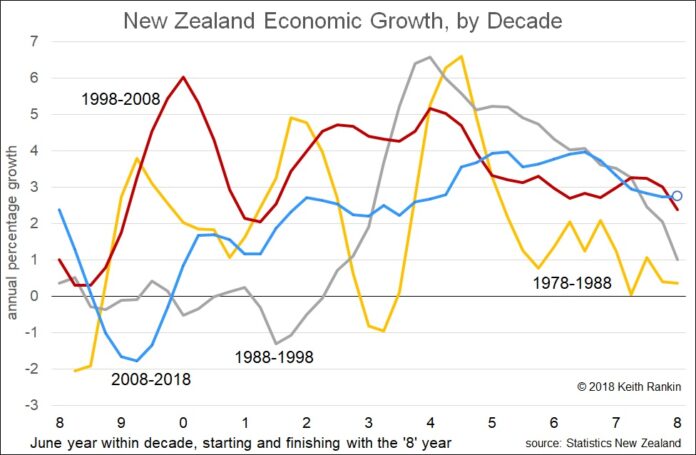

A 1955 Moto Guzzi V8 (500cc), perhaps the world’s first superbike, at the Moto Guzzi Museum, Mandello Del Lario, Italy. John Long, Author providedUsing this analogy, the time and tempo for motorcycle development (scaled between 1712-1955) follows a very similar pattern of diversification as the evolution of life over 3.5 billion years.

Since the invention of the first steam engine in 1712, it took about 160 years for the first steam-driven motorcycle to appear (about 62% of the time), and 182 years until the first commercial combustion-engine motorcycles were sold in 1894 (about 75% of the time).

Read more: Life on Earth still favours evolution over creationism

The peak of early motorcycle diversification at around 1908 took place at exactly 80% of the time elapsed, almost exactly at the same time ratio as the Cambrian explosion of life took place since life first appeared on Earth.

A comparison showing the long slow development and then sudden diversification of life (top) with a similar pattern for the development of the combustion engine and motorcycle diversification (below). John Long, Author providedUncanny similarity perhaps?

I can probably find other comparison tales in the development of aircraft, ships, trains, cars or in any form of technology. But it’s a good example of how transdisciplinary knowledge can inform two disparate topics, seemingly not related, but with learning benefits on each side.

Something to think about next time you see or ride a motorcycle.

On the road! Flickr/Su Yin Khoo, CC BY-NC-SAOn Sunday September 30, 2018, more than 120,000 gentlefolk in 650 cities worldwide will take part in the Distinguished Gentleman’s Ride to raise funds and awareness for men’s health.

– What evolution and motorcycles have in common: let’s take a ride across Australia– http://theconversation.com/what-evolution-and-motorcycles-have-in-common-lets-take-a-ride-across-australia-95880]]>

Papuan protesters arrested at a separate demonstration in Timika. Image: Voice Westpapua

Papuan protesters arrested at a separate demonstration in Timika. Image: Voice Westpapua