Journalists already under threat of military arrest, jail and torture in Myanmar are now fronting a covid-19 national crisis as the virus rips through a country stripped bare, writes Phil Thornton.

SPECIAL REPORT: By Phil Thornton of the International Federation of Journalists

It is six months since Myanmar’s military began dismantling the institutional framework supporting the country’s fledgling democracy by propelling a deadly coup to wrest parliamentary control away from the newly-elected National League of Democracy (NLD) government.

Soon after the coup in February 2021, the military swiftly targeted voices of dissent and launched a deadly campaign of violence to silence critics. Rooftop snipers were ordered to shoot to kill, police and army raided homes of journalists, doctors, politicians and protesting citizens.

Independent media were outlawed and journalists were forced into hiding.

Critics of the “coup”, or even naming it as such in reporting or on social media, resulted in arrest warrants for breaches of section 505(a) of the Penal Code.

Non-profit human rights organisation Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP) confirmed as of August 4, 2021, the military had killed 946 people, including 75 children and arrested 7051 protesters.

Among them, seven health workers have been killed, another 600 doctors and nurses have arrest warrants issued against them, a further 221 medical students have been arrested and 67 medical staff are in detention.

AAPP reported the military has arrested at least 98 journalists, six of whom have been tried and convicted. Journalists may have gone into hiding for their safety, but this hasn’t stopped the military targeting and threatening their families.

A country in chaos

Myanmar is now in crisis. The economy has crashed. The already threadbare healthcare system has collapsed from the strain of the covid-19 pandemic.

Military restrictions prevent people receiving medical treatment, while doctors and nurses continue to be arrested for protesting against the coup. Meanwhile, people infected by the covid-19 virus face certain death via the military’s heartless restrictions on hospitals, oxygen and medicine.

Doctors who manage to work from clandestine pop-up clinics are exhausted by the huge surge in cases needing treatment.

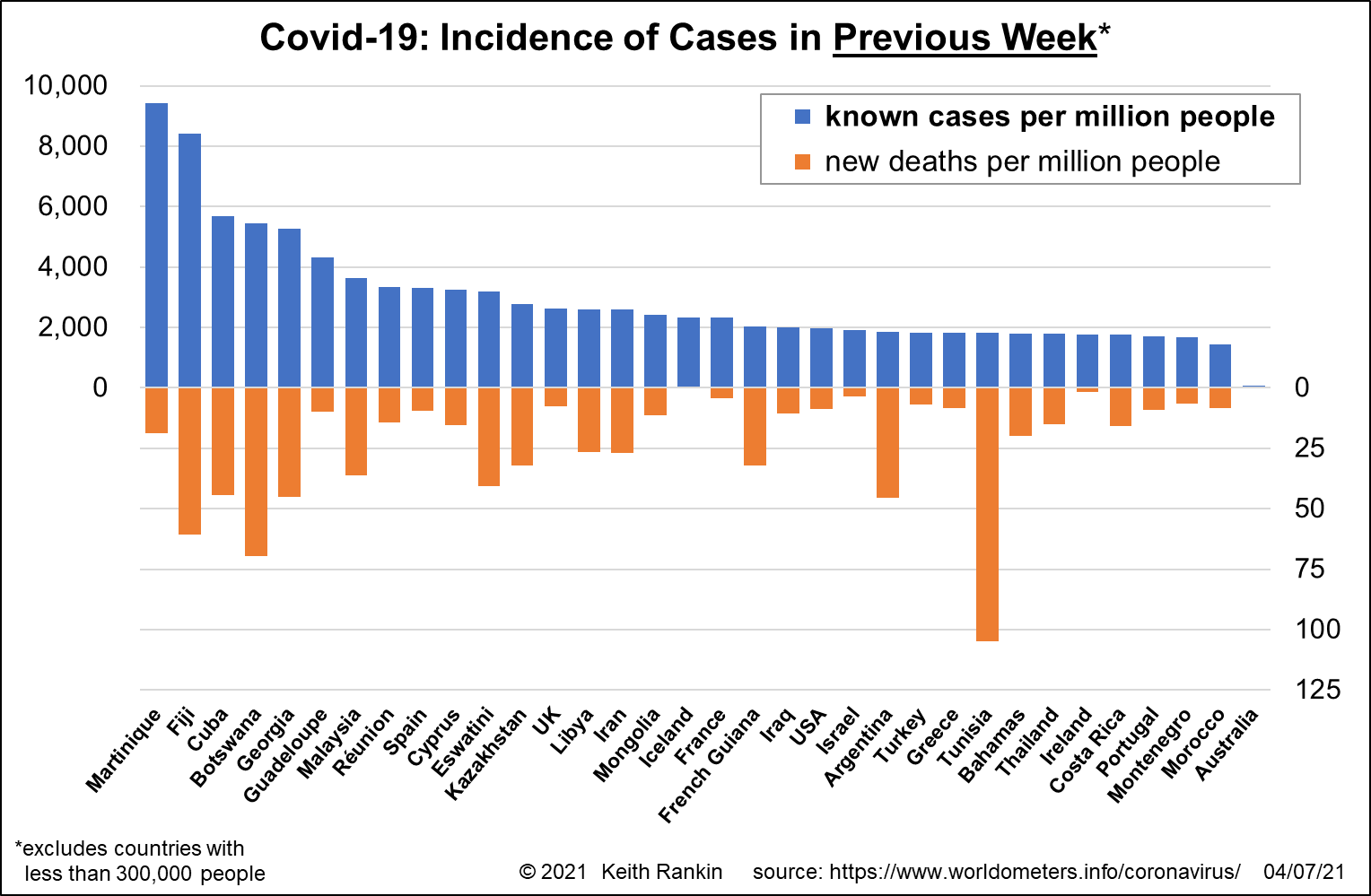

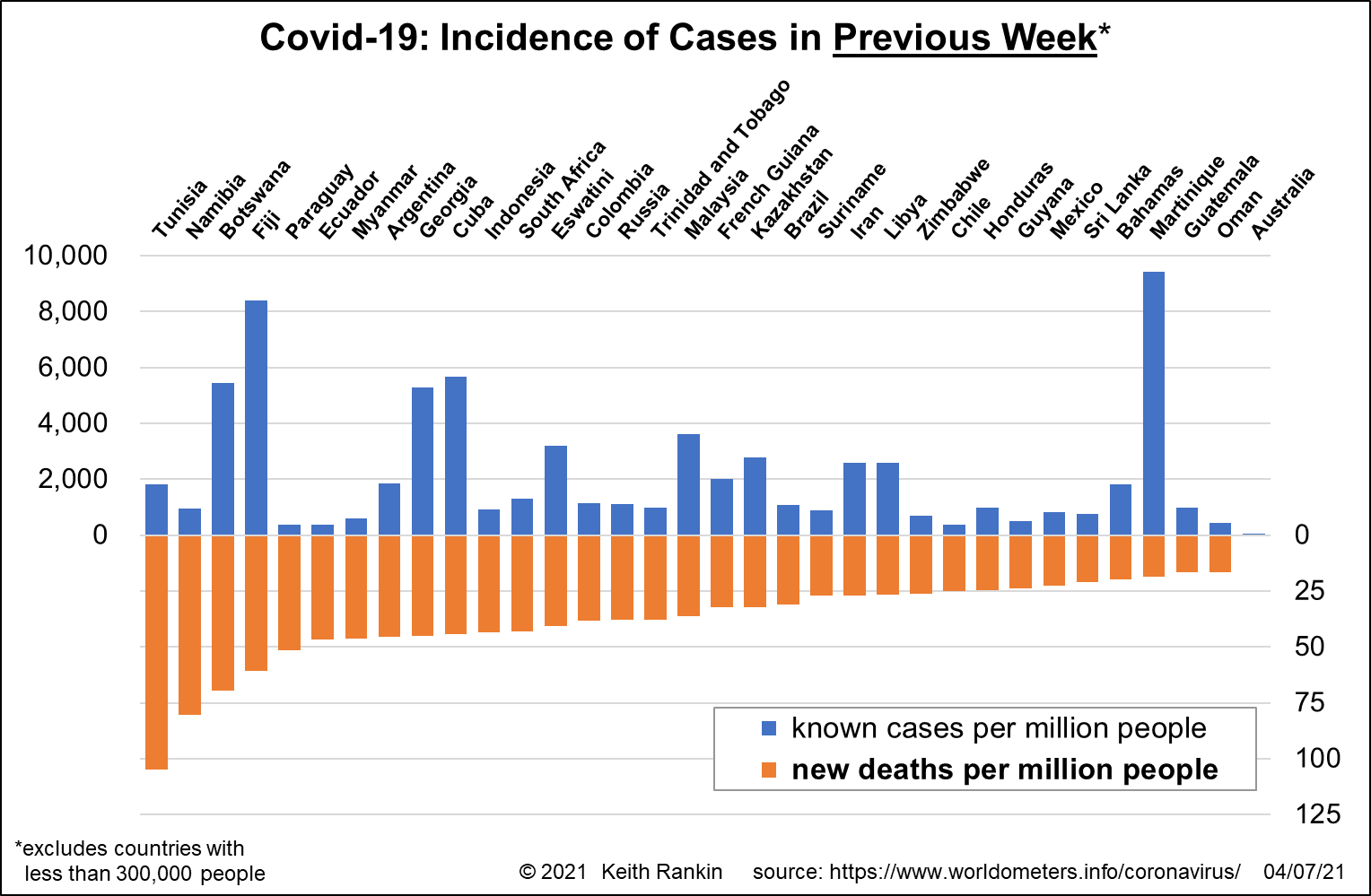

International health experts estimate as many as half the country’s population could become infected with the various covid-19 strains and the risk of death is high.

United Nation’s human rights expert Tom Andrews has urged Myanmar’s military at the end of July to join a “covid ceasefire” to combat the pandemic sweeping the country. But international pleas are unlikely to sway the military coup leaders or its puppet, the State Administration Council, now reformed as a caretaker government under the leadership of General Min Aung Hlaing as its so-called prime minister.

The military has a certain form when handling natural disasters — its strategy is to treat them as security threats. When Cyclone Nargis battered Burma on 2 May 2008, killing as many as 138,000 people and affecting at least another 2.4 million, the military’s response was to block international aid and jail those who reported on or tried to help storm victims.

The same strategy has been used with the ceasefires it negotiates with ethnic armed groups. A senior Karen National Liberation Army officer told the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) that ceasefires with the military produce little for the people.

“Our experience is they tie us up in endless meetings that yield little of value. They are a delaying tactic and we know they map our army positions and those of displaced people camps and later attack us as happened in March this year,” he said.

In March 2021, the Myanmar armed forces launched a series of airstrikes and ground attacks in ethnic regions that left as many as 200,000 villagers displaced. These people are now in desperate need of basic shelter, medicine, food and security.

The military’s go-to strategy is to block critical aid and medicine getting to displaced people and to jail and kill those it classifies as its enemies. Since the February coup, these “enemies” have included doctors, lawyers, politicians, community leaders, activists and journalists.

AAPP said people are now having to face the covid-19 pandemic with under-resourced hospitals and clinics with most unable to buy basic medicine from pharmacies that have run out of stock. Basic medicine is hard to find and expensive to buy.

The military is forcing public hospitals to close and is actively stopping people buying or refilling oxygen cylinders. Cemeteries and crematoriums are unable to cope with the huge numbers of fatalities, leaving corpses to pile up.

Through all this, the State Administration Council is accused by international, regional and opposition health professionals of withholding statistics and issuing false information.

‘I’m only doing my job’

Senior journalist Win Kyaw, who is now in hiding on the Myanmar border, spoke with IFJ about the ongoing difficulties of trying to keep reporting six months on from the coup.

“I fled my home months ago. I left everything behind. Now it’s much worse for journalists worried about catching covid. We can’t move around because of soldiers at checkpoints checking phones and who we are. It is very hard to keep going,” said Kyaw.

He said there is no way to counterbalance the false information and quackery remedies circulating among people desperate for ways to combat the virus.

“Before the coup, I reported the first and second wave freely. We only worried about catching the infection. Authorities willingly gave us data, information. Since the coup it’s the opposite.

“The military is trying to arrest us, we have to work secretly, we can’t get any information from authorities or our old sources. How can people make informed decisions about treatments and what medicines to take with all the misinformation being spread?”

Win Kyaw has an arrest warrant issued against him for what the military claims are breaches of section 505(a) of the Penal Code.

“I was only doing my job as a journalist, but they saw our news coverage as a threat. If we are not allowed to do our job uncensored at such a critical time it causes all sorts of problems. People need to know what to do and what not to do during the pandemic.

“We also know important stories putting the military under scrutiny need to be reported. For example, what’s happened to the US$350 million donated to the country by the International Monetary Fund (to help prevent covid)? It’s important accredited journalists cover these stories and we are allowed to do our job.”

Win Kyaw acknowledges the difficulty of confirming actual death rates from covid-19 as the State Administration Council reports are sanctioned and approved by military leaders.

“We know the military is restricting oxygen and medical supplies and jailing doctors. We know people are dying in their thousands.”

A recent incident involving a senior Myanmar Army officer highlighted the need to keep the spotlight on corruption, he said. The story the journalist is referring to involved Myo Min Naung, an army colonel who ordered the seizure of 100 oxygen cylinders crossing from Thai border town Mae Sot to Myawaddy on the Myanmar side.

Myo Min Naung first denied he had taken the cylinders but was later quoted in state-owned media saying he had only “borrowed” the oxygen for emergency use in Karen State hospitals.

“This is a clear case of abuse of authority,” says Win Kyaw. “It was clear the oxygen had the official paperwork and been ordered by a Yangon charity to treat covid patients. As far as we know the oxygen has not been returned.”

The journalist is convinced the military is deliberately using covid-19 against citizens.

“Government hospitals are full – they cannot take anymore covid-19 patients. People are forced to rely on home treatment. Knowing this, the military blocked people refilling oxygen cylinders for private use, restricted medicine and closed hospitals – the military is using covid-19 as a weapon to kill people.”

Win Kyaw has just recovered from fighting the virus while in hiding.

“It was hard. Out of our seven people in the household, four were sick. We had the symptoms, we couldn’t get tested, we didn’t know if it was the flu or covid. We were lucky … we could get oxygen, medical advice and medicine.”

Every journalist the IFJ has spoken to during the past six months since he coup has either been infected and or had a family member die.

Despite knowing the risks and the fact that the military is actively hunting him, Win Kyaw is determined to keep reporting.

“Most of us don’t get salaries now, as most independent media houses have been outlawed by the military, but we feel we have a duty to cover the news as best we can.

“We have to try to travel to confirm stories and this puts us at risk. We need money for masks and PPE, medicine and oxygen concentrators.”

When their media organisations’ operating licences were cancelled by the military, many independent journalists had to go underground or risk arrest. Without paid work many journalists resorted to selling their equipment – laptops, drones, voice recorders and cameras – keeping only the essentials needed to keep reporting.

People dying alone

Than Win Htut, a senior executive with the Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB), is still managing to send out regular daily reports despite having to hide on the border of a neighboring country.

Like other journalists interviewed, Than Win Thut is dismayed at the carnage caused by the military’s refusal to stop harassing and jailing doctors and let them tackle the pandemic as a public health issue.

“It’s sad. People are dying alone, collapsing in the street. Yet high ranking officers are taking oxygen and medicine for themselves and leaving lower rank soldiers to fend for themselves.

“The people have to manage the best they can, they can no longer expect anything from the government.”

Than Win Htut explains that reporting the health crisis is proving problematic.

“We cannot risk sending our reporters to confirm what’s happening at crematoriums or graveyards. Official sources won’t confirm or talk – they’re too scared.

“We keep in contact with our sources, but we can only manage to give estimates. State media can’t be relied on… nobody believes what it reports.”

The need for accurate reporting was never more important, he said.

“People are sceptical of vaccines, schools are closed, everywhere is overcrowded, there have been jail riots by anti-coup prisoners… unconfirmed killings of 20 jail protesters, doctors are being jailed, the cost of living is sky high, no work … no wages, medical supplies are being blocked… charity workers jailed.”

He says the pandemic has completely changed social media interactions.

“Facebook and social media sites have become our obituary pages. We see posts everyday of friends or their family members who have died. It’s tragic. We can’t do our job because the military has weaponised covid.”

Lost hope waiting on UN intervention

Wei Min Oo is still managing to work for a news agency and told IFJ he is lucky he still has a job.

“When the junta closed eight independent media outlets, hundreds of employed journalists were suddenly forced out of work. Journalists, like everyone, have to eat.

“Some journalists have opened online shops, young ones have become delivery riders and some can’t do anything, but try to live on their meagre savings.”

Trying to report when you can be arrested for just doing your job is one of the big difficulties.

“We can’t carry our journalist’s IDs. We have to make sure our phones are cleaned off as anything like Facebook that could get us in trouble at checkpoints. No bylines on stories. Journalists have to rely on social media as sources.”

Wei Min Oo said the massive number of covid-19 infections in the community means that reporters dare not go to areas under martial law or known crisis areas for fear of being arrested.

The actions of the military during the pandemic has exposed its disregard for civilians and community institutions critical to a democratic society, according to Wei Min Oo.

“The military is taking its revenge on doctors, health workers, teachers, students, politicians and charity volunteers for taking a stand by striking and speaking out.”

Meanwhile,people in Myanmar are scathing of international interventions happening and have resigned to opposing the military alone, he said.

“People now say ‘we have lost hope any international intervention will come — if we want a revolution we have to do it alone through our Civil Disobedience Movement’.”

There is no plan

Saw Win, a senior journalist who has worked in ethnic media for more than 20 years spoke to the IFJ about the greater effects the coup has had.

“The country is in chaos. The coup is a citizen’s nightmare. People have given up on international help. Working the borderline we see – displacement, refugees, corruption, armed conflict – any help will come with restrictions imposed on it by the military.

“Aid will eventually be allowed in and available, but it will not reach the people in need.”

Saw Win stresses the importance of accredited journalists being allowed to cover the pandemic.

“People don’t believe what they hear or see on state media. It’s total rubbish. Data, death rates, number of cases and health information are not believed. People joke the military run pictures and names of those they intend to arrest under 505(a) on state television and newspapers to get people to tune in – it’s the only item we can believe, the rest is useless.”

Covid’s impacts in the cities are worse than those experienced in rural areas, he says.

“We have pharmacies unable to buy or sell medicines, we hear of groups and individuals with links to the military profiting from selling oxygen cylinders, people can’t bury or cremate their loved ones, wet season floods, farmers not farming, food shortages, cooking oil prices have increased by as much as 33 per cent, essential shops are closing, refugee camps are struggling, there’s more than 200,000 displaced people in our region in desperate need of everything – these are all important stories our journalists need to keep covering.”

Phil Thornton is a journalist and senior adviser to the International Federation of Journalists in Southeast Asia.

Article by AsiaPacificReport.nz

![]()