Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Cameron Webb, Clinical Associate Professor and Principal Hospital Scientist, University of Sydney

Cameron Webb/NSW Health Pathology, Author provided

The extreme weather and flooding in recent days is likely to boost mosquito numbers, even as we say goodbye to summer.

Like all insects, mosquitoes thrive in warm conditions. Water is also critical for the mosquito’s life cycle, as they lay eggs in and around water. More water generally means more mosquitoes.

Disease caused by mosquito-borne viruses can be potentially severe. These include:

-

Ross River virus, which causes fever, chills, headache, muscle and joint pain and fatigue. It’s not fatal but it can be debilitating, and is the most commonly reported mosquito-borne disease in Australia

-

Barmah Forest virus is also common and causes fever, rash and sore joints

-

flaviviruses, including West Nile (Kunjin), Murray Valley encephalitis and Japanese encephalitis virus are extremely rare but can cause severe brain infection and death, in a small proportion of cases.

Health authorities will be closely monitoring flood-affected regions for these diseases.

While mosquito populations peak in summer, even without floods, these diseases generally peak in March and April. That’s because it takes time for the viruses to spread by mosquitoes among the local wildlife, such as water birds and native mammals, before spilling over into humans.

It’s too early to say what impact the floods will have on disease case numbers but it’s best to be prepared.

Read more:

La Niña will give us a wet summer. That’s great weather for mozzies

What happened after previous floods?

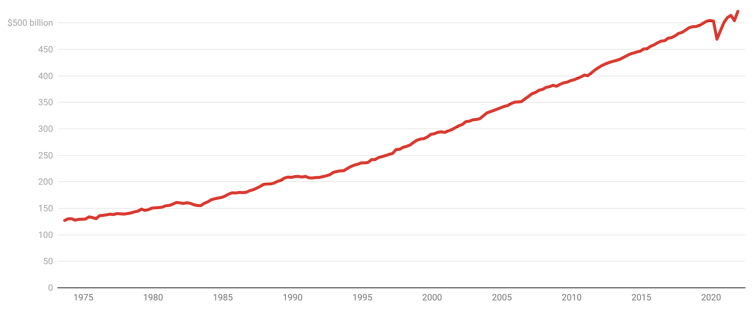

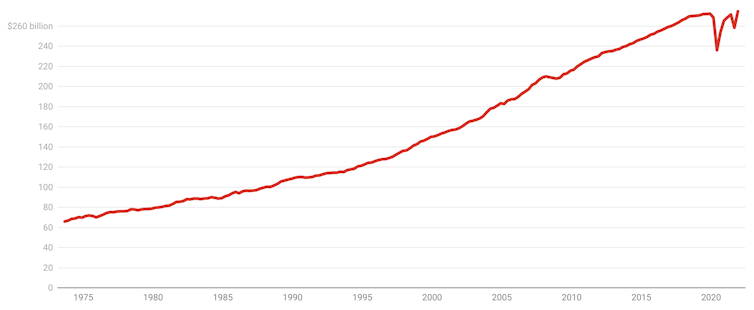

Major floods have triggered historically significant outbreaks of mosquito-borne disease in Australia.

Most notable was the outbreak of Murray Valley encephalitis virus in the 1970s. While authorities have been mindful of disease risk associated with flooding ever since, we’ve been spared a significant return of this virus.

Not so for Ross River virus.

In 2014-15, above average rainfall is thought to have provided habitat for freshwater mosquito populations that contributed to the major outbreak of Ross River virus in northern NSW and southeastern Queensland.

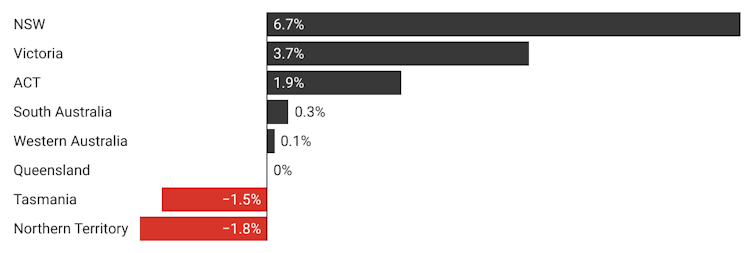

Flooding across Victoria over the 2016-2017 summer produced exceptional increases in mosquitoes. This resulted in the state’s largest outbreak of Ross River virus, with almost five times as many cases as the long-term average.

Following the exceptional rainfall that broke the East coast bushfire-swept summer of 2019-2020, NSW experienced its biggest outbreak of Ross River virus on record.

But more mosquitoes don’t always mean more disease.

Sometimes after floods, there is just too much water. It washes away any mosquito already present in the wetlands and displaces the animal hosts of viruses.

It may take some time for mosquitoes to move back in and build up their populations in the stagnant water left behind by the floods.

Read more:

Drinking water can be a dangerous cocktail for people in flood areas

What are health authorities on the look-out for?

Extreme weather events, such as the record-breaking floods we’re currently seeing, may cause more frequent and intense outbreaks of Ross River virus.

But it’s the potential to see the resurgence of more serious local mosquito-borne diseases – such as those caused by Murray Valley encephalitis virus – which has authorities most concerned because it causes more severe disease.

Read more:

Is climate change to blame for outbreaks of mosquito-borne disease?

The recent detection of Japanese encephalitis virus for the first time in southeastern Australia has shocked many, even those who have studied mosquito-borne diseases for decades. The discovery has health authorities on alert given the seriousness of the disease this virus causes.

While La Niña has played a role in new disease emergence, that may also quickly change. If a return to El Niño-dominated weather patterns brings back drought, that would see those wildlife and mosquito populations disappear.

Cameron Webb/NSW Health Pathology

‘Mozzie proof’ your property and family as floodwaters recede

Massive clean-ups will be required in coming weeks. That means long hours outside and much work done to make homes safe and secure again.

There isn’t much you can do to stop mozzies flying into your backyard from nearby flooded bushland and wetland areas.

Insecticide spraying may provide some relief but it is a short-term fix. As many commonly used products are not specific to mosquitoes, beneficial insects may also be killed if not used with caution.

Repairing, replacing, or installing insect screens on windows and doors can provide a physical barrier to mosquitoes seeking to fly inside your home.

Mosquito nets can also be a quickly deployed protection measure.

In your backyard, clean up as much debris as is safe to do so. Water-holding containers will quickly become a home to mosquitoes.

Gutters, drains and rainwater tanks can also be home to mosquitoes, so clean out and screen where possible.

Mosquito repellent may be your best friend over coming weeks. There is a range of formulations available from your supermarket, pharmacy or camping store. Choose a product that contains diethyltolumide, picaridin, or oil of lemon eucalyptus as these products will provide the best protection.

To get the most out of your repellent, ensure you have an even coat on all exposed areas of skin.

There are some alternatives to topical insect repellents, such as mosquito coils and other devices, but they can be limited in the protection provided.

Insecticide-treated clothing may also assist in beating the bites.

Read more:

Insect repellents work – but there are other ways to beat mosquitoes without getting sticky

![]()

Cameron Webb and the Department of Medical Entomology, NSW Health Pathology, have been engaged by a wide range of insect repellent and insecticide manufacturers to provide testing of products and provide expert advice on mosquito biology. Cameron has also received funding from local, state and federal agencies to undertake research into mosquito-borne disease surveillance and management.

– ref. How to mozzie-proof your property after a flood and cut your risk of mosquito-borne disease – https://theconversation.com/how-to-mozzie-proof-your-property-after-a-flood-and-cut-your-risk-of-mosquito-borne-disease-178299

.png?1646207862)

.png?1646207159)