Editor’s Note: Here below is a list of the main issues currently under discussion in New Zealand and links to media coverage.

Today’s content

Opening of new Parliament

Henry Cooke (Stuff): New Parliament brings old debates as Judith Collins and Jacinda Ardern fail to shift dial on first day back

Justin Giovannetti (Spinoff): Get set, go: Labour plans big sprint of new laws before Christmas

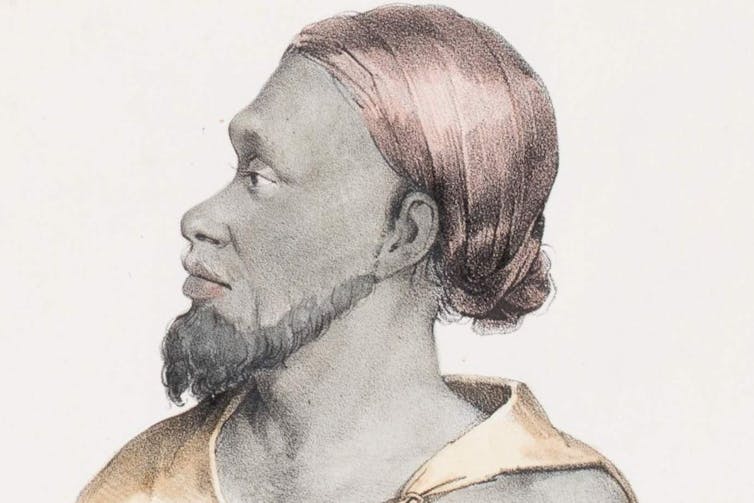

Henry Cooke (Stuff): New Zealand’s first African MP Ibrahim Omer recounts harrowing journey to Parliament as a refugee in maiden speech

Amelia Wade (Herald): How an East African refugee working 80 hours a week cleaning became an MP: Parliamentary maiden speeches begin

Jason Walls (Herald): Jacinda Ardern vs Judith Collins: 53rd Parliament kicks off in a blaze of fiery debate

Yvette McCullough (RNZ): Parliament opens to robust exchanges between govt and opposition

Herald: Judith Collins and Jacinda Ardern speak to MPs after State Opening of Parliament

1News: From refugee to MP: Labour’s Ibrahim Omer says he’ll fight for low-paid workers in maiden speech

Yvette McCullough (RNZ): Opening of Parliament – Governor-General’s Speech from the Throne

TVNZ: Following mum’s advice, Kelvin Davis spared NZ from his singing voice during Parliament waiata, he jokes

Herald: Is it time for Parliament to cut ties with wearing the tie?

RNZ: Should Parliament cut ties with ties? Shaw asks for rule change

1News: Speaker to consider dropping ties from Parliament’s dress code

Māori Party back in Parliament

Sam Sachdeva (Newsroom): Māori Party ensures Parliament returns with a bang

Joel Maxwell (Stuff): Māori Party storm out of Parliament’s first session, protest ‘tyranny of our democracy’

Jane Patterson (RNZ): Māori Party MPs walk out of Parliament in protest

Election and new Government

Peter Dunne (Newsroom): The tricky timing of constitutional change

Richard Harman: Shaking up the Nats

Chris Trotter: Spit & polish: A National Party story

Brent Edwards (NBR): Labour sets out its three-year agenda (paywalled)

Newstalk ZB: Jacinda Ardern ‘deeply grateful and humbled’ by rural support

Martyn Bradbury (Daily Blog): How dumb do the Greens feel now?

David Farrar: Poll on electoral changes

Chris Trotter (Daily Blog): The Second Term (With apologies to William Butler Yeats)

Housing

Matthew Hooton (Herald): Labour won’t let property bubble keep growing (paywalled)

Dan Satherley (Newshub): ‘Build like the Boomers did’: David Seymour says housing taxes ‘zero-sum thinking’

Herald: Editorial: Grant Robertson, the Reserve Bank and the housing crisis (paywalled)

Jenée Tibshraeny (Interest): Robertson: A bright-line test extension wouldn’t be a ‘new tax’

Jenée Tibshraeny (Interest): Orr refuses to be Robertson’s whipping boy

Brian Fallow (Herald): Spare us the finger-wagging over house prices, Grant Robertson (paywalled)

Liam Dann (Herald): Economy Hub: Adrian Orr on the politics of house prices and working with Grant Robertson (paywalled)

David Hargreaves (Interest): The Government, not the Reserve Bank, will have to tackle New Zealand’s many housing-related issues

Brent Edwards (NBR): Taking the politics out of the housing crisis (paywalled)

RNZ: Adrian Orr says Reserve Bank wants to introduce debt to income ratios to NZ

Newstalk ZB: New Zealand Initiative on the housing crisis and how it can be fixed

RNZ: Adrian Orr says Reserve Bank wants to introduce debt to income ratios to NZ

1News: Reserve Bank Governor not hopeful agency could help with housing affordability

1News: Chlöe Swarbrick, David Seymour spar over housing crisis, capital gains taxes

Newstalk ZB: David Seymour frustrated with government’s capital gains tax approach

Newstalk ZB: Will the Government keep its capital gains tax promise?

Zane Small (Newshub): Reserve Bank Governor to discuss tax changes in talks with Grant Robertson over house prices

Jenny Ruth (BusinessDesk): Kabuki dancing and the great Yes, Minister tradition (paywalled)

Michael Reddell: Robertson playing distraction

Michael Rehm (Newsroom): NZ’s housing debt dilemma

Rob Stock (Stuff): Reserve Bank raises spectre of wave of ‘managed sales’ of homes in March

Brent Melville (BusinessDesk): Home sellers racked up $4.4b in profits in Q3

Mark Quinlivan (Newshub): Rent costs up again in most regions ahead of summer

Vita Molyneux (Newshub): Dingy Wellington flat going for $815 per week – and people are queuing to pay

ODT: Housing waiting list continues to grow

Oranga Tamariki

Nicola Atwool (Newsroom): The collateral damage of ideologically-driven uplifts

Bonnie Sumner (Newsroom): Oranga Tamariki ‘all about agendas’

Jo Moir (RNZ): Kelvin Davis, Peeni Henare at odds over Oranga Tamariki comments

Joel Maxwell (Stuff): Defence Minister Peeni Henare forced on defensive in scrap with cousin, minister Kelvin Davis

Isaac Davidson (Herald): Kelvin Davis ‘disturbed’ by Oranga Tamariki’s removal of foster children

Sam Sachdeva and Melanie Reid (Newsroom): Kelvin Davis to Oranga Tamariki: please explain

Charlie Gates (Stuff): Oranga Tamariki emails details of suspected teen suicide to reporter

1News: Whānau Ora commissioning chair calls for Oranga Tamariki head to resign over failures towards Māori

Karl du Fresne: The Ferguson method

Martyn Bradbury (Daily Blog): New Oranga Tamariki footage will explode

Climate emergency

Heather du Plessis-Allan (Newstalk ZB): What is the point of declaring a climate emergency?

Henry Cooke (Stuff): Government to declare climate change emergency in Parliament next week

Jason Walls (Stuff): MPs will next week vote on whether or not Parliament should declare climate emergency

Anna Whyte (1News): Jacinda Ardern to declare climate emergency on behalf of New Zealand next week

Zane Small (Newshub): Jacinda Ardern to declare a climate change emergency in Parliament

Steven Cowan: Climate emergency declaration: Greenwashing the status quo

No Right Turn: Climate Change: An emergency

Martyn Bradbury (Daily Blog): Labour & Greens cleverly announce meaningless climate emergency to take heat off criticism from Left

David Farrar: Meaningless signalling

Border exemption for horticultural workers

Charlotte Cook (RNZ): Government’s seasonal workers move ‘not enough, but a good start’

Bonnie Flaws and Luke Malpass (Stuff): Government annouces first major border exemption with 2000 horticultural workers coming in the new year

Derek Cheng (Herald): Government to let in 2000 fruit pickers from Pacific – but with living wage catch

ODT: Public-private possible fruit-harvesting answer

Esther Taunton (Stuff): Pacific workers to pick fruit in NSW while NZ Govt ‘picks fight with farmers’

Mike Hosking (Newstalk ZB): If Govt wants to fix the skills shortage, they need to let people in

Economy and work

Marta Steeman (Stuff): Critics urge Ryman Healthcare to repay the $14.2m wage subsidy

Anuja Nadkarni (Stuff): Media company Stuff to trial unlimited sick leave for staff

Alexia Russell (Newsroom): Tourism’s Covid reset

Jamie Gray (Herald): Continuous Disclosure: What happens to markets, post Covid? (paywalled)

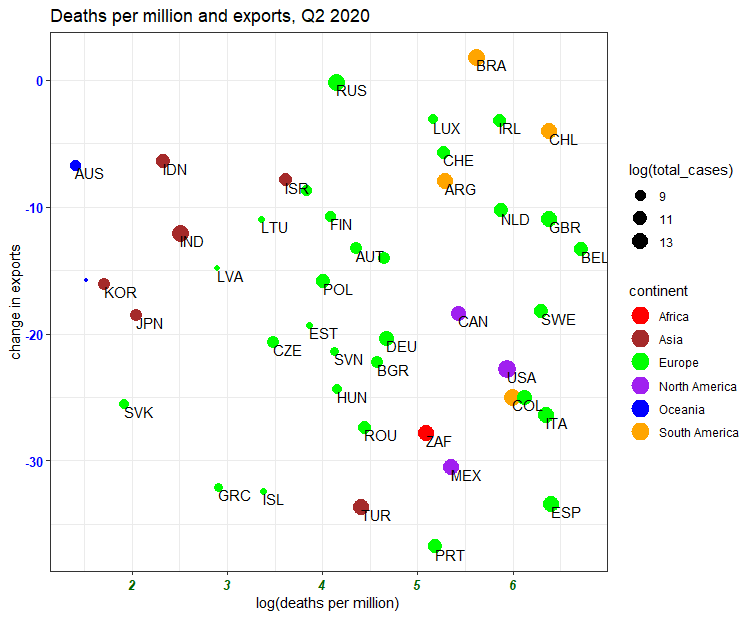

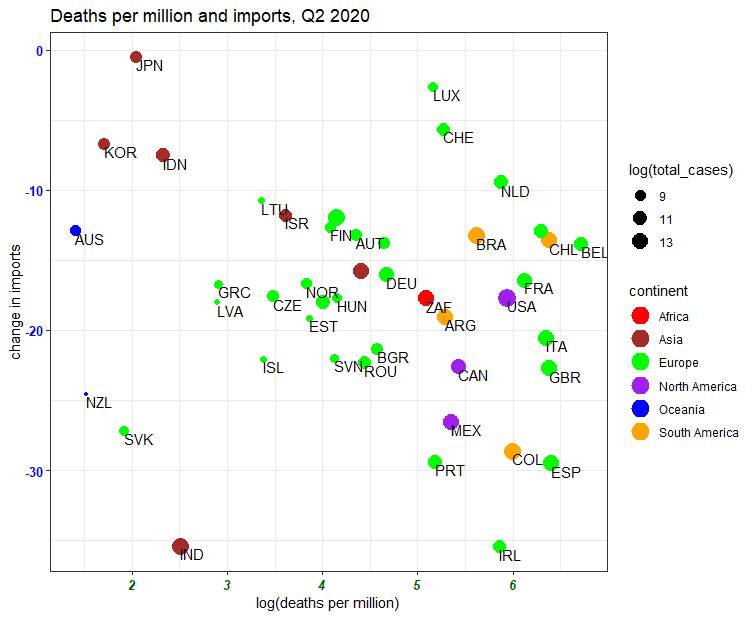

RNZ: New Zealand records biggest annual trade surplus in 28 years as imports drop

Andy Fyers (Business Desk): A big tax boost for Government coffers (paywalled)

Brent Edwards (NBR): National challenges the government over rising public debt (paywalled)

Covid

Jason Walls (Herald): Covid-19 coronavirus: Kiwis to get free access to vaccine, Governor-General confirms in Speech from the Throne (paywalled)

Anna Whyte (1News): Covid-19 vaccine to be free as soon as ‘available and safe’, Governor-General says on behalf of Ardern

Henry Cooke (Stuff): Coronavirus: Government confirms Covid-19 vaccine will be free in speech setting out goals for next three years

Mike Hosking (Newstalk ZB): Government must crack on with Covid vaccine delivery

Julia Gabel (Herald): Covid 19 coronavirus: Second cricket team caught out by CCTV as players test positive

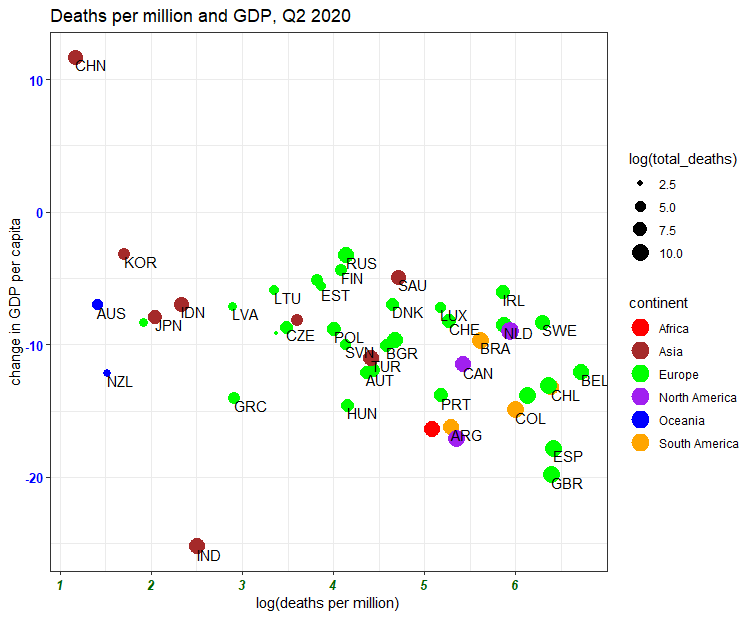

David Farrar: NZ has lowest Covid-19 death rate in OECD

Benn Bathgate (Stuff): Coronavirus: Women still leading the pack in Covid card trial

Royal Commission into terrorist attack on Christchurch mosques

Stuff: Editorial – We must always be vigilant about the terror threat

Steven Walton (Stuff): Mosque shooter’s interview with royal commission won’t be released to the public

Herald: Royal Commission’s findings on Christchurch mosque attacks handed to government

Katie Scotcher (RNZ): Royal Commission into terrorist attack on Christchurch mosques finally handing over report

Ella Prendergast, Miriam Harris and Mark Quinlivan (Newshub): Christchurch mosque attack: Islamic Women’s Council says Royal Commission report must be released this year

Government’s light rail project

Bernard Orsman (Herald): Auditor-General finds fault with Government’s handling of Auckland light rail

Thomas Coughlan (Stuff): Auditor-General warns Government he’ll be watching light rail closely after ‘unusual’ process

Brent Melville (BusinessDesk): Watchdog raises red flag on $6b light rail ‘process’ (paywalled)

Local government

Rosemary McLeod (Stuff): I’m searching in vain for a sense of outrage over Wellington Mayor Andy Foster

Kate Hawkesby (Newstalk ZB): What Tim Shadbolt has in common with Donald Trump

Mike Mather (Stuff): City council’s assumptions exercise ‘just meaningless box-ticking’

Mandy Te (Stuff): Housing woes can’t be addressed by creating ‘Stalinist, gothic monstrosities’ in Wellington’s Khandallah

International relations and trade

Sam Sachdeva (Newsroom): What the ‘Biden doctrine’ may mean for the world

John Weeks (Herald): Chinese spy sent to NZ to track Taiwanese migrants and then abandoned the mission has visa bid appeal dismissed

Newstalk ZB: Foreign Affairs Minister: No backlash from China over Five Eyes statement

Health

Rowan Quinn (RNZ): Lack of specialists adds to burnout and long waiting lists, research shows

Natalie Akoorie (RNZ): Inequity in cancer care at every turn for Māori

Kristin Hall (1News): Period poverty campaigners disappointed by delay to Government’s rollout of free products for students

Murphy and Susan Strongman (RNZ): High costs, long waits: Trans healthcare barriers across NZ remain

Education

RNZ: Principals struggle with meeting needs, despite teacher aides pay deal

Georgina Campbell (Herald): Wellington High School lockdown: Police speaking with two young people

Sophie Cornish, Tom Hunt and Laura Wiltshire (Stuff): Wellington High School locked down after ‘credible threat’ of attack

Other

Benn Bathgate (Stuff): Salvation Army report reveals decade-high benefit numbers and fears for the ‘Covid Christmas’

RNZ: Salvation Army report finds social needs increasing in all areas

Chlöe Swarbrick (Stuff): Drug law reform is staying on the political agenda

RNZ: More than half of New Zealand lakes surveyed ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’

Simon Wilson (Herald): The good and bad news about boomers (paywalled)

Laura Walters (Newsroom): A dispassionate response to emotive crimes

No Right Turn: NZDF should not be allowed to handle this in-house

Martyn Bradbury (Daily Blog): Espionage arrest secondary to holding SIS & GCSB to account for Australian white supremacy terrorist

Marty Sharpe (Stuff): Disagreement means hapū and iwi will not be on trust to run Te Mata peak park

Joseph Mooney (Stuff): Seeking sensible fixes for freshwater rules, staff shortages

Michael Neilson (Herald): Abuse in Care: Catholic Church loses bid to keep names of abusers secret

Andrew Macfarlane (1News): Nearly a third of all ‘serious’ cyber-attacks in NZ targeted public sector, report finds

Herald: NZ Herald audience breaks records in extraordinary news year

Nicola Short (Newsroom): Little regard for Māori heritage

Newstalk ZB/Herald: We’ll discuss it’: Black Caps consider kneeling prior to first T20