Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By John Quiggin, Professor, School of Economics, The University of Queensland

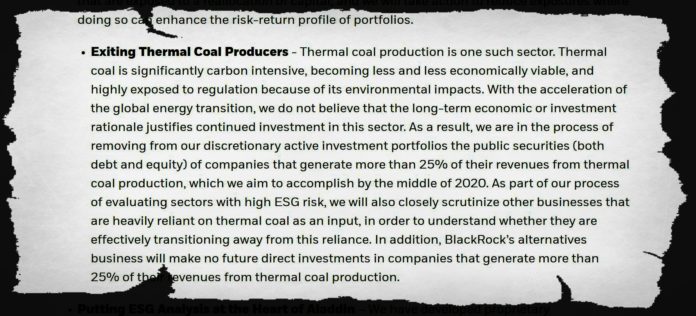

The announcement by BlackRock, the world’s largest fund manager, that it will dump more than half a billion dollars in thermal coal shares from all of its actively managed portfolios, might not seem like big news.

Announcements of this kind have come out steadily over the past couple of years.

Virtually all the major Australian and European banks and insurers, and many other global institutions, have already announced such policies.

According to the Unfriend Coal Campaign, insurance companies have stopped covering roughly US$8.9 trillion of coal investments – more than one-third (37%) of the coal industry’s global assets, and stopped offering reinsurance to 46% of them.

Blackrock matters because it is big

The announcement matters, in part because of Blackrock’s sheer size.

It is the world’s largest investor, with a total of $US7 trillion in funds under its control. Its announcement it will “put climate change at the center of its investment strategy” raises questions about the soundness of smaller financial institutions that remain committed to coal and to a carbon-based economy.

Blackrock is also important because its primary business is index funds, that are meant to replicate entire markets.

So far these funds are not affected by the divestment policy. BlackRock’s iShares United States S&P 500 Index fund, for instance, has nearly US$23 billion in assets, including as much as US$1 billion in energy investments.

But the contradiction between the company’s new activist stance and the passive replication of an energy-heavy index such as Australia’s is obvious. The pressure to find a solution will grow.

In time, the entire share market will be affected

One solution might be for large mining companies such as BHP to dump their coal assets in order to remain part of both Blackrock’s actively managed (stock picking) and passively managed (all stocks) portfolios.

Another might be the development of index funds from which firms reliant on fossil fuels are excluded. It is even possible that the compilers of stock market indexes will themselves exclude these firms.

The announcement has big implications for the Australian government.

Read more: Fossil fuel campaigners win support from unexpected places

Blackrock chief executive Laurence Fink noted that climate change has become the top issue raised by clients. He said it would soon affect all all investments – everything from municipal bonds to mortgages for homes.

Once investors start assessing government bonds in terms of climate change, Australia’s government will be in serious trouble.

Australia’s AAA rating will be at risk

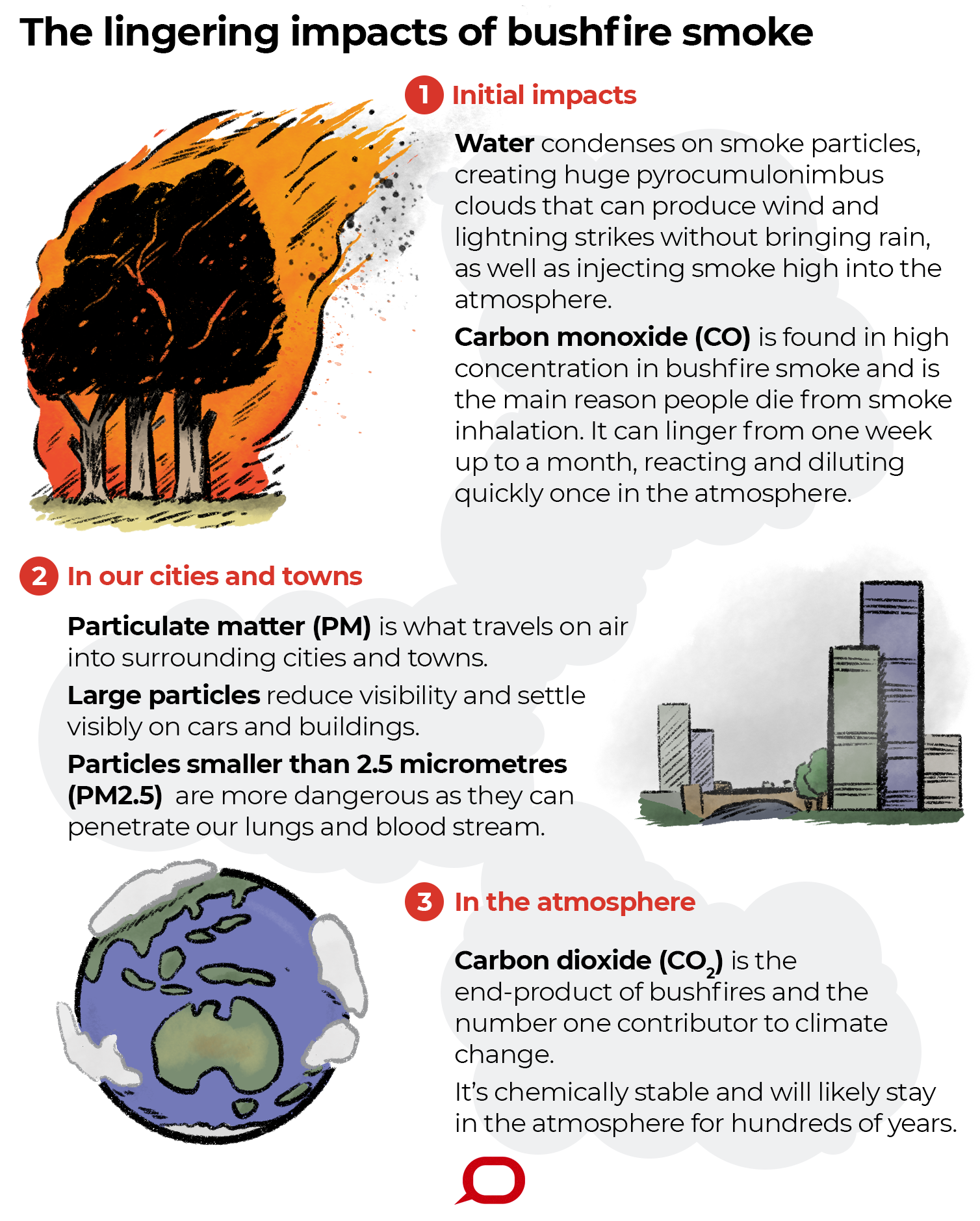

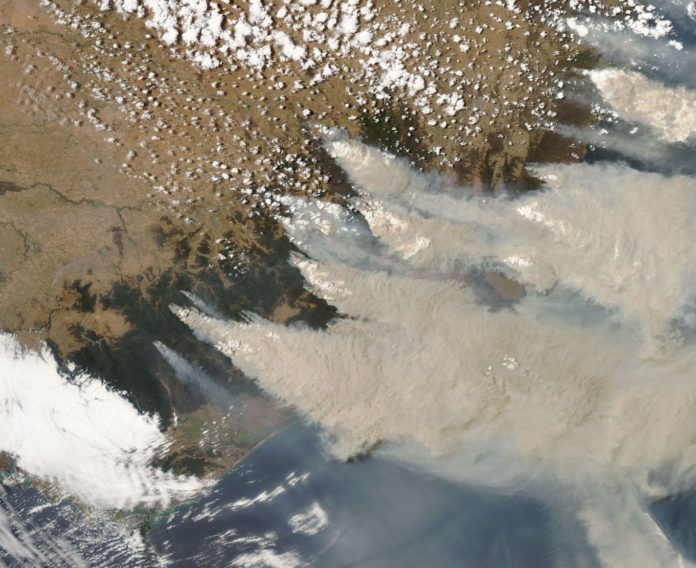

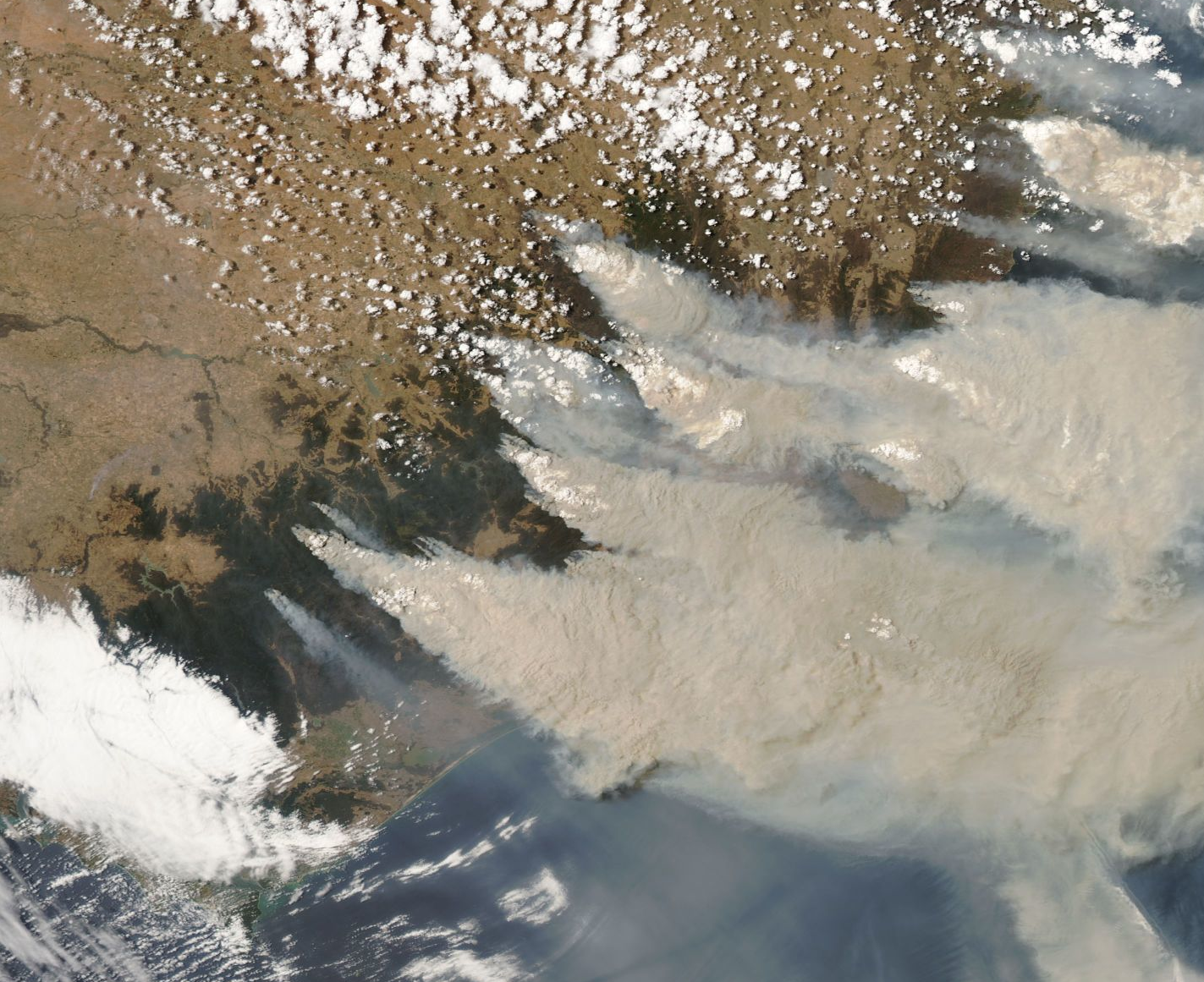

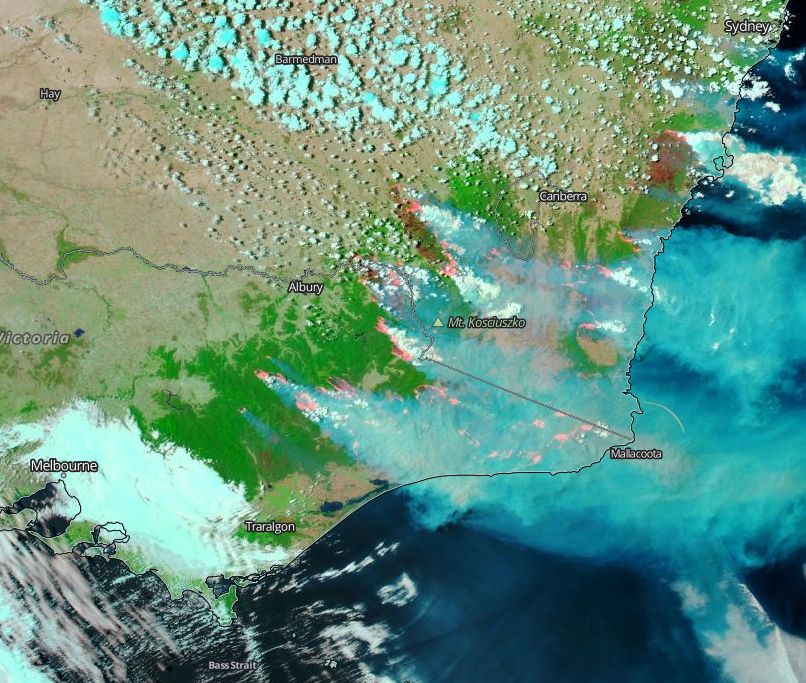

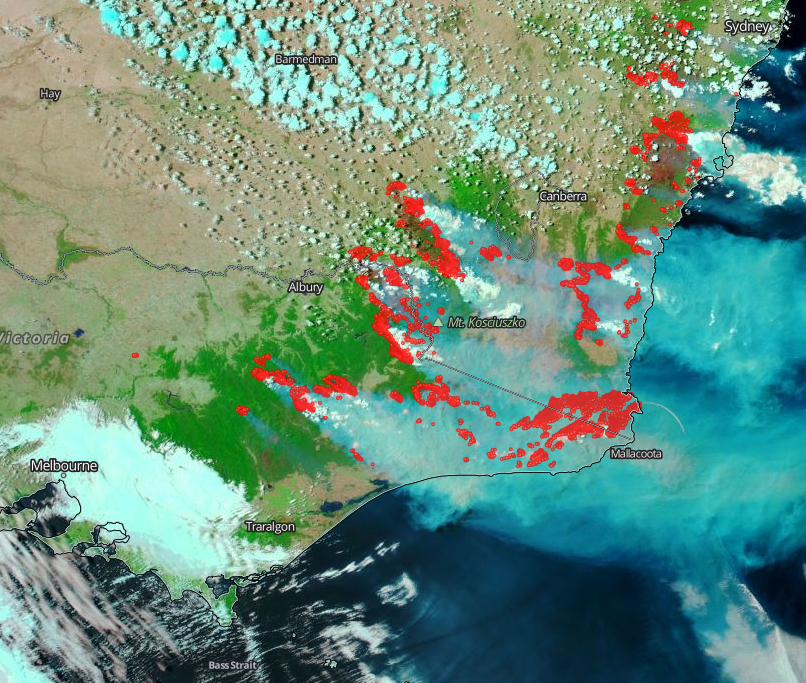

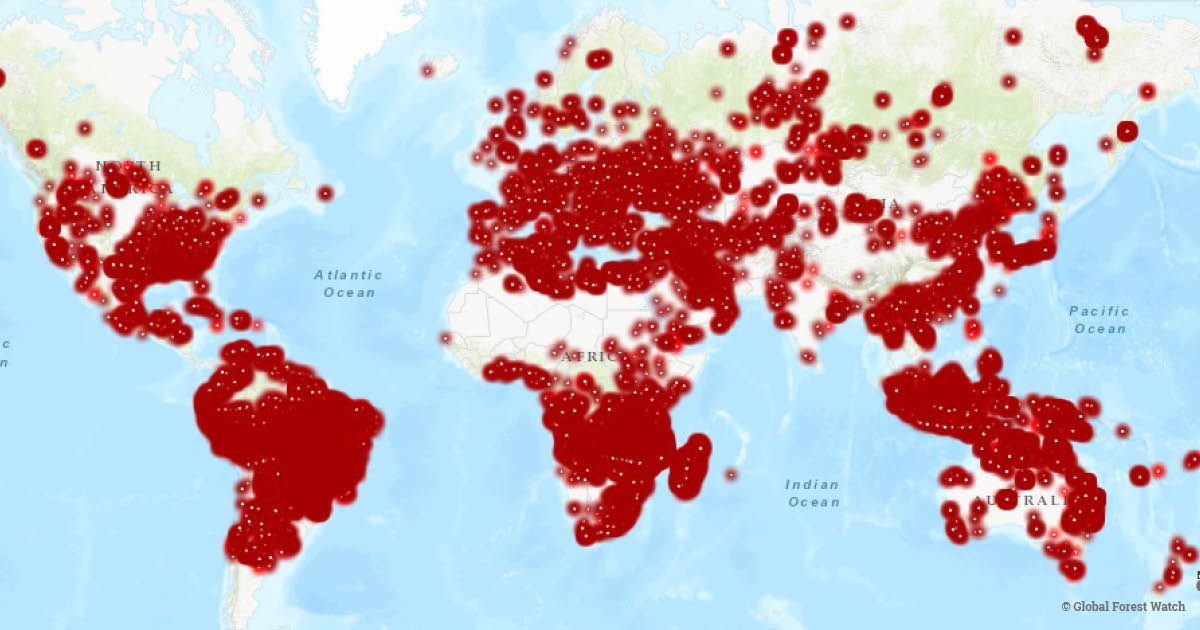

The bushfire catastrophe and the government’s inadequate response have shown the world Australia is both among the countries most exposed to climate catastrophe and one of the worst in terms of contributions to solutions.

Once bond investors follow the lead of Blackrock and other financial institutions, divestment of Australian government bonds will follow.

This process has already started, with the decision of Sweden’s central bank to unload its holdings of Australian government bonds.

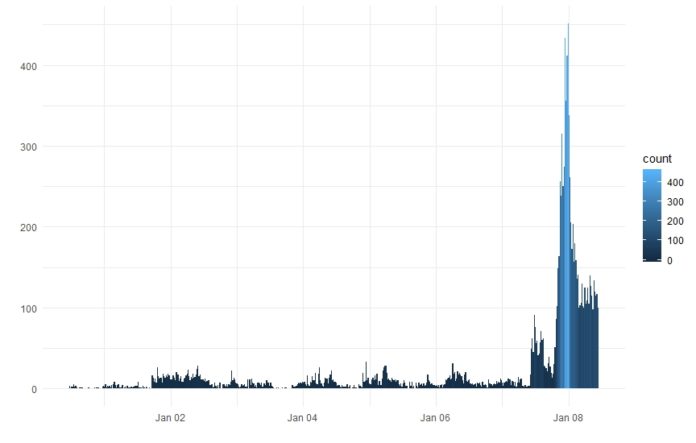

Taken in isolation, Sweden’s move had virtually no effect on Australia’s bond prices and yields. But the most striking feature of the divestment movement so far is the speed with which it has grown from symbolic gestures to a severe constraint on funding for the firms it touches.

Read more: Climate change: why Sweden’s central bank dumped Australian bonds

The fact that the Adani corporation was unable to find a single bank willing to fund its Carmichael mine is an indication of the pressure that will come to bear.

The effects might be felt before large-scale divestment takes place. Ratings agencies such as Moody’s and Standard and Poors are supposed to anticipate risks to bondholders before they materialise.

It’ll make inaction expensive

Once there is a serious threat of large-scale divestment in Australian bonds, the agencies will be obliged to take this into account in setting Ausralia’s credit rating. The much-prized AAA rating is likely to be an early casualty.

That would mean higher interest rates for Australian government bonds which would flow through the entire economy, including the home mortgage rates mentioned in the Blackrock statement.

The government’s case for doing nothing about climate change (other than cashing in on past efforts) has been premised on the “economy-wrecking” costs of serious action.

But as investments associated with coal are increasingly seen as toxic, we run an increasing risk that inaction will cause greater damage.

– ref. BlackRock is the canary in the coalmine. Its decision to dump coal signals what’s next – http://theconversation.com/blackrock-is-the-canary-in-the-coalmine-its-decision-to-dump-coal-signals-whats-next-129972