Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Matt Harvey, Senior Lecturer in Law, Victoria University

Earlier this month, the Federal Court found the Gillard’s governmnet’s controversial 2011 live export ban was unlawful.

But this is not a problem for the former government, who imposed the ban. It is one the current Morrison government has to grapple with.

Not only do they face millions of dollars in damages, but the Federal Court judgment raises serious questions about the limits of ministerial decision-making.

How did this start?

In June 2011, then agriculture minister Joe Ludwig issued a snap, blanket ban on Australia’s live cattle exports to Indonesia for six months.

Read more: Can meat exports be made humane? Here are three key strategies

This followed a Four Corners report featuring disturbing footage of the treatment of Australian cattle at Indonesian abattoirs.

At the time the footage aired, the minister was already in discussion with exporters about the conditions in abattoirs. Several “closed loops” had been created in which the entire journey of an animal from Australia to the abattoir in Indonesia had been subjected to quality control.

But the footage was so shocking, there was public pressure to do more.

Ludwig issued orders under the Export Control Act to suspend live cattle exports to Indonesia, without exceptions.

While the ban was celebrated by animal welfare groups, it angered the live cattle industry. It caused great difficulties for exporters in the process of shipping stock and they suffered significant losses and additional costs.

In 2014, the Northern Territory-based Brett Cattle Company launched a class action against the agriculture minister and the Commonwealth.

What did the Federal Court find?

The Federal Court handed down its landmark ruling on June 2.

Justice Stephen Rares found the ban was “capricious and unreasonable”, and Ludwig had committed the “tort of misfeasance” in public office by imposing the live export ban without regard to its possible illegality and the losses it would cause.

This means Ludwig either knew the ban was beyond his ministerial power, or was reckless as to whether it was. There was also recklessness regarding the possible harm that might result.

The key element here is the lack of an honest attempt to perform the functions of the ministerial office, with “honest” having the technical legal meaning of genuine belief that your action is lawful.

Rares wrote Ludwig “plunged ahead” with the ban, even though

he knew that he had no advice about whether it would be valid and that there was a real risk that it would not be.

What does this mean?

This means damages will be awarded to the plaintiffs in the class action, unless the former minister or the Commonwealth successfully appeal.

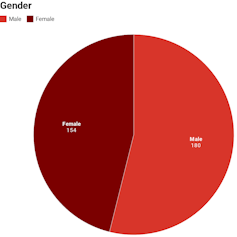

To date, 300 parties have joined the class action, calling for a reported $600m in compensation.

Apart from the price tag, the case is also potentially significant as a major restraint on ministerial discretion.

Read more: The ban on live sheep exports has just been lifted. Here’s what’s changed

While there have been other bans of particular forms of live exports since this one in 2011, ministers now know that they cannot simply impose a blanket ban, but must take legal advice and proceed with caution.

What happens now?

Having made his findings, Rares has now invited the parties to confer on how damages and costs will be calculated.

Ludwig seems unlikely to appeal. He did not give evidence in the case. While he may face personal liability, the Commonwealth is also liable.

The Morrison government is currently weighing up an appeal. The prime minister reportedly told a meeting of Coalition MPs earlier this month the judgement raised “real issues”.

Earlier this week, Attorney-General Christian Porter said he was still deciding about a possible appeal.

“I take a very cautious approach,” he told reporters in Canberra. “And what I want to understand is what are the potential implications of that decision for a range of industries, including the live animal export industry?”

Even though the current government is highly critical of the 2011 decision, no government would wish to have ministerial discretion restrained in this way.

Appealing is costly, but the Commonwealth has deep pockets.

Their preferred course at this stage, though, may be to reach agreement on damages and costs, rather than leaving these to the court. Porter says he won’t make a decision on an appeal until June 29, when final orders are delivered on the case.

What are the chances of a successful appeal?

An appeal would have to argue the judge made an error of law.

The judgment has been very carefully crafted and may well withstand appeal, but the principles at stake are worth testing.

As Porter reportedly told colleagues, the tort of misfeasance has been applied here in a way not seen before.

Read more: The ban on live sheep exports has just been lifted. Here’s what’s changed

Regardless of whether an appeal is pursued, ministers are more likely to take more advice before acting in future.

However, nine years after the event, it is hard to see this as an effective form of ministerial accountability. The affected exporters look likely to finally get some compensation. But the cattle are long dead.

– ref. How the Gillard government’s live cattle ban created a headache for Scott Morrison – https://theconversation.com/how-the-gillard-governments-live-cattle-ban-created-a-headache-for-scott-morrison-140551