Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By David Smerdon, Assistant Professor, School of Economics, The University of Queensland

The new Netflix miniseries The Queen’s Gambit has received rave reviews around the world. Surprisingly for a chess-themed show, it received a warm reception by the global chess community, which is usually highly critical of portrayals of tournament chess in film.

The experiences of star character Beth Harmon loosely correlate to those of Bobby Fischer, a US chess prodigy and arguably the most talented player in history. Fischer rose to fame in the 1950s, becoming the youngest ever US Champion at age 14 and breaking the record for the youngest international grandmaster one year later.

His meteoric rise ignited an explosion of popularity in the Western world for the historically Soviet-dominated game. Fischer’s victory in the World Chess Championship in 1972 against the Russian-born Boris Spassky came in the midst of the Cold War and captured the attention of the general population around the world.

This famous match is emulated in the final episode of The Queen’s Gambit, in which the American Harmon plays her own Soviet nemesis in Russia.

But chess in Australia during the 1960s, the period of The Queen’s Gambit, was a far cry from the popularity of the game in the US.

Read more: Checkmate: top chess players live longer

Chess in Australia in the 1950s and ‘60s

Australia had no recognised chess grandmasters at the time. Its geographic isolation presented logistical and financial obstacles to chess improvement.

It proved almost prohibitively difficult for Australian players to acquire chess learning materials and travel abroad to tournaments.

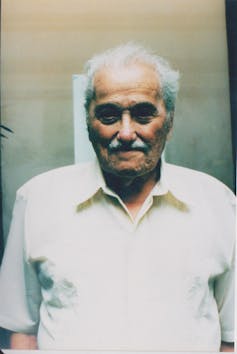

The chess scene was largely dominated by two men, Gary Koshnitsky and Cecil Purdy. Koshnitsky was born in Kishinev, in what’s now Moldova but was then part of the Russian Empire. He emigrated to Australia as a child, where he went on to become Australian champion.

Purdy was born in Egypt but his family eventually moved to Australia, and he taught himself chess as a teen. He won the inaugural World Correspondence Chess Championship, in which individual moves were sent and received by post in the early 1950s, and earned titles of international chess master and international grandmaster of correspondence play during the same decade. (He collapsed while playing a chess tournament in 1979 and died that day. Reportedly, his last words were about his final game: “I have a win, but it will take some time.”)

Purdy and Koshnitsky wrote a book titled Chess Made Easy. It was hugely popular worldwide, selling 600,000 copies in Australia alone.

Australia’s first grandmasters

Things started to pick up in the 1970s and ’80s, primarily in Melbourne, where the third-largest chess library in the world, the MV Anderson Collection at the State Library of Victoria, was hosted. It was, and still is, enormously helpful as a place for chess players to acquire knowledge and meet other players.

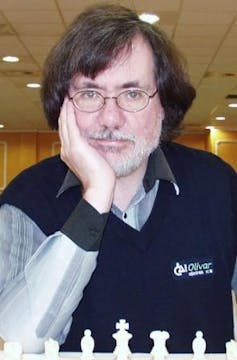

The Melbourne chess scene helped develop Australia’s first two chess grandmasters, Ian Rogers and Darryl Johansen.

The title of grandmaster is awarded by the world chess federation (also known as Fédération Internationale des Échecs or FIDE). To earn it, a player must achieve three grandmaster “norms” (based on an outstanding performance in an international chess tournament), each of which typically requires beating several players of master level in a single event.

For Rogers and Johansen, this meant living out of suitcases in Europe for periods of the 1980s and giving up the option of a regular job and steady income to pursue their chess careers.

Their sacrifices blazed a trail for other Australian chess players to follow. There was substantial growth in the chess community and particularly in the development of the junior ranks during the 1990s.

Another significant factor was the introduction of “chess in schools” businesses in the late 1990s. Coupled with the formation of a national competition for schools, this led to a dramatic increase in the number of Australian children learning chess, a trend that continues today.

A tipping point for Australian chess

Despite these developments, it was still some time before an Australian player was again able to break into the grandmaster ranks.

When one of us (David Smerdon) achieved a grandmaster norm in 2006, it ended a drought of 25 years.

This coincided with a tipping point for Australian chess. By 2009, the number of Australian grandmasters had doubled from two to four, and by 2020 it had risen to ten.

In recent years, a number of individual and team achievements paint a promising picture for the future. At the 2016 chess Olympiad in Azerbaijan, an Australian earned a draw against the reigning World Champion for the first time.

And in October this year, the Australian team sensationally won the Asian Nations Cup, beating top seed India (ranked fourth in the world) in the final.

The championship was held online due to COVID restrictions; chess has been one of the few sports largely unscathed by the pandemic, and in fact has significantly increased its membership during 2020.

Queens and Kings

The steep increase in popularity of internet chess has helped level the playing field for traditionally less prominent chess nations in Australia, Asia and Africa.

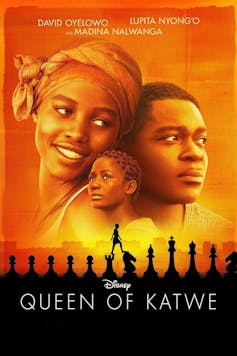

This is personified in another success of chess on the screen: the 2016 film Queen of Katwe. It tells the true story of a 10 year old Ugandan girl, Phiona Mutesi, who learned chess in the slums of Kampala. Mutesi would eventually go on to represent her country at the 2010 chess Olympiad in Siberia, and has proved an inspiration for chess-playing girls in Uganda and other African nations.

Not all the elements in The Queen’s Gambit reflect reality. No female player worldwide has ever contested the chess World Championship, and only one has been ranked in the world’s top ten.

Men dominate participation rates as well: only 15% of the players with international chess ratings are female.

Many hope the unexpected success of the Netflix series may spark a boom for women’s chess not unlike Fischer’s impact on chess in the West.

Though women’s chess in Australia is still waiting for its own tipping point, there are promising signs. In 2017, a Queensland woman, Heather Richards, achieved the first victory by an Australian female over a grandmaster since the turn of the century (unfortunately, the victim was one of us – David Smerdon).

Hopefully, it is only a matter of time before we see the emergence of our own Australian Beth Harmon or our own Queen of Queensland.

Read more: Most people think playing chess makes you ‘smarter’, but the evidence isn’t clear on that

– ref. The Queens(land) gambit: a brief history of chess in Australia – https://theconversation.com/the-queens-land-gambit-a-brief-history-of-chess-in-australia-150638