Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Véronique Duché, A.R. Chisholm Professor of French, The University of Melbourne

Modern warfare produces both trauma and boredom in equal measure. During the first world war, one way troops found solace was by writing and reading magazines created by soldiers, for soldiers.

Throughout the war, these magazines were produced in trenches, on troopships, in camps and in hospitals. Some were written by hand; others produced on makeshift printing presses soldiers came upon in war-torn towns of France and Belgium.

They could be simple pencilled sheets reproduced with carbon paper or made using jelly or spirit duplicators. Others were more sophisticated multi-page publications, often featuring illustrations.

The Australian War Memorial holds 170 troopship journals and over 70 trench magazines. Many other trench publications have disappeared; some can’t be read anymore because their ink has faded.

Our research focuses on how these magazines cared for soldiers, considering their significant psychological and emotional benefits.Bran Mash and Aussie

One of the first Australian magazines was the Bran Mash, created by the 4th Australian Light Horse Regiment on Gallipoli.

Written in pencil on two leaves of official typing paper, and duplicated with carbon paper, there was only a single issue. It included a selection of the rumours, or “furphies”, circulating on Gallipoli.

Many trench journals published a single or limited number of issues. They were often forced to stop production because of troop movements, the loss of an editor or printing press, or lack of paper.

Phillip L. Harris, editor of trench magazine Aussie: the Australian Soldiers’ Magazine, once wrote he had made “a fortunate discovery in the cellar of a printery at Armentiéres”.

There, he found ten tons of paper, with which he printed 100,000 copies of the third issue of Aussie. With Harris at the helm, 13 issues of Aussie were produced in the Western Front trenches through 1918 and 1919.

These magazines all reflected the humour, sentiment and preoccupations of soldiers and soldier-patients. The handwritten The Dinkum Oil, produced at Gallipoli over eight editions in 1915 was a place to express national identity — not least through the use of Australian slang.

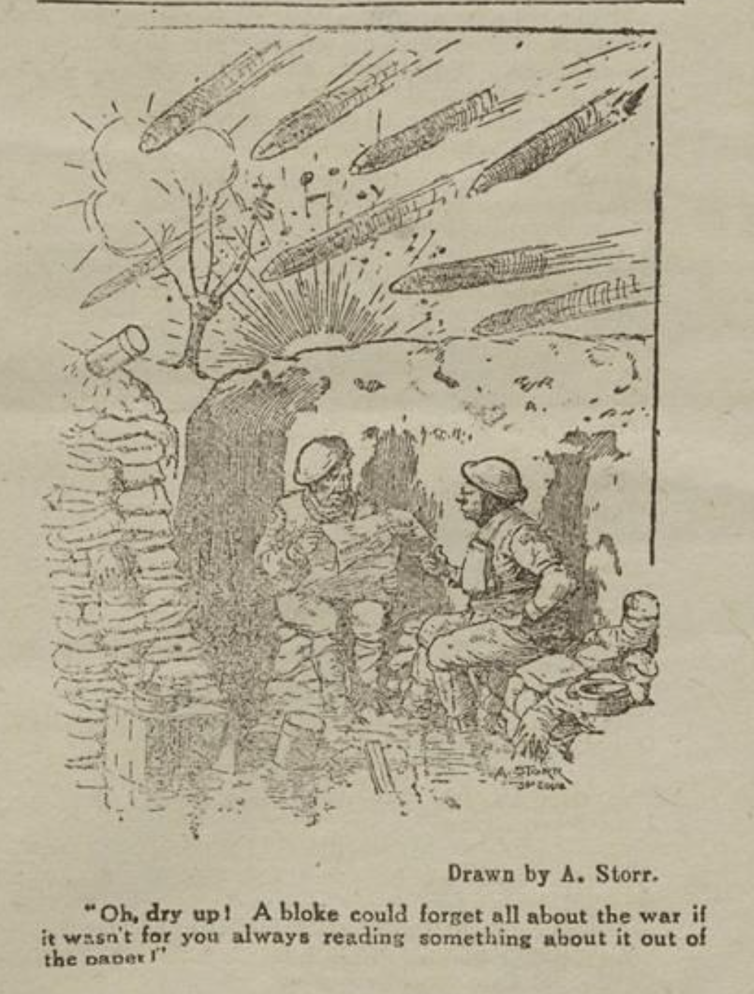

These magazines offered therapeutic value through their reading, and writing. Stories, verse and jokes were all welcome, alongside items airing complaints: a much-needed release valve for the disgruntlements of military life.

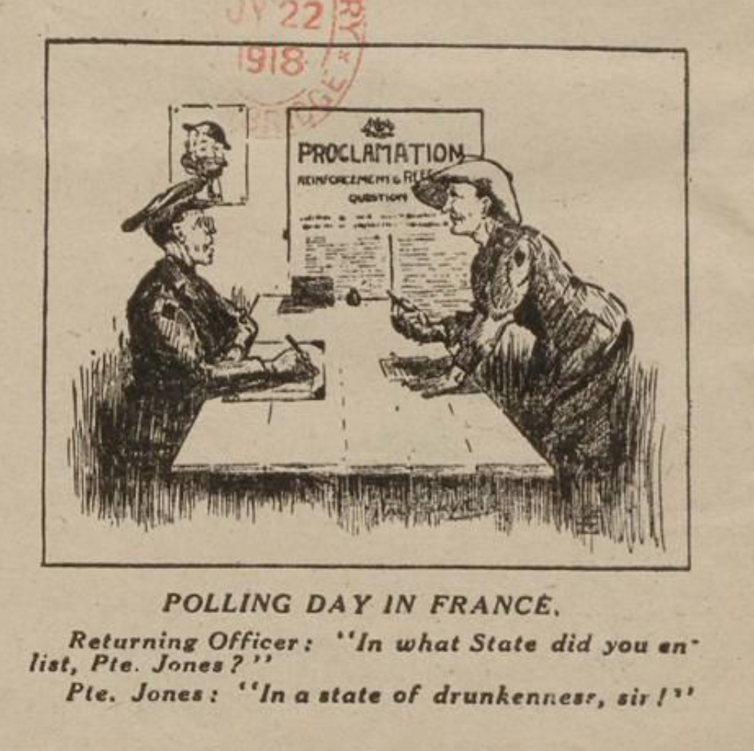

Humour runs through them. A cartoon in Aussie, captioned “Polling Day in France”, showed two officers talking. “In what State did you enlist?” asks the senior officer. Private Jones replies: “In a state of drunkenness, sir”.

Other anecdotes captured misunderstandings between the Australian soldiers and French civilians, with “bon soir” misheard as “bonza war!”

Read more: Peter Weir’s Gallipoli 40 years on: deftly directed and still devastating

Bright and light

The editors called for “bright, short contributions”, as The Rising Sun, an Australian magazine produced from December 1916 to March 1917, put it.

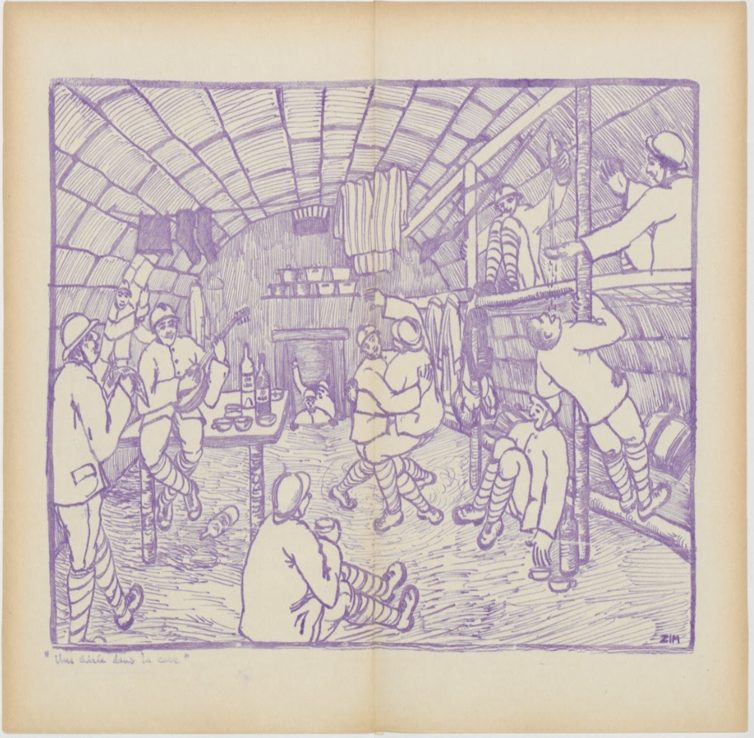

French trench magazine Le Poilu (“The Hairy One”, a slang term for an infantryman) stated its ambition as being “simply to entertain you for a moment, between two heavy mortar shells, or even between two fatigue-duties.”

The Harefield Park Boomerang, published at the No. 1 Australian Auxiliary Hospital at Harefield House in Middlesex, England, committed to having a “cheery tone”, despite the sometimes grim content of their publication.

Read more: Friday essay: do ‘the French’ care about Anzac?

Alongside news of activities in the hospital and updates on sports news, it included mentions of men who died (“our fallen comrades”) and their funeral details, as well as updates on donations to the “headstone fund appeal”.

Alongside the grim realities, black humour is very apparent. A poem in Mountain Mist, a magazine produced by soldier-patients at the Bodington sanitorium in the Blue Mountains for returned soldiers suffering tuberculosis, played on the popular soldier song Parlez Vous with words changed to reflect the experience of the tubercular soldier:

Digger had a little cough

It wasn’t much you know

Yet everywhere that Digger went

His cough it had to go.

Sentiment also figured strongly. Poems praising mothers and sisters were common, and there were many invocations of home.

In 1917, J.J. Collins wrote a poem “To my mother”, published in the Harefield Park Boomerang, comforting her he was not defeated by his wounds:

I’ll bring home marks of a German shell.

But what does it matter, mother dear?

Dry from your eye that glistening tear.

Let your heart rejoice at the pain I’ve borne.

These magazines were also sent home, giving loved ones a glimpse of war life.

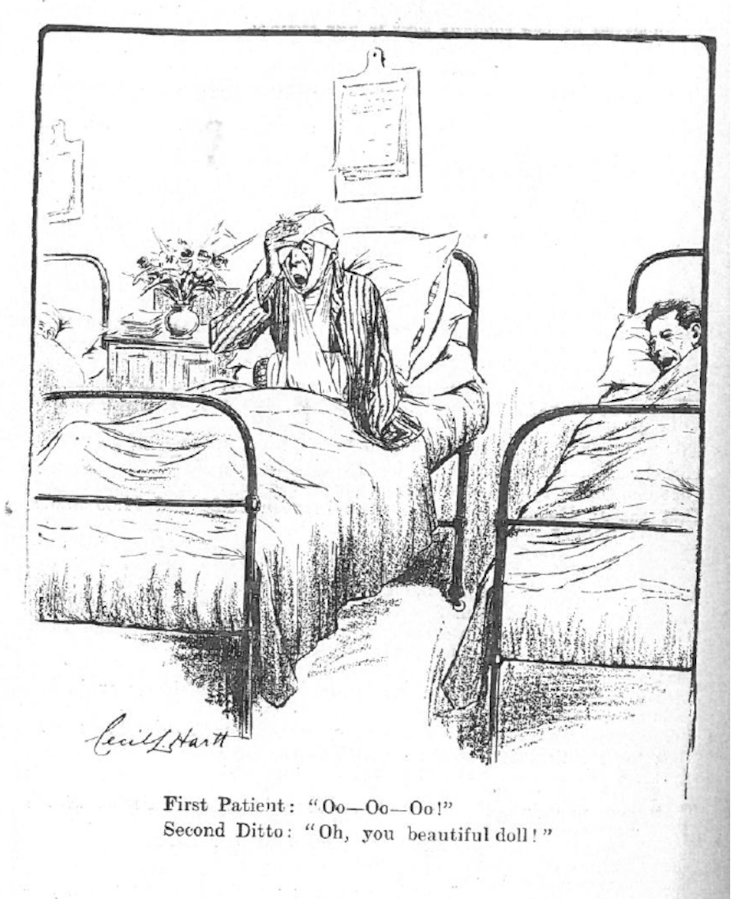

Hospital magazines could provide some reassurance to loved ones, but the picture they painted was incomplete. Soldier-patients were typically presented as stoic, cheerful and able to cope with whatever was thrown at them – as the poem by Collins shows.

But the reality for many returned soldiers who had been wounded would be a legacy of ill-health and early death.

For soldiers wounded in ways that would forever change them, this was perhaps how they preferred to be seen — still men, still warriors. These magazines reworked the traumas of war to try and make the experience palatable for the men, and for their loved ones.

Read more: Telling the forgotten stories of Indigenous servicemen in the first world war

Ongoing bibliotherapy

These early trench and hospital magazines played an essential psychological function. In providing entertainment and in keeping soldiers’ minds occupied, they were a much-needed form of therapy and mental comfort in difficult times.

The place these magazines held in soldiers’ hearts was perhaps illustrated in the reprinting of all the wartime editions of Aussie magazine in 1920.

Phillip Harris subsequently revived the paper, now to be a general newspaper that would transfer the “splendid spirit of comradeship, enthusiasm and patriotism” of the Australian soldiers to the Australian population at large. It lasted until 1931.

– ref. The comfort of reading in WWI: the bibliotherapy of trench and hospital magazines – https://theconversation.com/the-comfort-of-reading-in-wwi-the-bibliotherapy-of-trench-and-hospital-magazines-158880